Last updated: December 23, 2021

Article

Soldier who served with two German regiments in the Union army buried at St. Paul’s

National Park Service

Soldier who served with two German-American regiments in the Union Army buried at St. Paul’s

A chapter in the experience of German immigrants in the Union army is captured through the biography of Henry Schlote, a Civil War veteran buried in the historic cemetery at St. Paul’s Church National Historic Site, in Mt. Vernon, New York.

Born in Hanover in 1826, Schlote immigrated to America in the late 1840s, joining thousands of refugees fleeing the German states following the failure of the revolutions of 1848. Often called “48ers,” these political exiles included many educated, middle class professionals and skilled tradesmen. Schlote’s pre-immigration profile is not clear, although in America he found employment in the building trades, carpentry and painting. In 1860, the unmarried immigrant lived as a border in a section of Mt. Vernon settled by Germans in the 1850s, near St. Paul’s Church, about 20 miles north of New York City.

Energized by President Lincoln’s April 1861 call for volunteers to subdue the rebellion in the South, Schlote was an early recruit for the Union army. The 35-year old immigrant traveled to Manhattan to join Company K of the 7th New York Volunteer Infantry, a regiment with a distinct German profile. Labeled the Steuben Guard, the unit recalled Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, the German general who helped develop the Continental Army during the American Revolution. Enlistment details record that Private Schlote stood at average height, 5’ 8”, with a fair complexion, brown hair and blue eyes.

The regiment experienced considerable combat in the Peninsula campaign of spring 1862 under General George McClellan, particularly at Malvern Hill on June 1, suffering 70 casualties. The Steuben guard also launched several charges at the Battle of Antietam in September 1862 and at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, where the New Yorkers absorbed more than 250 casualties. In late April 1863, the regiment returned to the city, mustering out in May following the proscribed two years of service.

Schlote was among an estimated 216,000 German immigrants in the Union army, or about 10-percent of the total force, the largest ethnic group in the Northern forces other than men born in the United States. Perhaps 300,000 additional men of German ancestry who were born here fought for the Union, or a total of 526,000, about a quarter of the entire armed forces that sustained the republic. This represents a contribution to the Union army roughly in proportion to the German percentage of the Northern population. New York and Ohio were particularly fertile grounds for the supply of those troops, with the Empire state fielding ten regiments consisting almost exclusively of German soldiers. Those units, including Schlote’s 7th New York, generated a recognizable and largely positive public image, although a majority of men of German descent enrolled in regiments that were not dominated by Germans.

Beyond a traditional motivation to demonstrate patriotism through bearing arms for their new country, many of the German 48ers embraced the antislavery impulse and supported the war as a strategy to achieve emancipation. Additionally, they recognized the cause of the survival of the American republic as a corollary to their struggles against authoritarian rule in Germany. Northern soldiers often cited the musical contribution of those troops, singing traditional German songs and American patriotic selections in balanced harmony, and assembling some of the Union’s finest bands. These German soldiers achieved admirable combat records and the 48ers, in particular, energized the artillery, engineer and signal units, the more highly skilled outfits of the army.

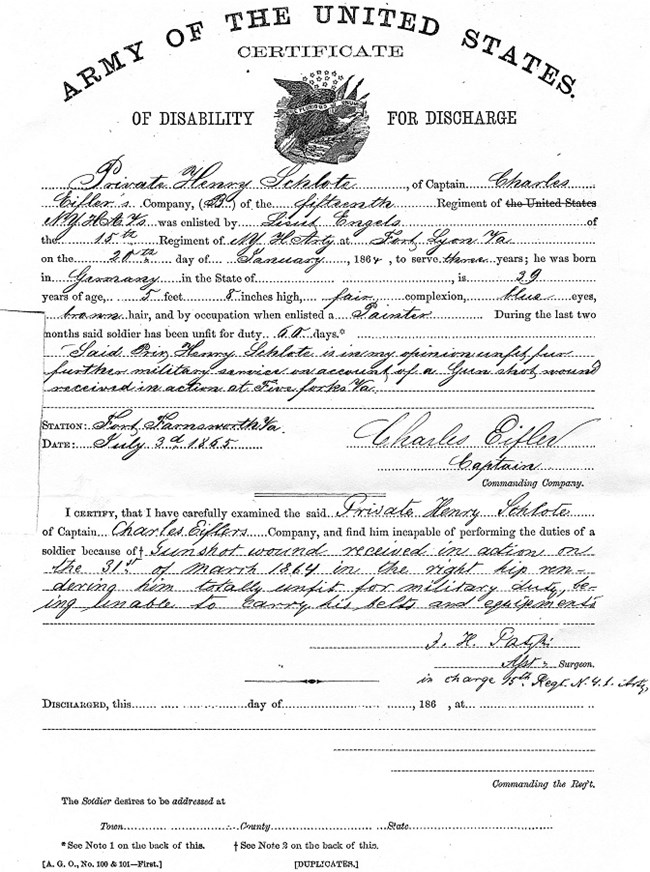

After an honorable discharge from the 7th New York, Schlote returned to Westchester County, but not for long, re-enlisting in January 1864 with Company B of the 15th New York Heavy Artillery, another unit with a German roster. Schlote’s re-enlistment certificate offers no reason for his decision, but the context for signing on for an additional tour of duty can be explained through the experience of other Union soldiers, Since the South fought on, there was a sense of unfinished business, along with a goal of renewing the substance of shared sacrifice and camaraderie of military life. Additionally, volunteers in 1864 received bonuses that could total $300, or about $4,400 in today’s money, along with the steady monthly pay of $13. These levels of remuneration likely attracted an unmarried man with no family commitments in Mt. Vernon. The decision to join the 15th confirmed Schlote’s preference for the familiarity and language compatibility of serving with soldiers of German descent.

Trained to handle the largest canon, heavy artillery regiments were stationed as defensive troops near the nation’s capital. That posting shifted in the spring of 1864, when Ulysses S. Grant assumed command of the Union army in Virginia, beginning a more sustained pursuit of the Confederates under General Robert E. Lee. General Grant insisted on gathering all available Northern troops for a massive offensive against the South, and he transferred many of the heavy artillery regiments -- including the 15th N.Y.H.A., assigned to the Fifth Corps -- to the Army of the Potomac for a campaign beginning in May.

The immigrant from Hanover grappled through the fighting until March 31, 1865, when he was wounded at the Battle of Five Forks, a Union victory which severed the last Confederate supply line to the west from Petersburg. A surgeon reported that Private Schlote’s gunshot wound in the right hip left him “totally unfit for military duty being unable to carry his belts and equipments,” recommending a discharge on account of disability. With the war’s conclusion in sight, Schlote remained in service until mustering out with his company at Washington, D.C. on August 22.

Sharing with other Northern veterans the deep satisfaction of having helped save the Union, he returned to Mt. Vernon, living another two decades. Shortly after the war he married Catherin, a woman 21 years his junior, who was also a German immigrant. Their first child, Hannah, was born in 1867; the couple had a son Herman in 1876. Local population growth and expansion of the housing stock created the circumstances for Schlote to obtain employment as a painter, although enduring effects from the injury suffered at Five Forks caused him in 1879 to apply for a disability pension based on his military service.

He died October 1, 1886 at age 60, followed by burial in the section of the cemetery reserved for community residents who were not St. Paul’s congregants. Schlote’s small gravestone reflects his service in the 15th N.Y.H.A, signaling the Government’s social responsibility to provide memorials for veterans. The marble marker is one of the earliest monuments for a Civil War solider at St. Paul’s, erected only seven years after Congress authorized the availability of the veterans’ stone to all Union troops. Originally, the vertical stones marked the graves of men killed in action and buried in national cemeteries. The emerging political influence of Union veterans, along with the cumulative deaths of former soldiers by natural causes, led to this change in distribution of the Government stone.