Last updated: October 5, 2022

Article

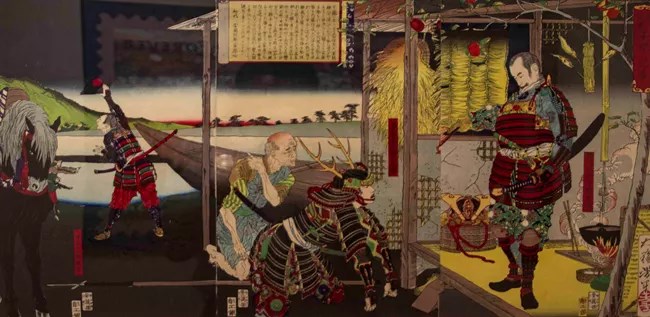

CHAPTER 1: Sengoku Jidai: Japan's Warring States Period

Gifu Sekigahara Battlefield Memorial Museum Image

The American Civil War stands as a dividing line in American history which began the first steps of creating the United States as it exists today: an economic and military powerhouse with highly ingrained principles about the nature of freedom and equality. It also fits into a relatively small period of human history.

Although it came as the result of decades of mounting tensions over the expansion of slavery, including the violence of Bleeding Kansas and John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, the Civil War was only about four years long.

And while there was certainly a fair share of intrigue, shifting loyalties, and messy ambiguities among the people who participated in the Civil War, there were two clear parties in the conflict: the federal government of the United States of America, who wished to maintain a single united country, and the Confederate States of America, who wished to break away from the U.S. to create a new nation.

In Japan, though, “civil war” means something totally different. Throughout its long history, Japan has experienced many periods of warfare between rival factions vying for control of the whole country, but the most famous was the Sengoku (warring states) Period that lasted from the middle of the 15th Century to the start of the 17th Century.

The emperor had long been a mere figurehead in Japanese politics, with the true power residing in the figure of the shogun. But after the start of a succession crisis in 1467, the Ashikaga Shogunate, too, lost its real power, shattering Japan into dozens of provinces led by rival lords called daimyo, all vying for influence in a massive free-for-all for control Japan.

Gifu Sekigahara Battlefield Memorial Museum Image

Over the decades, alliances shifted among the daimyo, and without a true centralized authority, Japan remained a splintered, chaotic place. However, three powerful generals came to the forefront in the latter half of the 16th Century: Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu.

After a stunning victory over a rival at the Battle of Okehazama in 1560, Nobunaga set out asserting his influence in South Central Honshu, the main island of Japan. Alongside his loyal generals Hideyoshi and Ieyasu, he came close to unifying Japan under one banner for the first time in over a century.

After Nobunaga was betrayed by another general and assassinated in 1582, Hideyoshi managed to outmaneuver Ieyasu to become his former master’s successor, and he essentially completed Japan’s unification with himself as de facto ruler. In addition to his enduring internal reforms, he waged a disastrous war in Korea in the hopes of keeping the nation of war-primed samurai occupied during the 1590s.

When Hideyoshi died in 1598, his sole heir was his son Hideyori, a mere boy of 5. Hideyoshi left a council of five regents to look after affairs until the young Hideyori came of age. However, Tokugawa Ieyasu, who was the most powerful and wealthy of the regents, was not keen to wait around for the child to claim the power he felt a warrior like himself deserved after decades of loyal and effective service.

There was almost immediately a split among the various daimyo and regents: those who backed Tokugawa Ieyasu, and those loyal to the Toyotomi clan and the young Hideyori. Ishida Mitsunari, one of the late Hideyoshi’s closest friends, came to the forefront of the anti-Tokugawa faction, and after luring Tokugawa Ieyasu out of Osaka and to the East, he mobilized an army of pro-Toyotomi samurai to defeat him in battle.

On October 21, 1600, Ishida Mitsunari’s “Western Army” and Tokugawa Ieyasu’s “Eastern Army” finally clashed at a strategically vital crossroads near the town of Sekigahara some 60 miles east of Kyoto. Considering Mitsunari an illegitimate commander unworthy of their support, several generals, most famously Kobayakawa Hideaki, defected from the Western Army and turned their weapons against Mitsunari himself. With the Eastern forces bearing down on him, and the betrayal of his generals, Mitsunari did not stand a chance. He was later captured and executed. The last great obstacle in the way of Tokugawa Ieyasu was gone.

Over the next few years, there were other battles against the remnants of Toyotomi loyalists, but after his massive victory at Sekigahara, Ieyasu had shown any other potential rivals that resistance was futile. The emperor soon gave Ieyasu the symbolic title of shogun, and for more than 250 years, the Tokugawa Shogunate would rule over a united and relatively peaceful Japan. The Sengoku Period was finally over.