Last updated: October 7, 2021

Article

Sensor This! EMUs VS Bears and a Microclimate for Destruction!

Jordan Starks

Why does this awkward, yet funny occurrence matter to the story of microclimate research in the park? Because it’s just the most recent wrinkle in the larger crazy journey behind graduate student researcher Jordan Stark’s microclimate project. The recipe is simple, add one-part black bear, one-part microclimate, one-part environmental micro-controller units or (EMUs) sensors, and a dash of Covid-19 and you have a recipe for a beautiful scientific disaster. And it all starts with dinosaurs.

Jordan did not always want to change the world through environmental studies or biology, she wanted to be a paleontologist. “I was fascinated by dinosaurs when I was a child!” Jordan exclaimed over the phone. She did tell me that fascination led her to opportunities in high-school science outreach, prairie restoration in Washington State, helping with research for a year in Puerto Rico, and now visiting the Great Smoky Mountains National Park to perform microclimate research for a collaborative research project between Duke and Syracuse University.

Two years ago, Jordan became part of Syracuse’s team that would study microclimate - the climate under the canopy of trees - while Duke University led the effort in studying the climate above the Smokies canopy. “We know that under the canopy the climate can change within a 10-meter scale. According to the sun, shade, and what side of the slope or mountain you are located, we have a good model of how the temperature varies throughout the park.”

Jordan Stark

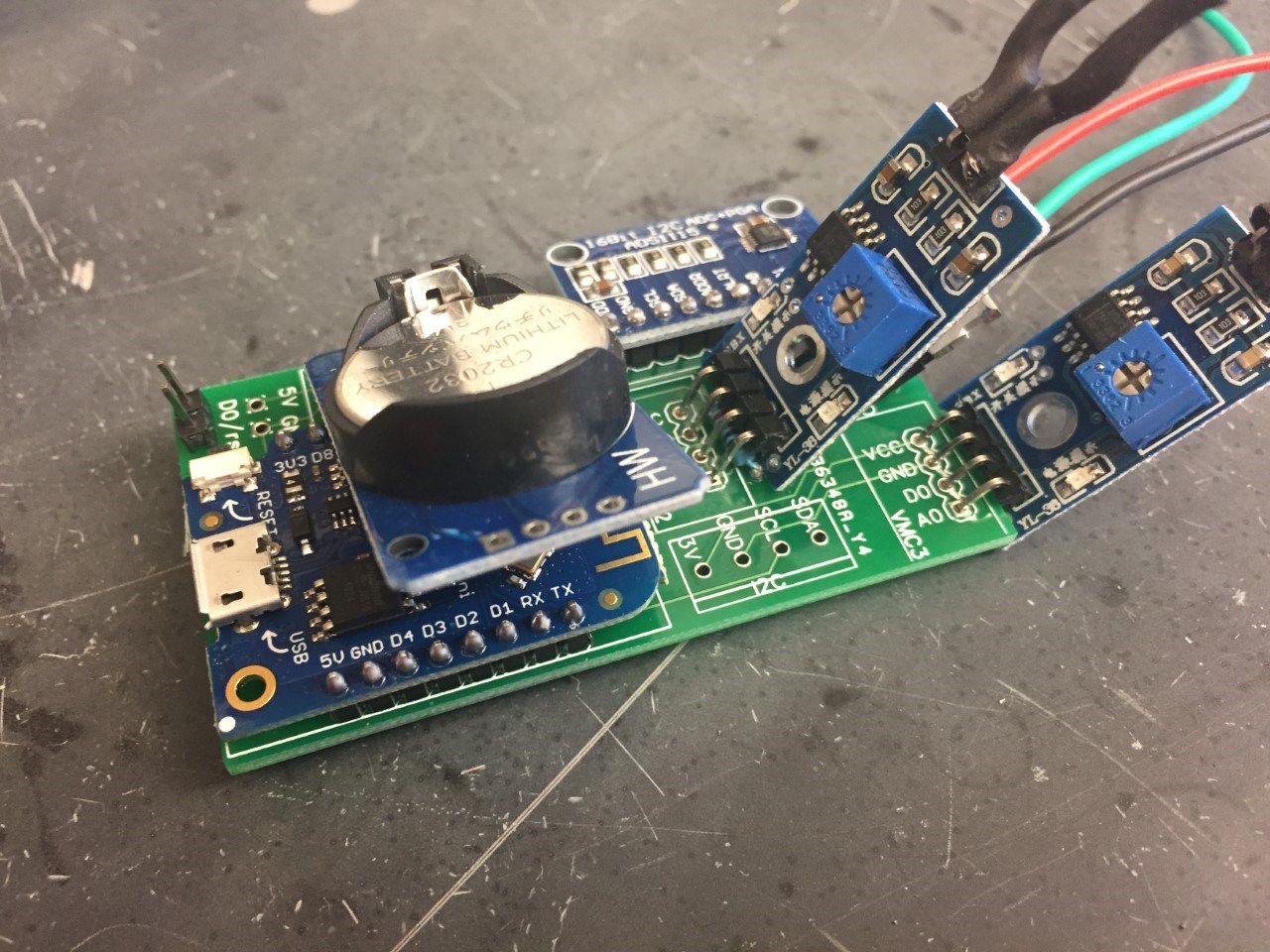

No, Jordan did not go into the business of environmental science to code, but this research depends on programing the sensors, which will register the temperature and soil moisture throughout the park. She uses Arduino code, which turns EMUs into tiny computers that take measurements every hour and then automatically shut-off until the next reading, so that the AAA batteries can power a sensor for a whole year. What Jordan did not suspect is that her research would be the start of a unique relationship between EMUs and black bears.

Jordan Stark

The next morning, she and her research assistant took in the sweet balsam air and yellowish hues of mountain sun and started their field work. They grabbed their 30-pound backpacks of rebar, EMUs, and hammers for meandering along trails such as the Cataloochee Divide, Purchase Knob, Mount Sterling, and eastern end of the Appalachian trail. They installed rebar and sensors in some of the highest peaks and the lowest lowlands of the park. How do they choose these sites you ask? The criteria are simple. First, they need a variety of sites with different elevations and percentage of canopy cover, so the EMUs can measure light levels in each area. Next, they need locations that have enough soil to place the EMUs, previously approved by the park. Miles of hiking and 38 EMUs later, Jordan left the Smokies feeling optimistic about her research.

As Jordan anticipated what these small EMUs would tell her, she received an email from Great Smoky Mountains Science Coordinator, Paul Super. The email featured photos of a horrid scene of destroyed sensors. Thanks to the resident bears of the Smokies. Jordan’s heart dropped to the pit of her stomach and she wondered what would happen to her research. When Jordan returned to the Smokies, she used previously programmed GPS coordinates to find the thirty-eight EMUs - twenty-eight of which were destroyed by bears and hogs. You can imagine each bear telling their friends that there was a new chew toy to play with and they should get them, while the getting was good. The few sensors that survived the melee of bear play were found in pools of water or were pretty torn up.

What would these sensors tell Jordan? One of the challenges that come from these EMUs is the amount of data that it records. Hundreds, if not thousands of hours of data can be recorded in several months, leaving Jordan to slowly sort through the data of each EMU. Although Jordan is still analyzing, she hopes that her team will be able to put numbers on exactly how much, smaller topographic features play into the variation, so that we can make predictions about places and times where we don’t have sensors. Future survey sites are useless if curious bears enjoy the science as much as the researchers, though. So, Jordan pondered on ways that she could deter these bears from chewing the EMUs to oblivion.

What would these sensors tell Jordan? One of the challenges that come from these EMUs is the amount of data that it records. Hundreds, if not thousands of hours of data can be recorded in several months, leaving Jordan to slowly sort through the data of each EMU. Although Jordan is still analyzing, she hopes that her team will be able to put numbers on exactly how much, smaller topographic features play into the variation, so that we can make predictions about places and times where we don’t have sensors. Future survey sites are useless if curious bears enjoy the science as much as the researchers, though. So, Jordan pondered on ways that she could deter these bears from chewing the EMUs to oblivion.

She joked with her colleagues about creating EMUs that could make sounds or dispense sprays but no matter what she came up with, she always understood that she was placing enjoyable little plastic objects in the homes of bears. After all, how can anyone be mad at a creature that rolls down hills, eats blackberries, and has been in the Smokies long before her research? “It was frustrating but in ecology, there are so many elements that are not in our control, Jordan said while laughing. This is how EMU 2.0 was created. EMU 2.0 measures soil moisture from surface to several centimeters underground and soil temperature. EMU 2.0 was equipped to elude those curious bears.

In October of 2019, Jordan re-visited the park with new sensors in-hand. She traveled through the Smokies with logging tape, marking trees for visuals, and creating GPS points for future reference. Learning her lesson from the first visit, she returned to the park in late March of 2020 to check on the EMUs’ batteries and assess how they re-designed sensors were faring against the bears. It seemed like everything was going her way. She had enough previous data to know where to place the EMUs, she had 23 new EMUs that the bears would not destroy, and she would have additional data for her research by the end of the summer. What could go wrong?

In October of 2019, Jordan re-visited the park with new sensors in-hand. She traveled through the Smokies with logging tape, marking trees for visuals, and creating GPS points for future reference. Learning her lesson from the first visit, she returned to the park in late March of 2020 to check on the EMUs’ batteries and assess how they re-designed sensors were faring against the bears. It seemed like everything was going her way. She had enough previous data to know where to place the EMUs, she had 23 new EMUs that the bears would not destroy, and she would have additional data for her research by the end of the summer. What could go wrong?

As Jordan was gearing up to make her 5th trip to the Smokies, the Covid-19 virus ran ramped throughout the world. Businesses, schools, and parks began to close down in response to Covid-19 and so did her research. “Depending on the week, I did not know when I would return to the park to continue my research.” Hearing Jordan’s discomfort shows the passion for learning more about microclimate and the endeavors that she dealt with to pursue that passion. After some discussion between the park and Syracuse University, finally Jordan was able to return to the Smokies in late June of 2020.

GPS and metal detector in-hand, she was determined to place 75 new sensors in Big Creek, Cosby, Mount Sterling, Purchase Knob, and the 441 Corridor trails. Jordan was used to not hearing visitors deep in the mountains, but due to Covid-19, this trip was much different. The campgrounds that were usually crowded with people and chatter were closed but many park visitors took to the trails just like Jordan. Besides the hikers on the trails, Covid-19 closures made the silence deafening during her hikes. Jordan doesn’t listen to music while hiking, she doesn’t have an assistant to chat with, but she does have the constant reminder that she is alone with her research. Some days the only thing she may hear are the loud sounds she makes to ensure that the bears know she’s coming. Other days her mind is wrestling with her research. She usually snaps back to reality when the weather drastically changes, but even if inclement weather hits, Jordan enjoys her fieldwork in the park. Rain or shine, wondering or wandering, Jordan ensured that the EMUs were placed in the Smokies.

Through bears, inclement weather, and Covid-19 Jordan, has had several setbacks, but not to her spirit towards microclimate research and how it can help the park. “The research is interesting because there are parts of it that are theoretical and there are things that have direct benefits...I hope this informs fire risk and help salamanders because those little guys are living in the soil. My other work, which is trying to create models and maps based on small changes in the environmental conditions to indicate the species that are most at risk of climate change is important, as well.”

Although many people pass by her on the trails without words, the bears hunt her EMUs down like they’re prey in a documentary, and Covid-19 has caused delays, her research is helping us understand the distinct communities of flora that grow in particular climates of the park. These are communities of flora that many overlook but play a vital part in the park. After all the adversity that Jordan faced, while conducting her research in the park, I had to ask her one last question, “when you think about the Smokies, what intangible feelings do you have?” “I can never get over the beauty of the Smokies.” “In a single day, you can hike in a place that feels tropical and into a [chilly] spruce forest habitat.” “I also wonder if the bears are watching me when I do my research. I doubt I will ever catch a bear destroying a sensor; bears are too sneaky, but the bear problem has become a running joke in the biology department. We call it EMUs vs bears.” Jordan lightheartedly stated before ending the call.

GPS and metal detector in-hand, she was determined to place 75 new sensors in Big Creek, Cosby, Mount Sterling, Purchase Knob, and the 441 Corridor trails. Jordan was used to not hearing visitors deep in the mountains, but due to Covid-19, this trip was much different. The campgrounds that were usually crowded with people and chatter were closed but many park visitors took to the trails just like Jordan. Besides the hikers on the trails, Covid-19 closures made the silence deafening during her hikes. Jordan doesn’t listen to music while hiking, she doesn’t have an assistant to chat with, but she does have the constant reminder that she is alone with her research. Some days the only thing she may hear are the loud sounds she makes to ensure that the bears know she’s coming. Other days her mind is wrestling with her research. She usually snaps back to reality when the weather drastically changes, but even if inclement weather hits, Jordan enjoys her fieldwork in the park. Rain or shine, wondering or wandering, Jordan ensured that the EMUs were placed in the Smokies.

Through bears, inclement weather, and Covid-19 Jordan, has had several setbacks, but not to her spirit towards microclimate research and how it can help the park. “The research is interesting because there are parts of it that are theoretical and there are things that have direct benefits...I hope this informs fire risk and help salamanders because those little guys are living in the soil. My other work, which is trying to create models and maps based on small changes in the environmental conditions to indicate the species that are most at risk of climate change is important, as well.”

Although many people pass by her on the trails without words, the bears hunt her EMUs down like they’re prey in a documentary, and Covid-19 has caused delays, her research is helping us understand the distinct communities of flora that grow in particular climates of the park. These are communities of flora that many overlook but play a vital part in the park. After all the adversity that Jordan faced, while conducting her research in the park, I had to ask her one last question, “when you think about the Smokies, what intangible feelings do you have?” “I can never get over the beauty of the Smokies.” “In a single day, you can hike in a place that feels tropical and into a [chilly] spruce forest habitat.” “I also wonder if the bears are watching me when I do my research. I doubt I will ever catch a bear destroying a sensor; bears are too sneaky, but the bear problem has become a running joke in the biology department. We call it EMUs vs bears.” Jordan lightheartedly stated before ending the call.