Last updated: October 24, 2024

Article

Climate and Water Monitoring at Saguaro National Park, Water Year 2021

Storm over Saguaro National Park (NPS).

Overview

Together, climate and hydrology shape ecosystems and the services they provide, particularly in arid and semi-arid ecosystems. Understanding changes in climate, groundwater, and surface water is key to assessing the condition of park natural resources—and often, cultural resources.

At Saguaro National Park (NP), Sonoran Desert Network (SODN) scientists study how ecosystems may be changing by taking measurements of key resources, or “vital signs,” year after year, much as a doctor keeps track of a patient’s vital signs. This long-term ecological monitoring provides early warning of potential problems, allowing managers to mitigate them before they become worse. At Saguaro, we monitor climate, weather, groundwater, and springs, among other vital signs.

Surface-water and groundwater conditions are closely related to climate conditions. Because they are better understood together, we report on climate in conjunction with water resources. Reporting is by water year (WY), which begins in October of one calendar year and goes through September of the next.

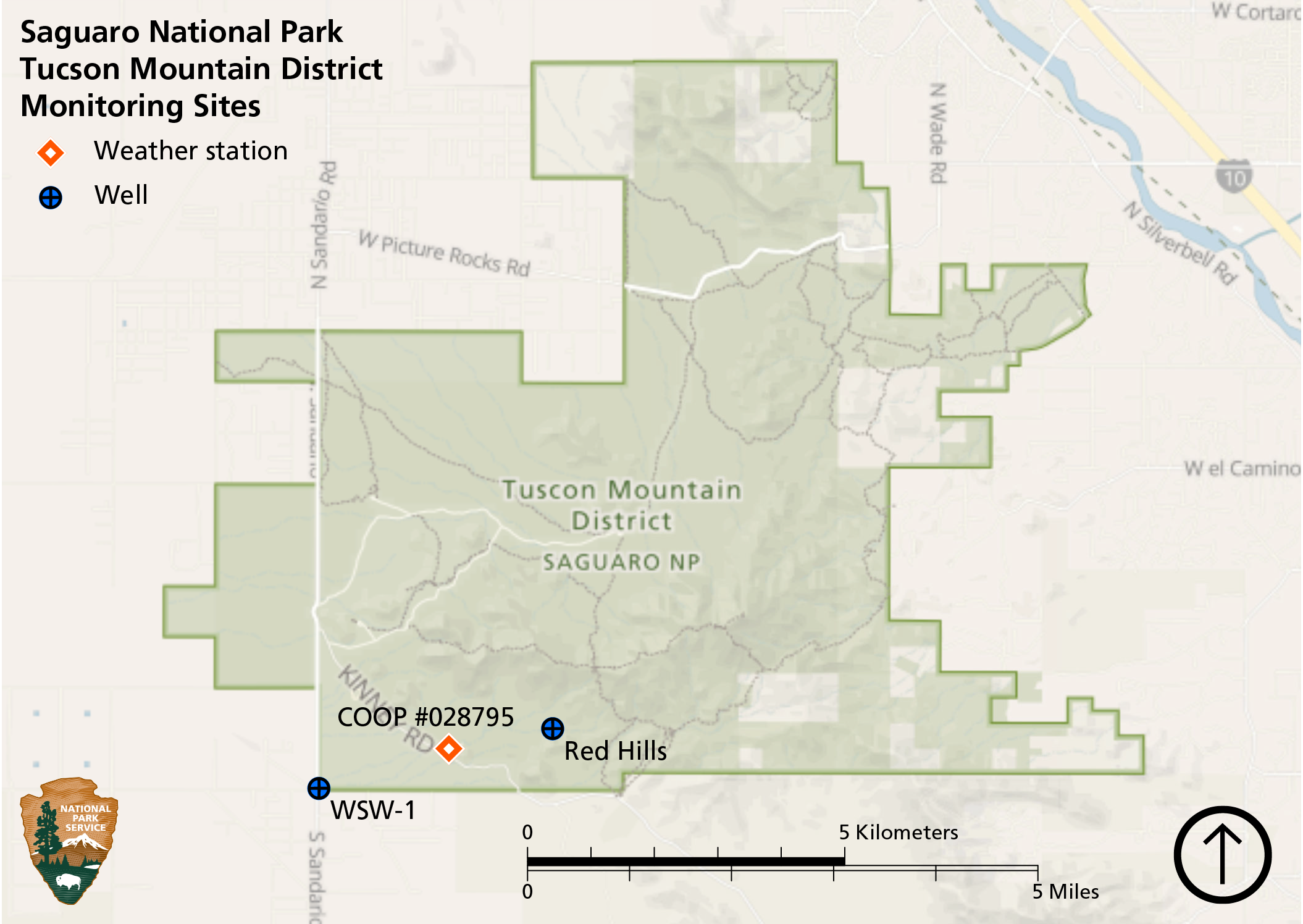

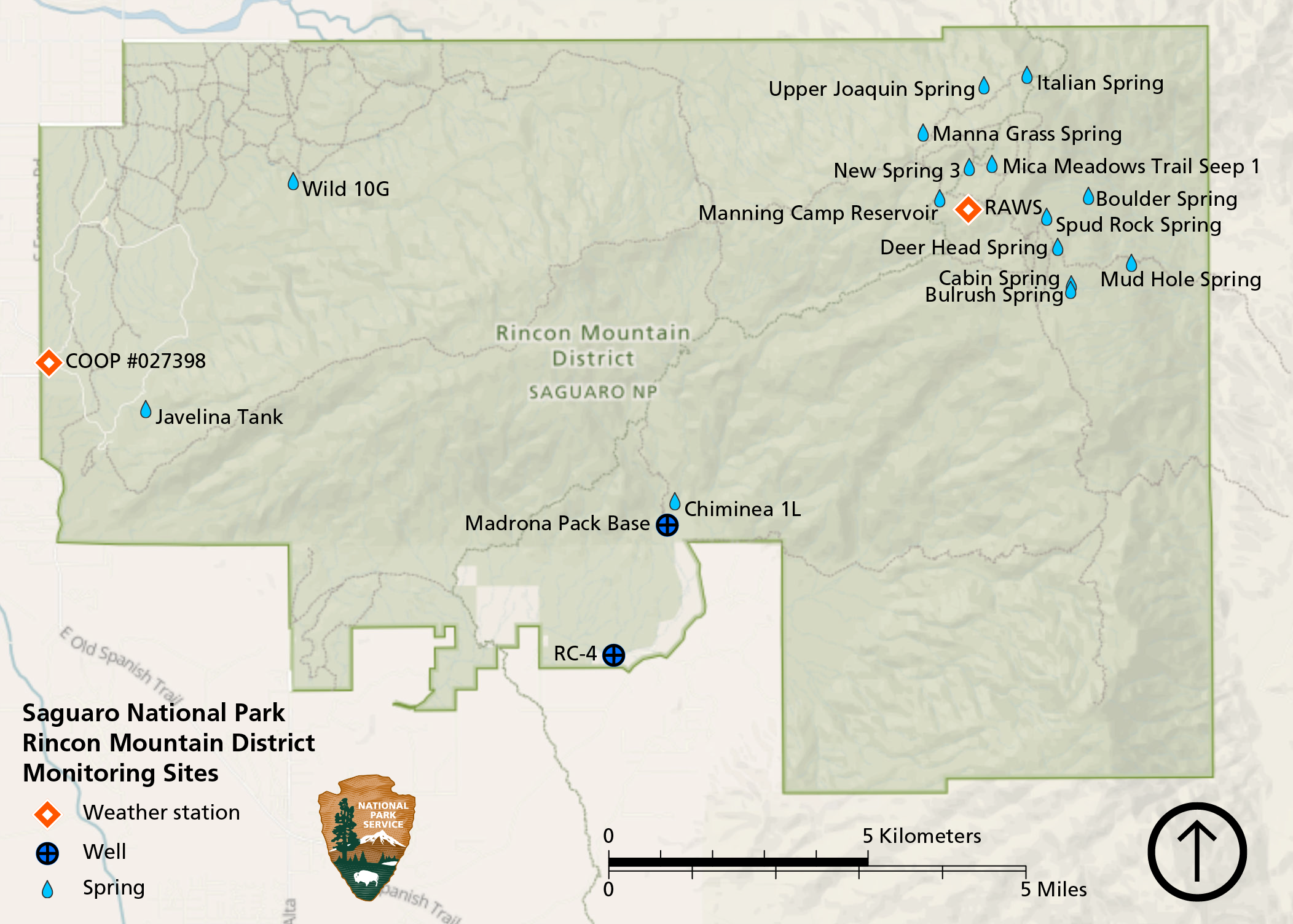

Information in this report covers climate, groundwater, and springs monitoring at Saguaro National Park's Tucson Mountain District (TMD, Figure 1) and Rincon Mountain District (RMD, Figure 2) for water year 2021 (October 1, 2020–September 30, 2021).

Figure 1. Monitored weather stations and groundwater wells at Saguaro National Park’s Tucson Mountain District in WY2021.

Figure 2. Monitored weather stations, groundwater wells, and springs at Saguaro National Park’s Rincon Mountain District in WY2021.

Climate and Weather

There is often confusion over the terms, “weather” and “climate.” In short, weather describes instantaneous meteorological conditions (e.g., it's currently raining or snowing, it’s a hot or frigid day). Climate reflects patterns of weather at a given place over longer periods of time (seasons to years). Climate is the primary driver of ecological processes on earth. Climate and weather information provide context for understanding the status or condition of other park resources.

Saguaro NP operates two National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Cooperative Observer Program (COOP) weather stations: Tucson 17 NW #028795, near the Tucson Mountain District (TMD) visitor center (see Overview, Figure 1), has been in operation since 1982. Saguaro National Park #027398, near the Rincon Mountain District (RMD) visitor center (see Overview, Figure 2), has been in operation since 2008. These stations typically provide a reliable climate dataset. However, in WY2021, the TMD COOP station was missing data on 346 days and the RMD COOP station was missing data on 48 days. As a substitute, climate analyses in this year’s report use 30-year averages (1991–2020) and gridded surface meteorological (GRIDMET) data from the location of the COOP stations and. Subsequent reports may revert to the weather stations as the data source, depending on future data quality. Additionally, a Remote Automated Weather Station (RAWS), Rincon Arizona #021207, has been in operation since 1994, located in the RMD at an elevation of 8,209 ft (2,502 m).

GRIDMET is a spatial climate dataset at a 4-kilometer resolution that is interpolated using weather-station data, topography, and other observational and modeled land-surface data. Temperature and precipitation estimated from GRIDMET may vary from actual weather at a particular location, depending on the availability of weather-station data and the difference in elevation between the location and that assigned to a grid cell. Data from both the weather station and GRIDMET are accessible through Climate Analyzer.

Results for Water Year 2021

Precipitation

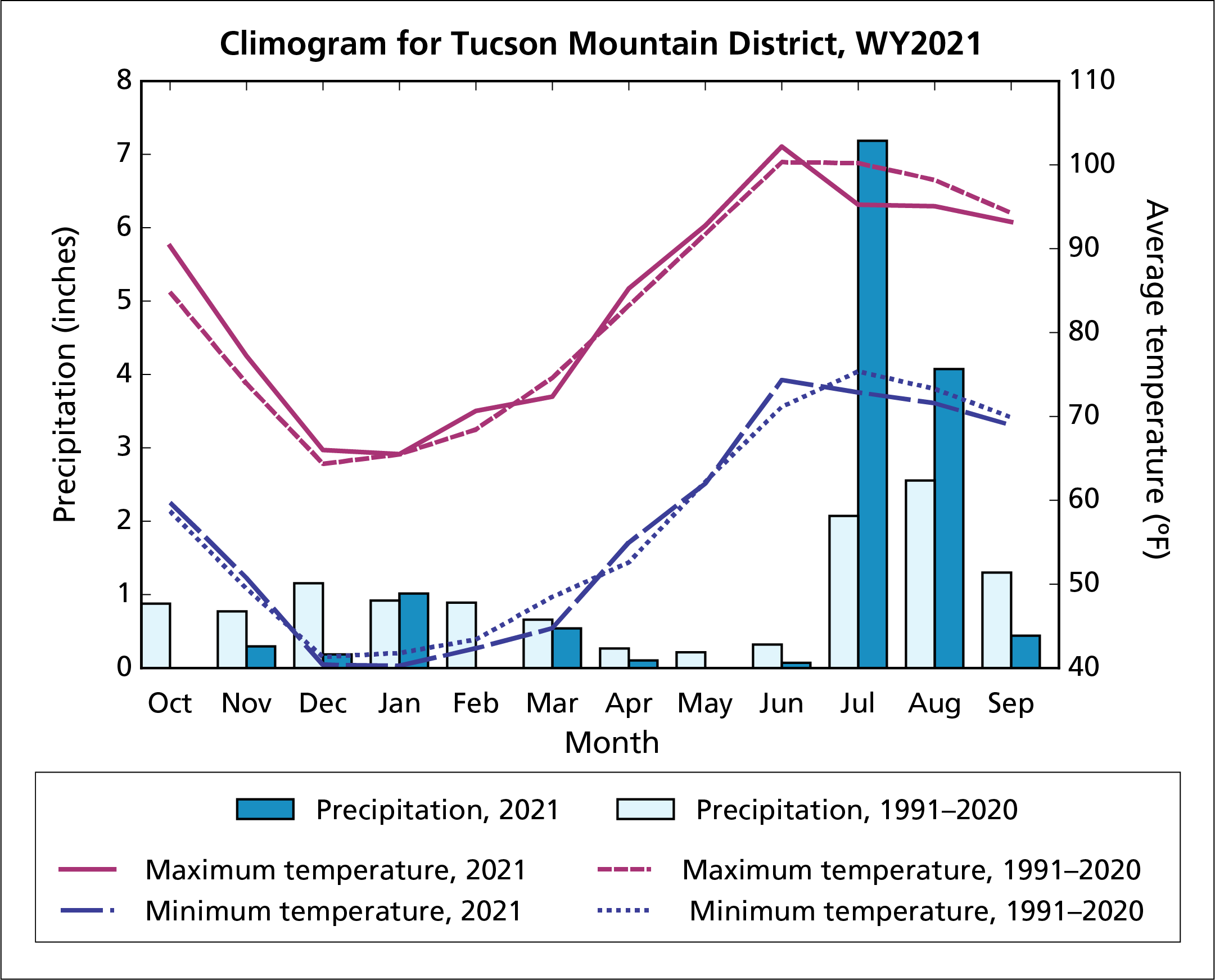

TMD Visitor Center (GRIDMET). Annual precipitation at Saguaro NP at the TMD visitor center in WY2021 was 13.91" (35.3 cm; Figure 1), which was 1.91" (4.9 cm) more than the 1991–2020 annual average. This surplus occurred primarily in July and August, when the park received 11.26" (28.6 cm)—over four times the 30-year mean for those two months. Conversely, precipitation during the rest of the year was generally below the 30-year monthly averages.

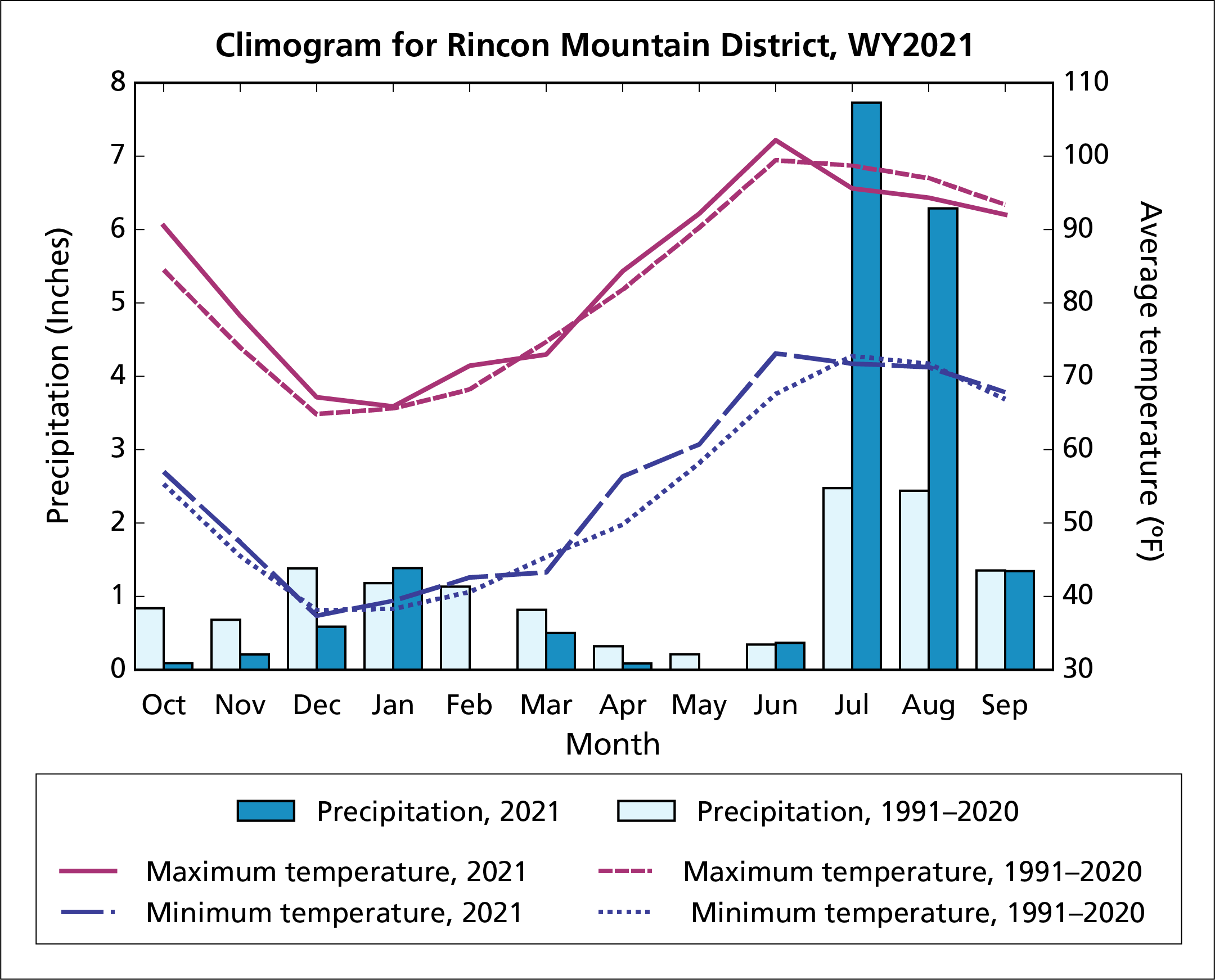

RMD Visitor Center (GRIDMET). Annual precipitation at Saguaro NP at the RMD Visitor Center in WY2021 was 18.58" (47.2 cm; Figure 2), which was 5.41" (13.7 cm) more than the 1991–2020 annual average. This surplus occurred primarily in July and August, when the park received 14.02" (35.6 cm), nearly three times the 30-year mean for those two months. Precipitation prior to the onset of the monsoon season (October–May) was generally drier than the 30-year monthly averages.

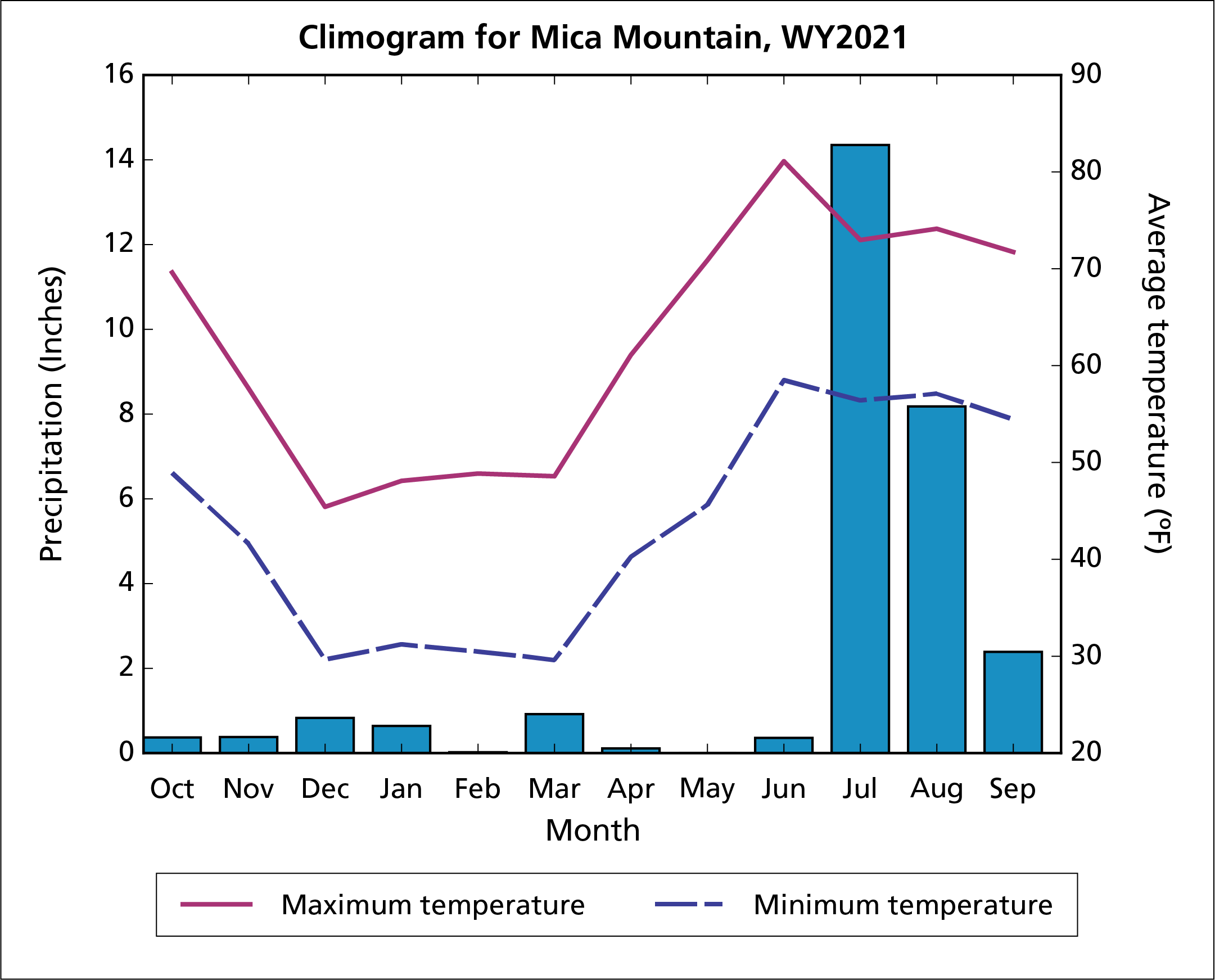

RMD high elevations (RAWS). Annual precipitation at the RMD RAWS station in WY2021 was 28.55" (72.5 cm; Figure 3), which was 6.33" (16.1 cm) more than the annual mean for 1995–2020. This surplus occurred primarily in July and August, when the Rincon Mountains received 22.53" (57.2 cm)—79% of the total WY2021 rainfall, and over twice the average total for July and August (10.04"/25.5 cm) from 1995 to 2020. The months from October through June all had rainfall totals of <1" (2.54 cm). Extreme daily rainfall events (≥1"; 2.54 cm) occurred on nine days, which was twice the annual frequency (4.5 days) for 1995–2020. The largest daily rainfall event was 3.21" on August 14, 2021.

Figure 1. Climogram showing monthly precipitation and mean maximum and minimum temperature for WY2021 and the 1991–2020 means at the RMD visitor center. Data source: GRIDMET via climateanalyzer.org.

Figure 2. Climogram showing monthly precipitation and mean maximum and minimum temperature for WY2021 and the 1991–2020 means at the TMD visitor center. Data source: GRIDMET via climateanalyzer.org.

Figure 3. Climogram showing monthly precipitation and mean maximum and minimum temperature for WY2021 at the high-elevation RMD RAWS station. Data source: GRIDMET via climateanalyzer.org.

Air temperature

TMD Visitor Center (GRIDMET).The average annual maximum air temperature at the TMD Visitor Center in WY2021 was 83.9°F (28.8°C), which was 0.5°F (0.3°C) warmer than the average annual maximum for 1991–2020. The average annual minimum air temperature was 57.0°F (13.9°C), which was slightly cooler (0.4°F/0.2°C) than the 1991–2020 average minimum. Mean monthly maximum and minimum temperatures in WY2021 varied up to 5.5°F (2.9°C) relative to the 1991–2020 average monthly temperatures (see Figure 1).

RMD Visitor Center (GRIDMET).The average annual maximum air temperature in WY2021 at the RMD Visitor Center was 83.9°F (28.8°C), 1.2°F (0.7°C) warmer than the 1991–2020 average annual maximum. The average annual minimum air temperature in WY2021 was 55.7°F (13.1°C), which was 1.5°F (0.8°C) warmer than the 1991–2020 average minimum. Average monthly maximum and minimum temperatures in WY2021 were generally warmer than 1991–2020 average monthly temperatures (up to 6.6°F, 3.7°C) until the frequent monsoon storms in July and August led to cooler than average temperatures (see Figure 2).

RMD high elevations (RAWS). The average annual maximum air temperature in WY2021 at the RMD RAWS station was 62.6°F (17.0°C), which was slightly cooler than the 1995–2020 average maximum by 0.3°F (0.2°C). The average annual minimum air temperature in WY2021 was 43.8.0°F (6.6°C), 1.2°F (0.7°C) warmer than the 1995–2020 average minimum. Extremely hot temperatures (>83°F; 28.3°C) occurred on 11 days, less than the 1995–2020 annual frequency (18.6). Extremely cold temperatures (<23°F; -5.0°C) occurred on 21 days, almost the same as the 1995–2020 annual frequency (21.9 days) (see Figure 3).

Drought

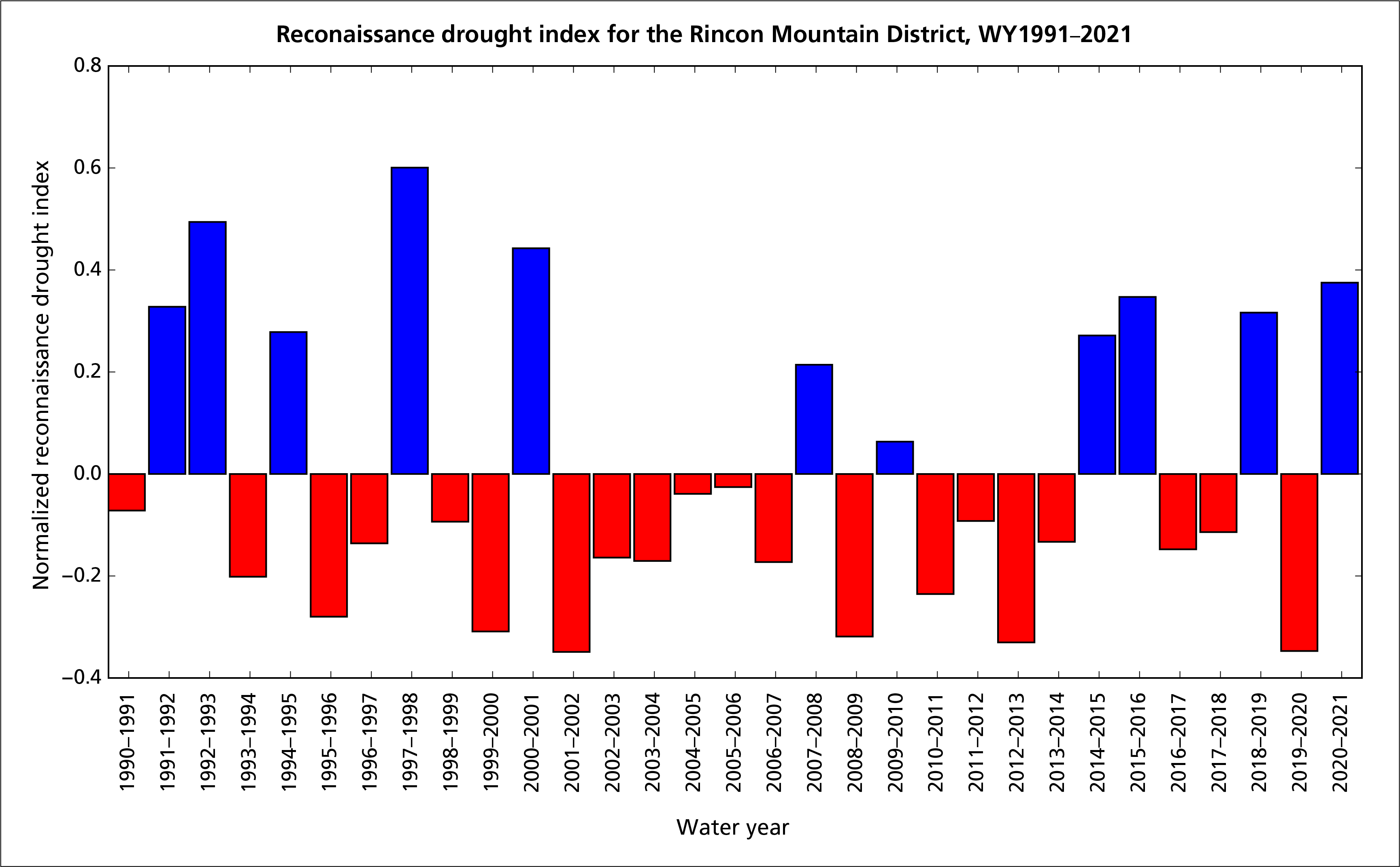

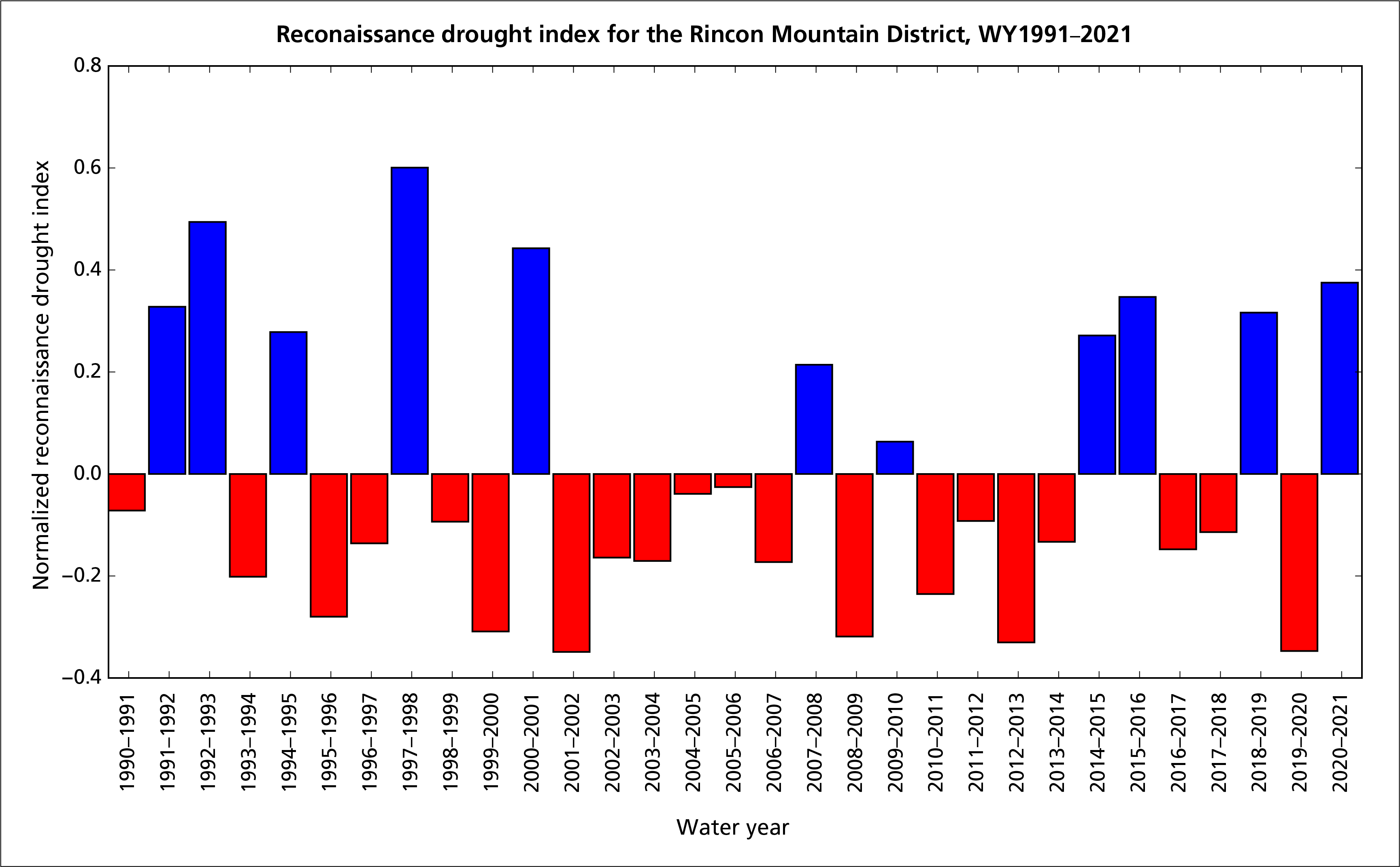

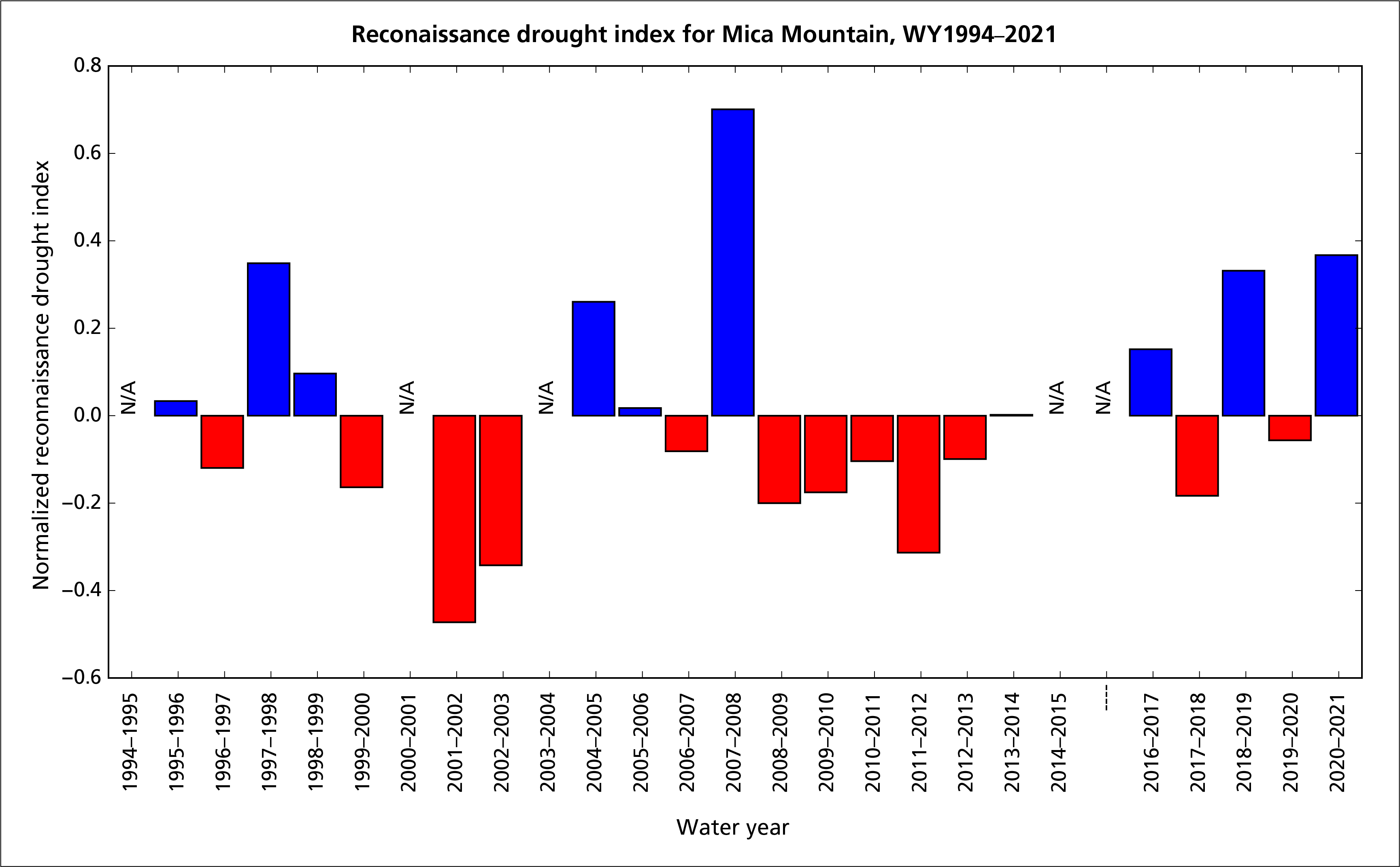

Reconnaissance drought index (Tsakiris and Vangelis 2005) provides a measure of drought severity and extent relative to the long-term climate. It is based on the ratio of average precipitation to average potential evapotranspiration (the amount of water loss that would occur due to evaporation and plant transpiration if the water supply was unlimited) over short periods of time (seasons to years). The reconnaissance drought indices for Saguaro NP indicate that WY2021 was wetter than the averages for 1991–2020 (GRIDMET) or 1995–2020 (RAWS) from the perspectives of both precipitation and potential evapotranspiration. In addition, the RMD was relatively wetter at both lower and higher elevations than the TMD (Figures 4–6).

Figure 4. Reconnaissance drought index for the TMD visitor center, Saguaro National Park, WY1991–2021. Drought index calculations are relative to the time period selected (1990–2021). Choosing a different set of start/end points may produce different results. Data source: GRIDMET via climateanalyzer.org.

Figure 5. Reconnaissance drought index for the RMD visitor center, Saguaro National Park, WY1991–2021. Data source: GRIDMET via climateanalyzer.org.

Figure 6. Reconnaissance drought index at the high-elevation RMD RAWS station, Saguaro National Park, WY1995–2021. “N/A” = insufficient data to generate reliable estimates. Data source: GRIDMET via climateanalyzer.org.

Groundwater

Groundwater is one of the most critical natural resources of the American Southwest. It provides drinking water, irrigates crops, and sustains rivers, streams, and springs throughout the region. Groundwater is closely linked to long-term precipitation and surface waters, as ephemeral flows sink below ground to reappear months, years, or even centuries later as perennial and intermittent streams and springs. Groundwater also sustains vegetation and is the primary source of water for almost all humans in the southwestern U.S. Groundwater therefore interacts either directly or indirectly with all key ecosystem features of the arid Sonoran Desert ecoregion.

At Saguaro NP, groundwater is monitored using four wells (see Figures 1 and 2 in the Overview). In the TMD, SODN has manually monitored WSW-1 quarterly since 2009, and Red Hills Well continuously since 2015. In the RMD, park staff and volunteers have monitored Madrona Pack Base continuously since 2011. RC-4 has been monitored manually on a monthly basis since 2005, and continuously since WY2017. Due to equipment failure in WY2021, water-level data for the RMD wells are incomplete. Only a single manual measurement is available for the Madrona Pack Base well. RC-4 had continuous data only for October 1–November 4, 2020.

Results for Water Year 2021

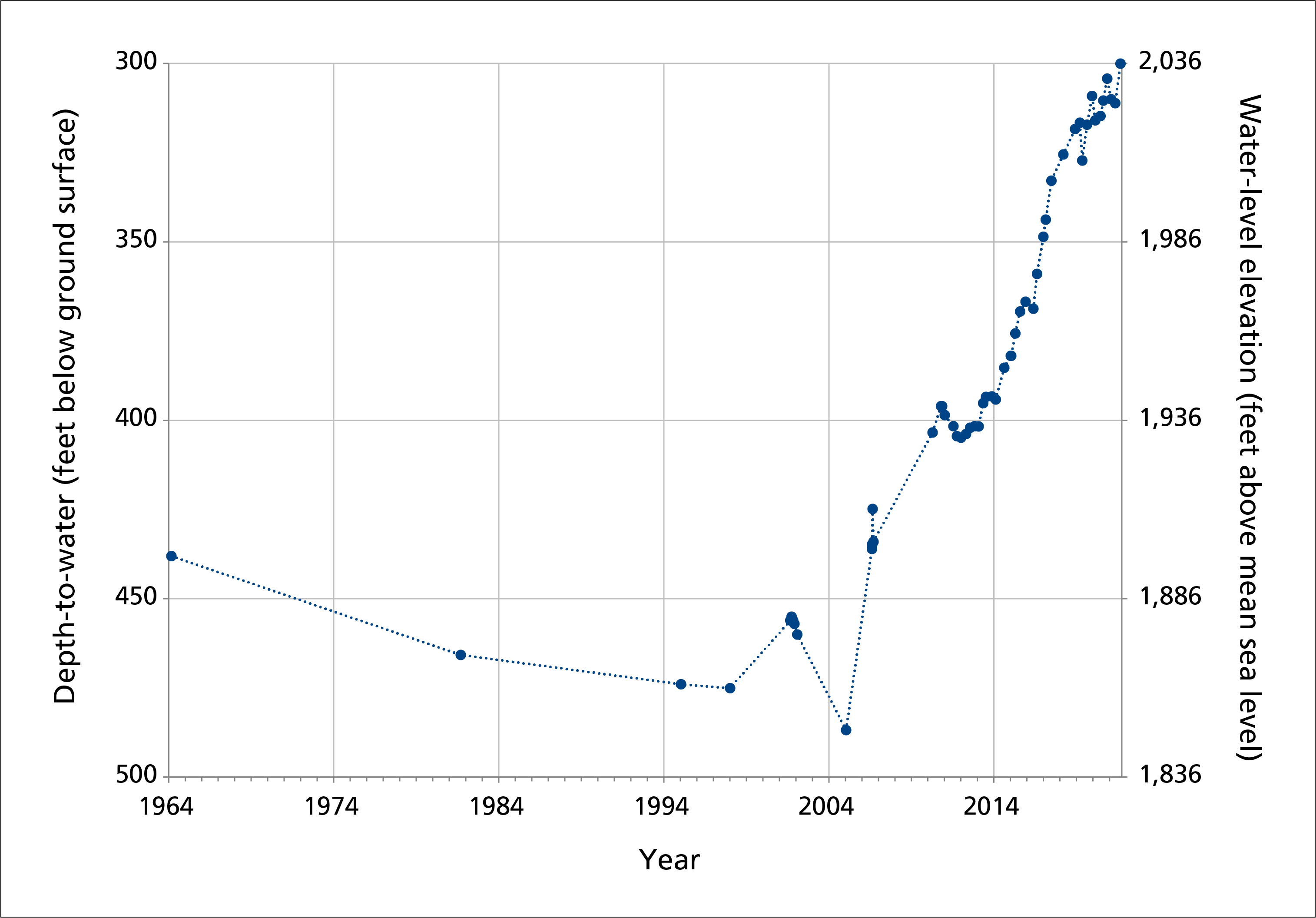

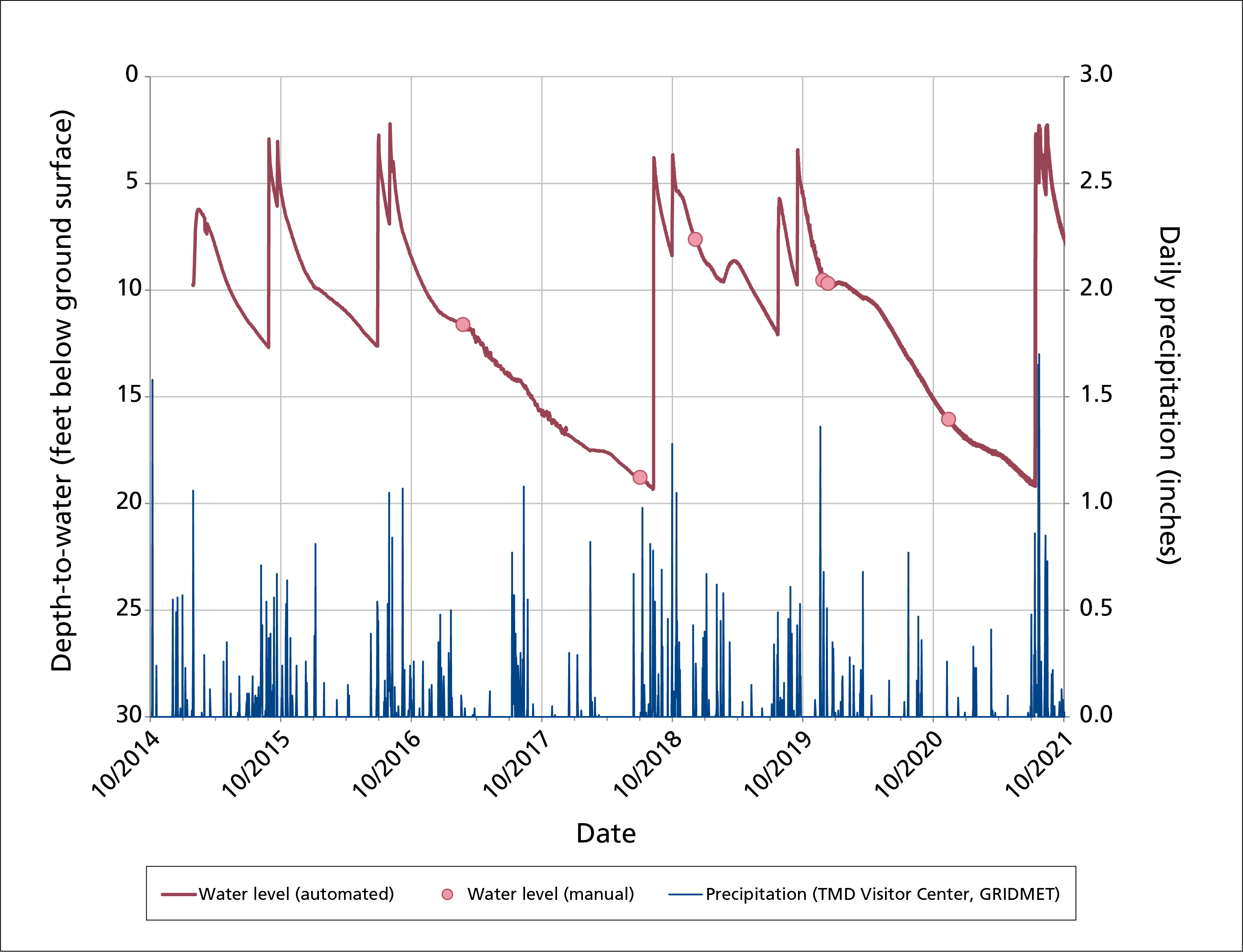

Groundwater monitoring results for WY2021 are summarized in Table 1. Mean depth-to-water at WSW-1 was 306.35 feet (93.38 m) below ground surface (bgs), which was somewhat higher than in WY2020 and 180.51 feet (55.02 m) higher than the lowest water level, observed in 2005 (Figure 1). The aquifer has been recovering in response to recharge of Central Arizona Project water via the Central Avra Valley Storage and Recovery Project. Water levels at Red Hills Well declined steadily through the beginning of WY2021, reaching the lowest level (19.19 ft/5.85 m bgs) in July (Figure 2). Monsoon rain events recharged the shallow aquifer, which peaked at 2.27 feet (0.69 m) bgs in August.

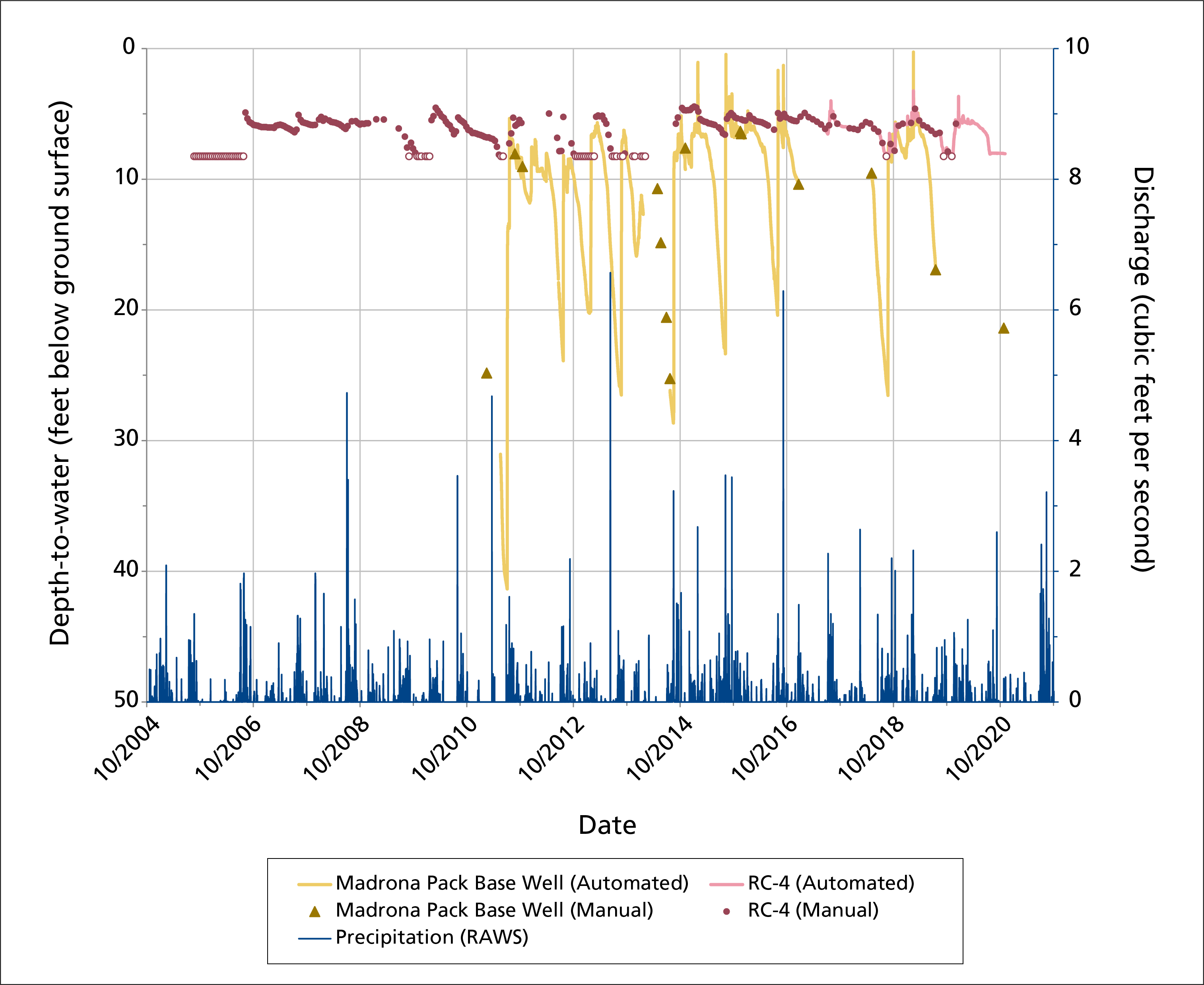

A single water-level measurement at Madrona Pack Base well was 21.39 feet (6.52 m) bgs, which was within the historic range for the well (Figure 3). Continuous measurements at RC-4 indicated that the well was dry for the period of available data in WY2021. RC-4 has been recorded as dry during part of 11 of the past 17 water years. Both the Madrona Pack Base and RC-4 wells showed increasing water-level elevations following sufficient precipitation and surface flow in the Rincon Creek watershed.

Table 1. Groundwater monitoring results in water year 2021, Saguaro National Park.*

| Name | State well number | Park unit | Wellhead elevation (feet amsl) | Mean depth-to-water (feet bgs) | Mean water-level elevation (amsl feet) | Change in elevation from water year 2020 (± feet) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WSW-1 | 629094 | TMD | 2,336 | 306.35 | 2,029.65 | +6.19 |

| Red Hills | 629095 | TMD | 2,795.00 | 14.65 | 2,780.35 | −3.70 |

| Madrona Pack Base | 629099 | RMD | 3,350.00 | 21.38 | 3,328.62 | Not applicable |

| RC-4 | 206880 | RMD | 3,150.42 | well dry | well dry | Not applicable |

* amsl = above mean sea level; bgs = below ground surface; TMD = Tucson Mountain District; RMD = Rincon Mountain District.

Figure 1. Depth-to-water (feet below ground surface) at WSW-1, 1964–2021, Saguaro National Park. The sharp increase since 2005 reflects recharge from the Central Avra Valley Storage and Recovery Project.

Figure 2. Depth-to-water (feet below ground surface) at Red Hills well, and daily precipitation based on GRIDMET data at the TMD visitor center, water years 2015–2021, Saguaro National Park.

Figure 3. Depth-to-water (feet below ground surface) at Madrona Pack Base and RC-4 wells, and daily precipitation from the TMD RAWS station, water years 2005–2021, Saguaro National Park. White circles indicate manual measurements collected when the well was dry.

Springs

Background

Springs, seeps, and tinajas are small, relatively rare biodiversity hotspots in arid lands. They are the primary connection between groundwater and surface water, and are important water sources for park plants and animals. For springs, the most important questions we ask are about persistence (How long was there water in the spring?), and water quantity (How much water was in the spring?).

Climate change is an emerging impact on springs in the American Southwest. Anticipated changes include increased air temperatures, evaporation rates, and drought intensity; more frequent and extreme rainfall and heat events; and potentially reduced precipitation in the winter and spring. These changes may cause springs to experience reduced flow or even go dry, which may disrupt ecological functions, reduce species diversity, and negatively impact visitor experience.

Sonoran Desert Network springs monitoring is organized into four modules, described below.

Site characterization

This module, which includes recording GPS locations and drawing a site diagram, provides context for interpreting change in the other modules. We also describe the spring type (e.g., helocrene, limnocrene, rheocrene, or tinaja) and its associated vegetation. Helocrene springs emerge as low-gradient wetlands. Limnocrene springs emerge as pools, and rheocrene springs emerge as flowing streams. This module is completed once every five years or after significant events.

Site condition

We estimate natural and anthropogenic disturbances and the level of stress on vegetation and soils on a scale of 1–4, where 1 = undisturbed, 2 = slightly disturbed, 3 = moderately disturbed, and 4 = highly disturbed. Types of natural disturbances can include flooding, drying, fire, wildlife impacts, windthrow of trees and shrubs, beaver activity, and insect infestations. Anthropogenic disturbances can include roads and off-highway vehicle trails, hiking trails, livestock and feral-animal impacts, removal of invasive non-native plants, flow modification, and evidence of human use. We take repeat photographs showing the spring and its landscape context. We note the presence of certain obligate wetland plants (plants that almost always occur only in wetlands), facultative wetland plants (plants that usually occur in wetlands, but also occur in other habitats), and non-native bullfrogs and crayfish, and we record the density of invasive, non-native plants.

Water quantity

We measure the persistence of surface water, amount of spring discharge, and wetted extent. To estimate persistence, we analyze the variance of temperature measurements taken by logging thermometers placed at or near the orifice (spring opening). Because water mediates variation in diurnal temperatures, data from a submerged sensor will show less daily variation than data from an exposed open-air sensor; this tells us when the spring was wet or dry. Surface discharge is measured with a timed sample of water volume. Wetted extent is a systematic measurement of the physical length (up to 100 m), width, and depth of surface water. It is assessed using a technique for either standing water (e.g., limnocrene and helocrene springs) or flowing water (e.g., rheocrene springs).

Water quality

We measure core water-quality parameters and water chemistry. Core parameters include water temperature, pH, specific conductivity (a measure of dissolved compounds and contaminants), dissolved oxygen (how much oxygen is present in the water), and total dissolved solids (an indicator of potentially undesirable compounds). Discrete samples of these parameters are collected with a multiparameter meter. If the meter failed calibration check(s), we do not present data. Water chemistry is assessed by collecting surface water sample(s) and estimating the concentration of major ions with a photometer in the field. These parameters are collected at one or more sampling locations within a spring. Data are presented only for the primary sampling location. Each perennial spring is somewhat unique, and there are not water-quality standards specific to most perennial springs in Arizona. Where conditions exceed water-quality standards for other surface waters (rivers, streams, lakes, and reservoirs), we note it, but the reader is advised that these standards were not developed for perennial springs. Our ongoing data collection at each spring will improve our understanding of the natural range in water-quality and water-chemistry parameters for a given site.

Results for Water Year 2021 at Low-Elevation Springs

Chimenea 1L | Javelina Tank | Wild 10G

Chimenea 1L

Chimenea 1L (Figure 1, left) was characterized in WY2017. It is part of a multi-pool tinaja complex (pools within rock basins) containing more than 15 flowing pools (Figure 1, right). The tinaja chosen for sampling, designated orifice A, is historically known to be persistently wetted but ephemerally connected by flow to other pools. This tinaja is approximately 3 × 4 meters (9.8 × 13.1 ft).

Figure 1. Left: Orifice A and sampling location 001 at Chimenea 1L, Saguaro National Park, April 2021. Right: Location of Chimenea 1L within a complex of at least 15 tinajas in lower Chimenea Canyon. NPS photos.

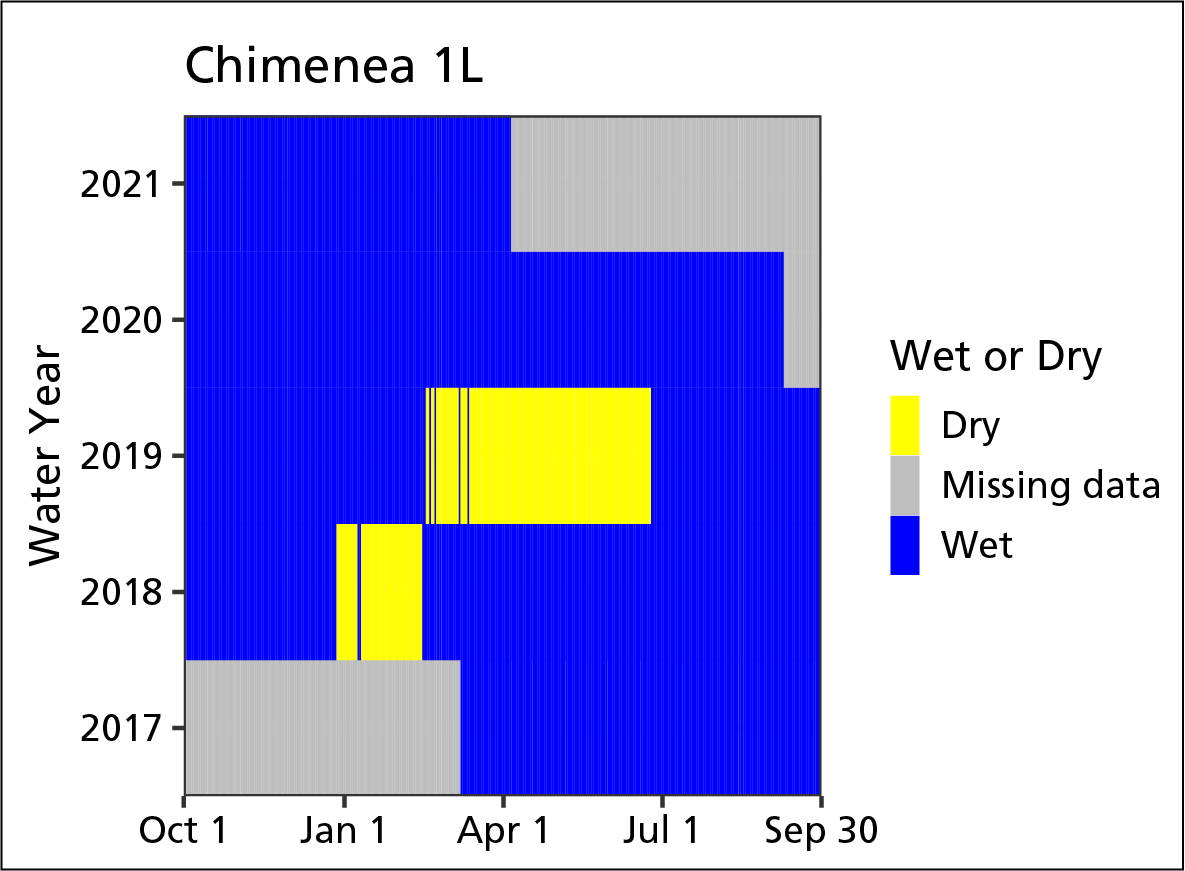

Figure 2. Water persistence in Chimenea 1L, Saguaro National Park, 2017–2021.

Figure 2. Water persistence in Chimenea 1L, Saguaro National Park, 2017–2021.Water quantity. The WY2021 visit occurred on April 6, 2021. The spring contained water. Temperature sensors indicated that Chimenea 1L was wetted for all 188 days (100%) measured up to the WY2021 visit (Figure 2). In prior water years, the spring was wetted 65.8–100% of the days measured.

Discharge was estimated at 2.1 (± 0.5) liters (0.6 ± 0.1 gal) per minute in WY2021 (Table 1). This was similar to the discharge measured in WY2018. There was no measurable discharge in WY2019.

Wetted extent was evaluated using a method for standing water. Width averaged 248.7 centimeters (97.9 in), length averaged 231 centimeters (90.9 in), and depth averaged 47.8 centimeters (18.8 in) (Table 2). These measurements were similar to those in WY2018–2019.

Water quality. Core water-quality and water-chemistry data were collected at the lower end of the pool (sampling location 001), as in previous years. Dissolved oxygen was slightly lower than in previous years, whereas pH, specific conductivity, and total dissolved solids were somewhat higher (Table 3).

Water-chemistry data were also collected at the primary sampling location. Chloride was approximately 7 times higher than in prior years, but well below concentrations that can be expected to negatively impact aquatic and terrestrial wildlife. Alkalinity and potassium where somewhat higher than in WY2017–2019 (Table 4).

Table 1. Discharge data (L/min; mean ± SD) for Chimenea 1L in water year 2021, and values from prior years.

| Sampling location | WY2021 value (Prior value) | Prior year measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| 001 | 2.1 ± 0.5 (1.6) | 2018 (1) |

Table 2. Average (± SD) width, length, and depth (cm) of Chimenea 1L in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Measurement | WY2021 value (Range of prior values) | Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| Width (cm) | 248.7 ± 84.7 (201.7–251.4) | 2018–2019 (2) |

| Depth (cm) | 47.8 ± 31.9 (45.5–57.2) | 2018–2019 (2) |

| Length (cm) | 231 ± 149.7 (242.3–243) | 2018–2019 (2) |

Table 3. Data on core water-quality parameters for Chimenea 1L in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location | WY2021 value (Range of prior values) |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | Center | 7.97 (9.04–9.51) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| pH | 001 | Center | 8.2 (7.36–7.77) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | Center | 84.3 (38.5–76.4) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | Center | 18.6 (14.2–19.4) | 2017–2019 (4) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | Center | 55 (31.2–49.9) | 2018–2019 (2) |

Table 4. Water-chemistry data (mg/L) for Chimenea 1L in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location | WY2021 value (Range of prior values) |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkalinity (CaCO3) | 001 | Center | 45 (15–35) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| Calcium (Ca) | 001 | Center | 4 (0–4) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| Chloride (Cl) | 001 | Center | 29 (3–4) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 001 | Center | 1 (bdl*–8) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| Potassium (K) | 001 | Center | 1.7 (0.4) | 2018–2019 (2) |

| Sulphate (SO4) | 001 | Center | 4 (1–4) | 2017–2019 (3) |

*bdl = below detection limits.

Javelina Tank

Javelina Tank (Figure 3) was last characterized in WY2017 and is a tinaja (small pool in rock basin or impoundment in bedrock). This tinaja is located in a west-facing drainage in the foothills of Tanque Verde Ridge. Orifice A is a plunge pool located at the base of a 10-meter cliff. Directly downstream, a bedrock seep feeds small (~1 × 1-m) and shallow (5–30 cm) pooled areas. A pair of different-sized, shallow pools about five meters downchannel support Typha and other vegetation.

Figure 3. Left: Javelina Tank, sampling location 001 and orifice A, Saguaro National Park, April 2021. Right: Location of Javelina Tank below a bedrock cliff, with additional smaller tinajas in the channel below. NPS photos.

Site condition. In WY2021, the crew observed a moderate disturbance from drying, as two of the sampling locations were dry. Previously, drying had been rated as undisturbed or as a slight disturbance. No bullfrogs or crayfish (non-native, potentially invasive aquatic animals) were observed. However, the crew observed the three invasive plant species, all in scattered patches: red brome (Bromus rubens), crimson fountaingrass (Cenchrus setaceus), and rose natal grass (Melinis repens). These grass species were also present in WY2019.

The crew observed a single obligate/facultative wetland family: cattail (Typhaceae), which was also observed in WY2017–2019.

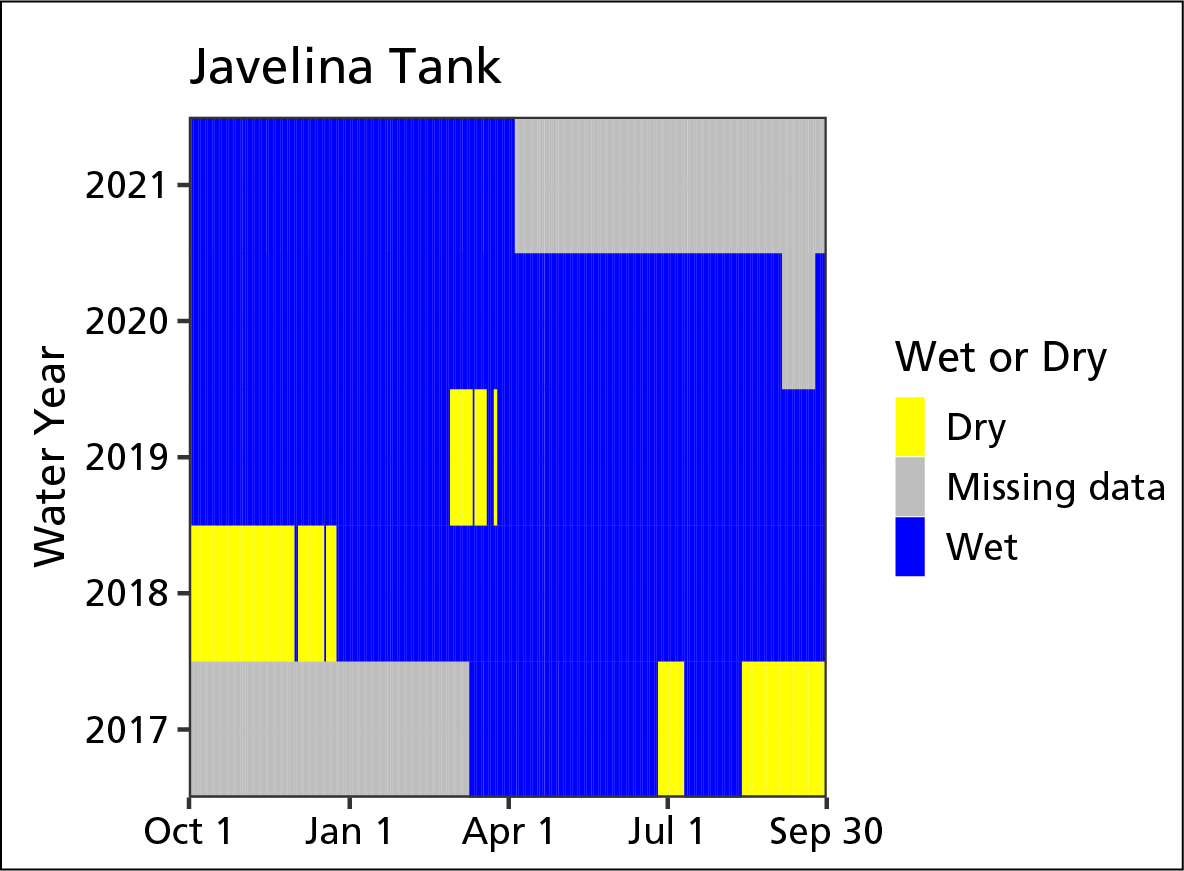

Figure 4. Water persistence in Javelina Tank, Saguaro National Park.

Figure 4. Water persistence in Javelina Tank, Saguaro National Park.Water quantity. The WY2021 visit occurred on April 5, 2021. The spring was wetted (contained water). Temperature sensors indicated that Javelina Tank was for wetted for all 187 days (100%) measured up to the WY2021 visit (Figure 4). In prior water years, the spring was wetted 69.1–100% of the days measured, with some missing data in WY2020.

Discharge was not measured in WY2021, and has never been measured during monitoring in Javelina Tank. Outflow has always been absent or too shallow for measurement during the sampling period in April.

Wetted extent was not measured in WY2021, as there was no springbrook. In the past, the system has been evaluated using a method for flowing water (Table 5).

Water quality. Core water-quality (Table 6) and water-chemistry (Table 7) data were collected at the primary sampling location. Specific conductivity, total dissolved solids, alkalinity, chloride, magnesium, and sulfate were lower than previous measurements. Dissolved oxygen was much lower than in WY2017–2019, indicating hypoxic conditions, likely due to decaying organic matter.

Table 5. Average width and depth (cm) of Javelina Tank within the springbrook length (up to 100 m) in WY2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Measurement | WY2021 value (Range of prior values)* | Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| Width (cm) | cns (117.4) | 2019 (1) |

| Depth (cm) | cns (0.9) | 2019 (1) |

| Length (m) | cns (54.7) | 2019 (1) |

*cns = could not sample.

Table 6. Data on core water-quality parameters for Javelina Tank in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location | WY2021 value (Range of prior values) |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | Center | 1.19 (9.12–11.43) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| pH | 001 | Center | 7.2 (7.59–8.64) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | Center | 126.8 (192.2–329) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | Center | 21.1 (14.1–30.9) | 2017–2019 (4) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | Center | 82 (124.8–213.8) | 2018–2019 (2) |

Table 7. Water-chemistry data (mg/L) for Javelina Tank in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location | WY2021 value (Range of prior values) |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkalinity (CaCO3) | 001 | Center | 35 (60–65) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| Calcium (Ca) | 001 | Center | 10 (12–24) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| Chloride (Cl) | 001 | Center | 0 (2–9) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 001 | Center | bdl* (5–12) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| Potassium (K) | 001 | Center | 3.2 (1–1.5) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| Sulphate (SO4) | 001 | Center | 0 (15–40) | 2017–2019 (3) |

*bdl = below detection limit.

Wild 10G Tinaja

Wild 10G (Figure 5) is a tinaja (small pool in rock basin) located within a complex of tinajas in Wildhorse Canyon. When characterized in WY2017, there were four wetted locations within 50 meters (164 ft) of Wild 10G Tinaja.

Figure 5. Left: Wild 10G Tinaja, sampling location 001 and orifice A, Saguaro National Park, April 2021. Right: Wild10G is located in a complex of tinajas in Wildhorse Canyon. NPS photos.

Site condition. In WY2021, the crew observed slight disturbance from drying and noted that there was no discharge from the outflow of the tinaja. This was the first observation of drying disturbance at Wild 10G Tinaja. No bullfrogs or crayfish (non-native, potentially invasive aquatic animals) were observed. However, the crew observed three invasive plant species, all in scattered patches: red brome (Bromus rubens), crimson fountaingrass (Cenchrus setaceus) and rose natal grass (Melinis repens). These grass species were also present in at least one prior visit during WY2017–2019.The crew did not observe any obligate/facultative wetland species, genera, or families. In prior years, the crew observed the forb, monkeyflower (Mimulus sp.).

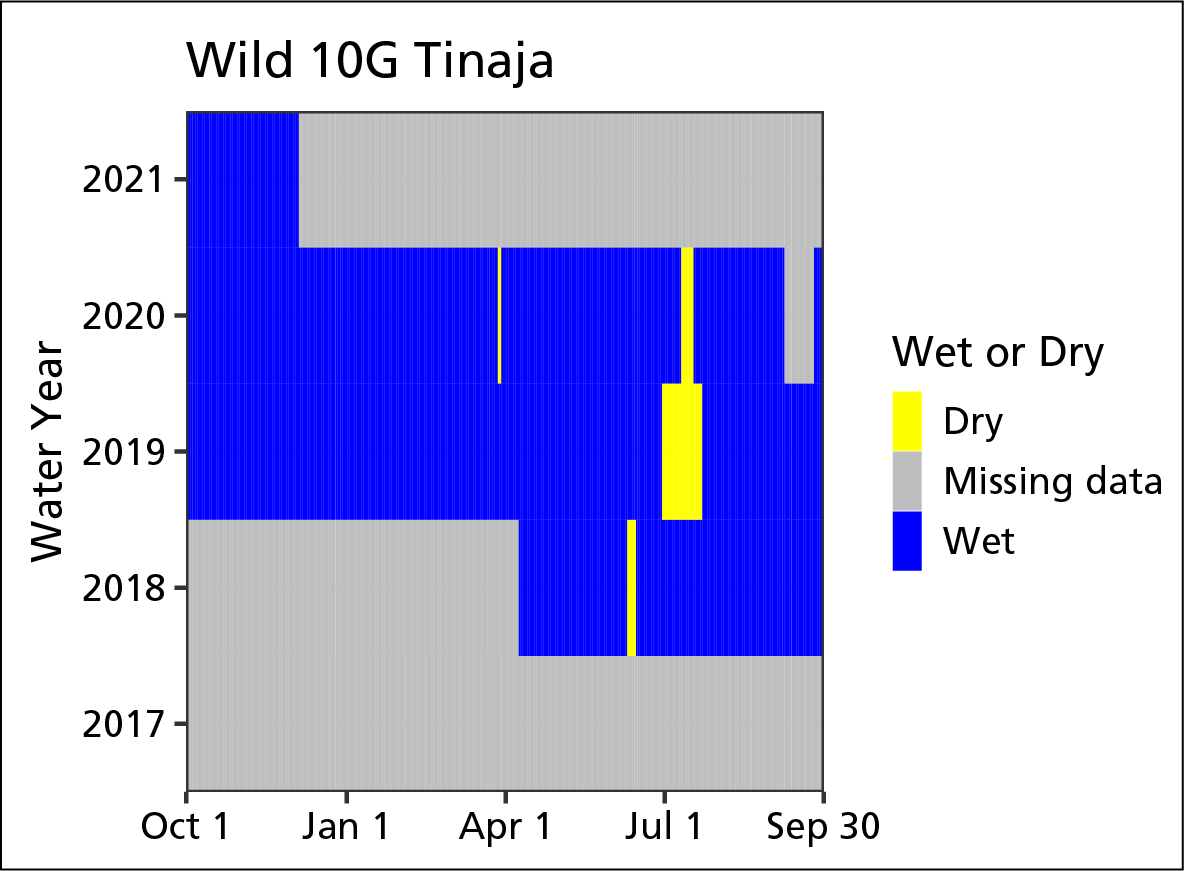

Figure 6. Water persistence in Wild 10G Tinaja, Saguaro National Park.>

Figure 6. Water persistence in Wild 10G Tinaja, Saguaro National Park.>Water quantity. The WY2021 visit occurred on April 7, 2021. The spring was wetted (contained water). Temperature sensors indicated that Wild 10G Tinaja was wetted for all 65 days (100%) measured (Figure 6). The sensors failed two months into WY2021. In prior water years, the spring was wetted 93.7–97.4% of the days measured.

Discharge was not measured in WY2021, because there was no outflow. Discharge was most recently measured in WY2018 (Table 8).

Wetted extent was evaluated using a method for standing water. Width averaged 290 centimeters (114.2 in), length averaged 148.7 centimeters (58.5 in), and depth averaged 48.2 centimeters (19 in) (Table 9). The width was somewhat smaller than previous measurements, whereas depth and length were comparable to WY2018–2019.

Water quality. Core water-quality (Table 10) and water-chemistry (Table 11) data were collected at the primary sampling location. Dissolved oxygen and pH were higher than in previous years, while temperature and total dissolved solids were lower. While there are no water-quality standards specific to Wild 10G Tinaja or most other springs in Sonoran Desert parks, pH in WY2021 exceeded the Arizona water-quality standard (6.5–9.0) for full- and partial- body contact (humans), and aquatic and wildlife designated uses for other surface waters (rivers, streams, lakes, and reservoirs). Most other chemical parameters were not within the range of prior years, but the slight differences were generally within the minimum detection limit of the instrument.

Table 8. Discharge data (L/min; mean ± SD) for Wild 10G in water year 2021, and values from prior years.

| Sampling location | WY2021 value (Prior value) | Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| 003 | cns* (1.1) | 2018 (1) |

*cns = could not sample.

Table 9. Average (± SD) width, length, and depth (cm) of Wild 10G in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Measurement | WY2021 value (Range of prior values) | Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| Width (cm) | 290 ± 42 (398.4–484.7) | 2018–2019 (2) |

| Depth (cm) | 48.2 ± 1.8 (39–45.2) | 2018–2019 (2) |

| Length (cm) | 148.7 ± 12.7 (147.6–170.2) | 2018–2019 (2) |

Table 10. Data on core water-quality parameters for Wild 10G in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location | WY2021 value (Range of prior values) |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | Center | 12.47 (8.44) | 2018 (1) |

| pH | 001 | Center | 10.08 (8.06–9.34) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | Center | 182.7 (191.4–340.7) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | Center | 16.4 (18–20.4) | 2017–2019 (4) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | Center | 119 (124.2–221.7) | 2017–2019 (3) |

Table 11. Water-chemistry data (mg/L) for Wild 10G in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location | WY2021 value (Range of prior values)* |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkalinity (CaCO3) | 001 | Center | 125 (60–125) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| Calcium (Ca) | 001 | Center | 26 (14–18) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| Chloride (Cl) | 001 | Center | bdl* (2–13) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 001 | Center | bdl* (3–16) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| Potassium (K) | 001 | Center | 3 (0.3–1.8) | 2017–2019 (3) |

| Sulphate (SO4) | 001 | Center | 8 (0–1) | 2017–2019 (3) |

*bdl = below detection limit.

Results for Water Year 2021 at High-Elevation Springs

Boulder | Bulrush | Cabin | Deer Head | Italian | Manna Grass | Manning Camp | Mica Meadows | Mud Hole | New Spring 3 | Spud Rock | Upper Joaquin

Boulder Spring

Boulder Spring (Figure 7) was first measured and characterized in WY2021. Boulder Spring is a rheocrene spring (emerges as a flowing stream) located on the east-facing slopes of the Rincon Mountains below Reef Rock within a deep drainage. Although the spring was not flowing when sampled, past work by park staff indicates that normally it emerges from under the roots of a ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) within the drainage. The channel continues, lined with large rocks and some facultative/obligate wetland plants that occur for approximately 25 meters.

Figure 7. Boulder Spring at Saguaro National Park, May 2021. NPS photo.

Site condition. The crew noted drying, fire, and windthrow as causing slight disturbance. The spring was unexpectedly dry. The crew observed numerous charred and dead-and-downed trees along the drainage. Neither bullfrogs nor crayfish (non-native, potentially invasive aquatic animals) were observed, nor any invasive plants. The crew observed the following obligate/facultative wetland species/genera/families: fowl mannagrass (Glyceria striata), bulrush (Scirpus sp.), rush family (Juncaceae), and sedge family (Cyperaceae).

Water quantity. The WY2021 visit occurred on May 29, 2021. The spring was dry. Temperature sensors were deployed on that date for the first time. Data will be reported during the next monitoring period. Neither discharge nor wetted extent was measured because the spring was dry.

Water quality. Water-quality data were not collected because the spring was dry.

Bulrush Spring

Bulrush Spring (Figure 8) was first sampled and characterized in WY2021. Bulrush Spring is a rheocrene spring (emerges as a flowing stream) located on the east-facing slope of the Rincon Mountains below Heartbreak Ridge. The water emerges as a small (<0.5 × 5-m) stagnant pool, then continues as a slightly wetted channel within a deep drainage. The channel has a series of small pools in bedrock. In 2021, the channel terminated at the largest pool along the break (~2 m wide and 20 cm deep). There was a negligible flow throughout the spring.

Figure 8. Bulrush Spring at Saguaro National Park, May 2021. NPS photo.

Site condition. In WY2021, the crew observed that Bulrush Spring was slightly disturbed by fire, with charring on trees, some with their lower branches burned off. No bullfrogs or crayfish (non-native, potentially invasive aquatic animals) were observed, nor were invasive plants detected. The crew observed the following obligate/facultative wetland species/genera/families: bulrush (Scirpus sp.), rush family (Juncaceae) and sedge family (Cyperaceae).

Water quantity. The WY2021 visit occurred on May 28, 2021. The spring was wetted. Temperature sensors were not deployed, so there is no estimate of persistence. Discharge could not be measured in WY2021 due to negligible surface flow throughout the springbrook. Wetted extent was evaluated using a method for flowing water. The total brook length was 21 meters (68.9 ft). Width and depth averaged 27.4 centimeters (10.8 in) and 1 centimeter (0.4 in), respectively (Table 12).

Water quality. Core water-quality (Table 13) and water-chemistry (Table 14) data were collected at the primary sampling location. This was the first year the Sonoran Desert Network collected data at Bulrush Spring. While there are no water-quality standards specific to Bulrush or most other springs in Sonoran Desert parks, pH in WY2021 exceeded the Arizona water-quality standard (6.5–9.0) for full- and partial- body contact (humans), and aquatic and wildlife designated uses, for other surface waters (rivers, streams, lakes, and reservoirs).

Table 12. Average (± SD) width and depth (cm) of Bulrush Spring within springbrook length (up to 100 m) in water year 2021, the first year of sampling.

| Measurement | WY2021 value (Range of prior values) | Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| Width (cm) | 27.4 ± 40.8 (none) | none (0) |

| Depth (cm) | 1 ± 1.4 (none) | none (0) |

| Length (m) | 21 (none) | none (0) |

Table 13. Data on core water-quality parameters for Bulrush Spring in water year 2021, the first year of sampling.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location | WY2021 value (Range of prior values) |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | Center | 5.46 (none) | none (0) |

| pH | 001 | Center | 6.21 (none) | none (0) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | Center | 99 (none) | none (0) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | Center | 26.5 (none) | none (0) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | Center | 64 (none) | none (0) |

Table 14. Water-chemistry data (mg/L) for Bulrush Spring in water year 2021, the first year of sampling.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location | WY2021 value (Range of prior values) |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkalinity (CaCO3) | 001 | Center | 35 (none) | none (0) |

| Calcium (Ca) | 001 | Center | 6 (none) | none (0) |

| Chloride (Cl) | 001 | Center | 9 (none) | none (0) |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 001 | Center | 6 (none) | none (0) |

| Potassium (K) | 001 | Center | 2.1 (none) | none (0) |

| Sulphate (SO4) | 001 | Center | 1 (none) | none (0) |

Cabin Spring

Cabin Spring (Figure 9) was first sampled and characterized in WY2021. Cabin Spring is a rheocrene spring (emerges as a flowing stream). The orifice, which appears to be a former springbox (a structure designed to impound springwater for human use) is a 1 × 1.5-m pool. Saturated black and grey silty soils comprise the substrate and extend 3–5 meters downslope from the springbox.

Figure 9. Cabin Spring at Saguaro National Park, May 2021. NPS photo.

Site condition. In WY2021, the crew observed moderate disturbance from wildlife, as evidenced by grazing of wetland plants along the wetted channel and many tracks including deer, raccoon and ringtail. Flow modification was rated as a slight disturbance because the orifice appeared to have been developed and maintained in the past as a springbox. No bullfrogs or crayfish (non-native, potentially invasive aquatic animals) were observed. Common dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) was the only invasive plant species observed, but its density was not recorded.

The crew observed the following obligate/facultative wetland genera/families: sedge (Carex sp.), spikerush (Eleocharis sp.), and rush family (Juncaceae).

Water quantity. The WY2021 visit occurred on May 28, 2021. The spring was wetted. Temperature sensors were deployed on that date but the data have not yet been downloaded and analyzed. Discharge was not measured because the crew did not observe surface flow.

Wetted extent was evaluated using a method for flowing water. The total brook length was 2 meters (7 ft). Width and depth averaged 62.3 centimeters (24.5 in) and 1.8 centimeters (0.7 in), respectively (Table 15).

Water quality. Core water-quality (Table 16) and water-chemistry (Table 17) data were collected at the primary sampling location. Water year 2021 was the first year of data collection. While there are no water quality standards specific to Cabin Spring or most other springs in Sonoran Desert parks, pH in WY2021 exceeded the Arizona water-quality standard (6.5–9.0) for full- and partial-body contact (humans), and aquatic and wildlife designated uses, for other surface waters (rivers, streams, lakes, and reservoirs). Low dissolved oxygen values indicated hypoxic conditions, likely due to decaying organic matter in the orifice that was noted by the crew.

Table 15. Average (± SD) width and depth (cm) of Cabin Spring within springbrook length (up to 100 m) in water year 2021, the first year of sampling.

| Measurement | WY2021 value (Range of prior values) | Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| Width (cm) | 62.3 ± 28.1 (none) | none (0) |

| Depth (cm) | 1.8 ± 0.9 (none) | none (0) |

| Length (m) | 2.4 (none) | none (0) |

Table 16. Data on core water-quality parameters for Cabin Spring in water year 2021, the first year of sampling.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location | WY2021 value (Range of prior values) |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | Center | 2.13 (none) | none (0) |

| pH | 001 | Center | 6.37 (none) | none (0) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | Center | 136.9 (none) | none (0) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | Center | 19.1 (none) | none (0) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | Center | 89 (none) | none (0) |

Table 17. Water-chemistry data (mg/L) for Cabin Spring in water year 2021, the first year of sampling.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location | WY2021 value (Range of prior values) |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkalinity (CaCO3) | 001 | Center | 35 (none) | none (0) |

| Calcium (Ca) | 001 | Center | 4 (none) | none (0) |

| Chloride (Cl) | 001 | Center | 0 (none) | none (0) |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 001 | Center | bdl* (none) | none (0) |

| Potassium (K) | 001 | Center | 1.8 (none) | none (0) |

| Sulphate (SO4) | 001 | Center | 1 (none) | none (0) |

*bdl = below detection limit.

Deer Head Spring

Deer Head Spring (Figure 10) is a rheocrene spring (emerges as a flowing stream) located on east-facing slopes of the Rincon Mountains. When characterized in WY2019, it emerged across the bottom of a gently sloping drainage, saturating the soil and eventually collecting and flowing through small, shallow pools and diverse channels into a flowing springbrook. While the site had a distinct channel downstream, there was no clear orifice or origin point. However, there was a small pool near the adjacent hiking trail. Park staff have speculated that the channel was cleared and maintained to provide water for people and packstock until 1976, when the Saguaro Wilderness was established and maintenance ceased. Sediment subsequently filled the springbrook, although the crew observed evidence of animals and/or hikers digging a small area for water to collect near the trail.

Figure 10. Deer Head Spring at Saguaro National Park, May 2021. NPS photo.

Site condition. In WY2021, the crew rated the spring as highly disturbed by drying because the spring was completely dry. The spring was also slightly disturbed by nearby hiking trails, recent flooding, and windthrow (branches strewn around). This was the first year that disturbance by drying and recent flooding were noted. No bullfrogs or crayfish (non-native, potentially invasive aquatic animals) were observed. However, the crew observed Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), an invasive plant, in scattered patches. The species was also observed in WY2019–2020 but in higher densities (evenly distributed patches). The crew observed the following obligate/facultative wetland genera/families: bulrush (Scirpus sp.), sedge (Carex sp.), and rush family (Juncaceae). All three were also observed in WY2019–2020.

Water quantity. The WY2021 visit occurred on May 29, 2021. The spring was dry. Sensors are not deployed at this spring due to logistical constrains at the site.

Discharge was not measured in WY2021 and has never been measured at the spring. There was no discernible flow in WY2019 or 2020.

Wetted extent was not measured in WY2021 (dry). It has only been measured in WY2019, as Deer Head Spring was dry in WY2020 (Table 18).

Water quality. Neither core water-quality (Table 19) nor water-chemistry (Table 20) data were collected in WY2021 (dry location). Both types of data were collected only in WY2019 due to dry conditions in WY2020.

Table 18. Average (± SD) width and depth (cm) of Deer Head Spring within springbrook length (up to 100 m), water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Measurement | WY2021 value (Range of prior values)* | Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| Width (cm) | cns (27.5) | 2019 (1) |

| Depth (cm) | cns (0.9) | 2019 (1) |

| Length (m) | cns (13.5) | 2019 (1) |

*cns = could not sample.

Table 19. Data on core water-quality parameters for Deer Head Spring in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location (Width/Depth) |

WY2021 value (Range of prior values)* |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (3.3) | 2019 (1) |

| pH | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (6.5) | 2019 (1) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (109) | 2019 (1) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (15.4) | 2019 (2) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (cns) | none (0) |

*cns = could not sample.

Table 20. Water-chemistry data (mg/L) for Deer Head Spring in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location (Width/Depth) |

WY2021 value (Range of prior values)* |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkalinity (CaCO3) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (35) | 2019 (1) |

| Calcium (Ca) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (4) | 2019 (1) |

| Chloride (Cl) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (0) | 2019 (1) |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (3) | 2019 (1) |

| Potassium (K) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (0.4) | 2019 (1) |

| Sulphate (SO4) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (4) | 2019 (1) |

*cns = could not sample.

Italian Spring

Italian Spring (Figure 11) was characterized in WY2018 as a rheocrene spring (emerges as a flowing stream) that emerged as a cool, clear pool on a hillslope. It formed a shallow channel of moist soil, rather than a flowing springbrook, that continued downstream for at least 100 meters (328 ft), but no measurable surface water occurred beyond 10 meters (32.8 ft) from the pool.

Figure 11. Italian Spring at Saguaro National Park, May 2021. NPS photo.

Site condition. In WY2021, the spring was moderately disturbed by nearby hiking trails and drying (small amount of water). This was the first year drying was noted. The crew recorded slight disturbance for contemporary human use, flow modification, fire, and windthrow, as and evidenced from the trail, historic excavation, and nearby areas with indications of fire or downed trees. No bullfrogs or crayfish (non-native, potentially invasive aquatic animals) were observed, nor were any invasive plants detected. The crew observed three obligate/facultative wetland species/genera/families, all of which were observed in WY2018–2020: fowl mannagrass (Glyceria striata), sedge (Carex sp.), and rush family (Juncaceae).

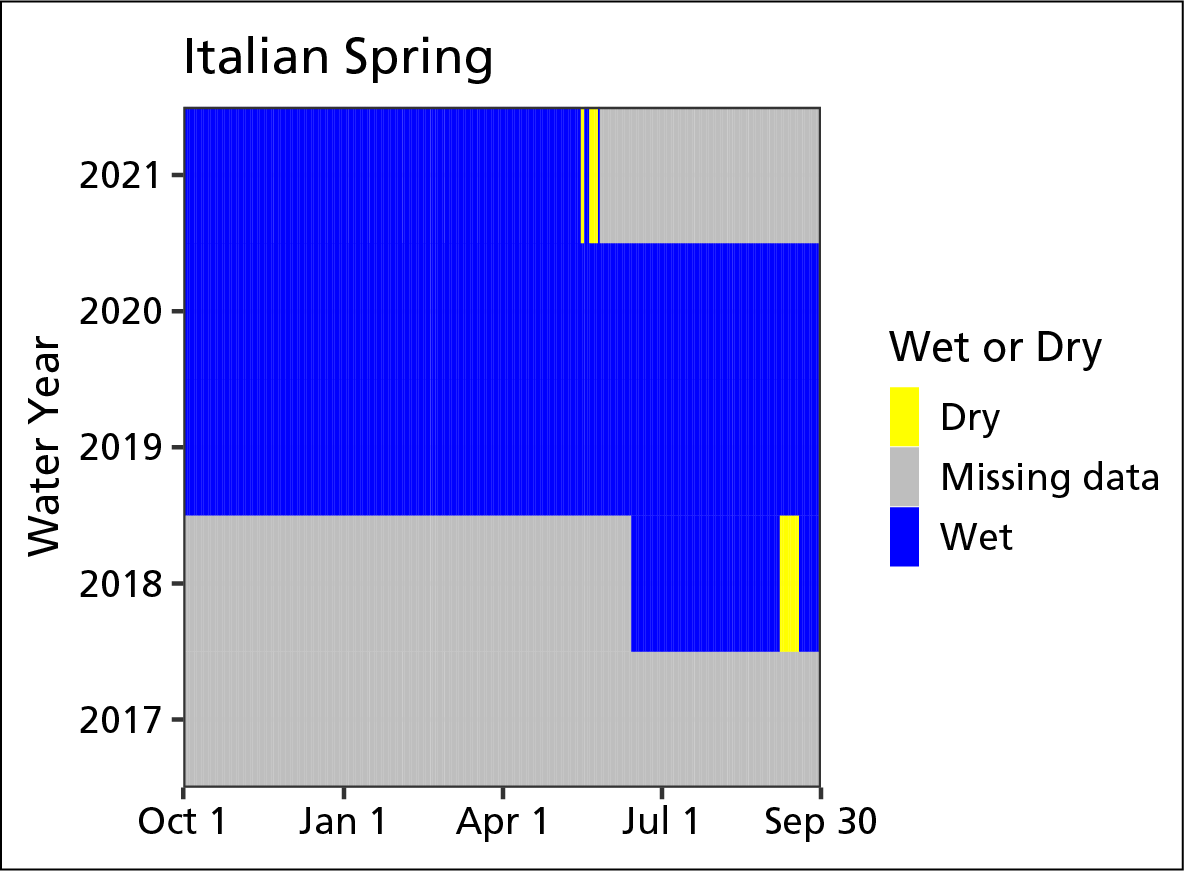

Figure 12. Water persistence in Italian Spring, Saguaro National Park.

Figure 12. Water persistence in Italian Spring, Saguaro National Park.Water quantity. The WY2021 visit occurred on May 27, 2021. The spring was wetted (contained water). Temperature sensors indicated that Italian Spring was wetted for 232 of 239 days (97.1%) measured up to the WY2021 visit (Figure 12). The water was ~2 × 3 × 1 centimeters at the WY2021 visit. The small amount of water is likely why temperature sensors indicated the spring was dry on the day of the WY2021 visit. In prior water years, the spring was wetted 89.8–100% of the days measured.

Discharge was not measured and has not been collected at the spring during any monitoring visit, as there has never been discernable surface flow.

Wetted extent was not measured in WY2021 because the amount of water was so small (Table 21). Wetted extent was measured using a method for flowing water in WY2018 and WY2020.

Water quality. Neither core water-quality nor water-chemistry data were collected in WY2021, due to insufficient water. In the past, core parameters were collected at different widths at the primary sampling location (Table 22). A single water-chemistry sample was collected in WY2018, 2019, and 2020 (Table 23).

Table 21. Average (± SD) width and depth (cm) of Italian Spring within springbrook length (up to 100 m), water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Measurement | WY2021 value (Range of prior values)* | Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| Width (cm) | cns (47.7–69.1) | 2018–2020 (3) |

| Depth (cm) | cns (0.4–3.1) | 2018–2020 (3) |

| Length (m) | cns (10.6–39) | 2018–2020 (3) |

*cns = could not sample.

Table 22. Data on core water-quality parameters for Italian Spring in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location (Width/Depth) | WY2021 value (Range of prior values)* |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | 25%/Center | cns (5.77) | 2019 (1) |

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | 50%/Center | cns (5.87) | 2019 (1) |

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | 75%/Center | cns (6.04) | 2019 (1) |

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | Center | cns (7.27) | 2020 (1) |

| pH | 001 | 25%/Center | cns (6.6) | 2019 (1) |

| pH | 001 | 50%/Center | cns (6.1) | 2019 (1) |

| pH | 001 | 75%/Center | cns (6) | 2019 (1) |

| pH | 001 | Center | cns (6.46–7.36) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | 25%/Center | cns (85) | 2019 (1) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | 50%/Center | cns (86) | 2019 (1) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | 75%/Center | cns (85) | 2019 (1) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | Center | cns (48.1–58.7) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | 25%/Center | cns (9.8) | 2019 (2) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | 50%/Center | cns (10.2) | 2019 (2) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | 75%/Center | cns (9.8) | 2019 (2) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | Center | cns (9.8–10.5) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | 25%/Center | cns (cns) | none (0) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | 50%/Center | cns (cns) | none (0) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | 75%/Center | cns (cns) | none (0) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | Center | cns (38.4) | 2018 (1) |

*cns = could not sample.

Table 23. Water-chemistry data (mg/L) for Italian Spring in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location | WY2021 value (Range of prior values)* |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkalinity (CaCO3) | 001 | Center | cns (10–20) | 2018–2020 (3) |

| Calcium (Ca) | 001 | Center | cns (2–4) | 2018–2020 (3) |

| Chloride (Cl) | 001 | Center | cns (1–5) | 2018–2020 (3) |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 001 | Center | cns (bdl–13)** | 2018–2020 (3) |

| Potassium (K) | 001 | Center | cns (0.4–0.9) | 2018–2020 (3) |

| Sulphate (SO4) | 001 | Center | cns (3–4) | 2018–2020 (3) |

*cns = could not sample. **bdl = below detection limit.

Manna Grass Spring

Manna Grass Spring (Figure 13) was first sampled and characterized in WY2021. Located on the north slope of the Rincon Mountains, Manna Grass Spring is a rheocrene spring (emerges as a flowing stream) situated in a mixed fir and pine forest that was burned in the Helen’s 2 Fire (2004). Water emerges from a dirt bank within a steep drainage. In 2021, the channel remained wetted and covered in downed vegetation for approximately 10 meters and then formed the first pool (Figure 1, left). From the pool, the channel continued with negligible flow across bedrock slabs, ending at a bedrock slide.

Figure 13. Manna Grass Spring at Saguaro National Park, May 2021. NPS photo.

Site condition. In WY2021, the crew recorded slight disturbance from contemporary human use (wildlife camera), fire (charred trees), and windthrow (branches strewn about). No bullfrogs or crayfish (non-native, potentially invasive aquatic animals) were observed. However, the crew observed 1–5 plants of Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), an invasive grass. The crew also observed the following obligate/facultative wetland species/genera/families: fowl mannagrass (Glyceria striata), monkeyflower (Mimulus sp.), sedge (Carex sp.), and sedge family (Cyperaceae).

Water quantity. The WY2021 visit occurred on May 31, 2021. The spring was wetted. Temperature sensors were first deployed on that date. Data will be reported in the next monitoring period.

Discharge was estimated at 0.3 (± 0.01) liters (0.1 ± 0.002 gal) per minute in WY2021 (Table 24).

Wetted extent was evaluated using a method for flowing water. The total brook length was 39 meters (128 ft). Width and depth averaged 21.5 centimeters (8.5 in) and 0.1 centimeters (0.01 in) (Table 25).

Water quality. Core water-quality (Table 26) and water-chemistry (Table 27) data were collected at the primary sampling location. Water year 2021 was the first year of data collection.

Table 24. Discharge data (L/min; mean ± SD) for Manna Grass Spring in water year 2021, and values from prior years.

| Sampling location | WY2021 value (Prior value) | Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| 003 | 0.3 ± 0.01 (none) | none (0) |

Table 25. Average (± SD) width and depth (cm) of Manna Grass Spring within springbrook length (up to 100 m) in water year 2021, and values from prior years.

| Measurement | WY2021 value (Prior value) | Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| Width (cm) | 21.5 ± 22.5 (none) | none (0) |

| Depth (cm) | 0.1 ± 0 (none) | none (0) |

| Length (m) | 39.3 (none) | none (0) |

Table 26. Data on core water-quality parameters for Manna Grass Spring in water year 2021, and values from prior years.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location | WY2021 value (Prior value) |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | Center | 8.31 (none) | none (0) |

| pH | 001 | Center | 7.52 (none) | none (0) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | Center | 121.5 (none) | none (0) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | Center | 8.3 (none) | none (0) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | Center | 79 (none) | none (0) |

Table 27. Water-chemistry data (mg/L) for Manna Grass Spring in water year 2021, and values from prior years.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location | WY2021 value (Prior value) | Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkalinity (CaCO3) | 001 | Center | 65 (none) | none (0) |

| Calcium (Ca) | 001 | Center | 12 (none) | none (0) |

| Chloride (Cl) | 001 | Center | 5 (none) | none (0) |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 001 | Center | 7 (none) | none (0) |

| Potassium (K) | 001 | Center | 0.7 (none) | none (0) |

| Sulphate (SO4) | 001 | Center | 0 (none) | none (0) |

Manning Camp Reservoir

Manning Camp Reservoir (Figure 14) was classified in WY2018 as a limnocrene spring (emerges as one or more still pools). It was described as a large pool at the head of Chimenea Canyon, modified with a small dam at Manning Camp. The water was warm and clear, with a film on the surface. There was no inflow, and one observable outflow was too small to measure. The substrate was small gravel, occasionally covered by dense patches of organic material. According to park managers, the substrate is periodically dredged to ensure adequate water capacity for supplying domestic water to Manning Camp.

Figure 14. Manning Camp Reservoir at Saguaro National Park, May 2021. NPS photo.

Site condition. In WY2021, the reservoir was highly disturbed by flow modification and contemporary human use due to its reservoir nature, springbox, and use as a water source. The site is also slightly disturbed by nearby hiking trails. These disturbances were observed in the past. No bullfrogs or crayfish (non-native, potentially invasive aquatic animals) were observed. However, the crew observed Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), an invasive plant, in scattered patches. The species was also observed in WY2020 in the same density. The crew also observed the following obligate/facultative wetland genera/families: bulrush (Scirpus sp.), monkeyflower (Mimulus sp.), sedge (Carex sp.), willow (Salix sp.), and rush family (Juncaceae). All genera/families observed in WY2021 were also observed at least twice since WY2018.

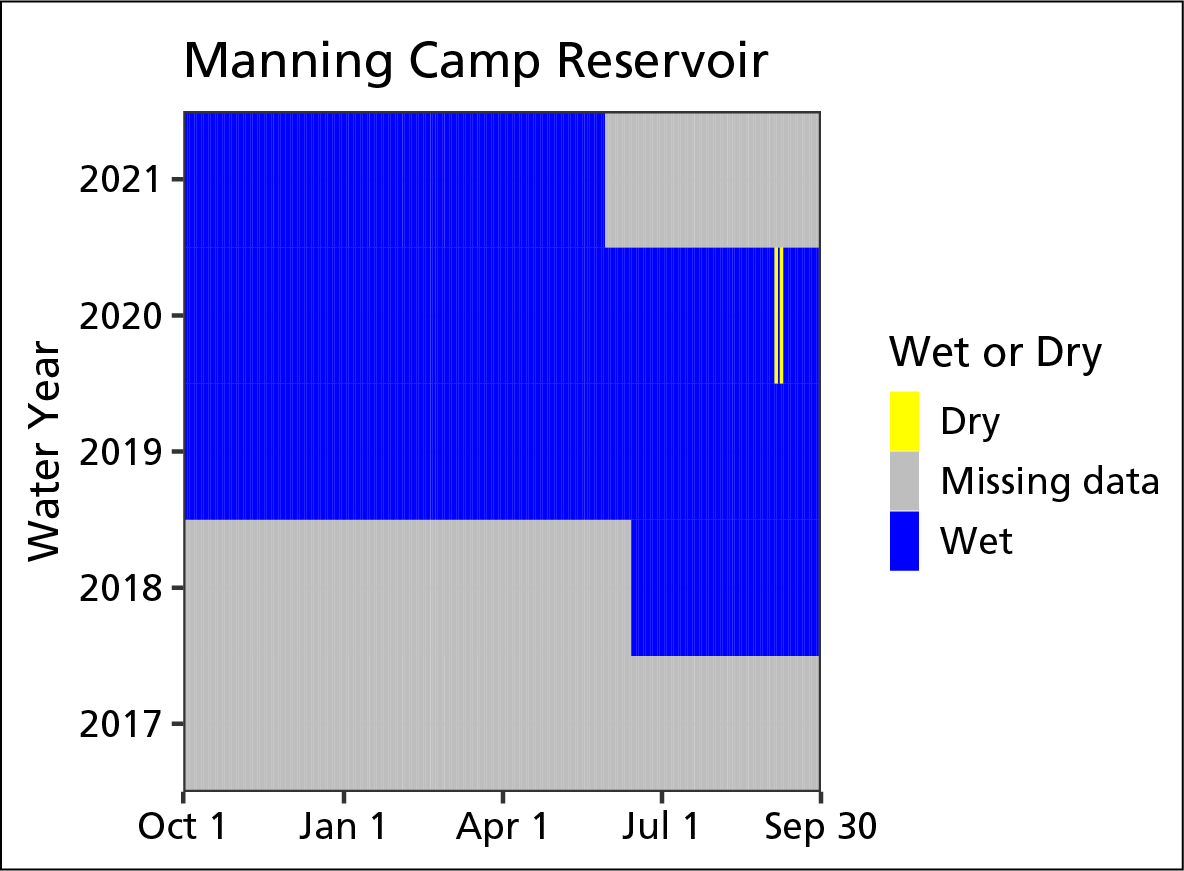

Figure 15. Water persistence in Manning Camp Reservoir, Saguaro National Park.

Figure 15. Water persistence in Manning Camp Reservoir, Saguaro National Park.Water quantity. The WY2021 visit occurred on May 30, 2021. The spring was wetted (contained water). Temperature sensors indicated that Manning Camp Reservoir was wetted for all 242 days (100%) measured up to the WY2021 visit (Figure 15). In prior water years, the spring was wetted 98.9–100% of the days measured.

Discharge was not measured and has not been measured in the past, as there was no outflow over the dam during the sampling period (May–June).

Wetted extent was evaluated using a method for standing water. Width averaged 1,401.7 centimeters (551.8 in); length averaged 1,063.3 centimeters (418.6 in) (Table 28). Depth was not measured, as it would have required entering—and potentially contaminating—the reservoir, which provides the drinking water for Manning Camp. The overall width and depth dimensions appeared similar to prior years, but the labeling of width vs. depth may have changed.

Water quality. Core water-quality data were collected at three depths (near surface, 1/3 below surface, 2/3 below surface) at the primary sampling location near the springbox (Table 29). In the past, only a single core water-quality measurement was taken, making comparisons difficult. Water-chemistry data were collected at the primary sampling location (Table 30). The values were similar to those of prior years. While there are no water-quality standards specific to Manning Camp Reservoir or most other springs in Sonoran Desert parks, pH in WY2021 slightly exceeded the Arizona water-quality standard (6.5–9.0) for full- and partial-body contact (humans), and aquatic and wildlife designated uses for other surface waters (rivers, streams, lakes, and reservoirs).

Table 28. Average (± SD) width, length, and depth (cm) of Manning Camp Reservoir in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Measurement | WY2021 value (Range of prior values) | Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| Width (cm) | 1,401.7 ± 239.5 (872.2–1,063.3) | 2018–2020 (3) |

| Depth (cm) | n/a* (13.6–32.3) | 2018–2020 (3) |

| Length (cm) | 1,063.3 ± 180.4 (1,299.8–1,753.3) | 2018–2020 (3) |

*n/a = not available

Table 29. Data on core water-quality parameters for Manning Camp Reservoir in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location (Width, Depth) |

WY2021 value (Range of prior values)* |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | Center | cns (5.45) | 2020 (1) |

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | Center, 1/3 | 5.99 (cns) | none (0) |

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | Center, 2/3 | 2.16 (cns) | none (0) |

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | Center, Bottom | 2.05 (cns) | none (0) |

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | Center, Surface | cns (4.98) | 2019 (1) |

| pH | 001 | Center | cns (5.98–7.23) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| pH | 001 | Center, Surface | cns (5.6) | 2019 (1) |

| pH | 001 | Center, 1/3 | 6.44 (cns) | none (0) |

| pH | 001 | Center, 2/3 | 6.3 (cns) | none (0) |

| pH | 001 | Center, Bottom | 6 (cns) | none (0) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | Center | cns (44.7–53) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | Center, 1/3 | 58 (cns) | none (0) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | Center, 2/3 | 57.8 (cns) | none (0) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | Center, Bottom | 53.8 (cns) | none (0) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | Center, Surface | cns (46) | 2019 (1) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | Center | cns (19.1–21.1) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | Center, 1/3 | 22.5 (cns) | none (0) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | Center, 2/3 | 13.1 (cns) | none (0) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | Center, Bottom | 11.5 (cns) | none (0) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | Center, Surface | cns (17.3) | 2019 (2) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | Center | cns (34.5) | 2018 (1) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | Center, 1/3 | 38 (cns) | none (0) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | Center, 2/3 | 38 (cns) | none (0) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | Center, Bottom | 41 (cns) | none (0) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | Center, Surface | cns (cns) | none (0) |

*cns = could not sample.

Table 30. Water-chemistry data (mg/L) for Manning Camp Reservoir in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location (Width/Depth) |

WY2021 value (Range of prior values)* |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkalinity (CaCO3) | 001 | Center | 15 (20–30) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Alkalinity (CaCO3) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (25) | 2019 (1) |

| Calcium (Ca) | 001 | Center | 8 (2–4) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Calcium (Ca) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (2) | 2019 (1) |

| Chloride (Cl) | 001 | Center | 0 (0–2) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Chloride (Cl) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (4) | 2019 (1) |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 001 | Center | 1 (bdl–4)** | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (4) | 2019 (1) |

| Potassium (K) | 001 | Center | 0.9 (0.3–1.2) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Potassium (K) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (0) | 2019 (1) |

| Sulphate (SO4) | 001 | Center | 0 (0–3) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Sulphate (SO4) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (0) | 2019 (1) |

*cns = could not sample. **bdl = below detection limit.

Mica Meadows Trail Seep 1

Mica Meadows Trail Seep 1 (Figure 16) was characterized in WY2019 as a rheocrene spring (emerges as a flowing stream) that emerged as a non-flowing pool along the bank of a drainage. The orifice emerged at a large bedrock slab beneath a hillslope. The surrounding drainage was a narrow, dry, streambed of cobble substrate.

Figure 16. Mica Meadows Trail Seep 1 at Saguaro National Park, May 2021. NPS photo.

Site condition. In WY2021, the crew rated the spring as highly disturbed by drying (spring was dry) and fire (sediment filled pools), and moderately disturbed by flooding (sediment). Water year 2021 was the first year drying and recent flooding were observed as disturbances. The spring was also slightly disturbed by nearby hiking trails, windthrow (dead and downed trees), and wildlife (grazing evidence). This was the first occurrence of windthrow disturbance. No bullfrogs or crayfish (non-native, potentially invasive aquatic animals) were observed, nor were any invasive plants detected. The crew observed the following obligate/facultative wetland genera/families: sedges (Carex sp.) and the sedge family (Cyperaceae). The sedge genera was observed in WY2018–2020.

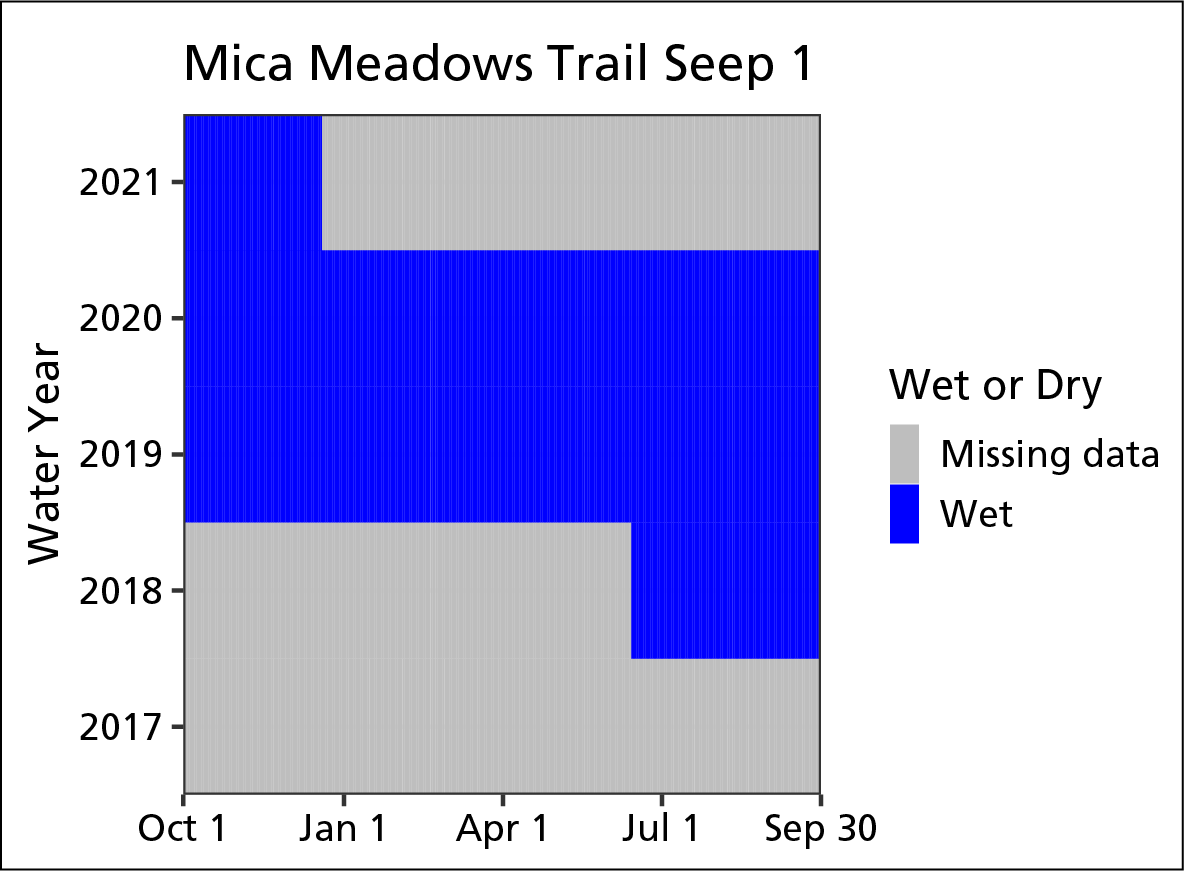

Figure 17. Water persistence in Mica Meadows Trail Seep 1, Saguaro National Park.

Figure 17. Water persistence in Mica Meadows Trail Seep 1, Saguaro National Park.Water quantity. The WY2021 visit occurred on May 30, 2021. The spring was dry. Temperature sensors indicated that Mica Meadows Trail Seep 1 was wetted (contained water) for 80 of 80 days (100%) measured in WY2021 until the sensors failed (Figure 17). During prior water years, the spring was wetted 100% of the days measured.

Discharge was not measured because the spring was dry. The only previous measurement of discharge was in WY2019, as flow was negligible in the other years (Table 31).

Wetted extent was not measured because the spring was dry. In WY2018 and WY2020, wetted extent was measured using a method for flowing water (Table 32).

Water quality. Core water-quality (Table 33) and water-chemistry (Table 34) data were not collected because the spring was dry.

Table 31. Discharge data (L/min; mean ± SD) for Mica Meadows Trail Seep 1 in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Sampling location | WY2021 value (Range of prior values)* | Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| 002 | cns (5.3) | 2019 (1) |

*cns = could not sample.

Table 32. Average (± SD) width and depth (cm) of Mica Meadows Trail Seep 1 within springbrook length (up to 100 m) in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Measurement | WY2021 value (Range of prior values)* | Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| Width (cm) | cns (42.4–174.8) | 2018–2020 (3) |

| Depth (cm) | cns (2–6.2) | 2018–2020 (3) |

| Length (m) | cns (1.4–18) | 2018–2020 (3) |

*cns = could not sample.

Table 33. Data on core water-quality parameters for Mica Meadows Trail Seep 1 in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location (Width/Depth) |

WY2021 value (Range of prior values)* |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | 25%/Center | cns (4.27) | 2019 (1) |

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | 50%/Center | cns (3.91) | 2019 (1) |

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | 75%/Center | cns (3.77) | 2019 (1) |

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | Center | cns (3.65) | 2020 (1) |

| pH | 001 | 25%/Center | cns (5.4) | 2019 (1) |

| pH | 001 | 50%/Center | cns (5.5) | 2019 (1) |

| pH | 001 | 75%/Center | cns (5.9) | 2019 (1) |

| pH | 001 | Center | cns (5.44–7.15) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | 25%/Center | cns (52) | 2019 (1) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | 50%/Center | cns (54) | 2019 (1) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | 75%/Center | cns (51) | 2019 (1) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | Center | cns (57.7–81.4) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | 25%/Center | cns (9.4) | 2019 (2) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | 50%/Center | cns (9.1) | 2019 (2) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | 75%/Center | cns (8.9) | 2019 (2) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | Center | cns (9.9–11.5) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | 25%/Center | cns (cns) | none (0) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | 50%/Center | cns (cns) | none (0) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | 75%/Center | cns (cns) | none (0) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | Center | cns (56.6) | 2018 (1) |

*cns = could not sample.

Table 34. Water-chemistry data (mg/L) for Mica Meadows Trail Seep 1 in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location (Width/Depth) |

WY2021 value (Range of prior values)* |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkalinity (CaCO3) | 001 | Center | cns (15–20) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Alkalinity (CaCO3) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (20) | 2019 (1) |

| Calcium (Ca) | 001 | Center | cns (0–4) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Calcium (Ca) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (11) | 2019 (1) |

| Chloride (Cl) | 001 | Center | cns (0–14) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Chloride (Cl) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (2) | 2019 (1) |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 001 | Center | cns (bdl–9)** | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (11) | 2019 (1) |

| Potassium (K) | 001 | Center | cns (2.4–2.6) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Potassium (K) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (0.3) | 2019 (1) |

| Sulphate (SO4) | 001 | Center | cns (0–5) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Sulphate (SO4) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (0) | 2019 (1) |

*cns = could not sample. **bdl = below detection limit.

Mud Hole Spring

Mud Hole Spring (Figure 18) was characterized in WY2018 as a rheocrene spring (emerges as a flowing stream) that occurred on a hillslope rather than within a drainage. The cool, clear discharge emerged into a small, human-developed, rock-lined pool. Immediately below the pool, the springbrook formed a shallow, narrow channel with low velocity before subsiding into channel sediment. The substrate in both the pool and springbrook was small gravel. This site had been developed, as evidenced by the lining of the orifice pool with rocks.

Figure 18. Mud Hole Spring at Saguaro National Park, May 2021. NPS photo.

Site condition. In WY2021, the crew rated the site as moderately disturbed by contemporary human use, as evidenced by footprints around the spring. Nearby hiking trails, drying (less productive), and wildlife (scat and tracks) all caused slight disturbance. This was the first year drying was noted at the spring. The other types of disturbance had been previously observed. No bullfrogs or crayfish (non-native, potentially invasive aquatic animals) were observed, nor were any invasive plants detected. The crew observed the following obligate/facultative wetland genera/families: spikerush (Eleocharis sp.) and rush family (Juncaceae). Both were observed in WY2018–2020.

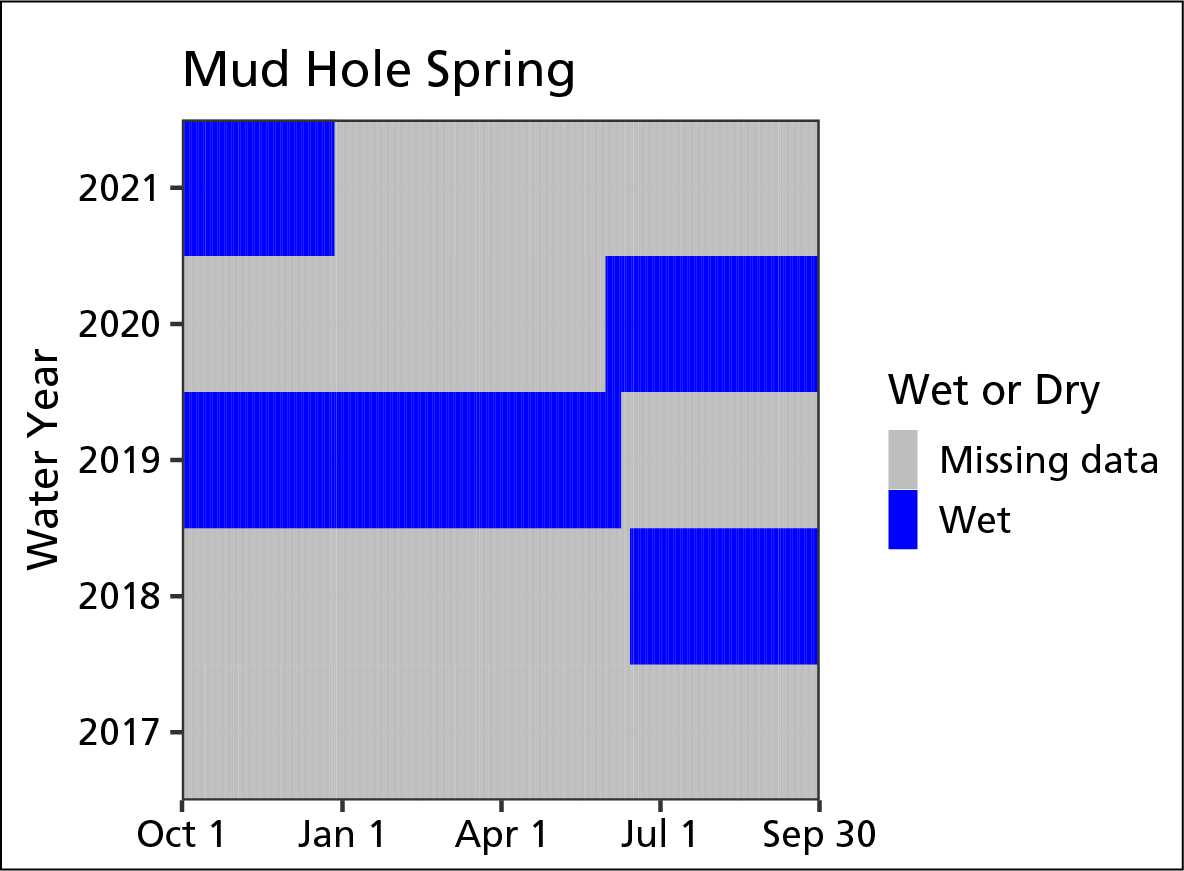

Figure 19. Water persistence in Mud Hole Spring, Saguaro National Park.>

Figure 19. Water persistence in Mud Hole Spring, Saguaro National Park.>Water quantity. The WY2021 visit occurred on May 29, 2021. The spring was wetted (contained water). Temperature sensors indicated that Mud Hole Spring was wetted for 88 of 88 days (100%) measured from the start of WY2021 until the sensor failed (Figure 19). In prior water years, the spring was wetted 100% of the days measured.

Discharge was estimated at 0.3 (± 0.03) liters (0.1 ± 0.01 gal) per minute in WY2021 (Table 35). This was similar to discharge measured in WY2018–2020.

Wetted extent was evaluated using a method for flowing water. The total brook length was 11 meters (36 ft). Width and depth averaged 25.1 centimeters (9.9 in) and 1.6 centimeters (0.6 in), respectively. The averages in WY2021 were similar to those in WY2018–2020 (Table 36).

Water quality. Core water-quality (Table 37) and water-chemistry (Table 38) data were collected at the primary sampling location. Measurements were generally similar to those from prior years.

Table 35. Discharge data (L/min; mean ± SD) for Mud Hole Spring in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Sampling location | WY2021 value (Range of prior values) | Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| 002 | 0.3 ± 0.03 (0.2–0.3) | 2018–2020 (3) |

Table 36. Average (± SD) width and depth (cm) of Mud Hole Spring within springbrook length (up to 100 m) in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Measurement | WY2021 value (Range of prior values) | Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| Width (cm) | 25.1 ± 15.4 (19.7–37.4) | 2018–2020 (3) |

| Depth (cm) | 1.6 ± 2 (0.6–2) | 2018–2020 (3) |

| Length (m) | 11.2 (9–11.9) | 2018–2020 (3) |

Table 37. Data on core water-quality parameters for Mud Hole Spring in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location (Width/Depth) | WY2021 value (Range of prior values)* |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | Center | 4.63 (3.21) | 2020 (1) |

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (3.49) | 2019 (1) |

| pH | 001 | Center | 6.72 (6.36–7.29) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| pH | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (6.2) | 2019 (1) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | Center | 166.4 (171.4–174.4) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (191) | 2019 (1) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | Center | 14.2 (14.6–16.3) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (16.6) | 2019 (2) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | Center | 108 (113.1) | 2018 (1) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (cns) | none (0) |

*cns = could not sample.

Table 38. Water-chemistry data (mg/L) for Mud Hole Spring in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location (Width/Depth) |

WY2021 value (Range of prior values)* |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkalinity (CaCO3) | 001 | Center | 80 (75–95) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Alkalinity (CaCO3) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (65) | 2019 (1) |

| Calcium (Ca) | 001 | Center | 10 (8–10) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Calcium (Ca) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (12) | 2019 (1) |

| Chloride (Cl) | 001 | Center | 9 (4–16) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Chloride (Cl) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (2) | 2019 (1) |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 001 | Center | 9 (bdl–8)** | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (6) | 2019 (1) |

| Potassium (K) | 001 | Center | 1.5 (1–1.9) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Potassium (K) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (0.5) | 2019 (1) |

| Sulphate (SO4) | 001 | Center | 6 (0–4) | 2018–2020 (2) |

| Sulphate (SO4) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (0) | 2019 (1) |

*cns = could not sample. **bdl = below detection limit.

New Spring 3

This rheocrene spring (emerges as a flowing stream) was characterized in WY2019 as emerging from a low-angle drainage at an area of exposed bedrock (Figure 20). Orifice A was a small, shallow pool that flowed down a bedrock pouroff. The orifice was sheltered by soil, rock, and woody debris on three sides. The water in the pool was clear, with a fine gravel substrate. There were numerous aquatic insects in the pool. Upslope of the orifice was a meadow of riparian obligates, including fowl mannagrass (Glyceria striata), monkeyflower (Mimulus sp.), and sedge (Carex sp.). There were a few damp patches of soil within the meadow, but no surface water.

Figure 20. New Spring 3 at Saguaro National Park, May 2021. NPS photo.

Site condition. In WY2021, the crew rated the site as highly disturbed by drying (no surface water present) and fire (recent fire in the area). These were the highest disturbance ratings in these categories since monitoring began in WY2019. The site was also moderately disturbed by nearby hiking trails and contemporary human use (cut trees); both types of disturbance were previously noted at the spring. Similar to prior years, the site was also rated as slightly disturbed by recent flooding (sedimentation), wildlife (grazing), and windthrow (dead and down trees). No bullfrogs or crayfish (non-native, potentially invasive aquatic animals) were observed, nor were any invasive plants detected. The crew observed the following obligate/facultative wetland genera/families, all of which were also present in WY2020: sedge (Carex sp.), sedge family (Cyperaceae), and rush family (Juncaceae).

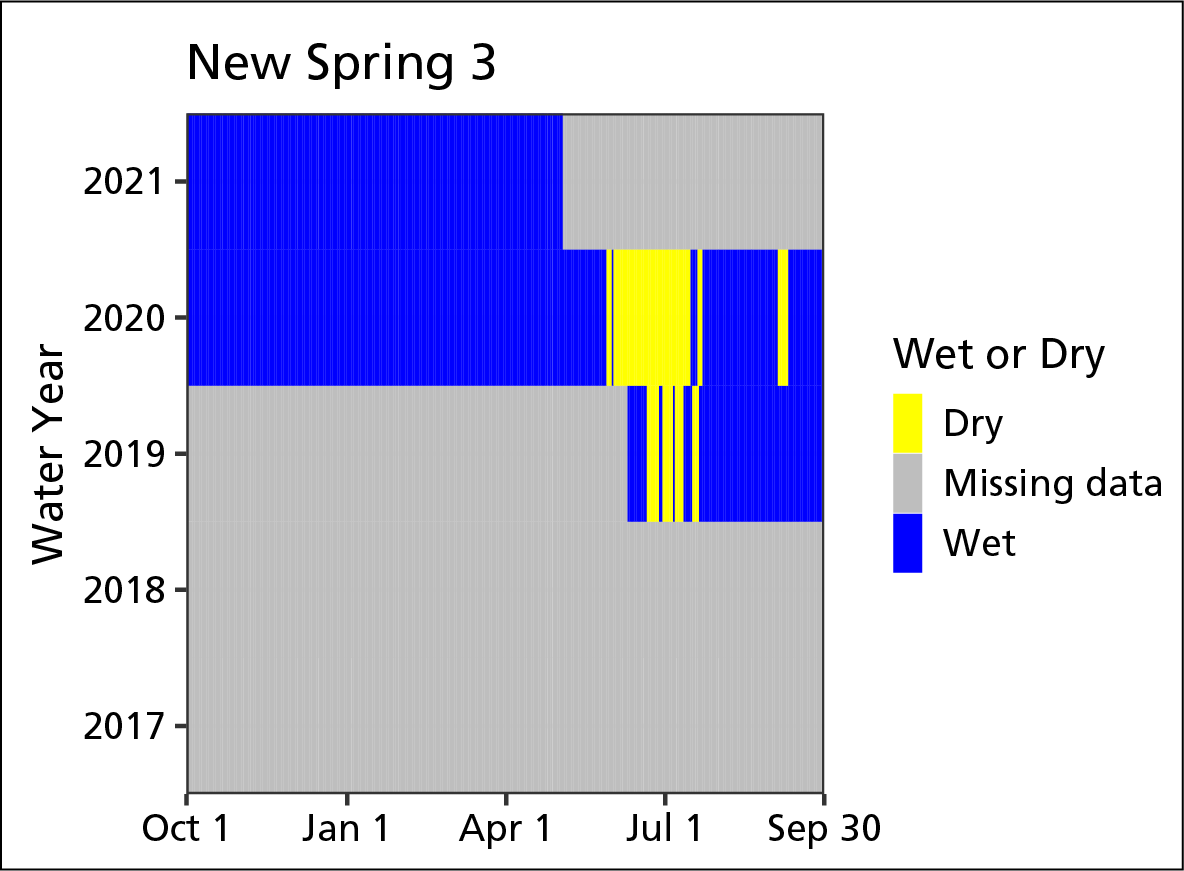

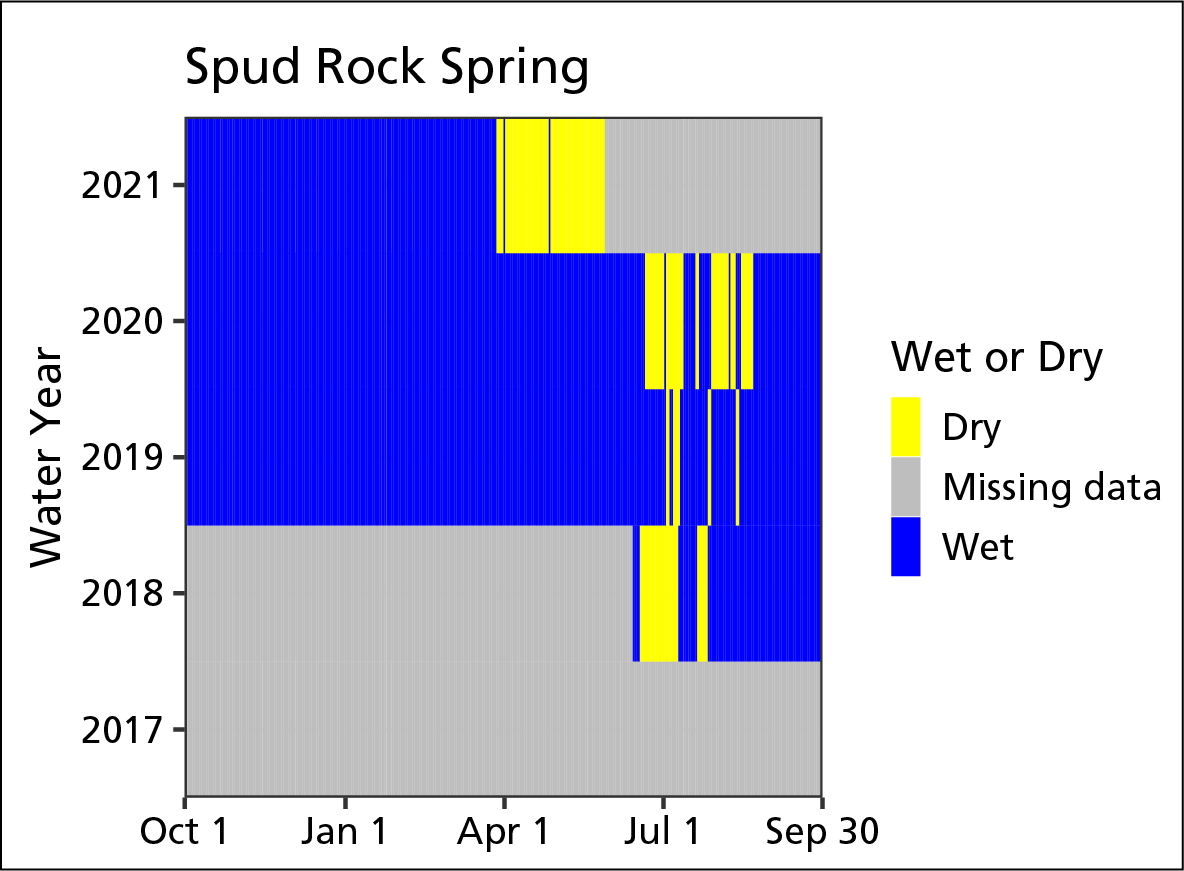

Figure 21. Water persistence in New Spring 3, Saguaro National Park.

Figure 21. Water persistence in New Spring 3, Saguaro National Park.Water quantity. The WY2021 visit occurred on May 30, 2021. The spring was dry. However, temperature sensors indicated that New Spring 3 was wetted (contained water) for all 216 days (100%) measured up to the WY2021 visit (Figure 21). This suggests that some of the wetted days were false positives. In prior water years, the spring was wetted 80.4–84.7% of the days measured.

Discharge and wetted extent were not measured in WY2021 because the spring was dry (Tables 39 and 40).

Water quality. Core water-quality and water-chemistry data were not collected in WY2021 because the spring was dry (Tables 41 and 42).

Table 39. Discharge data (L/min; mean ± SD) for New Spring 3 in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Sampling location | WY2021 value (Range of prior values) | Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| 003 | cns* (0.2–0.4) | 2019–2020 (2) |

*cns = could not sample.

Table 40. Average (± SD) width and depth (cm) of New Spring 3 within springbrook length (up to 100 m) in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Measurement | WY2021 value (Range of prior values) | Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| Width (cm) | cns (44.1–46.7) | 2019–2020 (2) |

| Depth (cm) | cns (0.1–1.1) | 2019–2020 (2) |

| Length (m) | cns (16.6–19) | 2019–2020 (2) |

*cns = could not sample.

Table 41. Data on core water-quality parameters for New Spring 3 in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location (Width/Depth) |

WY2021 value (Prior values)* |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | Center | cns (1.23) | 2020 (1) |

| Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (5.5) | 2019 (1) |

| pH | 001 | Center | cns (5.58) | 2020 (1) |

| pH | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (5.6) | 2019 (1) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | Center | cns (53.6) | 2020 (1) |

| Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (53) | 2019 (1) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | Center | cns (13.9) | 2020 (1) |

| Temperature (°C) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (17.8) | 2019 (2) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | Center | cns (cns) | none (0) |

| Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (cns) | none (0) |

*cns = could not sample.

Table 42. Water-chemistry data (mg/L) for New Spring 3 in water year 2021, and a range of values from prior years.

| Parameter | Sampling location | Measurement location (Width/Depth) |

WY2021 value (Prior values)* |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkalinity (CaCO3) | 001 | Center | cns (20) | 2020 (1) |

| Alkalinity (CaCO3) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (25) | 2019 (1) |

| Calcium (Ca) | 001 | Center | cns (2) | 2020 (1) |

| Calcium (Ca) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (2) | 2019 (1) |

| Chloride (Cl) | 001 | Center | cns (11) | 2020 (1) |

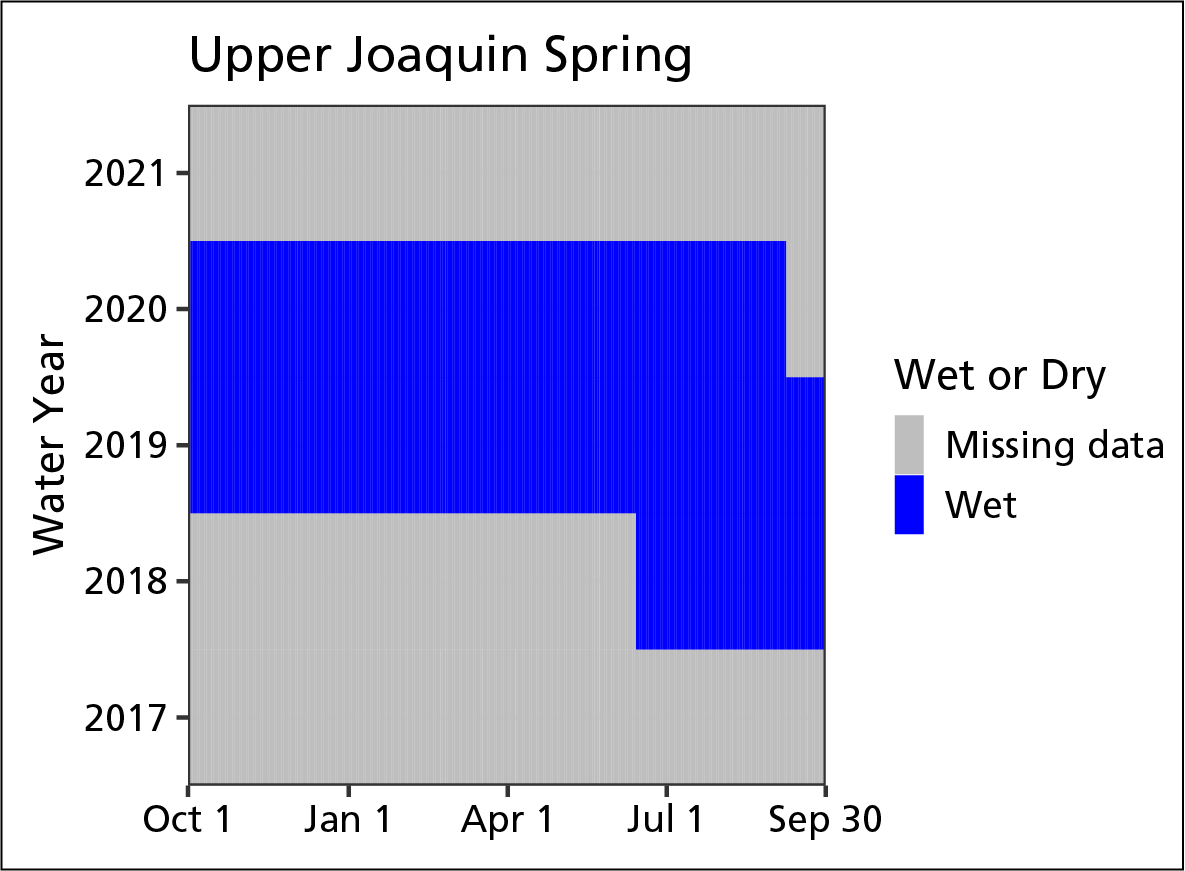

| Chloride (Cl) | 001 | Center/Surface | cns (0) | 2019 (1) |