Last updated: June 2, 2021

Article

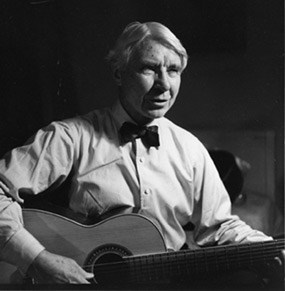

Carl Sandburg and Music

Carl Sandburg Singing Across America

by John W. Quinley

Sandburg Sidebar #2 - January 2020

Many know Carl Sandburg for his written work as poet and Lincoln historian. But Carl was also a consummate performer–delivering lectures, reading poetry, and singing folk songs across America. In 1958, the inaugural year of the Grammy Awards, he was nominated for “best performance documentary or spoken word.” He won the following year for his reading of Aaron Copeland’s “A Lincoln Portrait,” and he received another nomination in 1962 for readings of his poetry. He was in his 80s then, but had been making records for decades, starting in 1926 with “The Boll Weevil” and “Negro Spirituals” recorded on a 45 rpm. Sandburg released 22 records. Twelve of those featured folk songs, mostly from his American Songbag. Seven featured poetry, including excerpts from The People, Yes and a collection of poems for children. He also recorded excerpts from some prose works, including: Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years & The War Years; autobiography, Always the Young Strangers; and his children’s tales, Rootabaga Stories.

Folk Songs in American History

During Carl’s childhood and young adulthood, ballads or folk songs were thought to be crude, and unworthy of public performance, literary criticism, or formal preservation. And “with the spread of literacy, the increasing circulation of printed matter, the introduction of phonographs, and the removal of old-time isolation, through the agency of railroad, automobiles, and (in these days) of airplanes, the singing of traditional songs played a lesser role,” writes Louise Pound in American Songs and Ballads. Sandburg’s pioneering and foundational efforts to sing publicly and to collect American folk song profoundly helped preserve this important record of our shared past. Garrison Keillor writing in the introduction to a later edition of the American Songbag, called Sandburg a “cultural patriot” who came along at a time when he was needed. Prior to the 1927 publication of the American Songbag, children in public schools mostly sang sentimental songs about home and family, which included moral messages about patriotism, industry, cleanliness, and reverence for God. Sandburg’s effort to share more authentic songs of the people reflected more accurately the full range of American experience.

Development and Lifelong Career in Folk Singing

When did he start singing and playing?

Like so many interests in Sandburg’s life, the origin of his singing and playing leads back to his youth in Galesburg, Illinois. As a boy, Carl made a willow whistle, which is a comb with paper which sounded like a harmonica, and a cigar box banjo. He later bought a kazoo, a concertina, and a two-dollar pawn shop banjo. He paid a quarter for three banjo lessons; one of his friends taught him minstrel and popular songs and ballads; and he took a few lessons from a choirmaster. As a young man, he sang in his college glee club and with a local barbershop quartet.

Sandburg bought his first guitar in 1910 at 32 years of age. It was an ornate parlor instrument sold by Sears & Roebuck. It would be six years before his first book of poetry was published. He wrote his wife Paula, “I forgot to tell you that the S-S [Sandburg – Steichen, a favorite term of endearment] now have a guitar and there will be songs warbled and melodies whistled to the… thrumming of Paula-and-Cully’s new stringed instrument.” When he added folk songs to his lectures, he drew larger and larger audiences, saying “If you don’t care for them and want to leave the hall it will be all right with me. I’ll only be doing what I’d be doing if I were at home, anyway.” They stayed “and for the rest of his prolific and long life, Sandburg warbled songs and whistled melodies to the thrumming of various guitars at home, on stages across the country, at gatherings with friends, and on phonograph recordings” (Golden, 1961, p. 79). The moniker “the old troubadour” given to Carl by his long-time friend, architect Frank Lloyd Wright, stuck with him all his life.

Where did he find his songs?

A young Sandburg collected songs from friends and folks he met while working numerous jobs around Galesburg and as he traveled as a hobo and as a door-to-door salesman. “He was becoming a keen listener and observer, filing away the rhythms of a diverse language and the faces of the men who told him their stories, false or true” (Niven, 1991, p. 35).

As he sang and lectured throughout America, his musical collection grew further. There were songs of rural and city life, wars, labor and unions, gospel, farmers and cowboys, immigrants, love, death, and nonsense. Literary colleagues, union organizers, college students and professors, and obscure 19th-century songbooks added to the collection.

What was his singing and playing like?

Sandburg had natural instincts as a performer, and he genuinely liked his audiences and his contact with them. There was a haunting quality to his voice, which he delivered with impeccable timing. Journalists and longtime friend Harry Golden shared that “I’ve heard him sing in a huge auditorium in a whisper, and yet the entire audience sat silent, spellbound.” Chicago Daily News colleague, Lloyd Lewis, remarked that, “Sandburg may not be a great singer, but his singing is great. He is the last of the troubadours; the last of the nomad artists who hunted out the songs people made up, and then sang them back to the people like a revelation.” “For every song that he sings there comes a mood, a character, an emotion…you see farmhands wailing their lonely ballads, hill-billies lamenting over drowned girls, levee hands in the throes of the blues, cowboys singing down their heads, barroom loafers howling for sweeter women, Irish section hands wanting to go home, hoboes making fun of Jay Gould’s daughter. The characters are real as life, only more lyric that life ever quite gets to be” (Niven, 1991, p. 446).

Sandburg accompanied himself on a guitar with no additional instruments. He strummed with two-fingers and, although he knew 10 to 12 chords, he stayed basically within two keys, A and C. Even after classical guitar icon, Segovia, gave Sandburg a few lessons and composed a little practice piece “for my dear Sandburg to teach his fingers as if they were little children,” Sandburg’s style remained simple, but perfectly matched to his delivery. Sandburg sarcastically said of his playing, “If I’d gotten a prison sentence, I’d probably have become pretty good on the guitar.” Sandburg dedicated a poem to Segovia, titled, “The Guitar,” which Sandburg described as “A small friend weighing less than a newborn infant, ever responsive to all sincere efforts aimed at mutual respect, depth of affection or love gone off the deep end. A device in the realm of harmonic creation whose six silent strings have the sound potential of profound contemplation or happy-go-lucky whim.”

How extensively did Carl perform?

Sandburg became more and more in demand on stages and in halls across America. He lectured, read, and sang at colleges, women’s clubs, lyceums, conventions, poetry societies, and more. Carl would often be gone from home, performing for four or five months at a time. By the late 1920s, Sandburg estimated that he had performed at about two-thirds of the state universities in the country. In 1929, he delivered the Phi Beta Kappa lecture at Harvard and recited an original poem written for the occasion. After getting the nod from such a prestigious institution, he said, “Harvard has more of a reputation to lose than I have.” Later that same year at the anniversary of the Lincoln Douglass debates in Galesburg, he spoke to a crowd of 25,000. In the fall of 1936, Sandburg gave 30 lectures in 70 days, traveling through a dozen states and Canada. In 1938, in a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Sandburg told the president to “expect me someday at the White House door with guitar, for an evening of songs and of stories from the hinterlands.” During the 1950s while he was in his 70s, Sandburg continued to perform extensively. He gave concerts to an audience of 9,000 at the University of California and performed in front of 3,000 admirers at the Genial Federation of Women’s Club in Asheville. Sandburg was so much in demand that he turned down hundreds of invitations to speak each year, holding sacrosanct time for his poetry, biography, journalism, and other pursuits, regardless of monetary considerations.

Lecture fees were a large part of Sandburg’s income. In his early days as a journalist in 1914 Chicago, he earned a salary of $25 a week, but he could earn as much as $100 per lecture; by the end of the 1920s, he earned $7,000 in speaker fees. In the 1950s and 1960s, he commanded large fees for his appearances on television, for which he was in great demand. At nearly 80 years of age, he received $10,000 ($90,000 in today’s costs) to give an address at the Chicago Dynamic Week and read an original poem.

The American Songbag

Sandburg was nearly 50 years old when he published The American Songbag in 1927. The volume contained lyrics, piano accompaniment, and historic commentary for 280 folk songs–100 of which had never been published before. The American Songbag quickly became a standard in households across America, and it remained in print continuously for more than seventy years.Sandburg called the book “an All-American affair, marshaling the genius of thousands of original singing Americans.” He said that “the collection could hardly be called poetry in its lofty sense, but they said, by other routes, what his poetry says.” These songs and Sandburg’s poetry chronicle the customs and lives of the early twentieth-century American melting pot.

Sandburg describes his work further: “There is a human stir throughout the book with the heights and depths to be found in Shakespeare. A wide human procession marches through these pages. The rich and the poor; robbers, murders, hangmen; fathers and wild boys’ mothers with soft words for their babies; workmen on railroads, steamboats, ships; wanderers and lovers of homes, tell what life has done to them.”

In 1950, at 72 years of age, Sandburg published a new edition called the, New American Songbag. Bing Crosby wrote the introduction.

Influence on American Folk Music

The American Songbag established Sandburg as both an important singer of folk songs and a critical advocate for the preservation and collection of these songs. As early as 1921, Carl wrote, “This whole thing is only in its beginning, America knowing its songs…It’s been amazing to me to see how audiences rise to ‘em; how the lowbrows just naturally like Frankie an’ Albert while the highbrows, with the explanation that the murder and adultery is less in percentage than in the average grand opera, and it is the equivalent for America of the famous gutter song of Paris—they get it.”

The Songbag first published many tunes now considered folk song standards, including: the “Ballad of the Boll Weevil,” “C.C. Rider,” “The John B. Sails,” “The Weaver,” “Casey Jones,” “Shenandoah (as the Wide Mizzoura),” “Mister Frog Went A-courting,” “The Farmer (Is the Man Who feeds Them All),” “Hangman,” “Railroad Bill,” “La Cucaracha,” “Halleluiah, I’m a Bum,” “Midnight Special,” “The House Carpenter,” and “Frankie and Johnny.” These songs first inspired such legends as The Weavers, Woody Guthrie, and Burl Ives, and later on, The Kingston Trio, Pete Seeger, Leadbelly, and the New Lost City Ramblers. Later 20th Century folk, popular music, rock, and country music artists also recorded songs from the Songbag. Among these were the Beach Boys, Johnny Cash, Peter, Paul, and Mary, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Dan Zanes, and Joan Baez.

In 1964, Bob Dylan briefly visited the elderly Sandburg, the man who had inspired Dylan’s poetry and songwriting. Dylan won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016 for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition–a tradition preserved and expanded by the foundational work of Carl Sandburg some 100 years earlier.

Carl Sandburg dedicated the American Songbag, “To those unknown singers–who made songs–out of love, fun, grief–and to those many other singers–who kept those songs as living things of the heart and mind–out of love, fun, grief.” It is fitting that so many carried on this important work begun by the old troubadour and poet of the people.

Sources

d’ Alessio, Gregory (1987). Old Troubadour: Carl Sandburg with his Guitar Friends. New York: Walker and Company.

Altman, Ross (2018, October 28). Carl Sandburg: America’s First Folk Singer? Retrieved from https://folkworks.org/columns/how-can-i-keep-from-talking-ross-altman/all-columns-by-ross-altman/46596-carl-sandburg-america--first-folk-singer.

Golden, Harry (1961). Carl Sandburg. Cleveland: The World Publishing Company.

National Park Service (1982). Carl Sandburg Home: Official National Park Handbook.

Division of Publications National Park Service.

Niven, Penelope (1991). Carl Sandburg: A Biography. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Sandburg, Carl (1927). The American Songbag. San Diego: A Harvest/HBJ Book, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers.

Sandburg, Carl (1952). Always the Young Strangers. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Sandburg, Carl (1983). Ever the Winds of Chance. Urbana, Il.: University of Illinois Press.

Sandburg, Margaret (editor) (1987). The Poet and the Dream Girl: The Love Letters of Lilian Steichen and Carl Sandburg. Urbana: Il: University of Illinois Press.

John W. Quinley is a retired college administrator and instructor in American History. He leads house tours at Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site. You may reach John here.