Last updated: October 23, 2022

Article

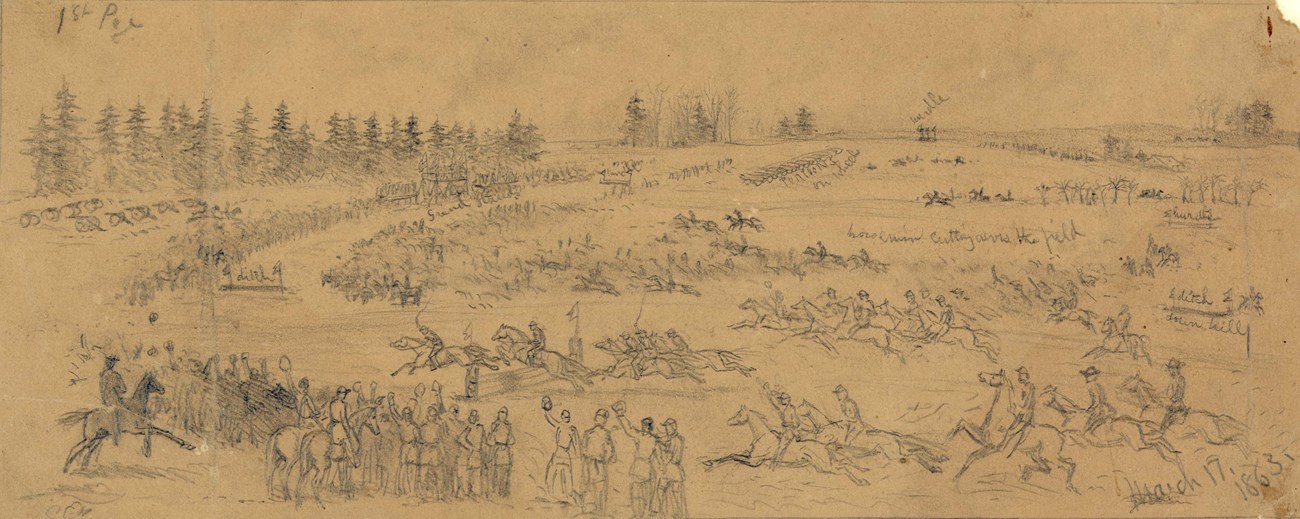

St. Patrick's Day with the Irish Brigade

Grand Irish Brigade Steeple-Chase,

To come off the 17th March, rain or shine, by horses, the property of, and to be ridden by, commissioned officers of that Brigade. The prizes are a purse of $500; second horse to save his stakes; two and a half mile heat, best two in three, over four hurdles four and a half feet high, and five ditch fences, including two artificial rivers fifteen feet wide and six deep; hurdles to be made of forest pine, and braced with hoops.1

Sketch by Edwin Forbes, Library of Congress

The day began with religious ceremonies in the morning, and while there were a variety of games planned and plenty of punch to go around, the crowning event was the grand steeplechase. The steeplechase was a wild, dangerous affair that drew more than 10,000 spectators from all parts of the army. It is not known precisely where the great race took place, but it was likely somewhere north of what is today Exit 133 on I-95, the junction with Route 17.

What follows is a description by Samuel S. Partridge of the 13th New York, who witnessed and then joined the race. Partridge was a superb letter writer, conveying vivid details and sharp observations. This is one of the best descriptions of the steeplechase in March of 1863.2

To night I am going to tell you about the great steeple chase in the Irish Brigade on St. Patricks day.

It beat Donnybrook fair all to the mischief. A race course—elliptical—of a mile was laid out. Guidons and such things were stuck in the ground to point out the course to the riders. There were four hurdles and three ditches…There were more than 20,000 spectators, soldiers and officers. Everybody who could get a pass from camp was there, some even walking a dozen miles through the mud to get there. The track was slippery blue clay and about half hoof deep.

The hurdles were made of logs forty feet long, laid three side by side, three logs high, and hurdle no. 2 four logs high. A horse stumbling on a fence may knock a rail off and get not fall, but here, when a horse stumbled “somebody got hurted” every time. No. 3, the twelve foot ditch, was in a little valley, the ground sloped towards it each way. It was as deep as it was wide, and so slippery was the bank, that if a horse paused a tenth of a second to measure his distance, he slid in. None but horses who took this hump on the swing got over, and a good many of these fell short. I went over this while four horses and riders were wallowing in the mid. No. 5, the eight foot ditch, had on the far side a hedge two feet high made of stakes driven in to the ground and cedar boughs interwoven, that stuck many a horse and hurt many a rider. No. 7, six foot ditch, on the home stretch, had hard gravelly banks, but you were doing up hill when you came at it.

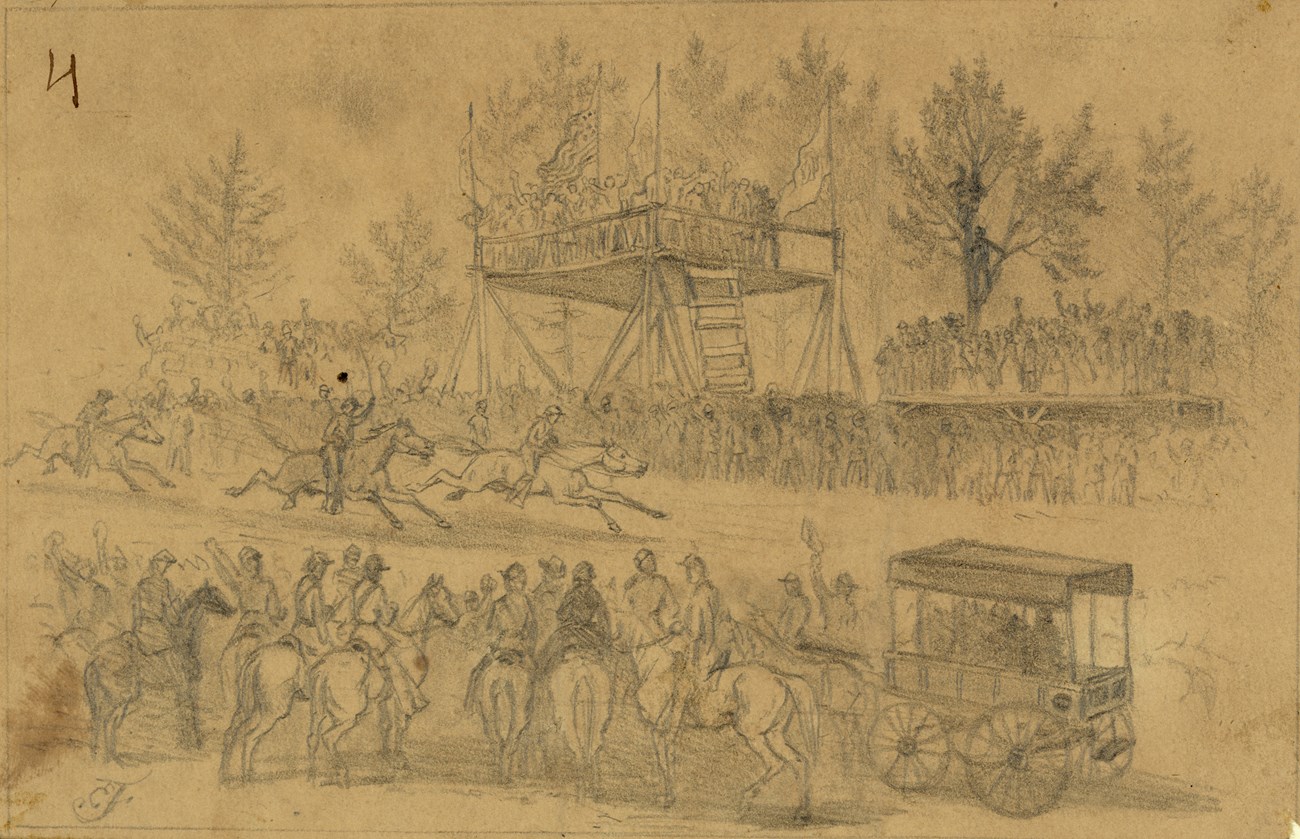

For the Steeple Chase of two heats only eight or ten horses were entered, all of Meaghers Brigade. Major Genl. Hooker was the umpire.

One rider was clad in white curdoroys, wax top boots, drab cutaway coat and drab stovepipe hat, regular English jockey style. One Greek Captain had a silk goat, one side green with white sleeve, the other side white with green sleeve. His horse bolted the first hurdle and pitched him over it, but he arose with his many colored coat all slate color, remounted and made him take the leap. The horse also went over the twelve foot ditch and left the rider in it, and I saw neither horse nor rider again.

Both heats were won by a chestnut stallion with a white mane and tail, ridden by a boy, an officer’s servant, about fifteen years old, and not over ninety weight.

The second heat being over, Col. Schoeffel proposed to me to go over that hurdle, pointing to the highest. As he is a large sized man, I didn’t think he would dare follow me, but was rather daring me to do it. So I never said a word but laughed at him and rode Black Dan over the hurdle, and looked back just in time to see Schoeffel come flying after me on his Frank, a big blood bay, and just for the fun of the thing we kept on round the course. The way we scattered the men off that track was a caution, and the way the crowds at the ditches and hurdles would yell when we got to them was enough to scare a horse over an eight rail fence.

Sketch by Edwin Forbes, Library of Congress

Then came a race just for fun, free to all officers horses—horses to be placed with their tails on the score, and at the word go to whirl round and run in the opposite direction. Lots of small, light weight men wanted to ride Frank. The Colonel’s large bones are too heavy for that horse. I rather wanted to find somebody to ride Black Dan, for if you don’t give him a free hand, he has a way of pitching the rider and going over the track alone. In our camp scrub races Hall rides him bare back and with a halter only, putting the strip in his mouth.

One of my teamsters who was riding him to water undertook to run him once without my knowing it. He gut run away with and thrown off and was over two hours catching the horse again. But as I haven’t been thrown yet, I went it myself.

At the word go! Ten or a dozen horses started straight off and went ten or twenty rods before the riders could turn them. Those of us who know how, executed a “demi-volt” and let em spin. If a horse bolts at a jump, or goes round it, he is out of the race, unless he goes back and takes it again. It is ruleable for a horse to go over everything—no matter how—so he goes over. If he misses he is distanced.

I never rode so fast before. It took all the horsemanship I know to do it. I kept a tight rein, till within three lengths of the jump, and then loosened up by holding the bridle hand forward about half way up the back, so as to tighten up after the jump by drawing the hand back again, without loosening the reins and gathering them up again. I remembered too to sit close to the saddle as I ran, and to raise the body from the saddle on the jump, but keep the knees close as though there was a pivot through them.

There were five beside Schoeffel and myself went everything clear. The rest except the few who got stuck came straggling in afterwards.

Your fancy riders, who have the stirrups so long that they have to point the toe down to reach it, did very well when their horses rose to the first leap, but when they came down they saw their stirrups flying about their ears, and the jolt of it didn’t unhorse them so shocked their sense of propriety that they didn’t do so any more. Your men with their feet all gathered up in very short stirrups found themselves shot over their horses head like a hot shot out of a scoop. And the foo foo’s who took hold of the pommel of the saddle with the right hand generally got jerked on to the beasts neck.

It was the biggest spree I ever went on—the wildest ride I ever took—and I don’t want to do so any more. Col. Schoeffel’s Frank was as still this morning as a wooden horse and Black Dan felt a little old, if I could judge by the way he went under the saddle this afternoon. I feel proud of my horse, and al little vain of my horsemanship, but at the next Steeple Chase count me a spectator. As a rider “Excoosy me.” I’d rather look on and see bones broken than risk my neck in any way not in the Army “regulations.”

Sketch by Edwin Forbes, Library of Congress

The Irish Brigade was established to advance the interests and reputation of the Irish in America. It was a way for Irish immigrants to claim rights as American citizens, and for the Union to galvanize support from the Irish for the war. In December, the Battle of Fredericksburg drastically reduced the brigade's numbers, as had the Battle of Antietam a few months before that. Brigadier General Thomas Francis Meagher spent the winter unsuccessfully advocating for his regiments to be granted leave to recruit more soldiers.

A little more than a month after St. Patrick's Day, the Irish Brigade was again in action at the Battle of Chancellorsville. The Irish Brigade, once over 2,000 strong, would exit the Battle of Chancellorsville and march up to Gettysburg with just a few hundred soldiers.

Sources:

1. David Power Conyngham, The Irish Brigade and Its Campaigns: With Some Account of the Corcoran Legion, and Sketches of the Principal Officers (New York: W. McSorley & Company, 1867), 372.2. Samuel S. Partridge, Letter of March 18, 1863, Private collection of Mrs. J.H. King. Transcript of original letter at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park.

Further Reading:

Macnamara, M.H. The Irish Ninth: In Bivouac and Battle, or Virginia and Maryland Campaigns. Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1867.