Last updated: September 10, 2021

Article

The St Croix Boom

By Dan Ott, PhD candidate in Public History/American History at Loyola University Chicago, 2013 for St. Croix National Scenic Riverway

Overview

From 1856 to 1914, the Boom was the epicenter of the St. Croix Valley’s logging industry. The Boom was located at a choke point on the St. Croix River at the head of Lake St. Croix near the sawmills of Stillwater. This location was ideal for sorting, scaling and rafting, as well as buying and selling pine timber that had been driven from upstream tributaries. This summary will describe the physical structure of the Boom from before its founding in 1856 at Stillwater to its ultimate commemoration in 1935 with a roadside historical marker as part of the second annual Lumberjack Days in Stillwater. Beyond detailing the changes in the location’s physical dimensions, this summary will also include information on the Boom’s operation, management, labor force and cultural significance as a point of industry, commerce and conflict. Emphasis will be placed on original research while content covered in secondary literature will be passingly referenced for further reading.1Narrative

The St. Croix Boom was built above Stillwater in 1856. “The Boom” (as it was referred to throughout the valley) was the terminal for logging operations in the watershed as the chokepoint where all of the water-driven logs were collected, sorted, scaled and rafted. As the exit point from the pinery, it was also a key marketplace where the abstract commodity of stumpage or pineland on paper became a finite material which could be bought, sold, moved and milled. These logs became the pine lumber that built the frame structures of the prairie frontier. The Boom operated for 58 years as the epicenter of the valley’s most important industry before ultimately closing in 1914.The Boom was located on the stretch of river just above Lake St. Croix, near Stillwater, to exploit the St. Croix Valley’s two great resources: white pine and water power. The pinery of buoyant timber was not located directly adjacent to the Boom Site, but rather upstream in a network of tributaries that drain some nine million acres of land into the St. Croix River.2 Loggers harnessed the power of the river’s current, augmented by logging dams and wing dams, to float their winter cut of logs on the spring floods from the remote regions of the valley to the markets of Stillwater and the Mississippi River. The Boom’s position above Lake St. Croix – the last 25 miles of river before its mouth on the Mississippi – ensured that the boom works collected both the largest possible number of St. Croix logs and made the best possible use of the St. Croix’s current.

Beyond the advantages of the Boom’s location relative to pine and water, the site was also selected because of its topographical and geological features. At this place, the river was divided by a series of narrow islands that created natural channels for sorting logs. Off the water, the banks of the St. Croix were lined with high bluffs and cliffs, which prevented the river from broadening and carrying the logs outside of the boom works. This ravine was referred to during the logging era as the “Boom Hollow.”3

Prior to the creation of the Boom, some of these rock faces were painted with Native American pictograms. Known as “Painted Rocks” to the white settlers, this area was an early tourist destination in the St. Croix Valley and upper Mississippi, as Americans visited to consider the primitive art forms of what they considered racially inferior Native Americans. Frontier historian J. Fletcher Williams’ 1881 record of this archaeological site made few observations of merit. Williams mostly resorted to racist assertions: the “rude taste of the savages,” the seemingly timeless quality of the “strange hieroglyphics” which were fully “intelligible to the Indian visitor” and every Indian’s seemingly obsessive “habit of performing ceremonies” at the cliff according to their “superstition.” Williams made no distinction amongst Native American tribes that visited the site, but did note that these remains were ultimately destroyed by the “blasting” of the Boom Company and the “wasting hand of time.”4 When Isaac Staples, the immigrated lumberman from Maine and future baron of the valley, first made plans to build the Boom above Stillwater in 1856, he referred to the site as “Painted Rock.”5

In order to build a boom across the St. Croix River, a charter was needed from either Minnesota or Wisconsin. The Confederation’s (pre-Constitution) 1787 Northwest Ordinance guaranteed that all navigable waterways were “common highways” to remain “forever free” and unobstructed for general use. Minnesota and Wisconsin territorial and state constitutions carried this environmental right as well. The exclusive charter of the St. Croix Boom Company, secured initially in 1851, allowed the company to partially obstruct the river with their boom, charge boomage (fees) and issue company stock in exchange for processing all of the logs that arrived and delivering them to their owners. While the amount of stock and boomage rose, they were fairly finite even if debatable. Obstructing the river, however, was destined to be the major point of conflict and legal reinterpretation throughout the Boom’s history. Jamming and obstructing the river with logs every summer prevented others, namely steamboat men, from securing their right to the “common highway.”6

The St. Croix Boom Company was first organized and secured its charter from the State of Wisconsin and the Territory of Minnesota in 1851 to build a boom on the St. Croix above Osceola. This was the first such boom charter in the Great Lakes states and set an important precedent for the logging industry in the region. The early company was owned by lumbermen from Taylors Falls, Osceola, Marine on St. Croix and Stillwater. These stockholders had been members of an earlier “Log Committee” of frontiersmen, who agreed to drive logs communally from the Falls to Lake St. Croix. A boom seems to have been the next logical step in their efforts to profit together from the pinery. Their boom was too remote from Stillwater, however, which was emerging in the 1850s as the major milling and population center of the valley. The boomage was not enough to cover the expense of delivering the logs 20 miles to mills downriver and the company faced serious financial difficulties throughout its early existence.7

In 1856, Isaac Staples along with Martin Mower and several other new investors initiated a reorganization of the St. Croix Boom Company. Staples and company bought out all but one (W.H.C. Folsom) of the previous owners, securing an amended charter from the Territory of Minnesota which allowed increased boomage fees, a larger capitalization and a second boom location above Stillwater. In that same year, the new owners secured the lands and islands in Sections 14 and 15 of Township 30 North, Range 20 West above Stillwater, which is still referred to as the St. Croix Boom Site. The company commenced building boom works at the new location. The new company was immediately more successful than its predecessor because it was able to capture and charge boomage for logs coming off of the Apple River – the largest tributary being logged at the time.8 The company continued to operate the “upper boom” at Osceola for some years, but this was ultimately abandoned because of concerns about sorting logs in an area that was prone to low water later in the season. The upper boom works were removed in the 1880s by the Army Corps of Engineers as an unnecessary obstruction to river navigation.9

Staples and Mower controlled the Boom Company as well as the lion’s share of the St. Croix pinery until 1889. In that year, the “Weyerhaeuser Syndicate” leased a controlling interest in the Boom Company and maintained it until the Boom closed in 1914. This transfer of power is a crucial turning point in the management of the Boom. Mower and Staples were considered leading citizens in the valley and the general impression is that they managed the Boom and their relationships in the St. Croix benevolently. They had diversified economic interests on the river and directly benefitted by keeping navigation lines open to steamboats, some of which they owned and which moved goods they sold to markets above the Boom. Frederic Weyerhaeuser and company, working through William Sauntry in Stillwater, managed the Boom as an extension of their complicated systems of corporations specializing in vertically integrating logging from land ownership to lumber yard. They had no interest in seeing other industries flourish and were said to run the Boom as an “octopus” and “monopoly” with no regard to others. Upon taking control in 1889, they set about “improving” the river extensively with more booms and piers to facilitate a larger flow of logs. Most importantly, they built Nevers Dam in 1890 to better control the flow of logs, preventing jams.10

The Boom as a Structure and Operation

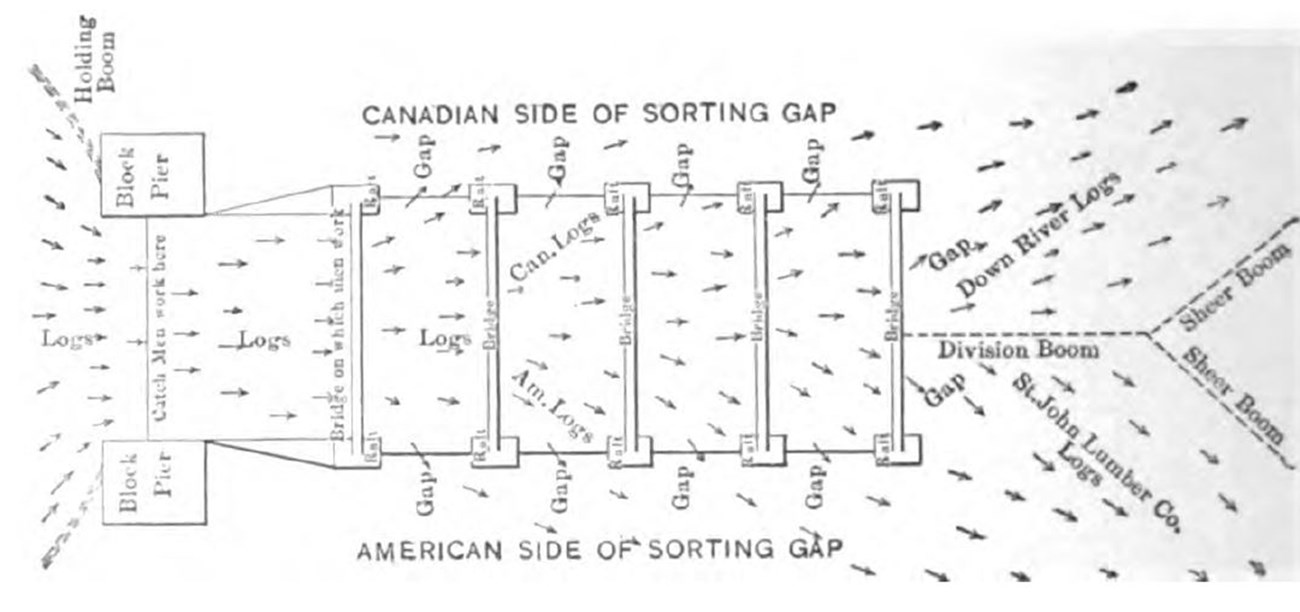

Discussion of the St. Croix Boom’s built structure can be divided in two parts. The first part is the boom works. The boom works were the complex series of piers, pilings and booms (floating log fences) that extended for miles of river, creating log channels, navigation channels, sorting gaps and holding pens for moving and organizing the vast quantities of timber that floated out of the watershed. The second part is the St. Croix Boom Company settlement. The settlement housed the rivermen that worked on the Boom, as well as the facilities of those who managed boom operations and log billing.Functionally the boom works were set up as the filter end of a funnel which drained pine out of the watershed. Most loggers drove the St. Croix’s high-water spring current to move their winter cut of pine timber from forest to market. In the 1880s and 1890s, up to 200 different companies operating hundreds more logging camps crammed more than 300 million board feet of logs into the river annually. Most of these log drives became intermixed and arrived near Stillwater in June and July every year. To resolve issues of ownership, each logging camp had a unique bark and log mark registered with the St. Croix’s surveyor general (over 2,000 unique marks in the 58 years of operations) The boom works made a wall of chain log fences and piers across the river (called a “catch boom”), stopping the drive and allowing “catch markers” to systematically mark the logs by owner. Afterwards other rivermen employed at the Boom floated the logs through the sorting gap to holding pens. 11

Image from Ralph Clement Bryan, Logging (New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc., 1913)

Holding pens were arranged along log-channel avenues with their own sorting gaps (see Figure 1). In holding pens, the logs were “checked” into brails (or brills). An old-time Mississippi raft pilot described a brail:

A brail of logs was six hundred feet long and forty-five feet wide. The rim was made of the longest logs fastened at the ends… by a short, heavy chain of three links. A two-inch hole was bored nine inches long in each log, and a two-inch oak or ironwood pin, with a head on it was put through an end link of the chain and driven hard into the hole in the boom log. These logs, so fastened made a strong boom or frame… into which loose logs were carried by the current, and skillfully placed endwise with the current, by men, using pike poles and peavies. Then one-half-inch cross wires were placed and tightened, to hold the boom and logs together and prevent spreading.12

John Runk, Washington County Historical Society

Once the brail was completed, the state appointed surveyor general or his deputies scaled the brail, assigning a unique brail number and measuring its volume in board feet. This process commodified the lumber, allowing the Boom Company to charge boomage fees for their services (per thousand board feet). The numerical abstraction of each brail meant that it could be objectively bought, traded or sold according to the volume affixed to its recorded brail number. After brailing and scaling, owners collected their timber, which they floated or towed by steamboat to nearby sawmills or rafting grounds. A raft was usually constructed of more than six brails arranged in rows of three, enclosed in another larger frame of log booms. These then were towed down river by steamboats.14

While discovering the process through which logs were sorted at the Boom is fairly easy, mapping its geographic layout as it ran up and down the river is much more difficult. There are no extant maps of the entire layout of the boom works, which undoubtedly grew over time and ultimately ran from Stillwater at least eight miles upriver, if counting continuous “improvements.” This distance is even further if including piers and dams which the Boom Company created as far north as Nevers Dam and more minor piers, booms and dams below the Dalles – all in service of sorting and driving logs. The sheer scale and difficulty of navigating the miles of boom works and “improvements” gave Major Faruquhar of the Army Corps of Engineers pause. He suggested in 1875 that “if the United States is to improve this river by removing natural obstructions some provision must be made to prevent the placing of artificial ones [such as piers, cribs and pilings].” 15

The mass of “artificial” obstructions was constructed to suit specific purposes and then abandoned when river operations moved elsewhere. Pilings 40 feet long were driven using waterborne pile drivers. Piers were constructed of log cribs filled with rock on ice during the winter. These structures were built adjacent to pilings and then cut through the ice, free to sink into the river. If they were too shallow, additional cribs were built on top and eventually covered in planks. They were rarely removed except by the Army Corps of Engineers or direct legal threat. 16

John Runk Courtesy of Washington County Historical Society

A general description of the boom works’ layout can be cobbled together from many sources throughout the St. Croix Boom’s history. The earliest sorting gap was likely just above Stillwater near the Boom settlement in Section 15. By the 1880s, however, the sorting boom and gap were in between an island and the Minnesota bank, five miles upriver from Stillwater across from “Herrimann’s landing not far from the Old Railway Bridge Pilings.”

17 Above the sorting gap, the Boom Company and later the Army Corps of Engineers created log and navigation channels interwoven with the Stillwater islands. The Army Corps maintained a navigation channel from Arcola to below Stillwater beginning in 1883.18 These channels needed to be extended up river almost continuously through the 1890s as a larger volume of logs crammed into the river every spring and filled the logging channel, spilling into the navigation right-of-way.19

Chester Sawyer Wilson, courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society

Below the sorting gap, the boom works were divided into channels creating holding pens. William Rector noted that the boom works could expand or contract based on the volume of logs using a swinging “sheer boom,” a more solid hinged log boom which could swing open or closed between islands.21 The upper portion of the Boom was a set of three channels in which logs were pulled out of the center into brails on either side.22 At the southern end of this portion, the sheer boom allowed the brails to either be floated directly out of the boom works (if there were less logs) or diverted into another set of holding pens, piers and booms as the river opened into Lake St. Croix.23 After these final holding pens ran about three miles of privately-managed rafting grounds.24

When the Boom closed in 1914, most the boom works vanished. Pilings and crib wood were pulled and sold to wring the last dollars out of the St. Croix’s cut-over landscape. Only the occasional rotted pilings broke the river’s surface in low water and most of those were pulled as they were discovered to prevent pleasure boat accidents. A picture taken at the Boom Site by John Runk in 1917 shows no signs of the industrial river only three years after the Boom’s close. 25

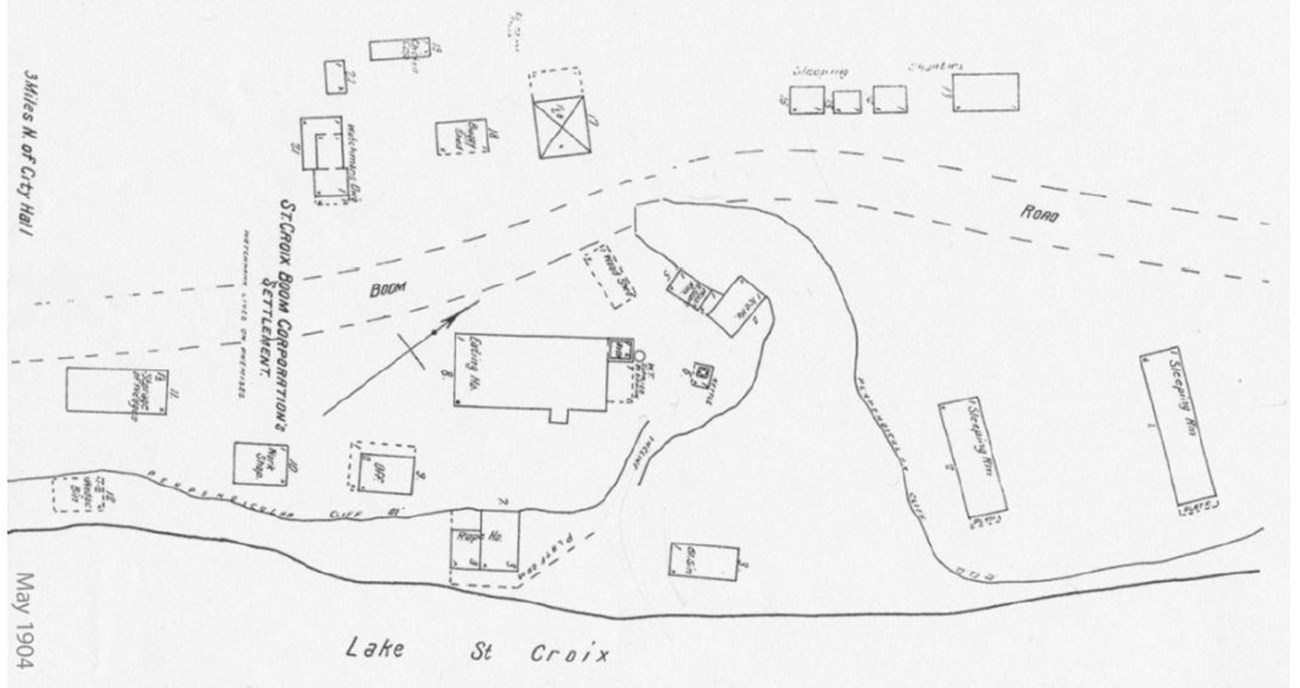

While there are few archival and archaeological remains of the boom works, quite a bit more has been left behind to chronicle the operational headquarters, housing and storage of the St. Croix Boom Company settlement. This documentation is so much better than the boom works, because the settlement was built on purchasable real estate and its numerous structures warranted insurance policies and maps. Moreover its structures were more unique and valuable than the nondescript miles of log booms and piling that made up the works. While the Boom was closed in 1914 and most of the buildings were torn down, the Boom house and barn were preserved and the larger property became a Minnesota Highway Department roadside rest area. These insured that there was at least some apparent archaeological evidence of the settlement.

John Runk Courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

While most of these structures have been torn down, several remain. The St. Croix Boom house and barn have been jointly listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1980, standing across Highway 95 from the Boom Site. The Queen Anne-style house was built in 1885 for the boom master, Frank McGray. McGray began working for the Boom Company in 1856 and managed the works from 1885 to 1905. Apparently he purchased the house from the company in 1895 and lived there until 1919. 29 Also extant is the cook shanty’s cave cellar and elevator shaft, which can be accessed from the river shore.30

courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

Social and Cultural History of the St. Croix Boom

The Boom was the center of the St. Croix logging industry and commerce on the river. During the summer, mill owners, river men, raft pilots, loggers and log dealers converged on the Boom. River pigs drove logs to the sorting boom. Once there, catch markers carved new log marks onto each log indicating its owner. Boom men checked and guided logs through the gap, prodding them to their appropriate holding pen. Still more men danced along booms and loose logs, tethered by lengths of rope to pilings, pulling each log into position in its brail. Stringers busily tied each log into position, as the next log drifted to its side. As brails were completed and closed, six deputy surveyors and their tallymen rowed up in skiffs to scale each brail and record its volume. Finished brails were fixed to small tow boats and brought to rafting grounds or nearby mills, making room for more. Log buyers, millers and sellers patrolled the entire boom works peddling brails and unsorted logs alike. In Stillwater, river men and boom men went to cash their time checks at the St. Croix Boom Company’s Chestnut Avenue office. Then they hit the local drinking establishments with pockets full of cash. When they arrived, the locals stayed home and hoped for the best. 31Meanwhile on the same river, steam packets moved through the navigation channel towards Taylors Falls. If the log channel was jammed and spilled into the navigation channel, as it usually did, the boats above the Boom were trapped. These steam packets usually signed contracts with the Boom Company to move goods up river. Steamers downstream of the Boom made contracts with the Boom Company to complete deliveries northward as the Boom Company attempted to manage the ill effects of its industry. These log blockades could last from early June into August. The arrangement also meant that steamers above the Boom had to wait until the end of the logging season to get paid by the Boom Company for any of their work.32

The annual log jams made the Boom the subject of much conflict amongst lumbermen, merchants and steamboat men. While the company was legally obligated to keep the river clear as a common highway, log jams at the Boom or at the Dalles frequently prevented them from making good on that promise. By 1888, the State of Wisconsin had ruled that the Boom Company was negligent in all instances of log jams caused by backups at the sorting gap. In particular, the case referred to an 1883 jam that extended five miles beyond Marine – putting sawmills in that town out of business. The Boom Company’s solution to this legally sanctioned liability was to construct Nevers Dam 12 miles above Taylors Falls. Instead of jamming the river with logs, the Boom Company left it dry, releasing water only when it was sluicing logs. The company’s literal control of the water level became the major critique of the “octopus” throughout the valley, although minor lumbermen certainly resented paying boomage to the “river monopoly” as well. 33

The Army Corps of Engineers’ chief task was maintaining the navigation channel on the St. Croix for steamboats and it was often drawn into the controversy over navigational rights. The biggest controversy over Nevers Dam and navigation came to a head in 1899 after the U.S. Congress passed a new River and Harbors Act. This act made obstruction or alteration of a river way illegal, except with authorization from the Army Corps’ chief engineer. This act made the entire boom works illegal unless approved by the Corps. Loggers, steamboat men and merchants alike immediately began lobbying the Corps’ St. Paul District office for consideration. After public hearings in 1900, the Corps, with some urging from Frederic Weyerhaeuser, ultimately condoned the Boom and Nevers Dam, only guaranteeing steamboat navigation of the St. Croix on Independence Day, Memorial Day, and throughout August and June. Other than those two months and two days, the river belonged to the “octopus.” W.H.C. Folsom vigorously protested the decision as a violation of “our inalienable rights to an open and un-obstructed navigation of the St. Croix.” The old-time logger, steamboat man and historian from Taylors Falls believed his right to the “common highway” was on par with the Bill of Rights.34

Beyond these public battles for control over the river, there is very little information available about the lives of the men that actually walked the boom works. For the most part, it can be assumed that their work was very similar to that of river pigs who drove the logs from the pinery to the Boom. Boom workers, too, walked the logs on the river in calked boots bearing pikes and peavies. They likely wore the same sort of mackinaw jackets and wool pants. The Boom settlement was much the same as a logging camp as well, but closer to “civilization.” Men lived in cramped bunk shanties and ate for free at the cook house while supposedly working from dawn to dusk.35

Consideration of the type of people boom men were is necessarily abstract thanks to the shortage of sources. Amongst historians of the Great Lakes lumber industry, there are two predominant schools of thought on logger-laborers. The first and more highly romanticized is that these men were immigrant farmers (hardy Scandinavians) who worked in the pinery over the winter until they turned the corner at their homesteads. The second is that these men were transient laborers of a degraded moral condition. They lacked the fortitude to make an honest living or settle down, moving with seasonal jobs, spending their money at saloons and brothels, raising hell wherever they went.36

The reality is probably a combination of these two archetypes. The romantic vision is supported by scores of oral histories throughout the Upper Midwest of lumberjacks turned farmers or merchants. These men stayed around long enough to have their stories recorded and placed themselves in a positive light as hardworking and frugal new Americans with a sense of obligation to their families – the “right” kind of people. Alternatively, Progressive era sources from the early 1900s continuously refer to the degraded condition of lumberjacks. Newspapers warned and belittled lumberjacks that started riots and “rows,” while residents avoided main streets when logging drives arrived. Brothels and saloons lined the streets of lumber towns like Hayward and Stillwater. To support such institutions, not every logger could be the frugal, hardworking family man of romantic lore. 37

Within the spectrum from saintly immigrant to transient troublemaker, boom laborers were both. The 600 laborers that worked at the Boom daily were most likely to be either transients or young men (and boys) earning extra money for their families. As a seasonal facility, the Boom opened June 1 and closed when all of the logs were sorted from the river, usually in August but sometimes as late as October. This sort of schedule lent itself well to transient laborers that might be able to work in the pinery during the winter, drive logs in the spring, boom logs in the summer and harvest grain into the fall. It is unlikely that boom men were also farmers, given this summer workload. Farm families were, however, willing to spare their boys during the busy period on the farm in exchange for wages.

The best information on the rivermen of the Boom comes from 1902 when Stillwater Saw Millers and Rivermen unionized to secure a 10-hour workday. In late May of that year, a union drive and strike shut down all of the Stillwater, South Stillwater and Oak Park sawmills for one week. In sympathy, many rivermen and rafters also went on strike, although 200 men and boys remained working at the Boom. The strikers formed the blanket “United Mill Men of the St. Croix Valley” to bring together all of the trades associated with the logging industry, electing Edward Haggerty president of the union. After a widely publicized week of meetings, speeches and processionals through town, the mill men won a 10-hour day for 11-hour pay. On June 2, the mills reopened at 10 hours a day and the Boom continued at the usual 11 hours. After his milling victory, President Haggerty brought union demands to William Sauntry, the president of the Boom Company. He was rebuffed and Sauntry threatened a lockout. Predictably, the victorious mill men offered no sympathy to the rivermen’s cause and the Boom continued uninterrupted. By late July, however, Haggerty had found leverage against the Boom Company, without requiring support from his rank-and-file millers.

38

That summer, the Boom Company had been investigated by a Minnesota deputy commissioner of labor and was found to employ 50 children under the age of 16 out of a total 205 employees, about 24% of the workforce. It is most likely that these children were stringers because of the relative lightness of the tying and looping rope and the sheer number of stringers required to tie logs into brails. Child labor being illegal in Minnesota since 1885 (with some exceptions), the Commissioner of Labor required the Boom to dismiss these young employees. By late July, Boom Superintendent Frank McGray had begun re-hiring children – supposedly capitulating to pleas from parents that needed additional wages from their boys to keep their families from want. Haggerty reported McGray to the Department of Labor for another violation on a particularly egregious-case, Joseph Roy – an 11-year-old. On July 23, Deputy Labor Commissioner E.B. Lott swore out a warrant against Frank McGray and he was arrested later that day. The charges did not stand and, after posting bail, paying court fees, and promising not to employ children again in the future, the case was dismissed on July 31.39

Christopher Carli, courtesy the Minnesota Historical Society.

In comparing the millers’ and rivermens’ strikes of 1902, it is apparent that the rivermen most likely failed because they were unskilled transient drifters and children. Newspaper coverage of the two were patently different as the Gazette wrote more in a week about the millers’ strike than it did over the five weeks of the Boom strike/lockout. The paper mainly fretted over the ill effects of the Boom strike on the milling and rafting industry as well as the valley’s economy at large. This is likely because while the millers marched and held organizational meetings with grand speeches, the transient rivermen did not take their politics to the streets. They just left town to find other work. The Washington County Journal reported just days after the lockout began that “most of the men who refused to work eleven hours a day and came down to town, have gone elsewhere to seek employment.” Moreover, Haggerty could not organize a strike earlier in the summer on the tales of the millers’ success, because boom work was so comparatively unskilled that it could be done by children – undermining union efficacy and rivermen solidarity.41

It seems doubtful that the Boom strike represented more than the will of Edward Haggerty. The union’s mild (and gutless) decision to communally show up late to work on August 6 rather than openly strike indicated its weakness. This action, however, initiated William Sauntry’s decision to lock out the Boom workers. The lockout made the union look stronger than it really was and by the time the lockout ended, most of the transient boom workers had gone elsewhere for seasonal wages. For the next two weeks, Haggerty’s strike looked strong, but probably did not represent all that many men who were “holding out.” Indeed, the Boom strike was not even mentioned during the hoopla and speeches of Stillwater’s first Labor Day celebration, which occurred at the same time. Ultimately, when Haggerty called off the strike, he stated that the union was not caving to the Boom Company, but was rather initiating action in sympathy for the milling interests (and their own rank-and-file mill workers) who had been without logs to mill. Ironically, when the union ended the strike, very few of the previous employees were hired back. Most had left and the few “old men” still around claimed that “they will stand out against an 11 hour day” and refused to return to work.42

The difference between the rivermen’s failure and the millers’ success was the difficulty and relative respectability of their labor. Sawmills could not find an entirely new skilled workforce and so capitulated to workers they already paid fairly well ($8/day). Meanwhile the Boom Company could find anybody, even children, to sort logs for comparatively little pay ($1.75/day). This substantial difference in pay accounts for the very wide gap in commitment to the unionization and strike efforts of the millers and the rivermen.43

Commemoration

The last log passed through the St. Croix Boom on June 12, 1914. After a reunion, some photographs and speeches, Frank McGray, who supposedly worked on the Boom in 1856, tied the last log into the last brail. The white pine logging era opened and closed in the St. Croix Valley during one man’s lifetime. The pinery had been cut over and most of the major companies in the lumber business had moved onto the North Woods of Minnesota and eventually would go further to the Pacific Northwest to continue cutting down pine. After the brail floated down river, men began to deconstruct the boom works as well as the settlement, salvaging saleable timber or goods.44The Boom Site took its modern form as a Minnesota Highway Department roadside picnic area in 1935. After the close of the Boom, the Boom Road had been maintained by Washington County as part of a trunk highway on the west bank of the river. This dirt and gravel road was called “the Marine Road.” In April 1933, the “Marine Road” was designated part of the Minnesota state highway system and was renamed Trunk Highway 95. The state highway system had been expanded with impetus from the federal government, which was making additional funds available for infrastructural improvement. The old Boom Road would be enhanced, graded, tarred and oiled by local laborers paid with New Deal money (the National Industrial Recovery Act) expended in the first year of Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency. Indeed the Great Depression had created such desperate economic circumstances that the road work on Highway 95 began during the winter to get the project rolling as fast as possible. The work was ultimately finished in October of 1934, and the highway was slated to be designated a scenic parkway.45

The St. Croix River Improvement Association lobbied the Minnesota Highway Department heavily in 1933 for the Marine Road’s inclusion in the state highway system. They also sought federal funds for its completion as well as its designation as a scenic parkway. The highway initiative fit into the Association’s larger goal of attracting outside dollars to the valley through whatever means possible. During the same year, they also lobbied for improvement of the St. Croix River channel and discussed means for improving the river for game fishing. The group saw everything as an opportunity to jumpstart the region’s economy using the river as its principle asset, ranging from nature tourism on the river bank, to fishing or barge traffic.46

The Boom Site picnic area was initiated by the Minnesota Highway Department in 1935. The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1934 and 1935 mandated that at least one percent of federal funds be spent on roadside development. Some of this money was designated to make the St. Croix Boom Site into a picnic area. The work of landscaping and building shelters, retaining walls and scenic overlooks was commenced by the National Youth Administration – another New Deal agency – in 1935 and completed in 1939. When the Highway Department rolled out their plan for the area in September 1935 they also included a historic marker to commemorate the St. Croix Boom Site.47

Creation of the picnic area and the marker had been lobbied by the Stillwater Junior Chamber of Commerce. The “Jaysees” planned on dedicating the marker to kick-off their second annual Lumberjack Days celebration. The Minnesota Historical Society was also involved in the project as the state’s historical authority, insuring the accuracy of the marker’s plaque. Although because of the scarcity of “objective,” information about the Boom, most of the content came from John Runk – a former river man turned St. Croix photographer and historian.48

The Boom Site Historic Marker was dedicated at 2:00 p.m. on October 10, 1935. The marker was surrounded by Stillwater’s men, women and children as well as tourists, all suffering through the Depression and dressed like old-time river pigs and lumberjacks - the very sorts that the established residents of Stillwater had loathed throughout the logging era. In a moment steeped in irony, the businessmen of Stillwater hoped to jumpstart their tourist economy by romanticizing the very “octopus” that the previous generation of merchants despised.49

John Runk, courtesy Washington County Historical Society

2 William Rector, “The Birth of the St. Croix Octopus,” Wisconsin Magazine of History, Vol. 40, No. 3 (Spring 1957): 171. [Included in digital collection].

3 J. Fletcher Williams, the History of Washington County and the St. Croix Valley (Minneapolis: North Star Publishing Company, 1881): 489. [Available on Google Books]

4 Ibid., 496.

5 Hersey, Staples & Co. to Schulenburg, Boeckler & Co., Correspondence, January 1, 1856, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, Minnesota [hereafter MHS] in Hersey, Staples and Company Papers, Box 4, 147.D.1.10F. [In digital collection]

6 William Rector, Log Transportation in the Lake States Lumber Industry (Glendale, CA: A.H. Clark Co., 1953): 172-189. Eileen M. McMahon and Theodore J. Karamanski, Time and the River: A Historical Resource Study of the Saint Croix National Scenic Riverway (Omaha, 2002): 76-77.

7 McMahon and Karamanski, Time and the River, 76-77; The St. Croix Log Committee, Agreement, July 17, 1850, W.H.C. Folsom and Family Papers, MHS, Box 123.D.15.2F [In digital collection].

8 Of all topics related to the St. Croix Boom, ownership and business organization has received by far the most attention. This is probably because period and subscription histories from the 1880s through 1920s were most likely to include information about who owned what and fought with whom, rather than extensively detailing how a seemingly common-place facility like the boom works actually operated. Moreover these histories did little to document the social history of lumbermen and rivermen as they lived and worked. The best example of a period history is W.H.C Folsom, Fifty Years in the Northwest (St. Paul: Pioneer Press Company, 1888):696-698 [available on Google Book]. The best historical works discussing the topic of ownership and organization are Rector, Log Transportation, 115-146; William Rector, “The Birth of the St. Croix Octopus,”; Agnes Larson, “When Logs and Lumber Ruled Stillwater,” Minnesota History, Volume 18 (June, 1937): 165-179 [in digital collection]; and Ralph Hidy, Frank Hill and Allan Nevins, Timber and Men: The Weyerhaeuser Story (New York: MacMillan, 1963).

9 Hersey, Staples & Co. to Judd, Waler & Co, April 19, 1856, Correspondence, MHS, Hersey, Staples and Company Papers, Box 4, 147.D.1.10F. [In digital collection]. Annual Report of the Army Corps of Engineers, 1875 (Washington, D.C.: 1875): 373-374.

10 William Rector, “The Birth of the St. Croix Octopus”; Hidy et al, Timber and Men; James Taylor Dunn, The St. Croix (St. Paul: The Minnesota Historical Society, 1979): 99-114 [in digital collection]; McMahon and Karamanski, 93-101.

11 William Rector, “The Birth of the St. Croix Octopus,” Wisconsin Magazine of History, Vol. 40, No. 3 (Spring 1957): 175-176. [In digital collection ].

12 Walter A. Blair, A Raft Pilot’s Log: A History of the Great Rafting Industry on the Upper Mississippi, 1840-1915 (Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1929): 51. [In digital collection ] Online: http://greatriversnetwork.org/index.php?brand=cms.

13 John Runk, “Hitching Logs into brills on the St. Croix Boom,” Photograph (Stillwater, MN,:1907), ID: Runk 141 Minnesota Historical Society Digital Collection, Online: http://greatriversnetwork.org/index.php?brand=cms. Barnes Mercord, Oral History Interview, August 1, 1972, River Falls Oral History Project, UW: River Fall Area Research Archive, River Falls Mss AW, Box 3, stated that as teenagers Barnes and his friends would row out to rafts and steal loose logs from within the brails. They would then sell them back to logging companies. On occasion they were run off by Raft Pilots and may have been shot at. Episodes of log thievery were regularly reported in the newspapers and were under the jurisdiction of “river police” who were privately contracted agents with the Stillwater Lumbermen’s Exchange to oversee log property rights on the river.

14 William Rector, “Lumber Baron’s in Revolt,” Minnesota History, Volume 31 (March, 1950): 33-39 discusses the role of the surveyor general and the politics surrounding the appointment. Blair, A Raft Pilots Log, 51, describes the rafting process.

15 Eileen M. McMahon and Theodore J. Karamanski, Time and the River: A Historical Resource Study of the Saint Croix National Scenic Riverway (Omaha, 2002):98-99. Annual Report of the Army Corps of Engineers, 1875 (Washington, D.C.: 1875): 374. Annual Report of the Army Corps of Engineers, 1879, Part II (Washington, D.C.: 1879):1182.

16 “The St. Croix Boom Company,” St. Croix Union, March 21, 1856. “Stillwater,” The Minneapolis Morning Tribune, October 4, 1910.

17 In “Wyman X. Folsom’s navigational map of the St. Croix River, 1860s and 1870s,” W.H.C. Folsom and Family Papers, MHS, location: +331, [In digital collection ] created as a memory map by Folsom in 1926 the sorting boom and gap are the only fixed structure of the entire boom works and were located across from Herriman’s landing. In “J.S. Keator Lumber Company vs. St. Croix Boom Corporation,” Reports of the Supreme Court of Wisconsin, Volume 71, (1888): 66 [available in “Court cases” folder] the St. Croix Boom Company only claimed to control four miles of river, from their sorting gap across from Titcomb’s landing (which may be the same as Herriman’s landing and the difference in naming can be credited to the 38 year difference between the two sources) down to one mile above Stillwater. I am still a bit unsure of the exact location, not having investigated on the River, to compare against the several good images of the sorting gap that are extant in the John Runk photo collection, “Logs passing through the Gap of the St. Croix Boom,” ID: Runk 140 and “Gap of the St. Croix Boom,” ID: Runk 142 both in the Minnesota Historical Society Digital Collection, Online: http://greatriversnetwork.org/index.php?brand=cms.

18 Darling, “Field-Book St. Croix, Oct. ’83,” in NARA Chicago, Corps of Engineers, Record Group 77, Box 60 [in digital collection].

19 Chester Sawyer Wilson, “St. Croix at the Boom looking north,” Photograph, 1903, ID 30859, the Minnesota Historical Society Digital Collection, Online: http://greatriversnetwork.org/index.php?brand=cms, gives a clear sense of how logs built up in the two log channels and could spill into the navigation channel.

20 J. Fletcher Williams, the History of Washington County and the St. Croix Valley (Minneapolis: North Star Publishing Company, 1881):183-184 [Available on Google Books].

21 Rector, Log Transportation, 134-134, describes the layout of the boom based on his interview notes with John Runk, Homer Canfield and Mark H. Barron during the early 1950s. All three were rivermen and none of these interviews of notes are extant.

22 In the background of John Runk, “Buildings of the St. Croix Boom Company,” 1898, Photograph, ID: Runk 135 in the Minnesota Historical Society Digital Collection, Online: http://greatriversnetwork.org/index.php?brand=cms, the channels of the river and the sheer boom can be seen at the head of Lake St. Croix.

23 John Runk, “St. Croix River above Stillwater,” 1911, Photograph, ID: Runk 1184 in the Minnesota Historical Society Digital Collection, Online: http://greatriversnetwork.org/index.php?brand=cms.

24 J.S. Keator Lumber Company vs. St. Croix Boom Corporation,” Reports of the Supreme Court of Wisconsin, Volume 71, (1888): 66 [in digital collection]. John Runk, “View of the St. Croix Showing Log Rafts,” 1911, Photograph, ID: Runk 125, the Minnesota Historical Society Digital Collection, Online: http://greatriversnetwork.org/index.php?brand=cms.

25 “Boom Finishes Sorting Logs,” The Stillwater Daily Gazette, June 13, 1914. John Runk “St. Croix River at the Boom Site,” 1917, photograph, ID: Runk 1190 in the Minnesota Historical Society Digital Collection, Online: http://greatriversnetwork.org/index.php?brand=cms.

26 Map 32, “Stillwater, Minnesota,” 1910, Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps [Included in “Maps” folder].

27North West Publishing Company, Plat book of Washington County, Minnesota (Minneapolis, North West Pub. Co., 1901): 17 [Included in “Maps” Folder].

28 John Runk, “Cook Shanty at the St. Croix Boom,” 1910, ID: Runk 143; “Buildings of the St. Croix Boom Company,” 1898, ID: Runk 135; “Office of the St. Croix Boom Company,” 1886, ID: Runk 132, the Minnesota Historical Society Digital Collection, Online: http://greatriversnetwork.org/index.php?brand=cms.

29 Peggy Lindoo, “St. Croix Boom Company House and Barn,” National Register of Historic Places – Nomination Form, Listed June 6, 1980; National Register Number 80000409, Available Online at through the MN SHPO office at the Minnesota Historical Society, http://nrhp.mnhs.org/NRDetails.cfm?NPSNum=80000409.

30 “St. Croix Boom Site Roadside Parking Area,” MNDOT Historic Roadside Development Structures Inventory, SHPO Inv # WA-SWT-004 [Available in “Government Reports” Folder].

31 Rector, “St. Croix Octopus,” 173; Edgar Roney, Looking Backward: A Compilation of more than a century of St. Croix Valley History (Stillwater: 1970). As a lumber speculator, Zina Chase wandered around the boom works with prospective buyers and sellers in the summer of 1866. Zina Chase, Diary 1866-1867, MHS, P2076 [in digital collection].

32 James H. McCourt describes being a steamboat clerk aboard the G.B. Knapp in the summer of 1867. They become trapped above the Boom for 61 days and by the end of the season he is still owed $300 by the Knapp for services rendered to the Boom. James McCourt Diary, January 1 – November 21, 1867, MHS, P968 [In digital collection].

33 The 1888 court case may have led Mower and Staples to be willing to part with their Boom Company stock, leasing it to the Weyerhaeuser Syndicate. Within one year of the Weyerhaeuser take-over, the Company had built Nevers Dam, resolving the liability. “Keator Lumber Company vs. St. Croix Boom Corporation,” Reports of the Supreme Court of Wisconsin, Volume 71, (1888): 62-102 [in digital collection].

34 Raymond Merritt, Creativity, Conflict & Controversy: A History of the St. Paul District U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Washington DC: US Gov't Printing Office, 1979): 270-291 [in digital collection]. W.H.C. Folsom, “At A Meeting of the citizens of St. Croix falls,” February 21, 1900, MHS, WHC Folsom Papers, Box 123.G.12.1B-2, Volume 29 [available in “Archival Resources” folder].The Stillwater City Council backed the ACE decision and their resolution to that effect summarizing the importance of logging to the river is in “Resolution #101583,” Stillwater City Council Resolutions, Volume 4, 574, MHS, Stillwater: City Council Resolutions, 1892-1904, 112.H.9.7B-2 [in digital collection]. These two documents are in direct conversation with each other and would make good interpretive examples. It is also worth noting that the Boom made claim to the “common highway” (or unobstructed navigation) whenever new bridge plans were discussed. In 1871, the river loggers protested the construction of a railway bridge at Hudson built upon narrow pilings. When the railway contractors ignored a legal injunction against the construction, steamboat men literally went down river from Stillwater and tore up all the pilings. This episode s referred to as the “Battle of the Piles.” James Taylor Dunn, The St. Croix, 145-150 [available in “publications” folder]. In 1875, Isaac Staples protested the creation of a bridge from Stillwater to Wisconsin for farmers, claiming that it would disrupt log rafting. The City Council put the matter to a popular vote and the toll bridge prevailed. Stillwater City Council, February 16, 1875; March 23, 1875, Meeting Minutes, Volume 3, 382, 392, MHS, Stillwater: City Council Minutes, 1861-1888 and Ordinances, Box 118.J.18.7B.

35 For a good description of river pigs and their work see Rector, Log Transportation, 91-99.

36 Theodore Karamanski, Deep Woods Frontier (Detroit: Wayne State Press, 1989) represents the romantic memory of lumberjacks utilizing memory sources. Frank Higbie, Indispensable Outcasts (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003) discusses the negative perception of seasonal workers and their absolute necessity to evolving economies of scale. Troy Henderson, “Shanty-Boys, Lumberjacks and Loggers,” Unpublished Dissertation, Loyola University Chicago, 2009 [in digital collection] touches on this conversation about lumberjacks as does chapter three of Kevin Brown, “The Great Nomad: Work, Environment and Space in the Lumber Industry of Minnesota and Louisiana,” Unpublished Dissertation, Carnegie-Mellon University, 2012 [in digital collection].

37 Good examples of reports detailing the degraded condition of loggers are Industrial Commission of Wisconsin, “Labor Camps in Wisconsin,” (Madison: 1913), Christopher Thurber, “Uplifting the Lumberjack,” Harpers, October 23, 1909 and Burt Kirkland, “Effects of Destructive Lumbering on Labor,” Journal of Forestry, Volume 18 (1920): 318-320 [in digital collection]. Newspapers reporting disturbances from loggers are ubiquitous from the region during the era, but “Rows in Stillwater,” the St. Croix Union, March 28, 1856 [in digital collection] is one such example.

38 “Stillwater,” Minneapolis Tribune, June 4, 1902; “Stillwater,” Minneapolis Tribune, June 5, 1902. “Sawmills closed,” Stillwater Daily Gazette, May 26, 1902; “Strike is General,” Stillwater Daily Gazette, May 27, 1902; “Organize Unions,” Stillwater Daily Gazette, May 28 1902; “Mills Humming,” Stillwater Daily Gazette, June 2 1902,

39 “Labor Law Violated,” Stillwater Daily Gazette, July 23, 1902; “Dismiss the Case” Stillwater Daily Gazette, July 31, 1902; “Must Not Employ Children,” Washington County Journal, July 25, 1902; Eighth Biennial Report of the Department of Labor of the State of Minnesota, 1902 (St. Paul: Pioneer Press Publishing, 1902):417-418, 460, 472, 558, MHS, Minnesota State Archives, Labor and Industry Reports, Box 119.C.4.F (B).

40 “Rivermen Talk Boom Strike,” Stillwater Daily Gazette, August 5, 1902; “Boom Shuts Down,” Stillwater Daily Gazette, August 8, 1902; “Will Open Gap,” Stillwater Daily Gazette,” August, 23, 1902; “St. Croix Boom Running,” Stillwater Daily Gazette, August 27 1902; “A Small Crew,” Stillwater Daily Gazette, August 28, 1902; “Boom Strike Ends,” Stillwater Daily Gazette, September 15, 1902; “Break the Record,” Stillwater Daily Gazette, December 1, 1902.

41 Notes, Washington County Journal, August 15, 1902.

42 “Labor Day Speeches,” September 2, 1902. “Boom Strike Off,” Stillwater Daily Gazette, September 15, 1902.

43 “Sawmills Closed,” Stillwater Daily Gazette, May 26, 1902

44 “Boom Finishes Sorting Logs,” Stillwater Daily Gazette, June 13, 1914.

45 “New Roads Added to Highway System,” The Stillwater News, April 21, 1933. “Local Labor Will Get Preference,” The Stillwater News, July 14, 1933; “Winter Work on Highways Planned,” August 25, 1933; “Marine Road to Open Oct. 1,” The Stillwater News, August 3, 1934.

46 “River Groups Urges Road Completion,” The Stillwater News, May 25, 1934; St. Croix River Improvement Association, Minutes of Meetings, 1933-1935, MHS, St. Croix River Association Records, Box 145.L.12.8F.

47 Biennial Report of the Commissioner of Highways of Minnesota for 1935-1936 (St. Paul: 1937):28-31 includes pictures of the “Roadside Parking Area” at the Boom Site. “St. Croix Boom Site Roadside Parking Area,” MNDOT Historic Roadside Development Structures Inventory, SHPO Inv # WA-SWT-004 [in digital collection]. “State Plans Picnic Area,” Stillwater Daily Gazette, September 16, 1935.

48 “Work is Started on the Jaysee Boom Memorial,” Stillwater Daily Gazette, September 26, 1935. John Runk, “St. Croix Boom Marker,” October 9, 1935, Photograph, ID: Runk 1180, the Minnesota Historical Society Digital Collection, Online: http://greatriversnetwork.org/index.php?brand=cms.

49 “Colorful Lumberjack Fete Opens,” Stillwater Daily Gazette, October 10, 1935.