Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

St. Louis’ Mid-Century Modern Architecture: The Matter of Materials

National Park Service

Defining Mid-Century Modern

Mary Reid Brunstrom: Thank you, Mary. I want to say thank you to the National Park Service and the sponsors of today for the opportunity to be on this program.

I might just say I'm speaking a lot more broadly than my religious dissertation topic today. I want to just start off by drawing your attention to two sources on mid century modernism in St. Louis.

One is the book on your right edited by Eric Mumford, Modern Architecture in St. Louis, and the other is an online thematic survey by Betsy Bradley of the Cultural Resources office of the city of St. Louis.

Mary Reid Brunstrom, Washington University

I have found both of these resources extremely valuable in my own work.

There's more mid century architecture in St. Louis in a rich array of types than most people realize, and I suspect that this is the case in most cities across the country.

We generally use the term mid century to differentiate the buildings of the post World War II years from the output of the pre-War years.

Mid century is an interesting term. It links architecture in the US to the growth and change resulting from post-War power and prosperity, even as the geo politics of the Cold War cast a haze of uncertainty over the period.

Like everything else at mid century, architecture was shaped by these conditions.

Mary Reid Brunstrom, Washington University

A Coherent Chapter in the History of Architecture?

Modernism went mainstream at mid century thanks to mass production and marketing of materials, systems, furniture, appliances, all the components of modern living. Here are some questions: What defines the new architecture of the period? Does it merit a stand alone label, mid century modern, to differentiate it within the broader frame of modernism? Moreover, does the period hold together as a coherent chapter in the history of architecture?

The vitality and originality of architecture in the post War years in St. Louis is due in no small measure to the vision and talent of architects who were based here, many of them associated with Washington University's School of Architecture. There appears also to have existed a climate of experimentation among architects in St. Louis in the 1940's and 50's. One, moreover, that engaged a number of gifted architects from elsewhere including Erich Mendelsohn, Buckminster Fuller, Minoru Yamasaki, and Eero Saarinen. With these premises and questions in mind, I offer an overview, a brief overview of the region's modernist buildings, showing how modernist thinking was pervasive in the building culture in both public and private sectors.

Since our symposium is organized around materials and preservation, I highlight buildings in which materials were key to new architectural solutions. I also trace a narrative of loss, because, like other parts of the country, as we've heard from our keynote speaker, and indeed the world, many landmarks of modernism in St. Louis are under threat of demolition or are already lost.

Mary Reid Brunstrom, Washington University

Brick, Tera Cotta, and the Modern Steel Skeleton

St. Louis' modernist architectural narrative is one of continuity and innovation, especially with respect to the use of brick. Nowhere is the persistence of brick as visible as in the robust, elegant and ordered, brutalism-inspired façade of St. Louis Community College at Forest Park, 1965, designed by the Chicago based architect Harry Reese and associates. The brick construction in the region is an extrusion of its geology, literally a man made formation on the surface that expresses the layers of clay beneath. Local abundance made clay products, the material for high and low cost architecture alike.

Brick and terra cotta were vital components of the 1891 Wainwright building which established St. Louis as a site where the challenges of modern tall building were triumphantly addressed. Designed by Adler and Sullivan, the Wainwright demonstrates mastery of brick and terra cotta applied over a modern steel skeleton.

Mary Reid Brunstrom, Washington University

Further north, the Neighborhood Gardens apartment complex was completed in 1935 as a settlement home for white working class, typically immigrant families who worked in the downtown garment industry nearby. Designed by Hoener, Baum and Froese, the patenting and craftsmanship recall the use of brick in modernist housing developments in Holland during the period. Here, the architect gave St. Louis' accomplished brick layers artistic freedom, resulting in rich surface textures.

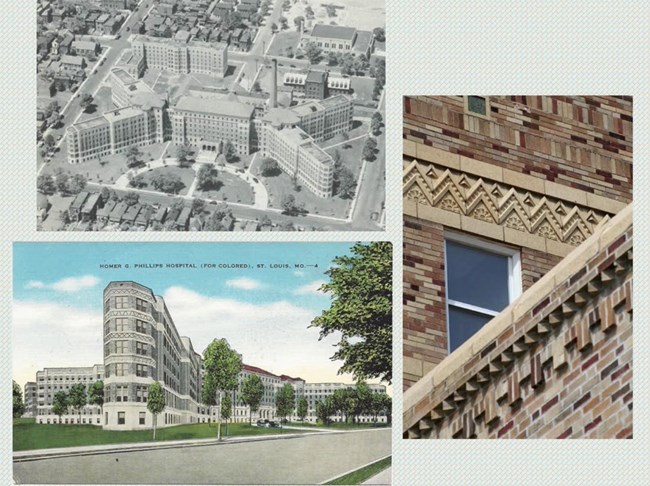

Also in the mid 1930's, the Homer G. Phillips Hospital, a medical complex designed to serve black health care needs in a segregated St. Louis, arose in the Ville neighborhood to the north. Designed by city architect Albert Ausburg, the complex was hailed for it's sensitive accommodation to the surrounding residential architecture. Achieved in part by the disposition of the brick in horizontal courses that helped to ground the structures. The complex exemplified how the beauty of materials could be leveraged to turn a monolithic institutional presence into an aesthetically pleasing community attribute.

Mary Reid Brunstrom, Washington University

Frank Lloyd Wright

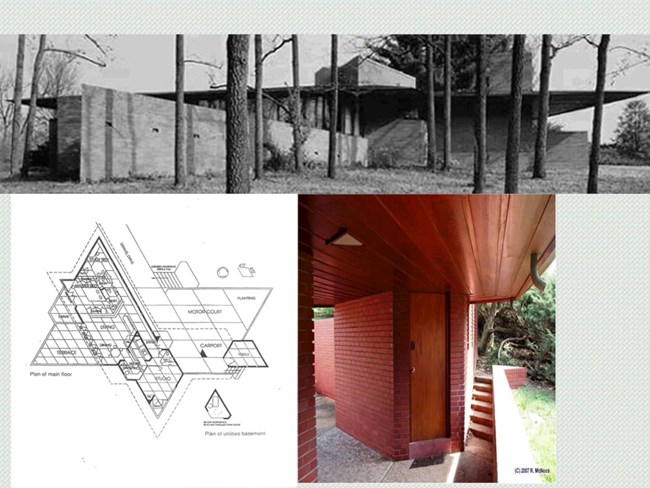

Frank Lloyd Wright designed two houses in St. Louis, both notable for their coherent brink elaboration and we'll look at one of them. The plan of the 1951 craft house is based on an equilateral parallelogram module that is repeated throughout the building in a variety of scales, on the slab floor, and in the Wright-designed furniture. The warmth of the craft house arises from its two signature materials, tidewater red cypress and Wyandot brick which Wright continued from the exterior to the interior.

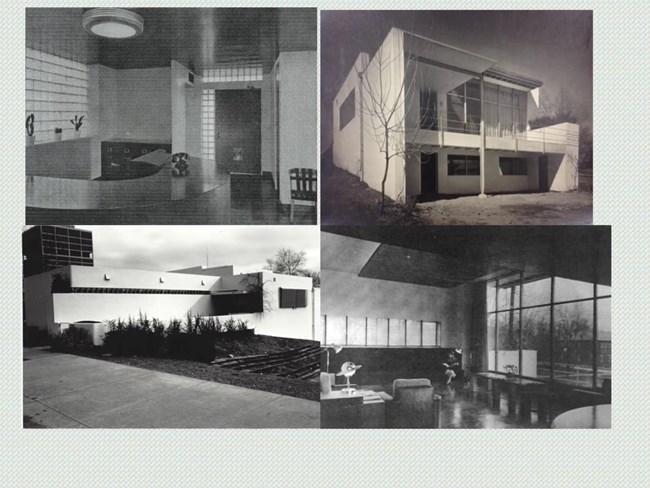

Wright's organic design principles were taken up by William Bernoudy, who had learned from Wright firsthand as a fellow at Taliesein. In St. Louis, Bernoudy worked in partnership with Ed Mutro, to be joined later by Hank Bauer. All told, the Bernoudy partnerships built an extensive inventory of houses using brick and wood that translated Wright's ideas into comfortable, livable environments mostly for the well-to-do. Bernoudy's own home in Ladue — shown here — is an exquisite essay in residential modernism.

Mary Reid Brunstrom, Washington University

B'Nai Amoona Synagogue & Architectural Experimentation

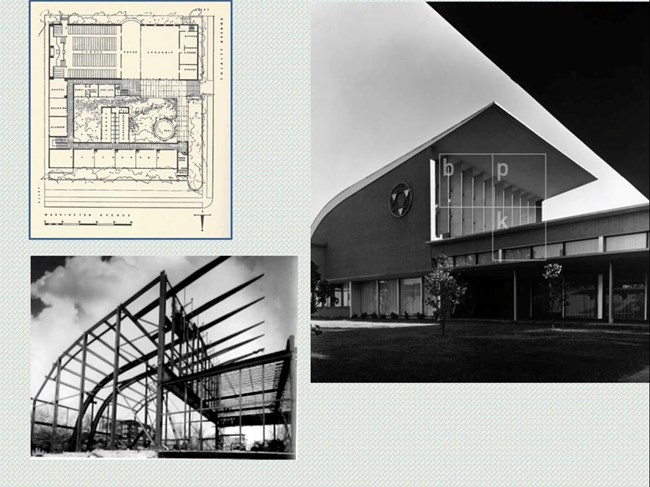

B'Nai Amoona Synagogue built from 1945 to 1950 was the first US commission for the German emigrate Erich Mendelsohn. Mendelsohn's work in St. Louis was significant for the city's standing a venue for architectural experimentation.

B'Nai Amoona was the first modern synagogue in North America. As such, it ushered in a period of reinvention of synagogue design across the country. B'Nai Amoona is constructed of concrete block faced with buffed Ohio brick set in a stacked on pattern.

The lightness of the color mediates the sense of weight and the geometric ordering results in a certain quietness in the masonry that seeds the drama of the design to its signature feature, namely the sweeping roof the cantilevers out from the sanctuary wall.

Mendelsohn enlivened his predominantly flat-roofed horizontal scheme — seen here in plan — with the wing-like of a bisected parabola. A daring tectonic gesture writ large against the sky to dramatize modernity.

The soaring curve that projects some 26 feet from the wall was formed with steel I-beams that taper from the base to the termination of the cantilever.

Mary Reid Brunstrom, Washington University

Structural Concrete & Reinforced Concrete Shell Technology

In the post war years as structural concrete began to enter the mainstream, reinforced concrete shell technology opened up seemingly unlimited possibilities for architects who exploited its plastic qualities to produce some of St. Louis' most remarkable buildings.

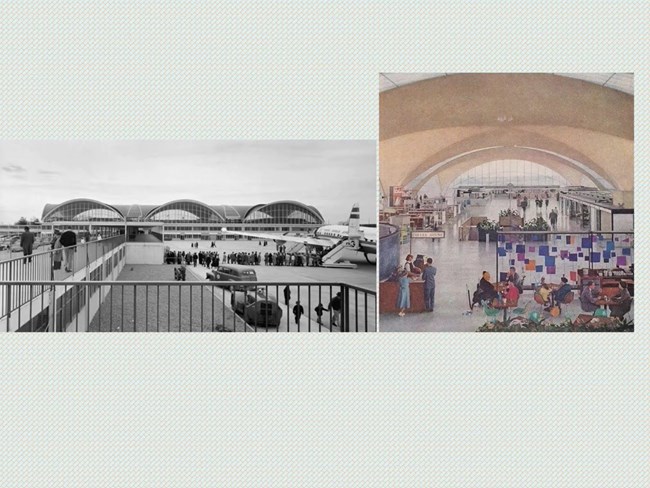

Helmeth, Yamasaki, and Linewibers Lambert International Airport terminal, which opened in 1956 and which Theo Abata has described for us this morning, featured a series of three intersecting parabolic vaults enclosing the passenger check in and waiting areas.

On the interior, a 48-foot long metal partition screen, crafted from brightly colored geometric shapes by Cranbrook-trained sculptor Harry Bertoia, underscored the modern vocabulary of the terminal design.

Mary Reid Brunstrom, Washington University

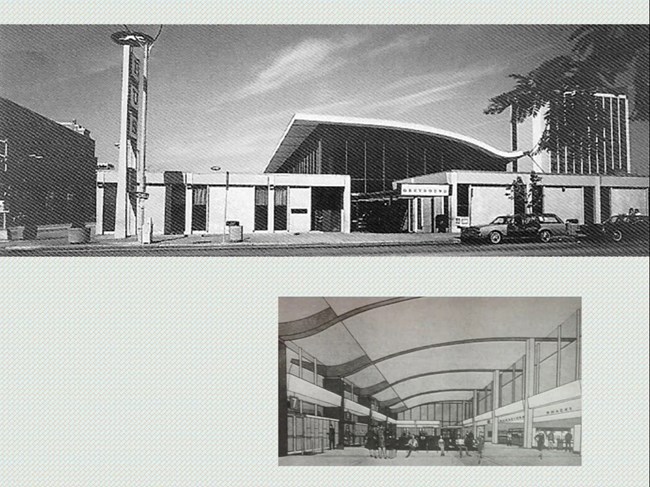

An alternative gateway, one for bus travelers, arose in 1964 on Broadway in Downtown St. Louis.

Schwartz and Van Houfen’s design for the Greyhound bus terminal also deployed thin-shelled concrete for a parabola based roof that cantilevered over the passenger terminal in a dynamic, swooping gesture evocative of the dynamics of travel.

This mode of mid century design was demolished in 1992.

However, a more positive outcome was achieved for the former Phillips 66 station in midtown known colloquially as the flying saucer or the Del Taco building.

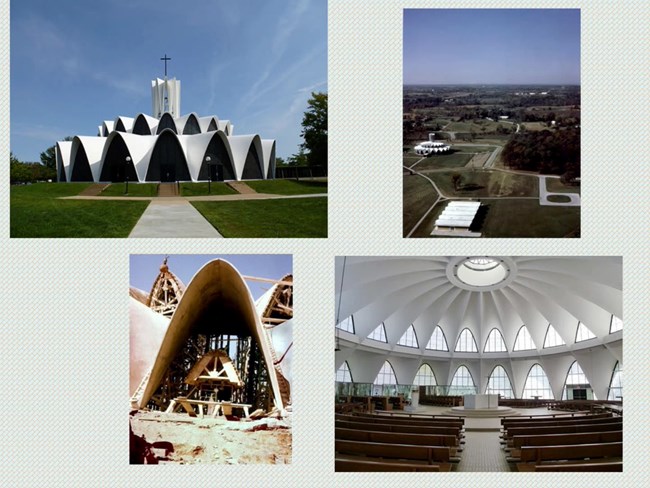

In 1956, as design partner in the newly formed Hellmuth, Obata, and Kassabaum, Gyo Obata started design on the Priory Church for the Catholic order of Benedictines.

This was the firms first religious commission.

Mary Reid Brunstrom, Washington University

The client believed in the potential of a new architecture to shape modern Catholic faith, and as we have heard from one our participants, that potential he had glimpsed in the light-filled, airy structure of Lambert airport and in which thin-shelled concrete played the starring role as a material.

Gyo Obata effectively reformulated the medieval arch in thin-shelled concrete as a parabolic form thereby embedding layers of reference for the Benedictines whose normative building style was Gothic revival.

Instead of glass, Obata used Kalwall for the windows, in insulated, reinforced, fiberglass product that appears black on the exterior but admits a suffused light to the interior.

Mary Reid Brunstrom, Washington University

New Era of Retailing

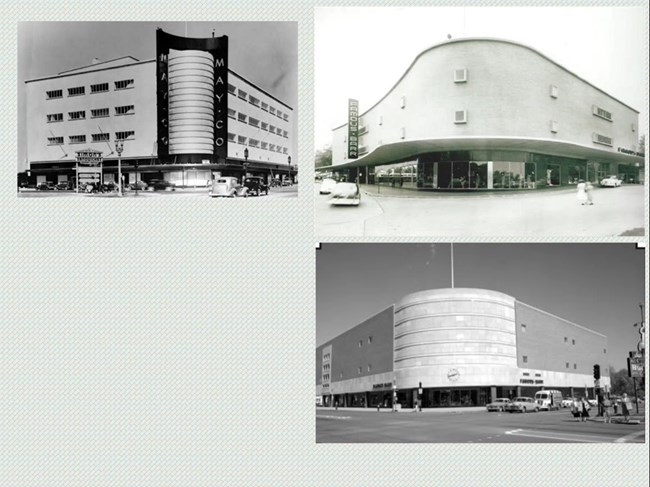

In the secular sector, the May Company, a national St. Louis based retailer headed by Morton May, introduced a new era of retailing with three new branches of its famous bath store.

The Clayton Famous, which opened in 1948, — seen in the middle image — was designed by Samuel Marx with his Chicago-based firm of Marx, Flint and Shone. The store and the Southtown famous designed by John P. Herner to resemble it's Clayton sibling repeated the signifying features of the May Company's ultra modern Los Angeles store on Wilshire Boulevard Miracle Mile, on the left here, including the flat roof, the streamlined corner on the building's leading edge, and the continuous band of display windows at the street level.

Earlier May had made exclusive his commitment to modernism when in 1940 he commissioned Marx to design an international style residence for him in Ladue, a landmark that was demolished in 2005.

The third famous bath store was built as the anchor of Northland Shopping Center introducing one-stop suburban shopping, a concept that integrated a department store on site with other retailers and amenities. Designed for the May Company in 1955, Northlands was composed of cubic volumes of varying heights articulated by open walkways on a 50 acre site that accommodated the increasing demand for parking. Construction costs were reduced with the use of a welded steel frame, one of the first such applications in a multistory project in the area.

In nearby Welston in 1948, a distinctive store based on international style concepts was designed for J.C. Penney by the father and son team of William P. and Bernard McMann. Faced in smooth white stucco incised with a regular grid relieved by rows of thin metal sash windows, the store sported an open roof deck reminiscent of of LeCorbusier’s Villa Savoye near Paris. The building has been unoccupied for some four decades.

Mary Reid Brunstrom, Washington University

The Arch as a Signature Parabolic Motif

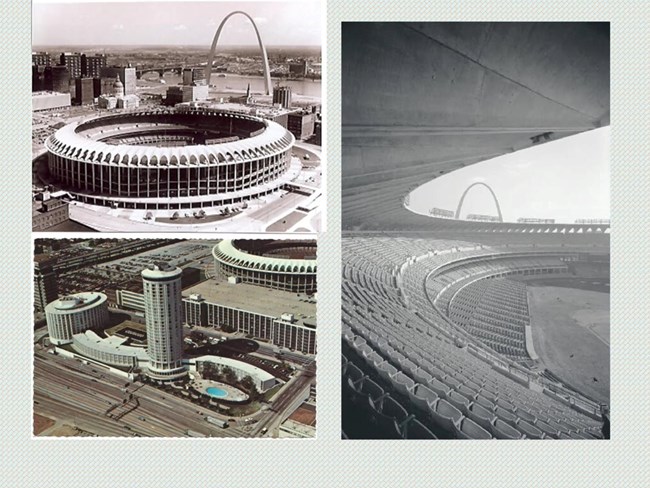

We have heard about the McDonald planetarium. Busch Memorial Stadium, which opened in 1966 as the new home of the St. Louis baseball Cardinals and was demolished in 2005, was part of the logic of the modernized river front and formerly very much at peace with the Gateway Arch from which it took its signature parabolic motif.

Designed by Edward Durell Stone, the stadium's graceful coronative parabolas as the roof life realized in concrete exclusive acknowledged Saarinen's arch.

In 1960, Washington University unveiled a modernistic departure from the campus's collegiate Gothic style with Steinberg Hall, which was the first commissioned in the United States with the Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki, who was working at Washington University School of Architecture at the time. Steinberg Hall exemplified the potential of thin-shelled concrete with a distinctive roof that remains a definitive essay in folded plate structure.

Mary Reid Brunstrom, Washington University

Physicians and related professionals were really proponents of the modernist design both for its efficiency and relative economy and because of what the new architecture could represent to a public emerging from the strictures of the depression, namely a confident, optimistic, future oriented approach to medicine.

No where is this more evident than in the orthodontic clinic that Harris Armstrong designed in 1935 for Dr. Leo Shanley in the future County Business District of Clayton.

A pristine white building on a prominent corner site, the Shanley Building is recognized as the first foray into the international style in the area.

The building is made from poured concrete and covered with a skin of fine white stucco.

Mary Reid Brunstrom, Washington University

Suburban Homes: Modern Middle-Class House

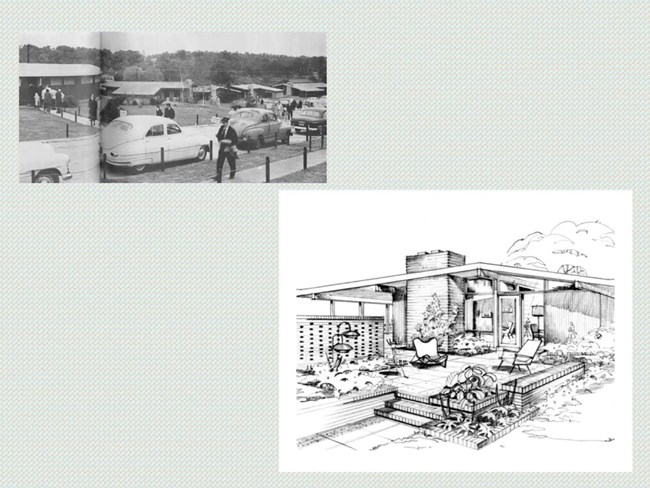

Returning war veterans created the demand for new housing that was met by suburban expansion in all directions from St. Louis and made viable through increased car ownership. The ranch houses was the dwelling type of choice for the middle class family. In the St. Louis region, the developed Burton Dankey realized early that money could be made using mass production with its economies of scale to address the challenge of affordability.

While large houses for the wealthy were literally spacious in terms of size, area, and volume, the sense or illusion of space in a structure that was physically much smaller than it seemed or felt became an indispensable feature of the modern middle class house.

The Washington University trained team of husband and wife architects Ralph and Mary Jane Fournier, who became collaborators in the realization of Dankey's vision, had a deft talent for creating spaciousness in their architecture. The prototypical house designed for Ridgewood in 1952, one of Dankey's five subdivisions in the area, featured a slab on grade foundation with post and beam construction and open interiors.

Prefabricated wall panels manufactured locally by Dankey's company were shipped within a 550 mile radius of St. Louis.St. Louis seemed progressive at least to the editor of House and Home, who in 1953 observed that conservative St. Louis buyers were part of a national trend toward modernist housing and predicted that the Dankey-Fournier models would be implemented across the country by them and by others following suit.

Mary Reid Brunstrom, Washington University

Modular Technologies

A novel modular wall system was introduced by Ed Mutro working in partnership with William Bernoudy for the interior and exterior of his 1950 house in Ladue. Demolished in 2005, the Mutro house featured walls of fire resistant cemesto board, which the Celtex Corporation had introduced in 1937 for heat and sound insulation.

Asbestos cement was applied to one or both sides of the panels, which in Mutro's house, were then painted and mounted in wood frames. A noticeable less aesthetically mediated application of Celtex panels could be found in the residential architecture of Isador Shank. Shank used structural insulation panels with exposed bare beams which enhanced the solid look and feel of the house.

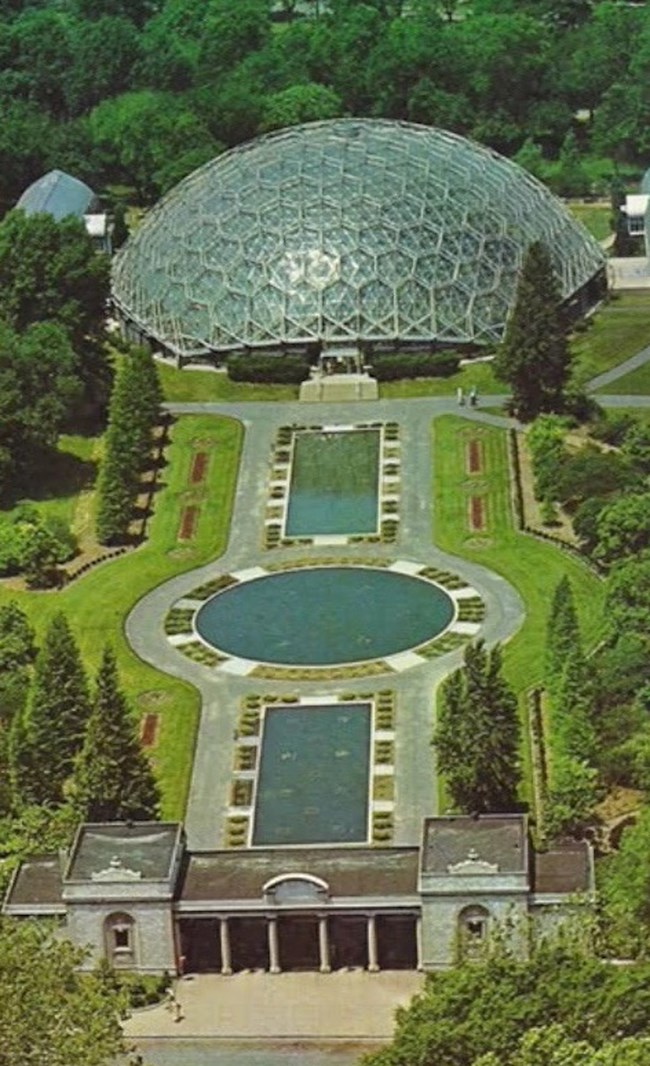

Opening in 1960 and based on modular technology, the Climatron at Missouri Botanical Garden was the first application of Buckminster Fuller's geodesic dome concept to a greenhouse. The form encapsulated institution's scientific mission and was readily associated with technological progress. Murphy and Mackey were the architects.

The dome, designed by Synergtics, constituted a grid of structural triangles over a sphere and was, according to Fuller, the most efficient way to enclose space using minimal material. The dome was fashioned from triangular Plexiglass panels suspended from an aluminum frame and sealed by neoprene gaskets. This system pioneered the use of aluminum as a structural metal. A feat that earned Murphy and Mackey the 1961 R. S. Reynolds Memorial prize for innovative use of aluminum.

Mary Reid Brunstrom, Washington University

High Rise Apartments

In the 1950s, as downtown St. Louis declined, redevelopment initiatives in the 1947 city plan drawn up by the architect and planner Harland Bartholomew went into effect. Plaza Square, a complex that integrated six modern apartment blocks of limestone, brick, and concrete with two historic churches on a four block site tested the premise that a blighted downtown precinct could be reinvented with modern, market-rate, high-rise housing that would attract residents back to the urban core.

For the project, the newly formed HOK teamed up with Harris Armstrong. The unique color field of enamel painting on the east and west walls of the towers were specified by Alexander Girard, who had worked with Eero Saarinen on the General Motors technical center in Detroit and the Miller residence in Columbus, Indiana.

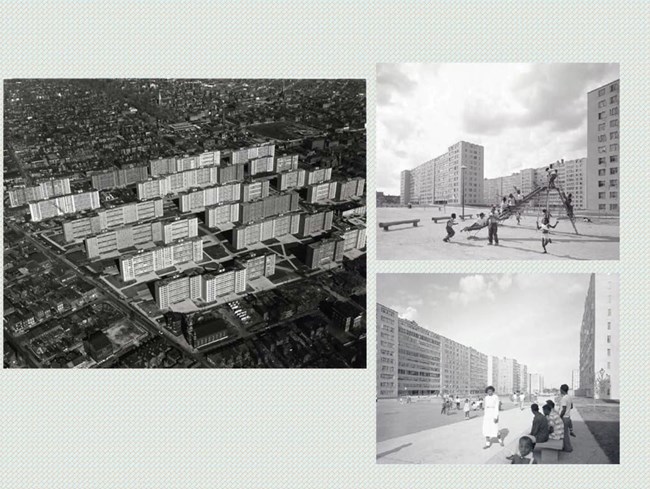

You will of course recognize this as Pruitt-Igoe, which was demolished in the 1970s. From 1950 to 1956, the city of St. Louis erected public housing on a hither to unprecedented scale in the US, and Pruitt-Igoe was the largest such project in the region. It consisted of 33 flat-roof, concrete slab highrises faced with brick with walls punctuated by glazed galleries and middle sized windows.

The architect Minoru Yamasaki of Hellmuth. Yamasaki and Lineweber, who would design Lambert Airport and later the World Trade Center in New York City, drew his modernist urban planning inspiration from the Le Corbusier who advocated some clearance in a tabula rasa. When the implosion started in 1972, Pruitt-Igoe came to associate St. Louis with a failed public housing experiment and moreover with the demise of European style modernism itself.

Mary Reid Brunstrom, Washington University

Innovative and Extensive Use of Glass

From the late 1930s onward, innovative and extensive use of glass marked many new building as modern and we'll look at just one application of this. In 1947, Harris Armstrong designed a headquarters and display center for the American Stove Company, later Magic Chef, a building that was praised for its strategic use of day lighting through bands windows running the length of the north and south facades.

Armstrong embedded Magic Chef's marketing strategy into a modern state of the art building with glass expanses that allowed the building to glow at night in a perpetual advertising cycle. The retail experience unfolded in a facility replete with vital forms including a artful play of biomorphic shapes on the ceiling of the entry lobby by the sculptor Isamu Noguchi, which involved a lunar landscape.

Stained glass is a feature of the Lewis and Clark Branch Library in North County designed by Frederick Dunn and Nolan Stinson. Dunn and Robert Harmon of the Emil Frei Studio produced a dazzling display of glass on the north façade that integrated figurative representations of the legendary explorers with fields of saturated primary colors and textured panes of abstraction. This modernist landmark is under a demolition order as we speak. Part of the glass with be displayed in the new building.

Mary Reid Brunstrom, Washington University

Gateway Arch

In conclusion, I turn to the Gateway Arch which is the centerpiece of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial here on the Mississippi river front and the indispensable symbol by which people everywhere identify St. Louis.

Eero Saarinen's pitch perfect, stainless steel expression of the times rises from a complimentary landscape of biomorphic shaped water features set in greenspace and designed with the landscape architect Dan Kiley.

Saarinen in search of a form whose simplicity would render it simultaneously timeless and magical in the moment started out with a parabolic concept in mind. A parabola is an open form with the central axis and arms diverging symmetrically on both sides from the vertex. Saarinen was familiar with parabolic form, and I won't elaborate on this but I could later. The arch ended up being catenary not a parabola.

As this compendium shows the incidence of parabolic form in the post war years in St. Louis is striking. The architects of these buildings embraced formal innovation using materials such as thin-shelled concrete and structural steel even as brick was revitalized a building material of choice.

The result has been a trove of unique structures which attests to a spirit of inventiveness in the period. Because of historic and mid century modern structures are sadly gone, the loss of any one of those remaining should give us pause.

Thank you.

Speaker Biography

Mary Reid Brunstrom is an architectural historian completing a PhD at Washington University in St. Louis. Her field is architectural modernism and her topic investigates the churches designed from 1947-1954 by Murphy and Mackey for the Catholic Archdiocese of St. Louis. Her dissertation identifies a climate of experimentation among architects in the region, a climate enhanced by the activity of influential outsiders such as Eric Mendelsohn and Eliel and Eero Saarinen, and one in which form and materials emerge as compelling themes.

Brunstrom holds two master’s degrees from Washington University, one in liberal arts with a thesis on Richard Serra’s sculpture “Twain” in Downtown St. Louis, and the other in art history with a thesis entitled “Modern in St. Louis: Modernist Architects and Their Clients.” She presented a talk entitled “Land Clearance and Reinvention of the St. Louis Riverfront” in Washington University’s 2009 international symposium On the Riverfront: The Gateway Arch and St. Louis. Recently, she presented a published paper at an international symposium entitled “‘Le Jeu Savant:’ Light and Darkness in 20th Century Architecture” at the Accademia di architettura in Mendrisio, Switzerland.

This presentation is part of the Mid-Century Modern Structures: Materials and Preservation Symposium, April 14-16, 2015, St. Louis, Missouri. Visit the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training to learn more about topics in preservation technology.