Last updated: October 17, 2020

Article

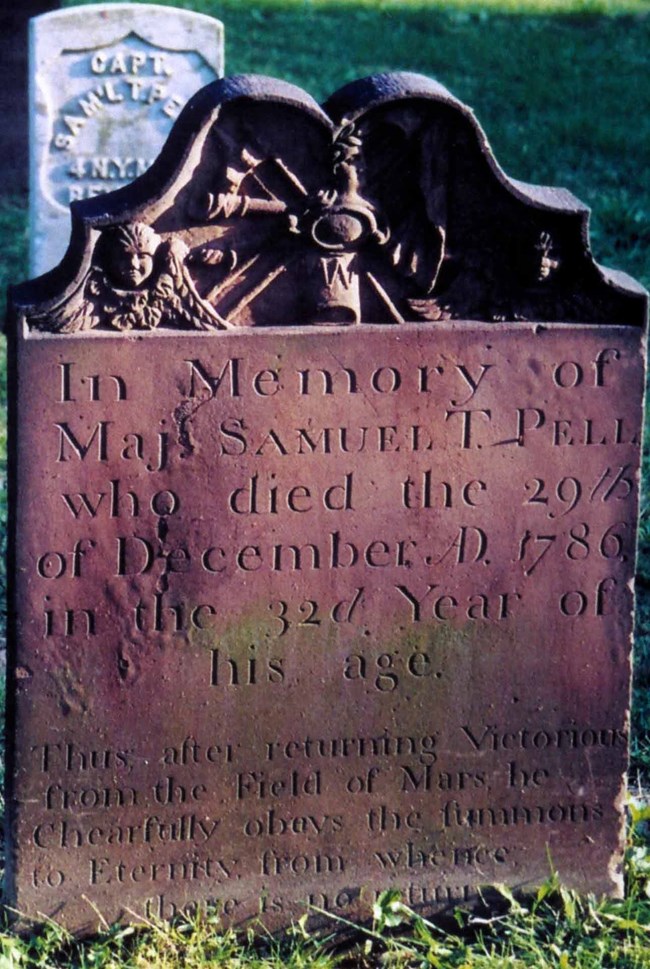

Samuel Treadwell Pell: Continental Army officer buried at St. Paul's

The support for the Patriot cause among wealthy families, and the able service of many of their sons as junior officers -- often despite a lack of previous military knowledge -- was one of the reasons for the success of the American Revolution, as reflected in the experience of Samuel Treadwell Pell, who is buried in the historic cemetery at St. Paul’s.

The future American officer was born July 26, 1755, in Pelham, and died in that town, located a few miles from St. Paul’s, unmarried, on December 29, 1786, as indicated on his gravestone, “in the 32nd year of his age”. At the age of twenty, he joined the Continental army and on the 28th of June he was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the 4th New York Regiment under the command of Colonel James Holmes. This was a year before independence when enthusiasm for the Patriot cause swept Westchester County and the rest of America in response to the initial fighting with the British at Lexington-Concord in Massachusetts.

Pell’s commission was handed to him by prominent New York political leader Gouverneur Morris and on August 11 he was promoted to Lieutenant. Lieutenant Pell was part of Major General Richard Montgomery’s 1775 expedition to Quebec, intent on making Canada the 14th state. Two armies, one under General Montgomery and one under Colonel Benedict Arnold, converged on Quebec and lay siege to the town during one of the worse winters on record. The attack on New Year’s Eve was unsuccessful, killing Montgomery and wounding Arnold and forcing the American army to retreat back to northern New York.

Grave losses, desertions and the expiration of enlistments led to the reduction of New York regiments from five to two and on November 21, 1776, Samuel Pell was promoted to Captain in Colonel Van Cortlandt’s 2nd New York. It was in this body of troops that he would serve out the rest of the war. Pell commanded the fourth company of the 2nd New York and distinguished himself in 1777 at the Battle of Saratoga. Here, the Americans captured an entire British army, thus creating a great victory and one of the turning points of the Revolution.

As a result of this triumph, the budding United States was openly recognized by France which also provided money and weapons. Eventually, French aid would include an army placed under Washington’s command and coordination with a French fleet. Also in 1777, Pell was part of the army that marched to the relief of Fort Stanwix in Rome, New York. Later, under Major General John Sullivan, he was part of the army that marched into Indian territory, fighting against and burning villages and crops of the Iroquois, who were allied with the British.

Officers like Pell were expected to pay for their own uniforms, weapons, food and drink, a major reason why they usually came from the wealthier sector of American society. Additionally, men from the upper crust of colonial life were educated and accustomed to leadership. These faculties made them equipped to navigate military paper work and learn their trade as officers by reading books and treatises on the subject. Superior education also allowed them to effectively communicate the Patriot cause and keep that spirit instilled in their men, even during the darkest and most difficult times of the conflict.

Pell also suffered through the harsh winter encampments of Valley Forge (PA) and Morristown (NJ). After the war he became a member of the Society of Cincinnati, an organization of officers who served in the Revolutionary War. He returned home and settled on his portion of the family’s vast landholdings in Pelham, assuming the role of a country patrician until his death three years later caused by injuries sustained by the fall of his horse. His name appears on the Half-Pay Roll.

Samuel Treadwell Pell knew the joys of victory and the agonies of defeat, both in his military campaigns and, apparently, in his love life. When his regiment was posted to western New York, the captain and one of his men, a fifer, risked capture behind enemy lines to spend the night with some willing young women in their home while their parents slept. According to local tradition, after the war and upon his return home to Pelham, his fiancée and cousin, Mary Pell, an ardent Loyalist, refused to marry him, despite a pre-war engagement. Mary Pell would not allow anyone “with the scent of a rebel” near her.

At the end of the Revolutionary War all commissioned officers were advanced one grade in rank, which is why Captain Samuel Treadwell Pell is buried with the rank of Major carved into his stone. Pell’s impressive sandstone grave marker, a few rows behind the church, reflects his military service, with a Trophy of Arms chiseled into the top and an allusion to the Roman God of War in his epitaph, which reads: “Thus after returning victorious, from the field of Mars, he cheerfully obeys the summons to eternity from whence there is no return.”