Last updated: September 20, 2022

Article

Commemorations at Smith Court

The following article was originally published on Smith Court Stories, a digital classroom for teachers and students. Please visit the digital classroom for more articles about the community of Smith Court

Today, the Museum of African American History dedicates itself to sharing “the powerful stories of black families who worshipped, educated their children, debated the issues of the day, produced great art, organized politically and advanced the cause of freedom.”[1] In this way, the Museum preserves the history and memory of the African American community on Beacon Hill. Along with its partner the National Parks of Boston, the Museum follows in the tradition of the sites it stewards, for the African Meeting House and the Abiel Smith School on Smith Court both served as centers for celebrating and commemorating the successes and struggles of Africans and African Americans in Boston.

Emancipation and Independence

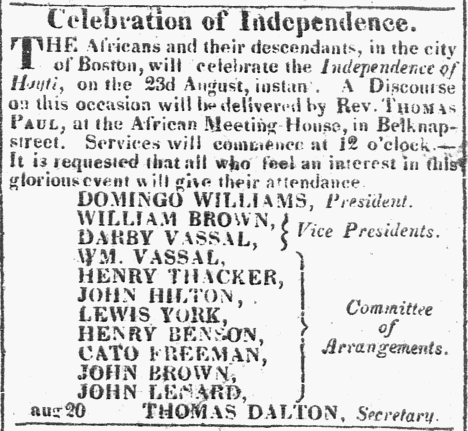

Columbian Centinel

As the Black community in Boston advocated for the abolition of slavery in their own country, they recognized the achievements and gains of others in similar struggles for freedom.

On August 23, 1825, “Africans and their descendants” in Boston gathered at the African Meeting House, also known as the Belknap Street Church, to celebrate France’s recognition of Haiti’s Independence.[2] Reverend Thomas Paul gave a sermon in which he “gave a concise but interesting account of the life of President Boyer [of Haiti]; — and the past and present state of Hayti.”[3] Afterwards, the celebrations continued in the “African School-House, which was beautifully decorated for the occasion.”[4] The individuals who organized the day’s events gave a series of toasts to commemorate the new freedom of Haitians. Darby Vassal, 2nd Vice President for the Day, stated poignantly:

May the freedom of Hayti be a glorious harbinger of the time when the color of a man shall no longer be a pretext for depriving him of his liberty.[5]

An unidentified volunteer directly connected Haiti’s struggle for freedom with that of the enslaved in the United States when he toasted to the

South of the United States – May the Sound of the Independence of Hayti strike home to their hearts as the Gospel does to a Sinner.[6]

Just over a decade later, members of the Black community recognized the “final emancipation of their brethren in the West Indies” at the African Meeting House, known then as the Belknap Street Church.[7] On August 1, 1838, the British Government freed around 800,000 enslaved peoples in the West Indies, which included the islands of “Jamaica, Montserrat, Dominica, Nevis, Barbadoes, St. Vincent, Tortula, St. Christopher, and Demerara.”[8] With the Belknap Street Church almost overflowing with people, this event commemorated the emancipation of the enslaved men and women in the West Indies with a variety of speeches, as well as music performed by the Massachusetts Union Harmonic Society.[9] The Liberator noted,

all felt that the claims of humanity had been regarded, and that the first of August would bring freedom to … moral and accountable beings, who would receive the boon with grateful hearts and exulting voices.[10]

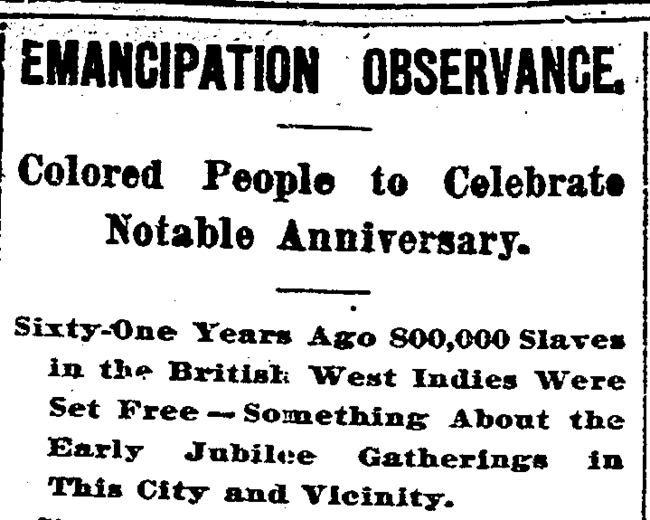

Boston Herald

Black Bostonians continued to recognize this significant date over the years, frequently at the Belknap Street Church (the African Meeting House).[11] The Boston Herald reported on one of the largest of these commemorations that occurred in 1840. This anniversary included “a procession of Sunday school children” who carried flowers as they walked to different schools on Belknap street, as well as evening events held at the Belknap Street Church.[12] The emancipation of the enslaved people in the West Indies resonated with those fighting to end slavery in the United States, as the Boston Herald suggested:

The 1st of August, 1838, is of special interest to the colored people today, because it proved their fitness for freedom and paved a way for the obliteration of slavery in the United States in 1863.[13]

Boston Daily Globe

Fort Wagner Day

To recognize the bravery of the Massachusetts 54th Infantry Regiment, the Robert A. Bell Post, 134, G.A.R. frequently hosted a commemoration for Fort Wagner Day at its headquarters in the Smith School. Fort Wagner Day commemorated the regiment’s charge on Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863 during the Civil War. This day served to remind people of the day’s heroics; for example, during an 1894 gathering veterans who had fought at the battle “met at the hall and retold the story.”[14]

The Bell Post and other veterans’ groups, including the Sergeant William H. Carney Camp, 156, Sons of Veterans, organized events for the day over the years.[15] Usually the program comprised of a combination of instrumental and vocal solos in addition to speeches. Honored guests for the day included veterans of the Massachusetts 54th, such as Major Alexander H. Johnson and Reverend Dr. E. George Biddle.[16] In 1918, Major Johnson “who was the drummer boy of the regiment” performed, using the same drum he carried during the War.[17] At this same commemoration, the Girl Scouts performed a flag drill and Eliza Gardner “gave reminiscences of Civil War days and paid a tribute to Col Robert Gould Shaw.”[18] Reverend Biddle also attended this event and commemorations in other years; sometimes he gave an oration during the program.[19]

Through commemorating the Massachusetts 54th Regiment’s attack on Fort Wagner, the Robert A. Bell Post, 134, G.A.R., and other Black veterans’ groups brought attention to their contributions as members of the Union army in an effort to ensure they would be included in the memory of the Civil War.

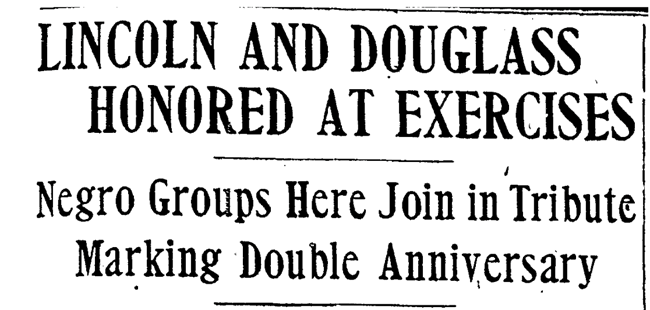

Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln’s Birthdays

Another commemoration held at the Smith School celebrated the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. In 1935, the National Equal Rights League along with a few other groups sponsored the event. An Emergency Relief Act band led by Theodore Bailey “furnished a lively concert of jazz music before the speaking began.”[20] Attorney Albert Wolf spoke about Lincoln and Douglass and

Daily Boston Globe

declared that both are esteemed by posterity not for the heights they reached, but rather for the distance they had to traverse from their humble beginnings to the great fame they finally attained.[21]

The program continued as the Rindge Technical School Glee Club “sang several spirituals and foreign folk-songs” and there was “enthusiastic community singing.”[22]

The African Meeting House and the Abiel Smith School hosted commemorative events significant to Boston’s African American community. Frequently, these commemorations served a larger purpose by connecting the memory of people or events to current issues of the day, as seen through these examples of Emancipation and Independence celebrations, Fort Wagner Day, and Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln’s birthdays.

Footnotes

[1] "About," Museum of African American History, accessed June 2020, https://www.maah.org/about

[2] “Celebration of Independence,” Columbian Centinel, Aug. 20, 1825.

[3] “Celebration of Haytien Independence. Communicated,” Columbian Centinel, Aug. 31, 1825.

[4] “Celebration of Haytien Independence. Communicated.”

[5] “Celebration of Haytien Independence. Communicated.”

[6] “Celebration of Haytien Independence. Communicated.”

[7] “First of August in Boston,” The Liberator, Aug. 10, 1938.

[8] “Emancipation Observance: Colored People to Celebrate Notable Anniversary,” Boston Herald, Aug. 1, 1899.

[9] “First of August in Boston.”

[10] “First of August in Boston.”

[11] “Decade Meeting in Joy Street Church,” The Liberator, Nov. 19, 1858.

[12] “Emancipation Observance: Colored People to Celebrate Notable Anniversary.”

[13] “Emancipation Observance: Colored People to Celebrate Notable Anniversary.”

[14] “Colonel Shaw Remembered,” Boston Globe, July 19 1894.

[15] “Anniversary of Charge on Fort Wagner Observed,” Boston Daily Globe, July 19, 1921.

[16] “Anniversary of Charge on Fort Wagner Observed.”

[17] “Assault on Fort Wagner Anniversary Observed,” Boston Daily Globe, July 19, 1918.

[18] “Assault on Fort Wagner Anniversary Observed.”

[19] “Assault on Fort Wagner Anniversary Observed,”; “Anniversary of Charge on Fort Wagner Observed.”

[20] The Emergency Relief Act funded employment projects that created jobs for people during the Great Depression, and it likely formed Theodore Bailey’s band.; “Lincoln and Douglass Honored at Exercises: Negro Groups Here Join in Tribute Marking Double Anniversary,” Daily Boston Globe, Feb. 15, 1935.

[21] “Lincoln and Douglass Honored at Exercises: Negro Groups Here Join in Tribute Marking Double Anniversary.”

[22] “Lincoln and Douglass Honored at Exercises: Negro Groups Here Join in Tribute Marking Double Anniversary.”