Last updated: March 14, 2022

Article

Vegetation Mapping at Saguaro National Park

Why Do Vegetation Mapping?

Vegetation maps visually display the distribution of vegetation communities across a landscape. Knowing what’s growing where, and what kinds of habitat occur in a park, helps park managers with park planning, resource monitoring, interpretive programs, prescribed fire, wildland firefighting, and climate-change response, among other activities. Vegetation maps also provide a baseline for other ecological studies. But in the past, not all parks had current vegetation maps.

The National Park Service (NPS) Vegetation Inventory Program aims to complete baseline mapping and classification inventories at more than 270 NPS units. Each map represents hundreds to thousands of hours of effort by ecologists, field technicians, GIS technicians, data managers, editors, and park staff. The teams use data collected from vegetation plots to classify vegetation types and write descriptions, and use aerial imagery to spatially delineate (map) where each vegetation type is found. Then they assess the accuracy of the results, create a geodatabase and map, and write a final report. Each finished project is an entire library of vegetation data and descriptive information.

Vegetation Mapping at Saguaro National Park

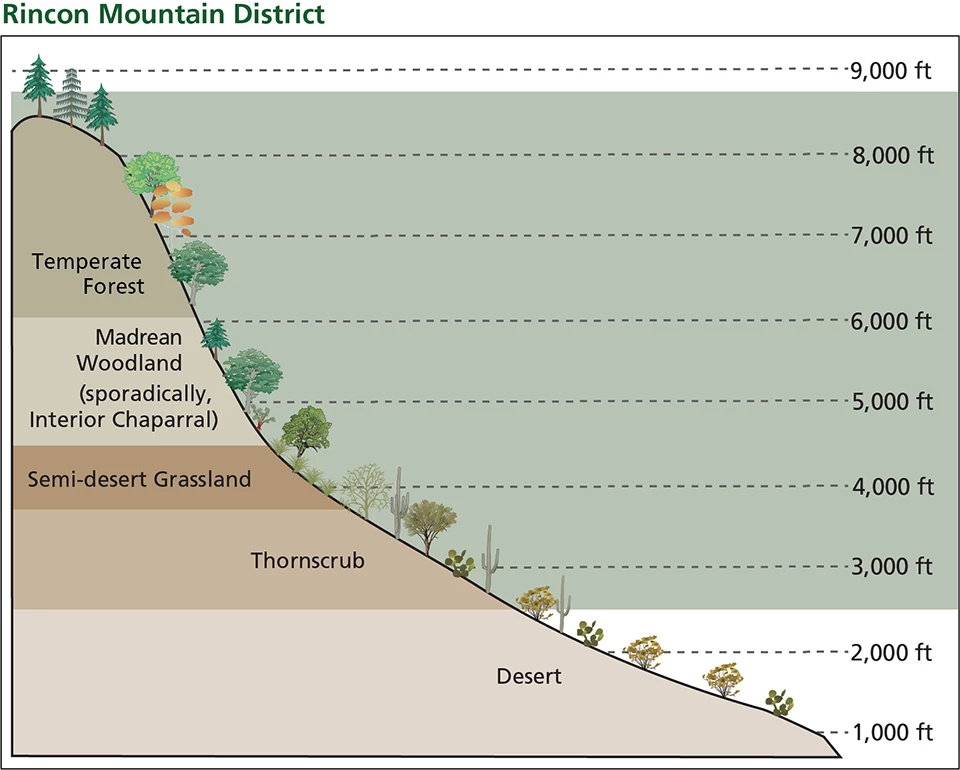

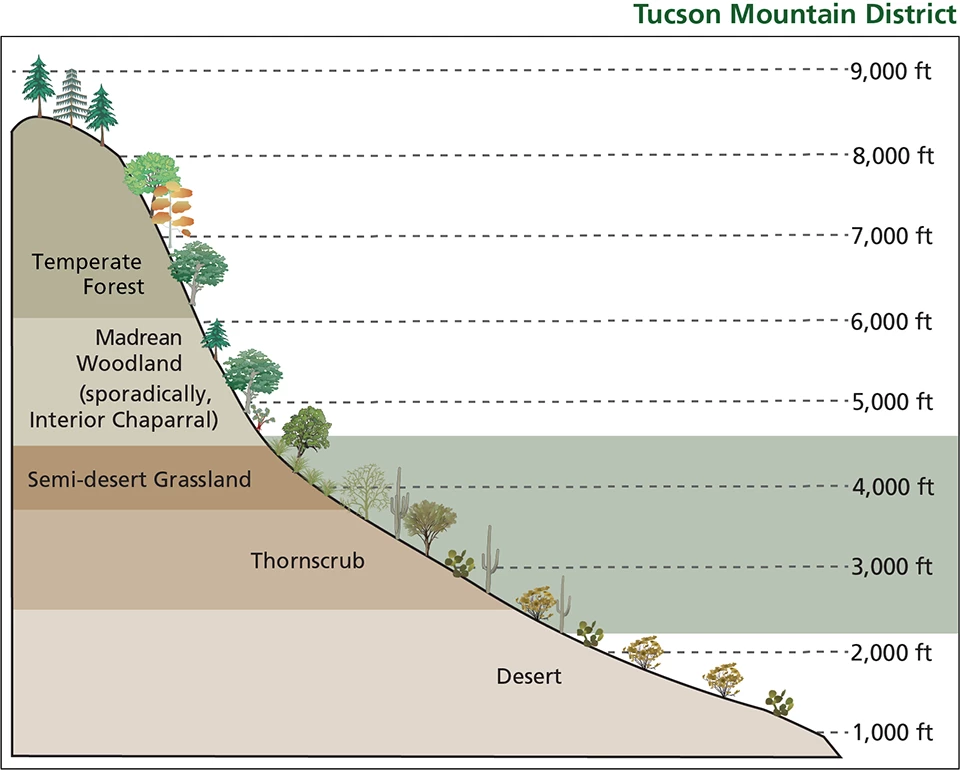

The Sonoran Desert Network conducted vegetation mapping at Saguaro National Park from 2010 to 2018. Located at opposite ends of Tucson, Arizona, the park’s two units span the Rincon and Tanque Verde Mountains to the east of Tucson (the Rincon Mountain District, or RMD), and the Tucson Mountains to the west of Tucson (the Tucson Mountain District, or TMD). These units were completed as separate projects due to their large size and considerable differences in vegetation communities, elevational range, and geology.

Elevation Range of Rincon and Tucson Mountain Districts

Left image

Life zones of the Rincon Mountain District

Right image

Life zones of the Tucson Mountain District

A vegetation community is a group of plants that lives together in a similar environment. Which plant species grow together can depend on many factors, including elevation, climate, soil type, growth stage, and history of disturbances (e.g., wildfire). Vegetation communities can be identified at multiple scales, from vegetation “divisions”—patterns that repeat across wide continental or climatic regions—to plant “associations” whose interactions can be very specific to a particular geographic context. The National Vegetation Classification (NVC) provides a complete list of vegetation types described in the United States.

At Saguaro National Park, a total of 97 distinct vegetation associations were described: 83 exclusively at the RMD, 9 exclusively at the TMD, and 5 occurring in both districts. These communities ranged from low-elevation creosote (Larrea tridentata) shrublands spanning broad alluvial fans to mountaintop Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) forests on the slopes of Rincon Peak. All 97 communities were described at the association level, through detailed narratives including lists of species found in each association, their abundance, landscape features, and overall community structural characteristics. Only 15 of the 97 vegetation types were existing “accepted” types within the NVC. The others are newly described and specific to Saguaro National Park. They will be proposed for formal status within the NVC.

Vegetation Associations Identified at Saguaro National Park

Each pdf summary in the table below briefly describes the floristic and structural characteristics of the vegetation and includes a representative photo of the association (left-side page), the association’s distribution across the park (top of right-side page), and an example of the satellite imagery for one polygon (bottom of right-side page). When distribution is limited to a certain part of a district, the area shown in the distribution map is indicated by the red box in an accompanying district map. In the text, numbers to the first decimal in parentheses indicate frequency. A plant with a value of (1.0) means that species was documented in every plot (100%) of that association. Readers may refer to the digital maps and databases accompanying this report for more detail.

See table of associations

(P)=proposed association, RMD=Rincon Mountain District, TMD=Tucson Mountain District

Park Flora

Over the course of this project, a total of 538 species were observed on plots: 506 at the RMD and 154 at the TMD, with 122 species recorded at both districts. Three new species were identified and added to the park plant checklist:

- scarlet monkeyflower (Mimulus cardinalis)

- American black nightshade (Solanum americanum)

- nightblooming cereus (Peniocereus greggii var. transmontanus)

In addition, one species believed to be extirpated from the park, smooth sumac (Rhus glabra), was documented.

Wildfires Impact Conifer Communities

From the late 1980s to the early 2000s, four major fires impacted vegetation communities in the Rincon Mountains—to the detriment of some species and benefit of others. Whether these communities will return to their pre-fire state depends on many variables, including fire severity, the fire resistance of dominant species, and the dominant species’ post-fire response.

For instance, in 2003, the Helen’s 2 Fire burned the northern slopes of Mica Mountain, mainly in ponderosa pine and Douglas fir forests. With their thick bark, deep roots, and high crowns, mature trees of these species are highly resistant to low- and moderate-severity fire. Despite this resistance, vast areas covered by this fire exhibited near-complete tree mortality. These species rely on seed germination to re-establish burned areas. But in the years surrounding the fire, most of Arizona experienced a severe drought that limited cone production. Post-fire establishment of vast, dense areas of western brackenfern may also have hindered germination. Ten years after the fire, there was no recruitment of ponderosa pine or Douglas fir in 30% of plots sampled within the boundaries of the fire.

The Chiva (1989) and Box Canyon (1999) fires burned through similar vegetation communities that have experienced similar post-fire impacts. Within the bounds of these fires, areas previously defined by the presence of conifers were mapped as oak and/or manzanita communities in this project. Unlike conifers, oaks can often re-sprout from the root crown following a fire event. This can lead to rapid expansion of shrubby oak throughout burned areas. Manzanita can also quickly re-establish in burned areas, often causing a type conversion from pinyon-juniper woodland to manzanita shrublands.

The increased warming and drying of the climate in the 21st century is leading to a decrease in post-fire tree regeneration compared to the end of the 20th century. This is especially true where dominant species (like conifers) are at the lower elevational end of their typical range.

The Sonoran Desert Network will continue to monitor vegetation and soils at Saguaro National Park as part of its long-term vital signs monitoring program.

Learn More

For more information on vegetation mapping at Saguaro National Park, read the project reports or contact Sonoran Desert Network vegetation ecologist Sarah Studd.