Last updated: December 4, 2020

Article

Scientists Analyze Feathers to Understand the Origins of Sharp-shinned Hawks Migrating Over the Bay Area and Beyond

Jessica Weinberg McClosky / Parks Conservancy

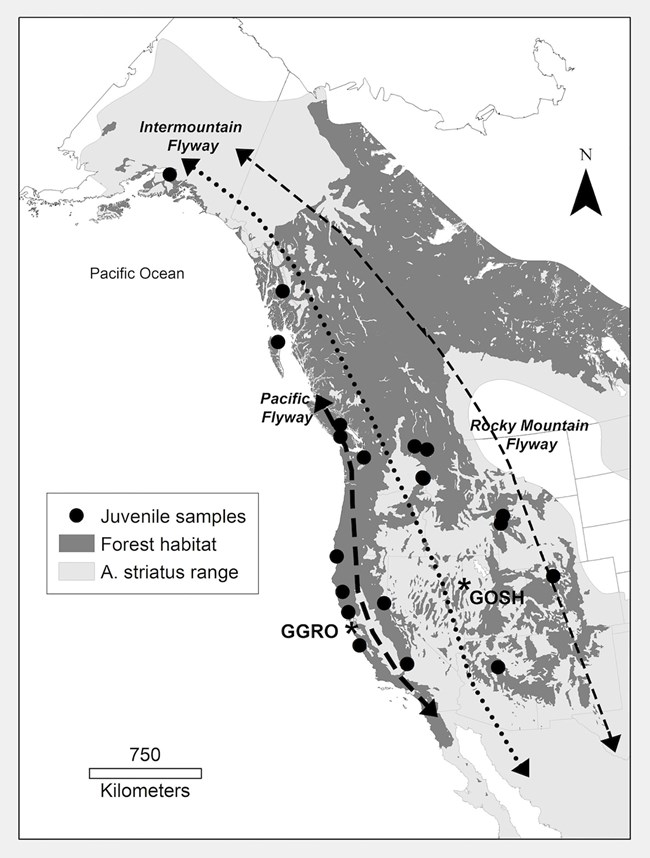

November 2020 - North America’s smallest hawks are cryptic creatures. Sharp-shinned hawks, or “sharpies” in birder-speak, breed in dense northern or high-elevation forests where they are difficult to find and track. Some overwinter in the US, while others migrate all the way to southern Central America. When they’re heading south along popular raptor migration routes, or flyways, is when they’re easiest to spot. But their large-scale movement patterns are also poorly understood. Recently, a team of scientists, with institutions including the Golden Gate Raptor Observatory (GGRO), used feather samples to test a theory about sharpie migratory movements in the western US.

Wommack EA, Marrack LC, Mambelli S, Hull JM, Dawson TE. 2020. Using oxygen and hydrogen stable isotopes to track the migratory movement of Sharp-shinned Hawks (Accipiter striatus) along Western Flyways of North America. PLOS ONE 15(11): e0226318.

The scientists hypothesized that juvenile sharpies would use different flyways in the fall based on where they hatched in the spring. For example, perhaps birds hatched west of the Sierras consistently migrate via the Pacific Flyway while those to the east use a different route. They put this theory to the test using hydrogen and oxygen stable isotope analysis of feather samples. Some samples came from birds captured during GGRO banding operations in the Marin Headlands along the Pacific Flyway. Others came from a banding station along the Intermountain Flyway. The team compared these against a model based on samples from museum specimens with known origins.

How water evaporates and condenses creates regionally distinct hydrogen and oxygen isotopes. When animals drink from water sources tied to precipitation, those stable isotopes make it into the food chain, and ultimately into bird feathers. From analyzing these isotopes, the scientists discovered that their hypothesis was incorrect. They found that, in fact, sharpies migrating east or west of the Sierras may come from overlapping breeding territories. Still, they did see some differences. Pacific Flyway migrants came from a broader area stretching from the coast to beyond the Rocky Mountains. Intermountain Flyway migrants, on the other hand, appeared to originate from a narrower area east of the Sierras. These, and other novel findings about the utility of analyzing hydrogen vs. oxygen stable isotopes, are publicly available in their newly published article in PLOS ONE.

Understanding where sharp-shinned hawk populations spend different parts of their lives is an important step towards knowing how to protect them. The authors note that interpreting stable isotope analyses can be tricky and imprecise, so more studies and larger sample sizes could provide even more useful information in the future.

For more information

- Wommack EA, Marrack LC, Mambelli S, Hull JM, Dawson TE. 2020. Using oxygen and hydrogen stable isotopes to track the migratory movement of Sharp-shinned Hawks (Accipiter striatus) along Western Flyways of North America. PLOS ONE 15(11): e0226318.

- Golden Gate Raptor Observatory Research Overview