Last updated: September 26, 2025

Article

Southern Claims Commission

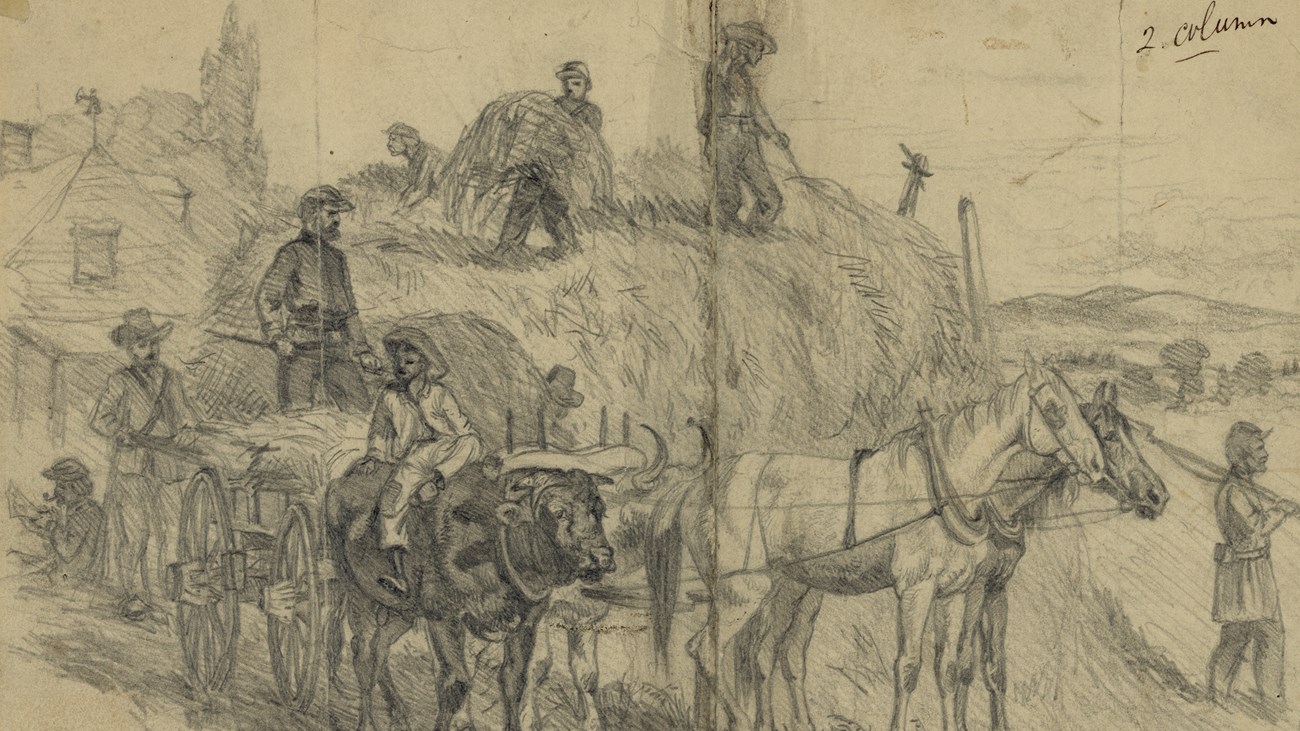

Courtesy of Library of Congress

Home Front to Front Lines

As the Shenandoah Valley endured so much movement of armies throughout the war, few communities suffered as much loss as here. From 1862 to 1865, there was almost always one army encamped there. In both 1862 and 1864 residents were in the middle of large campaigns.On March 3, 1871, Congress created the Southern Claims Commission. The Commission could review claims and recommend them to Congress for payment, or not. Claimants, regardless of their race or gender, had the ability to compile lists of property lost during the war and provide testimony and witnesses to support the claim.

To receive payment, claimants needed to prove they owned the property, that United States soldiers (not Confederates) took the property, and the property was used for official purposes. Finally, they had to prove that they were loyal to the United States throughout the war. Claimants often proved this by showing they helped Federal soldiers evade capture, fed them, had not voted for secession, or were threatened by neighbors and local officials for their support of the Union.

Claims Near Middletown

Park staff have compiled dozens of records of civilians who lived in and around Cedar Creek and Belle Grove National Historical Park that applied for repayment. Some were successful, and some were not. Some had very detailed records of what regiments or officers were camped on their property on specific dates, and some did not. Many of these claims were approved, and they received hundreds of dollars in repayment. However, some claims were denied while some that were approved were not paid until 1880 or even later after continued cases in the Court of Claims. Even the quickest payment was long after the property had been taken.Local residents said that United States soldiers had taken a variety of property for army use. Sometimes it was hay, corn, or wheat to feed the military horses. Sometimes it was horses themselves, taken for army service. Other times it was cattle, sheep, hogs, bacon, apples, or flour that was eaten by soldiers when they had little food.

There are many powerful stories that can be found within these pages, attesting both to Unionists in the Shenandoah Valley as well as the personal cost paid by civilians during the war:

Dr. Henry Shipley rented a farm near Middletown that would be caught in the middle of the Battle of Cedar Creek. Despite threats as Confederate soldiers swarmed his property, Shipley hid and treated Union soldiers wounded during the morning surprise attack. He received $1,105 for various property taken during the war.

Samuel Sonner ran a store in nearby Strasburg. His claim was denied, as the investigator found his name in a voter book as having voted in favor of secession. The Southern Claims Commission found his testimony and witnesses untrustworthy, and believed he was pro-secession until it became clear that the United States would win the war.

James Foster was enslaved during the war but worked extra hours as a skilled shoemaker to obtain property and support his free family. He helped Union soldiers escape capture, though the army took his horse, several hogs, and a cow from him during the war. When asked about his loyalty, he stated, “I sympathized with the Union cause all the time. I could not be any other way. I was a slave and I wanted to be free and was confident if the Union cause was successful I would be free; and my race too.”

Elizabeth Mummaw was a member of the pacifist United Brethren Church, sometimes known as the Dunkers. A widow, her husband Jacob had died after the war. Their daughter Alice testified that “he was always kind and allgiving to the northern soldiers and would do any-thing for them. They were fed at our house many times. My father had gone with them on several occasions to point out the way when in danger of being taken by the rebels.” Elizabeth claimed $468 for supplies taken from her, and received $268.

Farmer Jacob Hockman applied for $764 payment regarding horses, hay, corn, oats, hogs, and sheep. He was denied as he had often brought supplies to the Confederate army, voted for secession, and invested his money in Confederate bonds.