Last updated: August 7, 2021

Article

St. Luke Penny Savings Bank

Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site

"First we need a savings bank. Let us put our moneys together; let us use our moneys; let us put our money out at usury among ourselves, and reap the benefit ourselves. Let us have a bank that will take the nickels and turn them into dollars."

|

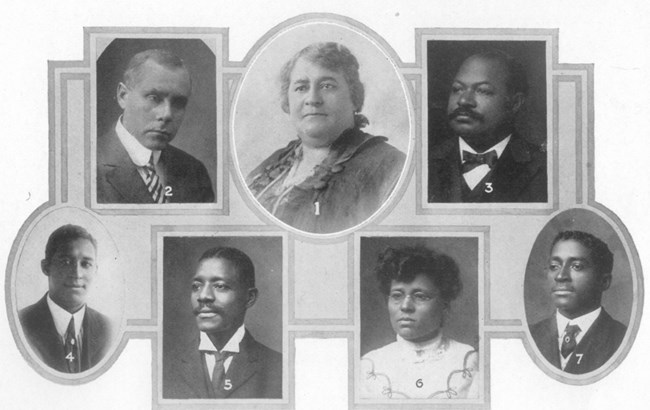

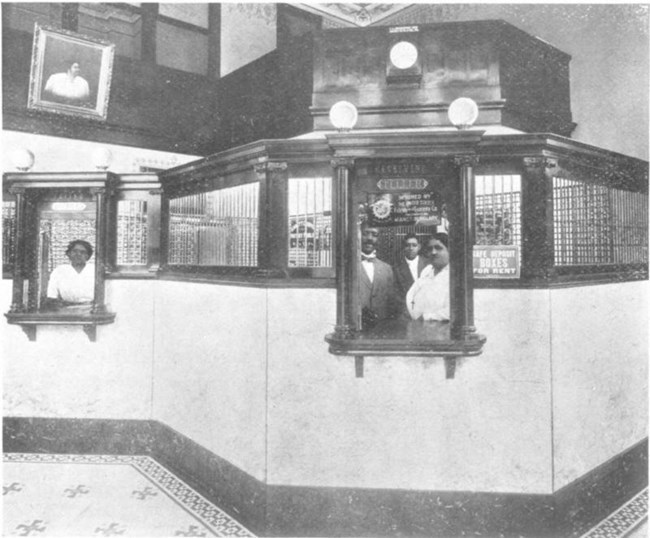

-Maggie L. Walker Beginnings of the BankAt the 1901 annual convention of the Independent Order of St. Luke (IOSL), Maggie Walker laid out her goals for her organization, including the formation of a bank, an emporium, a newspaper, and a factory. Of these objectives, the creation of a bank was foremost in her mind. Banks represented the pinnacle of financial achievement to many people. To Walker, a bank would combat the oppressive conditions of racial segregation while encouraging economic independence and thrift in the black community. Relegated to second-class citizenship, African Americans were denied rights in all aspects of life: education, employment, politics, and business. Walker's bank, along with other black-owned businesses, provided spaces to conduct business away from the racism and harsh treatment often found in white-owned businesses. Mrs. Walker's idea for a bank was not new. Several fraternal orders also opened banks in turn-of-the-century Richmond, including the Grand Fountain of the United Order of the True Reformers. Led by William Washington Browne, the True Reformers became one of the largest African American fraternal and business orders in America. In March of 1888, the True Reformers made history by receiving the first charter granted to African Americans to open a bank. Between 1888 and 1920, five other black-owned banks opened in Richmond, including Walker's St. Luke Penny Savings Bank and the Mechanics Savings Bank, which served as the main depository for another fraternal order, the Knights of Pythias. Numerous reasons compelled African Americans to open and patronize banks within their own community. Racial stereotypes discouraged many white bankers from loaning money to African Americans, fearing that loans would never be repaid. If black customers were issued loans, they were often charged a higher rate of interest than white customers. While many white-owned banks accepted deposits from black customers, some did not. These white bank managers feared that black customers would scare away white patrons. Mrs. Walker understood that using white-owned banks in such an environment merely served to "feed the lion of prejudice." By patronizing black-owned banks, African Americans in Richmond kept money in their own community and gained economic empowerment. While Maggie Walker first announced her vision of a bank in 1901, it would take over two years to see the dream realized. During that time, the Independent Order of St. Luke focused on recruiting new members, financing and building a new headquarters, and publishing the St. Luke Herald. The bank, however, was never far from Mrs. Walker's mind. St. Luke attorney James Hayes drew up the charter, which was approved by Virginia's Corporation Commission on July 28, 1903. Local newspapers carried the story, many noting the distinction that the bank would be led by an African American woman. Walker's notoriety grew when the Virginia Banker's Association extended membership to her. This offer had not been extended to any of the other presidents of the black-owned banks in Richmond. She accepted the invitation and remarked, "I shall hope to conduct myself so as to reflect credit upon my race and people." As the plans came together, Walker used the network of St. Luke councils to promote the bank. At the annual IOSL convention in August of 1903, she encouraged each council to open an account and buy bank stock. She also urged each individual member to open an account. Walker realized that if the bank was to succeed she would need the full support of her fraternal community. The Executive Committee of the IOSL served as the initial Board of Directors for the bank. At the first board meeting held on August 19, 1903, the group set an opening date for the business, sold 200 shares of stock to the Grand Council of the IOSL, and decided that most stock would be sold only to IOSL members. At another meeting, held on August 21, the board approved the hiring of clerks and set their salaries. The board appointed Emmett C. Burke as cashier at a salary of $50 per month, Mary Dawson as assistant cashier at $25 per month, and Maggie Walker as president, earning $25 a week for her work. To prepare herself for the position, Walker spent two hours a day at the white-owned Merchants National Bank of Richmond, studying procedures and operations of the bank. On November 2, 1903, the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank opened for business at the St. Luke Headquarters Building at 900 St. James Street. While music played and speeches were given, nearly 300 eager customers, many of them members of the IOSL, waited patiently to open bank accounts. While some people deposited more than one hundred dollars, others started accounts with just a few dollars, including one person who deposited just 31 cents. At the end of the day, the bank had 280 deposits, totaling over $8,000, and sold $1,247.00 worth of stock, bringing the total to $9,340.44. Mrs. Walker originally hoped for deposits exceeding $75,000, but she was pleased with the first day's success. At the same time, she recognized the hard work ahead to find success and security for the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank.

Maggie L Walker National Historic Site

The Bank Expansions and SuccessesIn an attempt to encourage deposits by children, Walker distributed penny banks among St. Luke families. Walker hoped the banks would teach children how to save their money and learn the importance of thrift. Once children had one hundred pennies in their bank, they could open an account at the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank. As a shrewd businesswoman, Walker also realized that every penny counted and that each deposit opened by a child would help strengthen the bank. To further the success of the bank and expand the empire of the IOSL, Walker recommended that the bank's Board of Directors purchase a building to house a department store and the bank. The vision of an emporium, run by African American women, was first vocalized by Walker in 1901, at the same time she announced her dream for the bank and the St. Luke Herald. As the bank slowly prospered, the time seemed ripe for the IOSL to further its influence in Richmond. In September 1904, the IOSL purchased a building at 112 Broad Street to house the St. Luke Emporium and the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank. The bank moved to this new location in October 1905. The bank would continue to grow steadily at this location. The year 1910 brought many changes not only to the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank, but banks throughout the state. The Virginia General Assembly added legislation that required all state banks to be examined annually by the State Corporation Committee. This law resulted in the closure of a number of banks across the state. The St. Luke Penny Savings Bank, however, successfully passed the examination and continued to operate. One bank not so fortunate was the True Reformers Bank. The Corporation Committee ordered the closure of the bank in October of 1910. Unsecured loans, lax operations, and embezzlement by a clerk led to its downfall, with most depositors losing their savings. The fall of the first black-owned bank in Richmond shattered the confidence of African Americans in the city. The Merging of Ideas to Survive Difficult TimesIn 1929, Walker met with officers and directors for the Second Street Savings Bank and the Commercial Bank and Trust to discuss a merger. While the Commercial Bank dropped out of discussions, the two remaining banks adopted a resolution to merge. The new institution, the Consolidated Bank and Trust opened for business on January 2, 1930 at the 1st and Marshall Street location of the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank. Still facing financial troubles, Commercial Bank and Trust merged with Consolidated in 1931. Walker served as Chairman to the Board of Directors for Consolidated Bank and Trust, a position she would hold until her death in 1934. While many banks did not survive the Great Depression, Consolidated Bank and Trust not only survived but thrived into the twenty-first century. In 2005, Abigail Adams National Bank purchased Consolidated Bank and Trust, ending Consolidated's distinction as a black-run, independently-owned bank. It is believed to have been the oldest continuously black-owned bank in the country until then. In 2009, Premiere Bank merged with Abigail Adams. Two years later, Consolidated Bank and Trust was renamed Premiere Bank. It still operates today at the corner of 1st and Marshall Streets. During its long history, the bank founded by Maggie Walker benefited the African American community in Richmond. By 1920, for example, it had issued more than 600 mortgages to black families, allowing many to realize the dream of home ownership. It provided employment for African Americans, giving some a chance to leave the menial, labor intensive jobs to which African Americans were often relegated. More than anything, the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank-turned-Consolidated Bank and Trust was a source of pride for black Richmonders. The bank served as a reminder of the lasting impact that Maggie Walker's vision and perseverance had on an entire community. |