Last updated: May 17, 2021

Article

Roads, Model T’s, Tourists, and Tea Rooms

Article from the proceedings from Are We There Yet? Preserving Roadside Architecture and Attractions, April 10-12, 2018, Tulsa, Oklahoma. Watch a non-audio described version of the presentation on YouTube.

Roads, Model T’s, Tourists, and Tea Rooms

By Cynthia Brandimarte, Historic Sites and Structures Program, Texas State Parks/Texas Parks and Wildlife Department

Abstract

This is the day of the Tea Room! The automobile has eliminated conditions of time and distance and merry parties of both old and young, in a sensible quest for diversion and fresh air, are whirling through the country from morning until evening.[1]

As this enthusiastic remark suggests, Americans were getting out and combing the countryside in their new automobiles during the early decades of the 20th century. This experience was made possible by tandem artifacts: the automobile and the tea room. Journalists celebrated the nation's new leisure mobility and noted that “'the cup that cheers, daintily served, adds the crowning touch to many an outings, and tea rooms nowadays are almost universally included in our itineraries."[2]

Tea rooms have attracted limited attention by scholars and researchers during the past several decades. Authors have narrated the trajectory of the tea room, tracing its origins in the U.S. from the late 19th century through its wane in the 1940s. Some published works mention tea rooms as a passing chapter in the history of American foods and focus on recipes and menus. Some studies treat tea rooms as gendered space or as the first step in the feminization of food service in this country. Others address the growing practice of American workers to eat outside both the home and the workplace. Still others describe the stylish interiors of tea rooms. No matter the focus, much of the attention has been on urban tea rooms. Those in cities often are considerably better documented than those in rural areas; some were located in notable buildings and some were even designed by architects.

This paper highlights roadside tea rooms during the 1920s in the wake of Theodore Roosevelt’s Commission on Country Life and in the context of the Country Life Movement, along with the associated Good Roads Movement. In brief, Roosevelt's Commission sought to bring the benefits of cities to rural communities and bring so-called country values to cities. Good roads were a key part of making this exchange work. Urban travelers exploring the countryside would need refreshments and conveniences, which tea rooms could provide. Thus, improved roads boded well for roadside tea rooms. These vernacular buildings drew motorists and tourists to the road with a new confidence, and their legacy is important to preserve in America’s landscape heritage.

Introduction

Some years ago I wrote about tea rooms as part home and part business establishments that American women used strategically and creatively to occupy public spaces by extending their domestic talents of cooking, entertaining, and decorating.[3] This year’s conference theme motivates me to look at tea rooms anew and examine the rural subset of these eateries through the prism of roadside architecture. I want to place them in the context of American landscape history and urge their further identification, interpretation, and preservation.

Overview

The term "tea room" covered a diverse collection of eateries; one could have visited all of them without tasting a dish the same as in other tea rooms, nor dined in a room decorated the same way as others. Patrons found tea rooms in downtown department stores, bohemian locales such as Greenwich Village, suburban houses on main thoroughfares, and farmsteads located on roads connecting rural communities. “Tea room” labeled an array of restaurants located in geographically diverse places from Maine to California and operated by people who had little else in common. The establishments were intended to serve many different purposes—from providing young female mill workers a livelihood after a mill had closed, raising money for a church, or simply providing a personal income. More than middle-class women patronized them: shop girls and shoppers, members of bridge clubs; schoolchildren; and men as well as women. In an era of increasing standardization, operators of tea rooms tried hard to make them “unique," often successfully.

Some restaurants earned the “tea room” label. Most tea rooms were operated by women, not infrequently two women who had chosen to combine their complementary skills in the restaurant business. Because many tea rooms were in large standing buildings, some had to be altered, even transformed, by female elbow grease and decorative inspiration. More than other conventional restaurants, tea rooms and their operators effectively mediated between dining in private and dining in public by applying the rhetoric of domesticity to food eaten away from home and by creating a public approximation of home atmosphere and home cooking.

Library of Congress

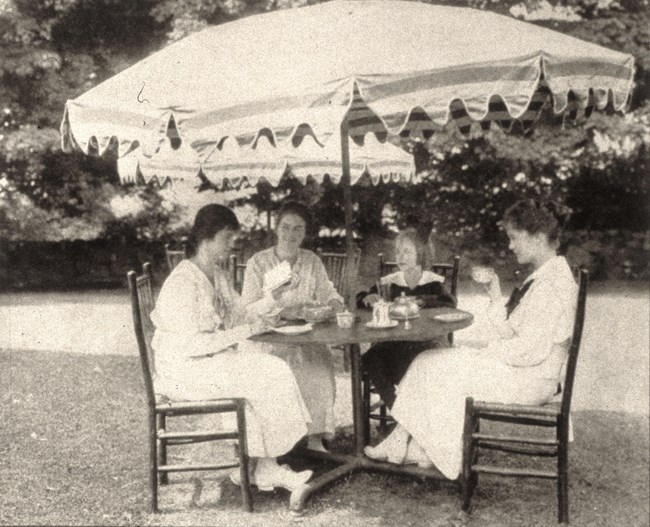

We know about early 20th-century tea rooms by virtue of a sizable literature about them. Between 1915 and 1930 illustrated articles about the management and menus of tea rooms abounded in periodicals like Ladies' Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, Journal of Home Economics, Delineator, House Beautiful, and Country Life in America. During the early 1920s, there was even a monthly magazine titled Tea Room Management.[4} Articles stressed that not only were some tea rooms in homes or looked like homes; they felt like homes. Poems, photographs, and printed articles portrayed intimates enjoying refreshments in settings with cozy furnishings, charmingly mismatched ceramics, colorful fabrics, flickering fireplaces, and snoozing cats.[5]

Tea rooms felt, in short, like homes in a world that was increasingly impersonal. Young women and men had left farms for cities ill-prepared to house them; immigrants without places to live had arrived in record numbers; urban dwellers who felt cities uncaring had carved out suburbs for themselves near workplaces. In this flux, urban and suburban tea rooms were convivial places for people to gather, and countryside tea rooms provided motorists and other travelers with approximations of home.

There is a fair amount of agreement about the origins of tea rooms. Department stores like Wanamaker’s and Macy’s appear to have followed the lead of French department stores in providing women shoppers with a place to refresh and dine. American women traveling to London during the 1890s observed what was purported to be the first “tea shop” chain—the ABC tea shops. Knowledge of Catherine Cranston’s Glasgow tea rooms, decorated by architect and furniture designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh, spread internationally.

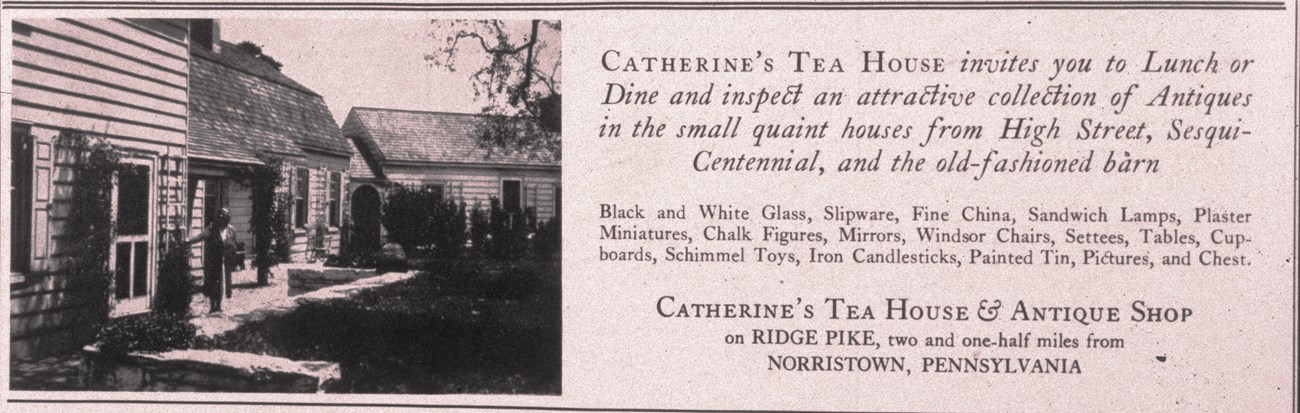

Author’s collection

Tea rooms in American department stores formed one pattern, but what about independently operated tea rooms? Did rural tea rooms come first and urban ones later? When did urban tea rooms begin to outnumber rural ones? In 1908 a writer declared that most tea rooms were in the countryside, “but farsighted women reasoned that if people welcome tea room atmosphere in the country in the summer, they would enjoy the same service in the winter in the city.”[6] By 1923 urban tea rooms may have outnumbered rural tea rooms.

Tea Room Contexts

No matter its location, the tea room benefitted from tea’s aristocratic overtones and from enthusiasm for all things Japanese, including tea and “tea houses.” Tea rooms were legitimized as suitable businesses for women—a natural development of inn keeping. These connotations, along with two important cultural backdrops – the movement for women’s voting rights and Prohibition—helped tea rooms to spread and flourish. In both respects, the pivotal year was 1920.

For nearly a century before passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, American women rallied support for three principal reforms —abolition, temperance, and suffrage. From Seneca Falls, New York in 1848, throughout the late 19th century, women lobbied for social justice and a greater role and voice in the body politic. All was not smooth sailing, with disagreements about the tactics, the timing of federal or state reforms, and the priorities reform issues should be given, most notably during the Civil War. There was little consensus about which barriers most limited women’s rights—family responsibilities, a lack of educational and economic opportunities, or the absence of a voice in political debates.

Ignited by Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony, the movement eventually coalesced and found a constituency late in the 19th century when the nation experienced a surge of volunteerism among middle-class women. It brought together activists in progressive causes, members of women’s clubs and professional societies, temperance advocates, and participants in local civic and charity organizations. Determined to expand their sphere of activities outside the home, activists legitimized the suffrage movement and provided momentum for it. Women united to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), which melded diverse interests and shunted disagreements aside. The nation’s need for women’s support during World War I, made clear by President Woodrow Wilson, gave women added leverage.[7]

Prohibition helped to popularize tea rooms. The 18th Amendment to the Constitution, passed by Congress in 1920 and implemented by the Volstead Act, banned the production, importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages. However, opposition blaming Prohibition for causing crime, lowering local tax revenues, and imposing rural Protestant values on urban Americans grew steadily. The 21st Amendment repealed Prohibition in 1933—but not before a variety of restaurants had become established and popular.[8]

Before Prohibition, at the turn of the 20th century, the world of restaurants consisted of hotels, bar-restaurants, and working-class saloons. These were largely male preserves, and primarily only the finer restaurants reserved small, private dining rooms for female customers. Receiving most of their profits from liquor sales, restaurateurs of high-quality establishments could treat their male patrons to expensive meals served in ample quantities.

Library of Congress

The temperance movement had long advocated alternatives to such restaurants, and when Prohibition took effect in 1920 many elegant dining places went out of business. Spurred by Prohibition and ready to profit from it were soda fountains, luncheonettes, cafeterias, and tea rooms. Unlike hotel restaurants, which were often expensive and inconvenient, and unlike cafeterias, which lacked warmth and charm, tea rooms were distinctive and attractive places to eat. As women’s public voice strengthened and Prohibition became law, tea rooms rode with the tide.

Contexts for Rural and Roadside Tea RoomsThe popularity of rural tea rooms stemmed from several factors, among them roads, automobiles, tourism, and the Country Life Movement. A large road system was already in place in the United States when cars became a major mode of transportation in the early 20th century. But roads were narrow, primarily composed of dirt and gravel, and generally followed existing topography. Before 1900, only four percent of the roads were paved, which meant poor and unreliable traveling conditions.

Early colonial routes were mostly natural surfaces to accommodate wagons and they complemented a waterway transportation system. After the federal government’s 1806 construction of the National Road, also known as the Cumberland Road, from the Potomac River at Cumberland, Maryland, and inland to the Ohio River at Wheeling, West Virginia, local governments had to step in to fund and oversee road construction and operation between the 1830s and the 1920s. The federal government had no money to spend on roads and the states had little interest in them. Immigration spurred migration to western areas, and by the late 1880s there were many established routes within and between cities, as well as popular routes for interstate and transcontinental travel. Interest in improving roads took hold in the late 1800s when bicycles proliferated and during the early 20th century when automobiles became more common.[9]

Improving roads involved oiling naturally surfaced roads as a first step, then paving with an asphalt surface as a second. Most paving was done on a small scale until World War I. After the war, the federal government greatly increased its efforts to “get the farmer out of the mud.” The funding mechanism for its improvements was a tax on gasoline sales. In 1916, the US Congress created the Federal Aid Highway Program, which continues today as the basis of federal support of highways.[10]

In 1913 there were some 600,000 motor vehicles in the world, most of them produced in the U.S. The most popular automobile was the four-cylinder, twenty-horsepower Model T. First offered in October 1906, the Model T sold for $825 (in 1908) and was referred to as the “car for the great multitude”—it was easy to drive and easy to repair. Made of light-weight steel, it was designed to clear the bumps in rural roads with its high chassis. By 1912, the Model T runabout sold for $575, less than the average annual wage in the United States. By the time the Model T was withdrawn from production in 1927, its price had been reduced to $290 for the coupe, 15 million units of which had been sold. Mass personal “auto-mobility” had become a reality. The Model T was intended to be “a farmer’s car” serving the transportation needs of a nation of farmers. But its popularity was bound to wane as the country urbanized and as rural regions got out of the mud with passage of the 1916 Federal Aid Road Act and the 1921 Federal Highway Act.[11] Ford was just one of several hundred car manufacturers in the US by the mid-1920s. By 1925, there were more than 17 million automobiles registered in the US.[12]

The Magazine Antiques

Driving these vehicles were tourists, who were newly leisured Americans exercising freedom to enjoy weekend adventures, antiquing, and pleasure rides. The 1920s saw the culmination of a century-long work-reduction movement as labor turned to a five-day work week with shorter workdays. Work hours had been reduced by 16 percent during the two decades before the end of World War I. As organized labor pushed for further reductions, leisure and recreation became public and political issues.

Public recreation facilities such as parks, playgrounds, and community centers expanded at unprecedented rates. National park and recreation organizations flourished. Amusements and commercial recreations (radio and the movies) grew as never before. The automobile opened vistas to a newly mobile public.[13]

Special Collections, Bailey/Howe Library, University of Vermont

Enter Tea Rooms

Tourists venturing out of cities needed a home, not a hotel. As one tea room operator observed, many motorists who rushed through the countryside were not looking for a large establishment where they could eat a multi-course meal at a leisured pace. Instead, she believed that a "typical" motorist wanted a "quiet spot along the highway where he may be quickly served with delicious vegetables fresh from the garden, cool salads, iced drinks tinkling in tall, thin glasses, or the varieties of dainty sandwiches which the wayside tea house affords."[14]

In the literature about rural eateries, there was a conflation of roads, automobiles, and tea rooms (fig. 6). Commentators often mentioned the trio in a single breath or within a sentence or two, as did writer Mary Northend: “Until the automobile was graduated from the class of luxuries into that of necessities, tea-shops were successful only in the large cities. Today they flourish in the smallest and flaunt their copper kettles and blue teapots on every broad highway.”[15] Improved roads boded well for the nation's tea rooms. "When a road becomes paved," one enthusiast declared, "that road begins to wake up and take a new interest in life, and the field for rural tea houses expands."[16] It was as if roads married automobiles and together they begat tea rooms.

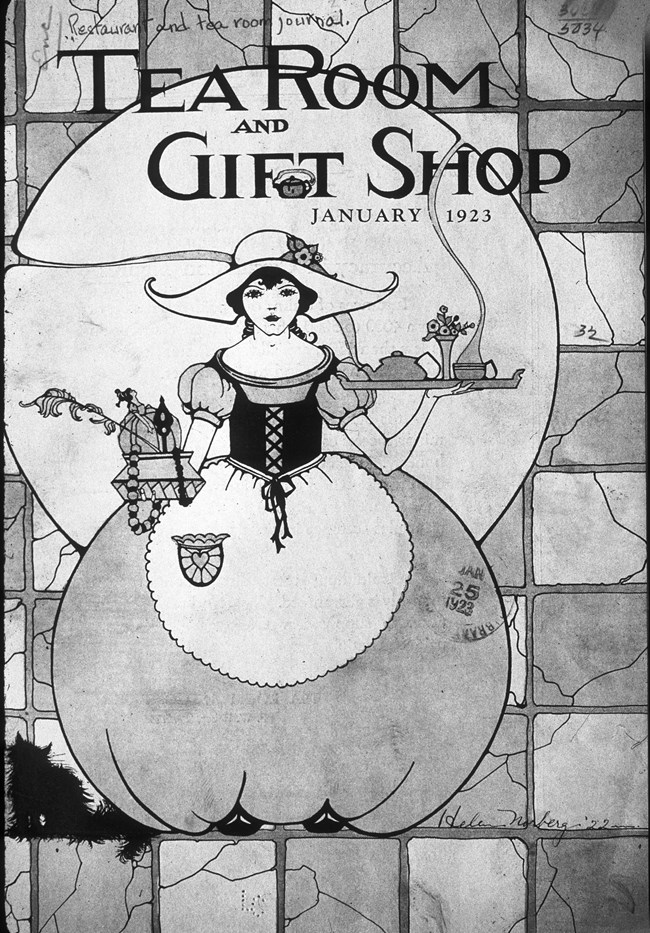

Contributing to what I am calling the conflation of roads, vehicles, travel, and tea rooms was a man named Frederick W. Baker. For him, boundaries between motorcars and restaurants were rather fluid. Baker was “formerly connected with Good Roads and the McGraw–Hill Book Co.” He began his tenure as the tea-room magazine’s owner and publisher by changing the name from Tea Room Management to Tea Room and Gift Shop. Joining him in the new endeavor was M.O. Baker as Associate Editor.

For some tea room patrons, the makes and models of vehicles parked at a tea room functioned as an index to menu prices and statuses of the clientele. As a patron wryly commented in a tea room guestbook: “Look at the price list and watch the Fords go by.”[17] Some tea rooms, especially those featured in House Beautiful, subscribed to the philosophy that "people who stop and grumble at prices are usually not the desirable kind." Instead, "the right kind of people realize that the season is short, and that the thing cannot be done well at a lower price."[18] Such comments assured magazine readers that they would be among their equals at most roadside tea rooms. We can only imagine motorists who decided whether or not to stop by scoping out the automobiles in a tea room’s parking lot, seeking “Rolls Royces” and avoiding pedestrian Fords, or vice versa.

Of course, motorists might assign chauffeurs the task of evaluating a tea room’s clientele according to automobile makes and models. To accommodate hired drivers, one clever tea room operator had a special room for them where they could be served "Chauffeur's Tea." She boasted that "In this way many dollars were added to the tea room's coffers."[19] A smart marketer, she noted that "[A]s Chauffeurs are but human, they will surely be more likely to turn up when possible near this tea house, rather than in the vicinity of one where they will be expected to play wooden Indian while their employer is 'teaing.'"[20]

Tea room fare could refresh the weary traveler, but it could also be the enemy of tourism. Yes, the eateries could make the “rest” part of travel an end in itself (fig. 8); but there was such a thing as being too comfortable amid the pleasant surrounds and tasty refreshments. More than one observer noted that vacationists would arrive at a scenic or historical destination, only to stop and enjoy the tea room hospitality for so long that they missed viewing the sites. [21]

Periodicals packaged roads, autos, tourists, and tea as opportunities: for travelers, comfortable and healthy excursions; for tea room owners or aspiring owners, a pleasant and profitable business. Others who benefitted were transporters who pushed for good roads and automobile manufacturers who pursued expanded markets. Still others, perhaps less obvious, had a stake in the success of the roadside tea room and saw its value for farming communities and villages. These were early 20th-century reformers concerned about rural life: educators, economists, journalists, and rural sociologists who were variously involved in the Good Roads, City Beautiful, and Country Life movements. [22]

The Country Life ContextIn 1908 during the waning months of his administration, President Theodore Roosevelt appointed seven men to constitute a Commission on Country Life. They were charged, with a deadline of four months, to report on the "existing social, economic, and education conditions in the country, the means available for remedying deficiencies, and the best methods to use to organize a permanent investigation."[23] After conducting mail surveys and interviews, touring parts of the country, and encouraging rural residents to hold local meetings to discuss rural problems, the commission published The Report of the Country Life Commission (1911), which became a manual for the Country Life movement’s activities for a decade or more.[24]

Spurred by a fear that the countryside was permanently losing its population to cities, the commissioners generally agreed that "something deficient in rural life was driving people to the cities,” but they differed about what it was. Several thought that farmers needed to operate their farms more profitably, like businesses; others believed that the cause of disaffection with rural life was the host of social issues that plagued the farm family, especially women in them.

Regardless of causes, Roosevelt's Commission wanted to bring benefits of the cities to rural communities and extend country values to cities. Bad roads tended to stand in the way. So in addition to calling for road improvements, the Commission recommended creating cooperative organizations among farmers to advance their social and economic interests,[25] bolster the teaching of scientific agriculture in rural schools, and coax rural churches from doctrinal religious issue toward the social mission of improving community life. [26]

House Beautiful

Tea rooms appeared to satisfy both those who wanted city money to flow to the countryside and those who wanted to relieve the farm wife of some daily drudgeries. Country Life exponents reasoned that because they needed refreshments and conveniences such as rest rooms, excursionists coming from cities could bring profits to farmers who raised the food served at tea rooms.[27] In turn, operating a tea room, placing handmade craft items in the its gift shop on consignment, or enjoying tea rooms with rural neighbors would be respites from farm women’s monotonous routines and chores.

That sense of larger purpose infused some rural tea rooms and was commented on in the press. The editor of House Beautiful, Walter Dyer, wrote an article titled, "A Community Tea- House: A Simple Clubhouse in Villages or the Real Country, One Solution of the Problem of How to Bring New Interests and Human Contact into the Life of the Farmer's Wife.”[28] He described something quite different from a prosaic tea room:

Your college graduate or ex-school teacher or naturally gifted lady of penurious leisure builds a bungalow of cypress, stained brown or green, or renovates and old shingled cottage, and plants a crimson rambler beside the door. She furnishes it inexpensively with rag rugs, stained chairs and tables, table ferns and a plate-rail, and an obvious color scheme. She hangs out a sign, sets the kettle over to boil, and waits for the passing automobile or the bored resident of the summer hotel. She also runs a gift shop, putting in a consignment of tinted photographs, arts-and-crafts goods, and 'novelties.' If her muffins and tea and Sally Lunns and Waldorf salad are very good, and she has chosen a fortunate location, someone will come along with a camera some day and she will be written up for the woman's page, and will live happily ever after.[29]

Your college graduate or ex-school teacher or naturally gifted lady of penurious leisure builds a bungalow of cypress, stained brown or green, or renovates and old shingled cottage, and plants a crimson rambler beside the door. She furnishes it inexpensively with rag rugs, stained chairs and tables, table ferns and a plate-rail, and an obvious color scheme. She hangs out a sign, sets the kettle over to boil, and waits for the passing automobile or the bored resident of the summer hotel. She also runs a gift shop, putting in a consignment of tinted photographs, arts-and-crafts goods, and 'novelties.' If her muffins and tea and Sally Lunns and Waldorf salad are very good, and she has chosen a fortunate location, someone will come along with a camera some day and she will be written up for the woman's page, and will live happily ever after.[30]

Like other Country Life enthusiasts, Dyer accepted the notion that what was wrong with the countryside was that it was not the city, and that with a little bit of the city, rural folk would be happier where they were. Tea rooms had the potential to mend the rift between producer and consumer and solve “the old economic problem of bringing the producer and consumer nearer together, and the social question of how to get urban and rural life into closer contact."[31]

In Dyer's opinion, the automobile helped bring urban and rural together, but it had not fully "bridged the gap." He imagined that motorists in a tonneau "glance out admiringly at the old white farmhouse behind its big lilac bushes, and catch a whiff of incense from the kitchen stove," and he lamented that the tourist can only "whiz past never dreaming that the cornmeal drop-cakes that Mrs. Meekins is frying would taste a hundred times better to them than the hotel luncheon they are headed for." He sought to find a place for the two to interact, where "[m]otorist, pedestrian, cottager, and rocking-chair invalid would find their way thither, or be arrested by the swaying sign."[32]

Dyer said he knew of only one place that came close to filling his bill. But well-off readers of his House Beautiful article would likely have known such places they had visited. While not able to improve the lot of farm women through government action, magazine readers may have been motivated to help rural women via influential women's clubs and urban civic service groups to which they belonged.

Identifying and Documenting Roadside Tea Rooms

I conclude by suggesting tea rooms and Country Life had another, perhaps more tenuous, connection to cultural landscapes. The movement voiced concern about abandoned farms, as well as a commitment to land conservation and community preservation. Its desire to reinvigorate country life—and to some extent vacant buildings, some of them historically important – was in the spirit of “adaptive reuse.”

No matter their location, tea rooms and proponents of them often invoked tradition as a legitimizing factor, appropriating Colonial Revival material clichés, preparing simple foods, and featuring handcrafted gifts. I grant that some establishments were, in fact, built as tea rooms.

For example, the Bungalow Tea Room in Gregoryville, Kentucky, was erected in 1927 just as the newly constructed concrete US Highway 60 was being completed.[33] But many were in existing buildings that were often old and sometimes historic. For example, Knoxville women "opened, cleaned, repapered, and electric-lighted” the abandoned Sevier-Park home, built in 1800.

After gas stoves were installed, the house became a tea room, gift shop, and briefly a war workshop.[34] Consider, too, buildings that did not look like homes, or had not in some time, but were converted into homelike places. The title of one article—"Do You Own a Barn, an Old Mill, or a Tumble-down House?"—illustrated the point that no type of structure was off limits to the tea room entrepreneur. For example, ambitious and creative owners of a Montana homestead realized the potential of their chicken house by turning it into a tea room that served patrons of the "dude camp business."[35] Women all over the country transformed abandoned historical buildings, especially barns and mills, but also houses, into colonial revival tea rooms. The Green Arbor Tea House in Concord, Massachusetts was operated by the “Misses Newman” who transformed a structure into an attractive tea room. Formerly, its first level served as a hen house and its second level as a carpenter's shop.[36]

Located in Concord, the Green Arbor might be an easy tea room to identify and document, if it is still standing, but others are less so. Their ephemeral uses make identification and documentation difficult; for example, some opened only seasonally during summers, and many tea rooms were short-lived, as evidenced in observations like this: “But of the hundreds that spring up comparatively few survive; and to exult over the discovery of a shining new dispense of homemade jam with clotted cream is apt to prove vain. Pass that way a month later, and the chances are that a grimy window will hold a sign, 'For Rent,' and only empty screw-holes will remain to show where once the inviting tea-shop sign hung."[37] Sometimes, a building’s use as a tea room was a mere chapter in a long history. Such was the case of the Sweatt-Ilsley House of Historic New England—its location on Newbury’s most traveled road—which operated as a tea room to weather the hardship of the Great Depression.[38]

I know of no comprehensive list of historical tea rooms in the U.S. To be sure, there are city directories that list restaurants; there is the Green Book and other travel guides. And WPA guidebooks list some tea rooms in scenic tourist locations. HABS is still another place to look. But overall, identifying and documenting tea rooms are local and state undertakings that only eventually could culminate in a national database. Only three are in the National Register of Historic Places: Libby’s Tea Room in Wells, Maine (on Post Road, US Route 1); The Salvation Army Waioli Tea Room in Honolulu, Hawaii; and Country Tea Room in East Dundee, Illinois.[39]

This has been an introduction to tea rooms and a call-to-arms (or challenge) to locate them in the American landscape. Their messages are rich, for they tell us about how Americans embraced the new technology of the automobile, what propelled them to take to the road, what they enjoyed of the new and what they clung to of the past as they traveled on improved roads, and what conveniences made them comfortable and confident as they motored along. Tea rooms remind us that for those living in 1920s America taking a meal on the road was not all that simple a matter.

Endnotes

1 Florence Spring, "The Green Arbor Tea House," House Beautiful vol. 42 (June 1917): 26.2 "The Tea Room on the Road," The Ladies' Home Journal vol. 34 (May 1917): 39.

3 Cynthia A. Brandimarte, “’ To Make the Whole World Homelike’: Gender, Space, and America’s Tea Room Movement,” Winterthur Portfolio 30, no. 1 (Spring 1995): 1-19. Other authors include Harvey Levenstein, Revolution at the Table (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988) and Jan Whitaker, Tea at the Blue Lantern Inn (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2002).

4 Tea Room Management was published beginning in 1922; the journal later became Tea Room and Gift Shop and by 1925 was known as Restaurant and Tea Room Journal.

5 For example, see M.A. (author) “The Tea Room,” Tea Room and Gift Shop 2, no. 3 (March 1923): 10. The poem first appeared in the New York Sun.

6 “While the Kettle Sings,” Tea Room and Gift Shop 2, no. 4 (April 1923): 13.

7 History, Art & Archives, US House of Representatives, Office of the Historian, Women in Congress, 1917–2006. Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office, 2007. “The Women’s Rights Movement, 1848–1920,” http://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/WIC/Historical-Essays/No-Lady/Womens-Rights/ (December 29, 2017).

8 David Okrent, Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition (New York: Scribner, 2010). “American Spirits: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition,” traveling exhibit by the National Constitution Center and the National Endowment for the Humanities, hosted by the Bullock Museum, September 2, 2017, through January 7, 2018.

9 https://www.nap.edu/read/11535/chapter/2. "2 History and Status of the US Road System." Transportation Research Board and National Research Council. 2005. Assessing and Managing the Ecological Impacts of Paved Roads. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/11535.

10 Ibid

11 http://www.history.com/topics/automobiles Accessed 2107-12-2.

12 https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ohim/summary95/mv200.pdf.

13 https://www.loc.gov/collections/america-at-work-and-leisure-1894-to-1915/articles-and- essays/america-at-leisure/.

14 Mary T. Parfitt and Elsye Wallace Osterman, "Making a Living in the Country," Woman’s Home Companion 49, no. 4 (April 1922): 35-36. The writers opined that tourists who live within a radius of fifty or so miles could be cultivated so that they would become regulars.

15 Winnifred Fales and Mary Northend, “At the Sign of the Tea Room,” Good Housekeeping 64, no. 7 (July 1917): 57.

16 “More Good Highways, More Good Tea Rooms," Tea Room Management 1, no. 5 (December 1922): p. 6.

17 Ruth MacFarland Furniss, "Maple Products A Specialty," Tea Room Management 1, no. 2 (September 1922): p. 11

18 Margaret H. Richardson, “The Story of a Tea-House,” House Beautiful 38, no. 1 (June 1915): 7.

19 Ruth MacFarland Furniss, "Maple Products A Specialty," Tea Room Management 1, no. 2 (September 1922): p. 11.

20 Ruth MacFarland Furniss, “Observations,” Tea Room Management 1, no. 2 (September 1922): 13.

21 For example, Main Johnson, “Tea in the Rockies,” Canadian Magazine 46, no. 1 (November 1915): 57-61.

22 The leaders of the movement were by and large men who, like most Americans born soon after the Civil War, came from farms and villages. Like other Progressives, they tended to be educated, having college degrees when they were not all that common.

23 William L. Bowers, The Country Life Movement in America, 1900-1920 (Port Washington, N.Y.: Kennikat Press, 1974). According to Bowers p. 25, historian of the movement, both sides failed to understand the onward march of industrialization with higher wages among urban employers, shorter work hours, and more social interaction.

24 Liberty Hyde Bailey, Report of the Commission on Country Life, with an introduction by Theodore Roosevelt (New York: Sturgis & Walton Company, 1911). https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001429089.

25 Bowers, p. 65.

26 Belying any implied criticism of country life was the continuing belief in the nobility of the farmer and Jefferson’s agrarian myth. And there was self-interest on the part of the city dwellers who still needed the farmer to grow crops for food.

27 And perhaps would serve as an early incarnation of the buy local trend.

28 Walter A. Dyer, "A Community Tea-House: A Simple Clubhouse in Villages or the Real Country, One Solution of the Problem of How to Bring New Interests and Human Contact into the Life of the Farmer's Wife,” House Beautiful 38, no. 3 (August 1915): 89, xiii.

29 Dyer, p. 89.30 Ibid.

31 Ibid.

32 Ibid.

33 Part of the expanding transportation network that often followed the historic national post roads, Highway 60 was poured along the Midland Trail from Lexington, Virginia to Louisville, Kentucky, by way of Lexington, Kentucky, and was one of the state's newest and most scenic routes. Members of the Gee family saw economic opportunity when they constructed the Bungalow Tea Room, which not only functioned as a restaurant, but also a post office, gasoline station, and general store from the late 1920s until about 1950.

34 Sophie C. Harrill, “The House of a Thousand Memories,” House Beautiful 44, no. 5 (October 1918): 263-65.

35 “Do You Won a Barn, an Old Mill, or a Tumble-Down House?” Woman’s Home Companion 49, no. 5 (May 1922): 27, 98.

36 Florence Spring, “The Green Arbor Tea House,” House Beautiful 42, no. 1 (June 1917): 26-27.37 Fales and Northend, 57.

38 https://www.historicnewengland.org/property/swett-ilsley-house/.

39 http://gis.hpa.state.il.us/pdfs/201471.pdf National Register of Historic Places Nomination for Pine Grove Community Club is related to Country Life Movement. As of February 9, 2018, only three properties listed on the National Register of Historic Places available in states whose records are digitized were identified as tea rooms: https://www.nps.gov/nr/research/index.htm.