Part of a series of articles titled The History of Slavery in St. Louis.

Article

Slavery and the Law

Missouri Historical Society

"No Law . . . Can Protect Me from the Hands of the Slaveholder!" - William Wells Brown

During Missouri’s first forty years as a state, a series of laws regulated slavery. In 1825, the state legislature passed a law that forced all free Black residents to flee the state if they did not have a certificate allowing them to reside in Missouri. That same year, another law permitted any White resident to apprehend an enslaved freedom seeker and return them to the Justice of the Peace. White residents were given a cash reward for these captures.

Yet another law in 1825 created “slave patrols.” These were composed of White residents who held the right to “visit negro quarters, and other places of suspected of unlawful assemblage of slaves.” If an enslaved person was caught “strolling about . . . without a pass,” the patrols were allowed to administer ten lashes as a punishment.

During the 1830s, a growing abolitionist movement called for the immediate end of slavery. Fearing that this movement would encourage enslaved people to seek freedom, the state legislature passed a law in 1837 banning the “publication, circulation, and [sharing]” of abolitionist literature. Ten years later, the legislature passed a law banning all Black Missourians, whether free or enslaved, from learning how to read and write.

The city of St. Louis passed ordinances that reinforced Missouri laws. Any enslaved person moving about the city had to carry a pass from their enslaver. If an enslaved person was arrested for breaking the law, their enslaver could be fined, and the enslaved person possibly sent to the city’s workhouse.

National Park Service

"Once Free, Always Free"

One unique aspect of the Code Noir was the right of enslaved people to file a lawsuit if they believed they were wrongly enslaved. Missouri continued this practice after it became a U.S. state. Most Southern slave states did not permit enslaved people to file a lawsuit. St. Louis courts heard 287 “freedom suits” from 1810 to 1860. 110 of these cases (38%) successfully led to an enslaved person receiving their freedom by court order. A few cases highlight the nature of freedom suits:

-

One woman, Winny, was enslaved for several years in Illinois, where slavery was outlawed. Winny filed a lawsuit in 1818 in St. Louis. The Missouri Supreme Court heard her case in 1824 and declared her free. The courts embraced the legal precedent of “once free, always free” after Winny’s case.

-

Phillis was a free Black woman originally from Philadelphia. In 1822, a White man named Reddin B. Herring captured her in St. Louis and sold her into slavery in Louisiana. In 1836 she filed a freedom suit in St. Louis. The court declared Phillis free and ordered Herring to pay her $5,000 in lost wages for her many years of enslavement. Phillis’s case was later dismissed after she missed a court date.

-

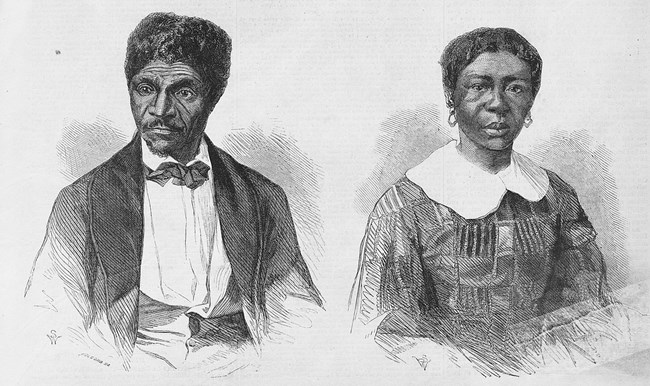

Dred and Harriet Scott were an enslaved couple in St. Louis. Dred’s enslaver, Dr. John Emerson, broke the law by taking the Scotts to Illinois and Wisconsin Territory. Both areas outlawed slavery. Harriet inspired her husband to file a freedom suit in 1846. The Scotts originally won their case, but the Missouri Supreme Court overturned it. In 1857, the U.S. Supreme Court heard the case and famously declared that Dred Scott should not be freed and that all Black Americans, whether free or enslaved, could not be citizens of the United States. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney declared that Black Americans had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” Shortly before the Civil War broke out in April 1861, Congressman John Richard Barret criticized antislavery Northerners for not acknowledging that the Dred Scott case was “the supreme law of the land.” Barret represented St. Louis in the House of Representatives.

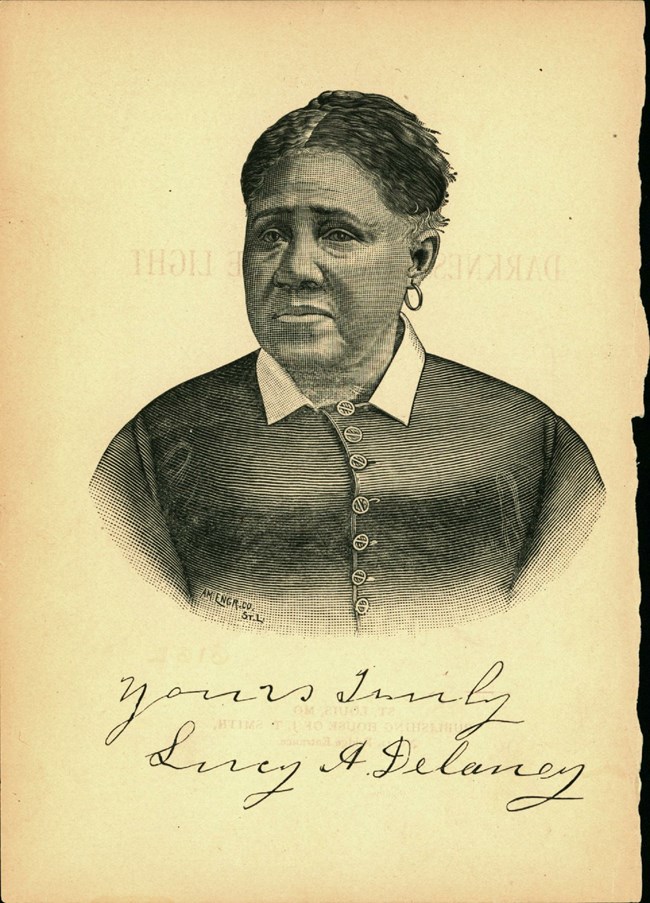

Slavery and Freedom in St. Louis: Lucy Delaney

Lucy Delaney (c.1828-1830–1910) was the only person known to have written a first-person account of a freedom suit. Delaney was born enslaved in St. Louis, but her mother, Polly Wash, had previously been enslaved illegally in Illinois. Wash filed a freedom suit for herself in the early 1840s. After successfully winning it, she filed a freedom suit on behalf of her daughter in 1842. Delaney recalled that while awaiting trial, she was forcibly imprisoned in a dark, cold, smelly jail in the basement of the St. Louis Courthouse (now known as the Old Courthouse) for seventeen months. In the end, Lucy also won her freedom suit.

Delaney’s 1891 book, From Darkness Cometh the Light, recalled her mother’s efforts in their freedom suits. In adulthood, Lucy worked as a seamstress and was married for forty-two years to Zachariah Delaney, with whom she had four children. Delaney also worked with many charities and was an active member of the Women’s Relief Corps, which helped support Union war veterans after the Civil War.

Public Domain

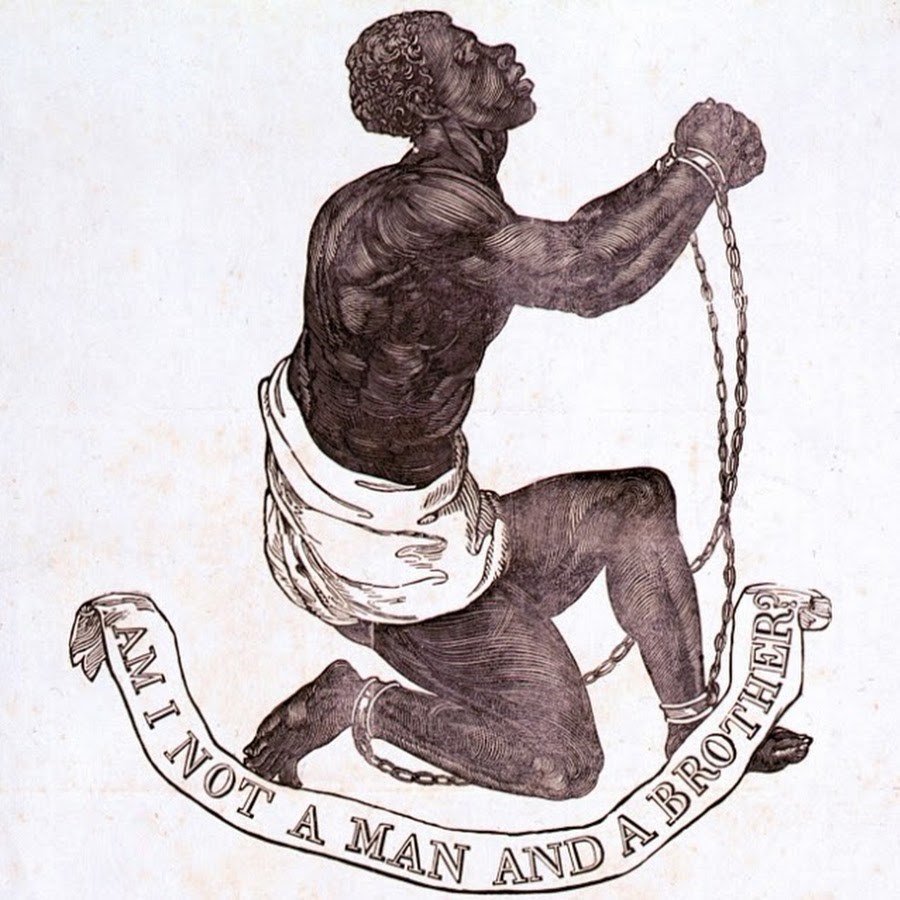

The British Anti-Slavery Society created this medallion in 1795. The society depicted an enslaved man breaking free of his chains and asserting his humanity as "a man and a brother."

Last updated: May 23, 2024