Last updated: July 20, 2021

Article

Seip Earthworks to be Nominated to the World Heritage List

Bret J. Ruby, PhD

Park Archeologist and Chief of Resource Management at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park

A version of this article was published in the Newark Advocate on May 5, 2021.

Park Archeologist and Chief of Resource Management at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park

A version of this article was published in the Newark Advocate on May 5, 2021.

1848, Squier and Davis

There are only 24 World Heritage Sites in the United States, and just over 1000 in the world. The international community recognizes these as places of such outstanding universal value that all of humanity has a stake in their preservation. The United States was the first nation to propose the idea of an international treaty to protect globally significant natural and cultural heritage sites. This idea came to life in 1972 when the United States was the first nation to ratify the World Heritage Convention. This was the 100th anniversary of Yellowstone becoming the world’s first national park. This was no coincidence: the World Heritage List was designed as an international version of America’s national park idea.

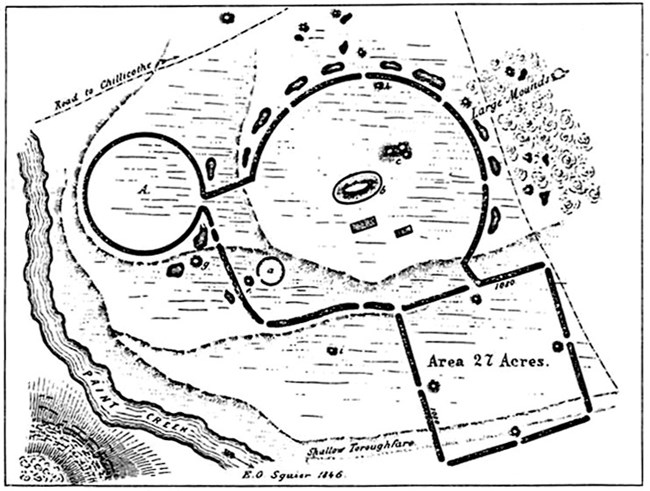

The Seip Earthworks deserves a place among the wonders of the world because it is a masterpiece of human creative genius. American Indians designed and built the complex nearly 2000 years ago, and its form and size shows their sophisticated knowledge of geometry and astronomy. They built almost 2-1/2 miles of earthen embankments to form three geometric figures: a large circle enclosing 40 acres; a smaller circle enclosing about 18 acres; and a precise square enclosing 27 acres. Remarkably, the builders constructed four more of these “tri-partite” enclosure complexes within 20 miles of the Seip Earthworks, each using circles and squares of the same dimensions. The Indigenous peoples’ knowledge of astronomical cycles is shown in the alignment of the square enclosure: the diagonal of the square points to the rising sun on the winter solstice. Two gigantic earthen mounds were built near the center of the complex. The biggest is a loaf-shaped mound more than 240 feet long, 160 feet wide, and more than 30 feet tall. At ten cubic yards of earth per load, it would take almost 2000 dump truck loads to build just this one mound!

What could have motivated Native Americans to invest so much knowledge, labor, and care in this masterpiece of landscape architecture? Clues are found under the huge mounds. Enormous multi-roomed, timber-framed buildings once stood here. These buildings sheltered tombs where the honored dead were laid to rest, as well as shrines, altars, and special spaces where ceremonial regalia and religious equipment was decommissioned and deposited. Skillfully crafted objects made of materials from faraway places such as copper, marine shell, obsidian, and mica suggest these great religious centers were known to Native nations all across eastern North America.

A recent partnership between the National Park Service and the German Archaeological Institute resulted in a high-resolution magnetic scan of the entire site. Today we’re using the magnetic map as a guide to mow an accurate pattern in the grass to highlight the earthworks. Visitors are welcome to respectfully wander through these vast sacred spaces and marvel at these masterworks of Indigenous design. Plan your visit at www.nps.gov/hocu

Photo credit: Timothy E. Black