Last updated: January 24, 2021

Article

Stalwarts, Half Breeds, and Political Assassination

wikipedia.com

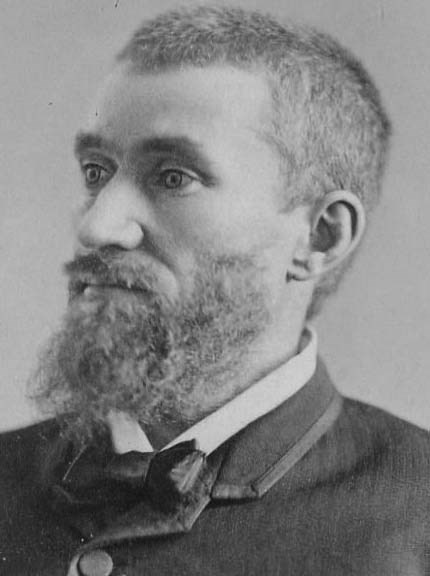

Most summaries of the assassination of President James A. Garfield describe his attacker, Charles Guiteau, as nothing more than a “disappointed office seeker.” When police apprehended him after he shot Garfield on July 2, 1881, Guiteau calmly told them, “I am a Stalwart of the Stalwarts…Arthur is president.” Were these just the ramblings of an almost surely mentally unbalanced murderer? Or was there something more to Guiteau’s statement? Understanding the factionalism in the Republican Party during this era helps one understand not only how James A. Garfield ascended to the presidency, but also that his murder was wholly political in nature.

One main issue led to the split in the Republican Party: patronage. Under the patronage system, the winners of congressional and presidential elections had the power to appoint whomever they chose to fill numerous federal jobs. Experience and qualifications mattered little (if at all). Powerful politicians loved the so-called “spoils system” because it allowed them to put friends and relatives into lucrative positions and ensure loyalty from everyone they appointed. According to author Kenneth D. Ackerman, “Senatorial courtesy—deferring to senators of the president’s party on local positions—helped the party in power to build a national base. Breaking the system apart would threaten everyone.” Senator Roscoe Conkling of New York was the undisputed king of the patronage system, and the key weapon in his spoils arsenal was the position of Collector of the Port of New York.

wikipedia.com

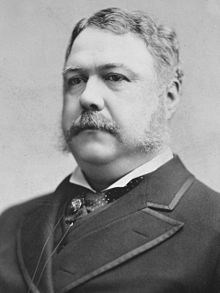

Much of the nation’s trade flowed through the Port of New York. Because the Collector of Customs there received a percentage of the customs duties, the job was the most prized appointment in the country. Roscoe Conkling demanded that he alone select the man to fill this politically important and personally lucrative position. President Hayes, seeking to wrest control from Conkling, nominated two different men as Collector. Conkling rallied his Senate colleagues to defeat both and eventually succeeded in getting his own choice, an acolyte named Chester Alan Arthur, appointed instead. In 1878, President Hayes and Secretary of the Treasury John Sherman fired Arthur from his position for turning a blind eye to corruption inside the Customs House. In response, Conkling had Arthur named chairman of the New York Republican committee and made plans to have Arthur elected as the junior U.S. Senator from New York in 1880.

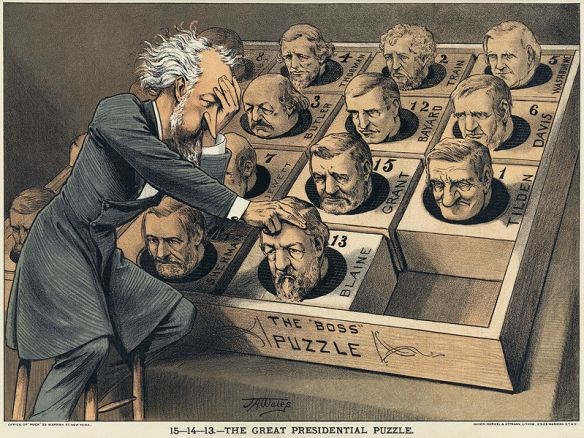

Led by Conkling, Stalwarts encouraged former president Ulysses S. Grant to seek an unprecedented third term in the White House in the 1880 election. Despite the many scandals of Grant’s two previous terms (1869-1877), the former Union general was still immensely personally popular with the American public. Grant was disheartened at Hayes’s attempts to dismantle the patronage system and, in consultation with Conkling and other Stalwart allies, agreed to run again. Conkling looked forward to reclaiming control of the New York Customs House and once again serving as President Grant’s right hand man, just as he had done during the earlier Grant administrations. On the other side of the aisle, Half Breeds supported none other than James G. Blaine for the Republican presidential nomination. The personal hatred between Conkling and Blaine, dating back to their early service together in the House of Representatives during the Civil War, made the issue that much more heated and complicated.

wikipedia.com

At the Republican convention in Chicago, Half Breeds worked tirelessly and successfully to block Grant’s nomination. In turn, the Stalwarts gave absolutely no consideration to supporting Blaine. After the first several ballots, it was clear that neither man could obtain the necessary votes to capture the nomination. A compromise candidate was needed. James A. Garfield of Ohio, longtime member of the House of Representatives and currently Ohio’s Senator-elect, was liked and respected by members of both factions. Garfield had traveled to the convention to nominate another candidate Conkling and the Stalwarts would never support: Treasury Secretary John Sherman. On the 36th ballot, Garfield, still stunned that his name had been forwarded as a candidate at all, received the nomination. To appease the Stalwart faction, Conkling disciple Chester A. Arthur, just two years removed from his New York Customs House firing, received the party’s vice presidential nomination.

Garfield went on to defeat Democrat Winfield Scott Hancock by a razor-thin popular vote margin in the 1880 election and assumed the presidency on March 4, 1881. If the Arthur nomination was intended to be an olive branch to the Stalwarts, that branch cracked when Garfield made James Blaine his Secretary of State. The branch then splintered into a thousand pieces when the new president nominated William H. Robertson to be Collector of the Port of New York without consulting Conkling. Historian Heather Cox Richardson notes that Conkling was “a famously touchy character” and that he was “undoubtedly personally affronted.” However, as Richardson points out, Conkling opposed Robertson’s nomination by claiming that the Senate’s role to advise and consent to presidential appointments gave senators the power of appointment itself. “What was really at stake,” writes Richardson, “was whether or not Conkling would control New York.”

Conkling devised a bold plan to force the issue and embarrass President Garfield. He and New York’s other senator, Thomas Platt, resigned their seats in protest and fully confident that the New York legislature would immediately reappoint them. (Recall that at this point the people did not elect their senators; rather, they were chosen by state legislatures.) Conkling and Platt miscalculated; the New York legislature was happy to be rid of them and promptly elected others to fill their seats. The Senate confirmed Robertson as head of the New York Customs House, and James A. Garfield won the only political victory of his very brief term in the White House.

wikipedia.com

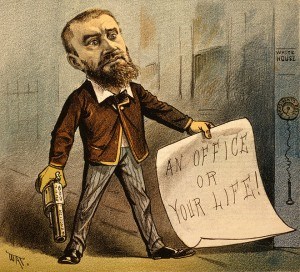

So what does any of this have to do with Charles Guiteau and his attack on Garfield? Guiteau considered himself to be a Stalwart Republican. He had supported U.S. Grant for the party’s nomination in 1880, even preparing a nonsensical speech he hoped to give for the Grant campaign throughout New York. When the Republicans ended up choosing Garfield instead, Guiteau simply crossed out all references to “Grant” in his speech’s text and replaced them with “Garfield.” During the campaign, Guiteau hounded Republican officials to let him give his speech, which he finally did to a small and puzzled crowd. This odd performance led the mentally unbalanced Guiteau to believe that he had helped Garfield win New York, the most coveted electoral prize of the 1880 contest and the state that put Garfield over the top and into the presidency. His contribution to the party’s victory entitled him, he felt, to a patronage position, and he soon went to Washington, D.C. to present himself for consideration for the American consulship to Paris. Of course, he had no skills, qualifications, or experience to warrant such a position, but lesser men had received prized jobs under the patronage system.

Once he got to Washington, Guiteau was sorely disappointed. His efforts to secure the Paris appointment failed, and he became a nuisance to the new administration. He aroused the ire of Secretary of State James Blaine, who at one point thundered at Guiteau, “Do not ask me about the Paris consulship ever again!” Once Guiteau realized that he would not get the position he wanted and that the Garfield administration was serious about scrapping the patronage system all together, he decided that “removing” Garfield was his best option. Making Chester A. Arthur president would not only save the country from a Half Breed Republican like Garfield, but would also, considering Arthur’s past affiliation with Roscoe Conkling, save the patronage system and quash civil service reform once and for all. As a nice by-product, Guiteau would also surely receive the Paris consulship from a grateful President Arthur.

wikipedia.com

Guiteau bought a pistol and stalked the President of the United States around Washington before finally shooting him on July 2, 1881. Garfield lingered for eighty days and suffered horrendous medical treatment before dying on September 19. Rather than being heralded as a hero for saving the Republican Party, Charles J. Guiteau was incarcerated, tried, and found guilty of murder. (In what was probably one of the most lucid statements he ever made, Guiteau, when accused of murdering Garfield during his trial, replied, “The doctors did that. I merely shot at him.”) Guiteau was hanged on June 30, 1882. He died a “disappointed office seeker,” to be sure, but to describe him as that and nothing more only tells part of the story. He was also a political assassin that killed President Garfield in an attempt to force the Republicans to change course on civil service reform. The Republican Party’s factionalism, clearly responsible for the selection of Garfield as its standard bearer in 1880, also led to the president’s murder at Guiteau’s hands.

Written by Todd Arrington, Chief of Interpretation and Education, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, November 2012 for the Garfield Observer.