Last updated: January 20, 2023

Article

Roger Williams: Rebel, Revolutionary, Radical

140 years before the American Revolution, a minister named Roger Williams created a revolutionary form of government. In a place called Providence, the power of government came not from God, but from the consent and power of the people who lived there. In fact, God would not be a part of this new government that Williams and his neighbors created at all. Instead, participation in a religion would become a personal choice. This notion of “liberty of conscience,” as Williams called it, meant that church and state would remain separate.

Discover how the ideas put forth by Williams would become part of the formation of the Republic, influencing such important words as the Preamble to the Constitution of the United States, which starts with three simple words: “We the People...”

A Life of Rebellion

Born in England around 1603, Roger Williams was educated at Cambridge and ordained as a minister in 1629. However, he would soon become disillusioned with his faith. Like the Puritans who would colonize the area known to the English as Massachusetts Bay Colony, Williams believed that the Church of England was moving increasingly in the direction of the Roman Catholic Church. He argued that the Church needed to be simplified and purified. This was a dangerous belief for the time. Williams and other Puritans knew that they would not be safe in England for long. Church and state were intertwined in England, and the punishment for dissent was severe. Execution for their religious beliefs was a real possibility.

In 1630, John Winthrop and around a thousand other Puritans fled England for the land that was to become the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Roger and his wife Mary arrived a year later. Upon his arrival, Williams was greeted with a warm welcome, even being offered a ministry position. Williams, however, declined – he believed that the Puritans needed to separate entirely from the corrupted Church of England. This belief put him at odds with Winthrop, now leader of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and drove Williams to move to Salem, a more moderate settlement. However, his preaching continued to get him into trouble, and Williams again moved to the separatist settlement of Plymouth.

Williams did not conform at Plymouth either. Here, he spoke out against the practice of paying ministers with public tax dollars and fines. Instead of preaching, Williams would trade English goods with the local Indigenous people, the Wampanoag and Narragansett. It was here that he learned the Algonquian language of the Wampanoag and Narragansett. Williams also developed mutual respect and friendship with Massasoit, Chief Sachem of the Wampanoag and Canonicus and Miantonomo, Chief Sachems of the Narragansett.

When Williams returned to Salem, it was not as a minister, but as a trader. However, Williams continued to preach outside the established Church in Salem, speaking out against the belief that English colonists had the right to Native American lands, and arguing for the separation of church and state. For Williams, the “First Table” laws, or the first four of the Ten Commandments, were not to be enforced by the government. Instead, they were matters of individual conscience, or liberty. This directly contradicted the legal foundations of the government of Massachusetts Bay Colony.

As a result, Williams was charged with “new and dangerous opinions against the authority of the magistrates” in October of 1635. Faced with the possibility of deportation, and knowing the stakes were high, Williams fled Salem and Massachusetts Bay Colony to avoid arrest, leaving his wife and young children behind. Alone in a blizzard, Williams made his escape on foot. He was eventually found by a Wampanoag hunting party, who brought him to the home of Massasoit where he was welcomed and sheltered through the winter.

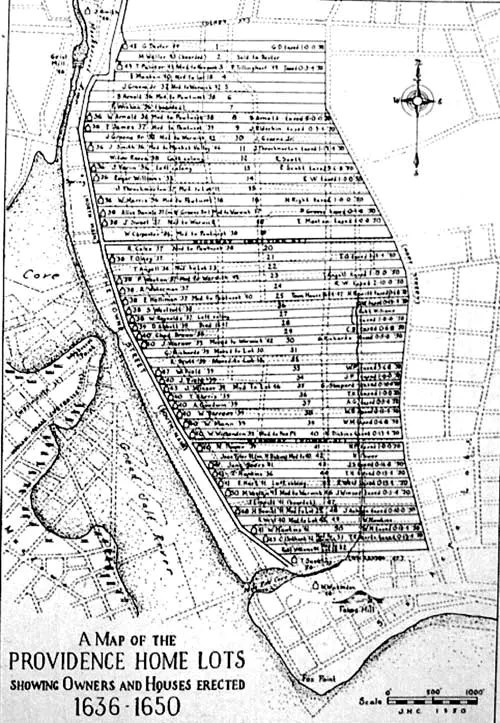

In the spring, Williams and some of his followers moved to the land that would become Providence. Unlike many colonists of his day, he negotiated a settlement for the land with the Narragansett Sachems Canonicus and Miantonomo. Williams did not believe that the English settlers were entitled to the land. While Williams and his followers were offered sanctuary and the opportunity to settle the land, in return, the Narragansett Sachems would be allowed to take any English trade goods they wanted. Once Providence was established, Williams sent for Mary and their two children. After years of controversy and conflict, Williams and his family were ready to start over, away from the watchful eyes of the Puritan authorities.

An Experiment in Government

Providence was a different kind of settlement than Massachusetts Bay. Every two weeks, the settlement would hold a meeting of the heads of households. Unlike colonies such as Massachusetts, there was no requirement for church membership to attend these meetings – every head of household, male or female, was given that right. Furthermore, collected taxes were not to be used to support any church. Freedom of religion was an individual decision, an individual right.

Over the course of Roger Williams’s life, Rhode Island became a refuge for those “distressed of conscience.” It was host to the first Baptist Church, the first Synagogue, and the oldest Quaker Meeting House in America. His ideals and legacy would also be cemented in the First Amendment of the United States Constitution, which declared that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

A review of Williams’s legacy is incomplete without considering the events that took place in the twilight years of his life. In 1675, King Philip’s War broke out in southern New England. The onset of King Philip’s War would see the burning of Providence by a coalition of Indigenous peoples. Despite his steadfast belief in individual liberty, Williams also believed it was justified to enslave Indigenous people as punishment in war.

When Williams first came to the area known as Moshassuck, he saw divine providence. The historical record reminds us that human generosity was at work. Williams was given sanctuary by Indigenous people who allowed his experiment to thrive. After the war, Williams lived with family, having lost his own home to fire. He did not survive long enough to see the town begin to rebuild. Though the exact date of Williams’s death was not recorded, it occurred sometime between January and March of 1683.

A Place for Ideas

The name Roger Williams graces many buildings and institutions in the state of Rhode Island. Williams’s story was elevated to national significance, however, during another key period of conflict.

Roger Williams National Memorial was established in 1965, a year after the Civil Rights Act was enacted. During the Civil Rights movement, questions about equality and civil liberty were making headlines around the nation and the world. Who were “the people” mentioned in the United States Constitution? Were all people entitled to a voice?

In Rhode Island, most people remained disenfranchised, or unable to vote, for decades after the American Revolution. The Royal Charter of Rhode Island only granted voting rights to free white men who owned property, and excluded Indigenous people, African Americans, and women. After the Dorr Rebellion, voting rights were extended to all free men, white or Black, who could pay a small poll tax. All women and members of the Narragansett tribe were prohibited from voting until 1917 and 1924. The passing of the 1965 Civil and Voting Rights Acts enshrined these protections in federal law.

Roger Williams had wrestled with these questions and concepts over three hundred years earlier, believing that above all, the people were the foundation of civil power. He extended civil equality to all heads of households in Providence, regardless of their gender or faith, and adamantly protected their right to live their beliefs and participate in government.

Williams was a revolutionary – he envisioned a world in which liberty of conscience and religious freedom were individual matters that could not be legislated or enforced by a government. He created a colony where this right was protected, and civil liberties were upheld for all. The men we know today as our Founding Fathers would be inspired by these ideas and enshrine them in the Constitution. This Revolution was incomplete and imperfect. Many have been left out of its sweeping scope. The Constitution’s opening phrase, “We the People,” remains a call to action, a reminder of the source of government’s power. The ideas Roger Williams promoted about civil liberty and faith in his colony continue to change, evolve, and expand in our nation today.