Part of a series of articles titled French Language and the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Article

Ste. Genevieve and the Lewis and Clark Expedition

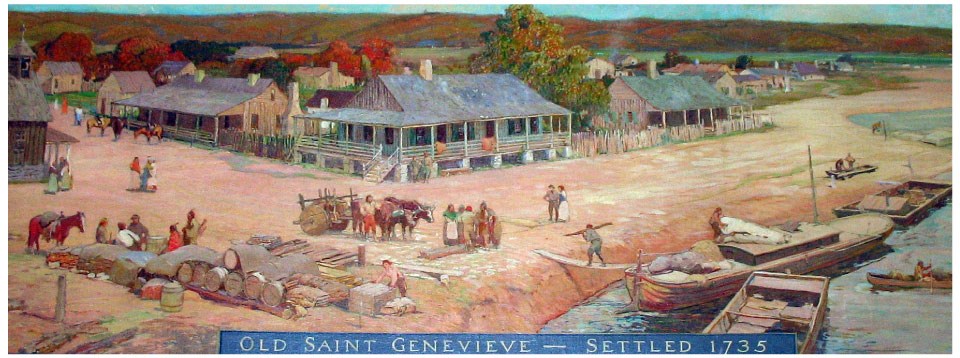

Oscar E. Berninghous.

This article is one in a series, French Language and the Lewis and Clark Expedition, by Lewis and Clark Trail Digital Interns.

Author: Andrew Fournier

Ste. Genevieve was named for the patron saint of Paris, who lived during the 5th century AD. Interestingly, in the 17th and 18th centuries, around the time that explorers were settling the area, Sainte Genevieve figured largely in the minds of the French. Houck (1908) noted that all the French settlers were strict and exemplary Catholics (277).

Sainte Genevieve was born around 422, and she is commemorated on January 3 within the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches. According to her narrative, Sainte Genevieve was known for her generosity to the poor. She gave so much that when she passed the age of 50, her bishops commanded her to add fish and milk to her diet. On more than one occasion, candles were known to light spontaneously in her hand, which is why many icons represent Sainte Genevieve as holding a candle. In 451, due to the approaching armies of Attila the Hun, Sainte Genevieve led the women of Paris in prayer and fasting. Attila the Hun instead moved to Orleans, where they were defeated. Consequently, she is the patron saint of Paris. Sainte Genevieve died in 512 at the age of 80.

Image Use Courtesy of The Orthodox Church in America

An effective cult had developed around the saint in Paris. Williams noted 120 processions of the saint’s relics in Paris between 1500 and 1793 (Williams, 339). There were three prominent processions in 1694 (after a drought that was met with rain immediately after the procession), 1725 (to stop the rain which continued; Williams, 332), and 1744 (to cure the King of smallpox which was cured three days later; Williams, 340). Revolutionaries in France destroyed the relics of Sainte Genevieve on December 3, 1793 (Williams, 349) as one of the manifestations of the French revolution.

Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet were the first explorers in the early summer of 1673 to visit what would become the site of Old Ste. Genevieve. First named Old Town (Mueller), later Frenchmen would establish the town about 75 years later (Ekberg, 44) around 1750, if not a few years earlier (Ekberg, 47). As of 1752, the total population was 23 (Recensement general du pays des Ilinois de 1752). Old Ste. Genevieve was the earliest permanent European settlement west of the Mississippi in Upper Louisiana (Ekberg, 45). Old Ste. Genevieve was peaceful in its first decade of existence, untouched by the French and Indian wars and left alone by the Osage Indians (Ekberg, 47). Not long after the flood of 1785, Ste. Genevieve moved to higher ground. In a letter to James Madison dated September 29, 1803, Clark wrote that at Ste. Genevieve there were about 30 Peoria and Illinois Indians. The Peoria and Illinois Indians refrained from hunting out of fear of encountering other Indians. They were the remnants of what numbered 1200 warriors 50 years previous (Carter).

The De Laurier family also figured prominently in Ste. Genevieve (Houck, 1908, p. 90). One of the De Laurier family in particular, Henry De Laurier, may have been one of the individuals mentioned as Mr. Henry Delorn in Clark’s September 6, 1806 entry (Moulton, 352). One resident of the town was paid by the expedition. Charles Gregoire, from Ste. Genevieve, was paid $1500 on March 28, 1804 (Lewis). However, since the note may about Gregoire was possibly a later addition, Gregoire may not have been in Ste. Genevieve at the time. Clark dined with Francois Duquette, a former resident of Ste. Genevieve, in Ste. Charles on May 16, 1804 (Clark). Jean Vallé was also from Ste. Genevieve (October 1, 1804).

Son of Francois Vallé, Jean Baptiste and his wife Marie-Jeanne moved in with Francois (home built in 1785) to care for his father just prior to his death in 1783. Francois had made a fortune through mining and trading during his time, and his estate was divided among his descendants. Researchers speculate that Jean’s mother passed in 1781 possibly due to a yellow fever epidemic as there was an outbreak that had passed through Ste. Genevieve (Barnett). According to Clark’s journal for November 28, 1803, the expedition arrived at a landing on the other side of St. Genevie [sic] (Clark). By the time of the expedition, the population of New Ste. Genevieve was around 1000. About one week later, Clark gave further descriptions of the town. He wrote that the town was primarily French with about 120 families. North and South Gabourie creeks, which ran north and south of Ste. Genevieve, were likely named for an early French settler and stone mason (Mueller), Laurent Gabourie. There was evidently a Kickapoo village near Ste. Genevieve (Houck, 362). Some argue that Clark’s reference to sending Lorimer to Kickapoo Town may refer to Shawnee. The Shawnee and Delawares were in around Ste. Genevieve, having been pushed west by pressure from other tribes and the American westward movement. There was a big Shawnee village on Apple Creek (Ste. Genevieve district’s southern border with Cape Girardeau district). Lorimer was the head of the Cape Girardeau, and his wife was Shawnee. Both the Shawnee and Kickapoo were allies and shared a similar language. The Kickapoos were an enemy of the Osage who had populated most of Missouri south of the Missouri River. The Kickapoo Indians turned to be a strong American ally. Lewis later wrote that he had spoken to the Kickapoo (Mueller). Lewis informed them that their enemy, the Osage Indians, were no longer under the protection of the United States, and that the Kickapoo were free to deal with them as they saw fit (Gibson, 97). According to Clark’s survey of Indians, there were Peoria and Illinois Indians near Ste. Genevieve (Clark).

Ste. Genevieve was among several towns considered to be the capital after Missourians voted for their first state officials in August 1820 (Ohman, 10). When plans were being made in 1913-1914 for a rebuilt capital building in Jefferson City, John Gill and Sons attempted to use Ste. Genevieve as the site for the quarry to mine the stone. A quarry at Ste. Genevieve would have saved the construction effort $137,000. However, the board governing construction insisted in mining the stone from Carthage, on the western side of Missouri (Ohman, 77).

References

Barnett, Todd. "François Vallé - SHSMO Historic Missourians." SHSMO Historic Missourians, historicmissourians.shsmo.org/francois-valle. Accessed 29 Oct. 2021.

Carter, Clarence, editor. The Territorial Papers of the United States, 1854-1872. Washington, D.C., National Archives.

Clark, William. “December 4, 1803 Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.” Lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu, https://lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.jrn.1803-12-04#lc.jrn.1803-12-04.01. Accessed 13 Oct. 2021.

Clark, William. “May 16, 1804 Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.” Lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu, lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.jrn.1804-05-16#lc.jrn.1804-05-16.01. Accessed 13 Oct. 2021.

Clark, William. “November 28, 1803 Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.” Lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu, lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.jrn.1803-11-28#lc.jrn.1803-11-28.02. Accessed 13 Oct. 2021.

Clark, William. “October 2, 1804 Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.” Lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu, https://lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.jrn.1804-10-02#lc.jrn.1804-10-02.02. Accessed 28 Oct. 2021.

Clark, William. “Part 2: Estimate of the Eastern Indians Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.” Lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu, lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.jrn.1804-1805.winter.part2#lc.jrn.1804-1805.winter.part1.01. Accessed 13 Oct. 2021.

Ekberg, Carl J. François Vallé and his World: Upper Louisiana before Lewis and Clark. University of Missouri Press, 2002.

Gibson, Arrell Morgan. The Kickapoos: Lords of the Middle Border. Norman Okla., University of Oklahoma Press, 2006.

Lewis, Meriwether. “Various Dates, December 4, 1803-March 29, 1804 Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.” Lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu, lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc. jrn.1804-03-29-1#lc.jrn.1804-03-29-1.01. Accessed 13 Oct. 2021.

Houck, Louis. A History of Missouri: Volume I. Ville Platte, La., Provincial Press, 2001.

Houck, Louis, A History of Missouri: Volume II. Chicago, Il., R. R. Donnelley & Sons Company, 1908.

Mueller, Robert. Interview. By Andrew Fournier, December 14, 2021.

Moulton, Gary E.. The Definitive Journals of Lewis & Clark: From the Ohio to the Vermillion. United States, University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

“October 1, 1804 Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.” Lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu, lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.jrn.1804-10-01#lc.jrn.1804-10-01.01. Accessed 13 Oct. 2021.

Ohman, Marian M. "The history of Missouri capitols." (1982).

"Quel est le bâtiment le plus ancien de votre état? - Cartes Étranges Novembre 2021." Un Grand Penseur, fr.gov-civ-guarda.pt/how-young-is-oldest-building-your-state. Accessed 1 Nov. 2021.

“Recensement général du pays des Ilinois de 1752”. Reference Huntington Museum, Loudon Papers, Vaudreuil subsection, call No. LO426. S1.Sos.mo.gov, s1.sos.mo.gov/CMSImages /MDH/1752.pdf. Accessed 22 Oct. 2021.

“September 6, 1806 Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.” Lewisandclarkjournals. unl.edu, lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.jrn.1806-09-06#lc.jrn.1806-09-06.01. Accessed 13 Oct. 2021.

Williams, Hannah. "Saint Geneviève’s miracles: art and religion in eighteenth-century Paris." French History 30.3 (2016): 322-353.

Last updated: June 1, 2022