Last updated: December 16, 2024

Article

Shis'g'i Noow, the Tlingit Fortified Village

The Fort Unit site is a story of resistance to Russian colonialism and the fur trade, as well as a story of Kiks.ádi adaptations to a coastal environment and the long history of fishing camps on land they fought to protect. Materials recovered from the site, Russian historical accounts, and Tlingit oral histories, tell a story of traditional use for the land challenged by new forces.

Kiks.ádi Fishing Camps

The Sheet’ká Kwáan (the Tlingit people of the Sitka area), a tribe of the Northern Tlingit, occupied the western half of Baranof Island, the greater portion of Chichagof Island and smaller islands seaward. Cultural traditions established thousands of years ago are still in practice, including the reliance on fish and shellfish for food. Starting over 3,000 years ago, the Sitka Tlingit began using fish weirs to collect salmon, which was and continues to be an important part of their diet. Owing to its significance, the Tlingit traditionally regarded salmon as non-human persons that were handled carefully and commanded respect. Much is known about the location of fishing camps and life from traditional and oral history. Archeological surveys have sought to find physical evidence to corroborate this knowledge.With the onset of summer, the Sitka Kiks.ádi clan and house groups moved from their winter village at Sitka to their fishing camps. The camps sat at various salmon streams throughout Shee Atiká (Sheet’ká), which translates to “Outside Edge” and is the name the Tlingit of the Sitka area call their traditional territory. There they caught and cured salmon and gathered a wide variety of berries and other plants as they became available. Like all Sitka Tlingit, the Kiks.ádi used a wide variety of techniques to harvest salmon in rivers and offshore. These methods included trolling with a hook and line, trapping with basket-style fish traps, and using gaffs, spears, leisters, and stone or wood stake weirs. They stayed in summer encampments until the fall.

When the people returned to the winter villages, they engaged in activities such as harvesting plants, often rosehips (k’incheiyí) and low bush cranberries (daxw), fishing for coho salmon, and drying the fish afterwards. Some went to the mountains to hunt bear, mountain goat, and deer before going to the winter village, because the animals were at their fattest then. The wealth of the summer and fall harvests made winter an ideal season for holding the traditional potlatch.

According to Kiks.ádi oral histories, they inhabited salmon fishing camps along Kaasdahéen (Indian River) within the park since time immemorial (i.e., the earliest human occupation on the island) and through the 1900s. In an interview, Kiks.ádi clan member Isabella Brady recalled her childhood growing up along the Indian River before the park was established: “we had a smokehouse right in the back, a big-sized smokehouse, or a woodshed we called it, and we could dry a lot of fish there.” Three or four smokehouses and adjacent buildings stood on the east bank of the Indian River. It was a very productive salmon fishery between July and November.

Traditional Kiks.adi oral histories recall a series of smokehouses near the perimeter of the Fort Site Clearing. In this survey area, one feature contained a large, flat piece of iron buried about 26 cm deep. A piece of wood with an iron spike was also recovered nearby, so together these artifacts suggest a structure existed at this location. Metal detector inventories identified several use areas and features that point to possible 1800s and 1900s fish smokehouse sites, supporting Hope’s recollection. This study proved that oral traditions, while they may not be written down, are just as accurate and valid as archeological research.

Food Cache Pits

A cache pit is a secure place of storage that keeps contents dry and readily available. Although Tlingit cache pits are commonly associated with winter villages, they were also frequently built for summer fishing camps. The cache pits seen here are resource caches, which often conceal food supplies below living surfaces. When a cache pit is found, that usually means a structure, often a residential one, is nearby.Outside of the Fort Site Clearing, the structural shape and size of Depression A-1 suggests a basement or subfloor cache pit. The glass and ceramic artifacts recovered nearby allude to a historic occupation preceding the Cameron family, who built their fish trap there in the early twentieth century. The Cameron family’s oral history recalls two stone traps from a previous family at the mouth of the Indian River, but the traps eventually washed away. Tlingit occupying the area before the Camerons likely used the cache pit to store food.

Shovel tests in the Fort Site Clearing recovered 306 objects. They included 28 artifacts from Survey Unit B, such as a hand painted teacup shard, a fragment of a transfer-printed saucer rim, a homemade adze made from a pipe, a pontil-marked bottle base, a cut nail, and 22 fragments of a black glass bottle. The dates acquired for these cache pit artifacts provide hard physical evidence that this was the general area of a Kiks.ádi village site dating to the 1900s.

During the winter, the Kiks.ádi constructed large, long term occupation sites with maintained storage facilities. However, cache pits were dug and filled during different seasons in different ways to accommodate the given demands of a season’s associated resource availability. Based on the cache pits that archeologists discovered among salmon fishing camp sites, storage of food procured in the fishing season was probably an important buffer against times of scarcity.

The demands of varied seasons produced the varied archaeological signature we see for these features on the landscape. Highly structured food storage practices created a stable food supply within family groups, as well as an elaborate system of social storage based on ritual inter-tribal exchange events, such as potlatches. Through archeological investigation of these cache pits, we can better understand the ways local communities used food storage to respond to regional social and economic changes.

The Battle of 1804

In June 1741, an Imperial Russian expedition under the command of Vitus Bering entered the Sheet’ká area and explored Sitka Sound. The Spanish followed the Russians, beginning with Hezeta and Bodega in 1775, and then the British when Cook came through in 1778. American traders followed shortly after in 1785, and the French headed by La Perouse passed through a year later. By 1790, a lively and competitive international trade had begun to develop in Tlingit territory. The Kiks.ádi were introduced to firearms, blankets, and other commodities in exchange for furs.

Eager to monopolize the fur trade, the Russians formed the Russian American Company in 1799. That year, the people of the Kiks.ádi village, Shee Atik’á, hosted Aleksandr Baranov, who represented the interests of the newly formed Russian-American Company. However, Baranov was not highly regarded and the Kiks.ádi found him to be cold, aggressive, and stingy. His harsh ways earned him the pejorative title of L'ush Teix', which translates to "Without a Heart".

The Kiks.ádi clan initially maintained good relations with the Russians, but Baranov was determined to establish a fur trade enterprise on the island – no matter what – and secured a location for a new trading post through a series of conflicts and threats. Inevitably, this situation rapidly deteriorated to a point of violence, when on June 15, 1802, Kiks.ádi warriors destroyed the Archangel Saint Michael’s Redoubt at Old Sitka. Led by K’alyáan of the At Uwaxiji Hit, the Kiks.ádi burned the fort to the ground, killing many inhabitants and capturing others. However, this was not an isolated event, as the Russians had spawned widespread resentment and hostility by their behavior and experienced almost simultaneous attacks at this time across a broad area, from rebellions in Yakutat in the north to the Kaigani Haida in the south.

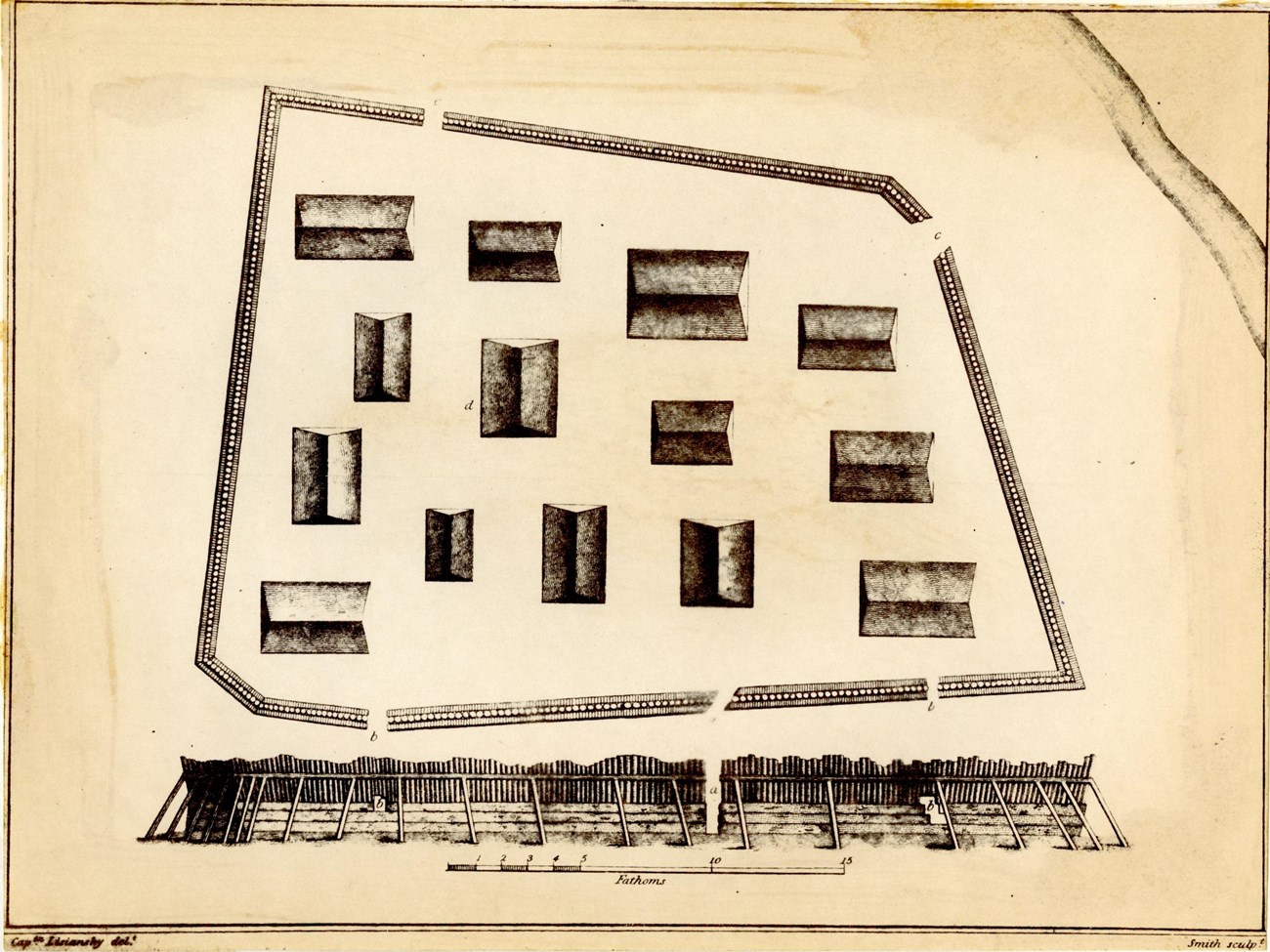

This unusual character of Shis'g'i Noow reflected the Tlingit’s complete familiarity with their Russian adversary’s weaponry. It was built specifically for the coming confrontation with the Russians and reflected the Russian fur trade expansion to the shores of North America. Baranov underestimated Kiks.ádi resolve to control their own trade and lands. With their acquisition of firearms from the American and British traders, the Kiks.ádi became increasingly bold and ready to take on Baranov’s forces of 120 Russian-American Company employees and 800 Aleut allies. They finally converged on Sitka in September 1804 to bring the Tlingit, but more specifically the Kiks.ádi clan, under the dominion of Imperial Russia.

Two large pits, Depressions A-2 and A-3 lie in the heart of the battle zone as indicated through recovered musket and cannon balls. Two cannon balls and two canister shot, both from 12-pound cannon, and four musket balls were recovered near the center of the two depressions. The depressions are similar in size, orientation, and have uniform berms on the north side of each, confirming they are man-made.

While it is likely these depressions represent cache pits built underneath fish smokehouses sometime after the battle, they may also be associated with Shis'g'i Noow. The fortified village was located within the Fort Clearing, and oral histories reference pits in which the Kiks.ádi took refuge from Russian cannon and musket fire. Multiple Russian accounts described dugout pits inside each house and defenses that included dugout houses set in a shallow depression in the ground.

Baranov destroyed Shis'g'i Noow, possibly by burning, but perhaps more likely by salvaging the wood for construction of his new trading post on Castle Hill. With Kiks.ádi withdrawal and subsequent Survival March over the rugged mountains to the other side of the island, the Russians built a fortified compound, naming it Novo-Arkhangelsk. Although the Tlingit Kiks.ádi had lived in this area for centuries and participated in an intricate tapestry of interrelationships with the land, surrounding waterways, animals, and plants, and other peoples, the Russian-American Company seized much of the Tlingit land by force, with no compensation to the Tlingit.

Sitka National Park originated as a National Monument specifically to commemorate the traditional village of the Kiks.ádi clan and the site of the 1804 Battle of Sitka, making Shis'g'i Noow central to interpretation at the park and a significant focus for learning more about Tlingit history and culture. Today, the site retains its integrity and contains data that will likely yield more important historic information in the future.

Sources

Howey, Meghan C. L., and Kathryn E. Parker

2008 "Camp, Cache, Stay Awhile: Preliminary Considerations of the Social and Economic Processes of Cache Pits along Douglas Lake, Michigan." Michigan Archaeologist, vol. 54, no. 1, pp. 19-44.

Hunt, William J., Jr.

2010 Sitka National Historical Park. The Archeology of the Fort Unit: Results of the 2005-2008 Parkwide Inventory; Survey, Testing, and Analytical Data. Vol. 1 and 2. Midwest Archeological Center. National Park Service.

Thornton, Thomas F., and Fred Hope

1998 Traditional Tlingit Use of Sitka National Historical Park. National Park Service.

Tags

- sitka national historical park

- archeology

- archaeology

- native alaskan

- russian

- alaska

- alaska native

- alaska native history

- tlingit

- indigenous heritage

- traditional ecological knowledge

- food history

- agricultural history

- economic history

- military history

- colonial history

- russia

- engaging with the environment

- native foods

- traditional knowledge