Last updated: January 27, 2022

Article

Scientist Profile: Dr. Jena Hickey, San Francisco Bay Area Inventory & Monitoring Network Program Manager

On getting into biology…

“I would say I was born a biologist, to be honest. Since I was a toddler, I was already out playing in the mud, and inquisitive about plants and animals and insects. I saw things like Discovery Channel or National Geographic, and that was my play—to pretend I was a naturalist in the forest.”

“By the time I was at the university level, I had a strong desire to help with environmental issues because it seemed like there were a lot of environmental crises when I was in high school. I remember when the Exxon Valdez oil spill happened, and that there were scientists and conservation workers cleaning oil off of all different kinds of species. Those environmental crises really struck a chord with me. I wanted to be part of understanding, ‘How do humans impact nature? And how can we do a better job of taking care of this planet that takes care of us?’”

On science…

“I just love the scientific process, starting off with observation, and then asking questions. Really, it's a very creative thinking process. There's something satisfying about coming up with a valid study design that will eventually answer an ecological question. Like, ‘Why does this animal use this habitat and not this other habitat?’”

“I talk about science all the time because I love it. And it's all around us, right? Like why is it important to sleep? And did you know that even sharks and dolphins sleep? Science comes up in a lot of conversations, and I probably should avoid sounding like an expert on these topics because I’m not. They simply interest me. I'm constantly intrigued by what other scientists are discovering.”

On her professional journey…

“I came to the National Park Service by a very circuitous path. I started off on the straight and narrow. I earned a bachelor's degree in biology and a master's degree in zoology and physiology. Then I did a series of jobs with state and federal agencies. I worked for Idaho Fish & Game investigating the causes of juvenile mortality in sage grouse. Then I worked with the US Bureau of Reclamation, managing the wetlands and threatened-and-endangered species programs and diving for endangered mollusks to monitor their populations in the Snake River. After that, I moved on to the Forest Service.”

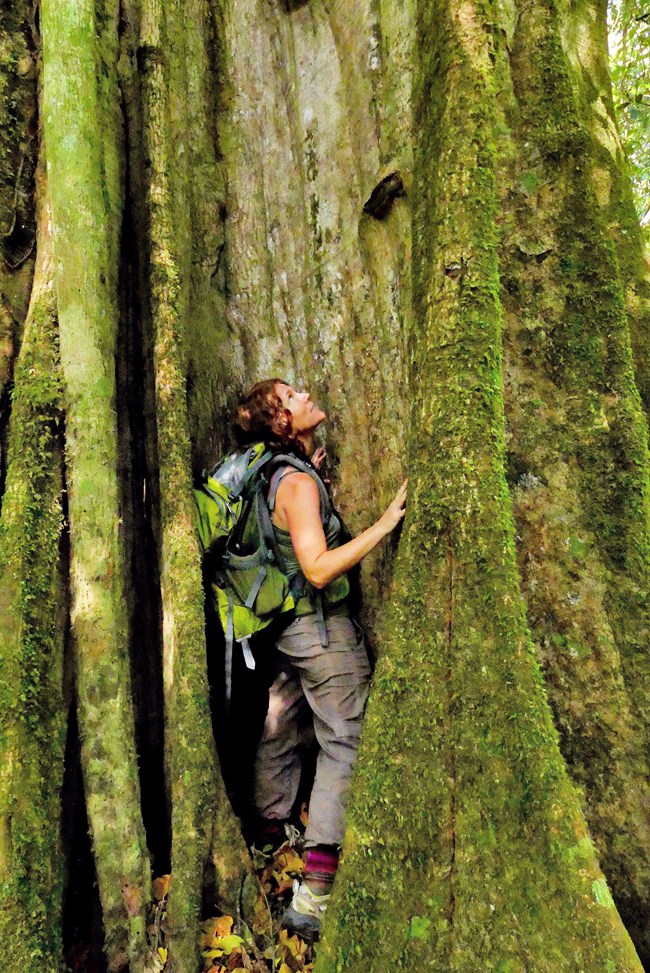

“Not many people realize that almost all federal agencies have an international component. Once I learned that the Forest Service had people like me—wildlife biologists—helping with natural resource management in Tanzania and other faraway places, I followed every lead for an opportunity to work in Africa. Eventually, I managed to get selected for a mission to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The purpose was to engage in conversations about sustainable hunting and landscape planning with lots of local people living throughout a massive area that was also inhabited by bonobos and forest elephants. It was a fantastic and life changing experience. The location was extremely remote—in the middle of the rainforest—deep in the heart of the Congo Basin. We needed bush planes and dugout canoes and outboard motors and motorized dirt bikes to get around.”

“That was a major milestone because I pivoted. I quit my Forest Service job, started a PhD studying bonobos, and ended up leading an expedition for six months to gather the data for my dissertation. After I graduated, I did a couple postdocs, and then the opportunity to work with mountain gorillas fell in my lap. It was the kind of job I couldn't possibly decline because it involved monitoring mountain gorilla populations and working in all three countries where they exist—Rwanda, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. And I've always wanted to work at the nexus of conservation and scientific research. So I went for it.”

“I stayed for five years, which gave me time to help survey the entire global population of mountain gorillas. There are two populations of mountain gorillas left in the world. One, the southern population, is in an area called the Virunga Massif, located at the border where Rwanda, Uganda, and DRC all come together. The first two years essentially involved monitoring and estimating the abundance of that southern population.”

© Jena Hickey

“But then there's a second population up north in the Bwindi-Sarambwe ecosystem which also needed to be surveyed. So I stayed long enough to survey the global population of mountain gorillas with a whole new technique that helps account for the fact that they are social—that they live in groups. Before, mountain gorilla populations had been estimated using capture-mark-recapture techniques that assume all individuals are found independently. In fact, social species are found in groups. If we don’t find the group, we don’t find any of the individuals. And one can expect that larger groups are more likely to be found than smaller groups. So, we developed a modified approach to capture-mark-recapture where we first calculated the probability of detecting the group, and then once the group was found, we then calculated the probability of detecting the individual in the group.”

On a persistent challenge...

“A theme throughout my career has been to really work through and refine communication skills; to try hard to listen and hear what somebody is saying. That most strongly started in Congo during my PhD fieldwork. Communication is always tricky. And then the cultural differences made it even harder—different mannerisms, different expectations, different concepts of gender roles. I was often the only woman, period. And then to be the leader at the same time could be pretty challenging. Not just for me, but it was clearly challenging for some of the team members to have a female supervisor. So we worked through those things and usually it worked out okay. We seemed to gain an enhanced understanding of each other's perspectives once we talked it out.”

On her work now…

“And then it was time to come home to California, which is where I was born, and apply for the jobs that I wanted back when I was at the Forest Service. Those were inventory and monitoring jobs because, to me, long-term data sets are really cool, as is working on scientific questions that are applied—that end up being meaningful to land managers.”

“So here I am. I'm still learning a ton every day. The responsibilities are a combination of science and administration, but the heart and soul of it is, of course, the science. We can't monitor all natural resources, but the National Park Service has vital signs which are our way of having our finger on the pulse of our ecosystems. The idea is to learn, ‘How are we doing in terms of managing the lands and the resources that are entrusted to us? And then if there's something that is not doing well, why is that? Is this something that's happening nationwide or globally, or only in our jurisdiction? Is there something we can do to mitigate that?’”

“The state of nature, and whether or not it's in good shape—it's not a given. And frankly, there's a lot of evidence that a whole bunch of natural ecosystems are unraveling. You can go on and on about the value of any given species for each system. In the end, all those things are what support life on Earth.”

Interview and profile by Jessica Weinberg McClosky, August 2020.

Further Reading

San Francisco Bay Area Inventory & Monitoring Network