Last updated: January 9, 2024

Article

Songbirds of Minong: Monitoring at Isle Royale, 2014-2018

NPS photo

The National Park Service has monitored songbird populations on Isle Royale since 1994. The variety of habitats found in the islands provide nesting areas for 89 species of songbirds. Surveys are conducted in June during the first four hours of daylight. Observers spend five minutes at each of 130 survey points distributed along eight park trails including Passage Island.

Photos: W.H. Majoros/Wikimedia Commons, NPS photo, NPS/W. Greene-Friends of Acadia, USFWS/S. Maslowski

2014–2018

A recent analysis of data collected from 2014 through 2018 found four species with the densest populations on the island were heard or seen most often during surveys: Nashville Warbler, White-throated Sparrow, Winter Wren, and Ovenbird. However, among those four species, all but the White-throated Sparrow showed declining trends over the five-year period. The Nashville Warbler showed the greatest decline at 6 birds/mi2/year, but this was not statistically significant. The only stastically significant trend was that of Yellow-bellied Flycatcher, declining at a rate of almost 3 birds/mi2/year.

Among guilds (a group of species that share a common trait such as habitat type, nest location, or food source), there were three increasing density trends that were not stastically significant. However, four guilds showed significant declining trends: insectivores such as warblers and flycatchers (−2 birds/mi2/year), shrub/low canopy foragers such as the thrushes (−3 birds/mi2/year), successional/scrub species such as the flicker and chickadee (−5 birds/mi2/year), and woodland species, which is most of Isle Royale’s birds (−2 birds/mi2/year).

Photos: NPS/R.Hannawacker, NPS/K.Miller, N.Dubrow/Macaulay Library-CLO/NPS collection, USFWS/S. Maslowski.

What Will the Future Sound Like?

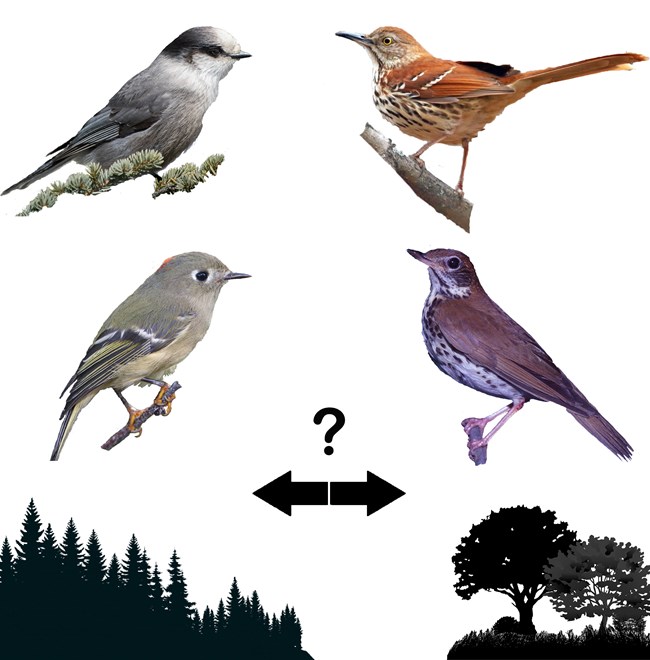

One study comparing bird population changes under two different climate scenarios predicted high turnover of species populations on Isle Royale by mid-century (2041–2070) if the nation continues on its current path of rising emissions1. They offer no predictions on the future of the island’s four most common species or even the Yellow-bellied Flycatcher, but some current summer residents are expected to fare worse under future climate conditions, including the American Robin, Least Flycatcher, Mourning Warbler, and Swamp Sparrow. The Gray Jay, an iconic boreal species, is predicted to disappear from Isle Royale in the summer, while species like the Wood Thrush and the Brown Thrasher may begin to colonize the island.It’s important to note that a changing climate is only one part of these possible changes. The habitat these birds depend on will have to shift as well. The Wood Thrush prefers a different kind of forest to the Swainson’s and Hermit Thrushes we find on the island now. And the Brown Thrasher prefers a drier, shrubbier landscape than is currently found on the island.

Change is certainly coming, but how much change remains to be seen. Birds will continue to fill the morning with song, but some of the performers may be new.