Last updated: August 15, 2022

Article

Early Supreme Court Justices Ride the Circuit

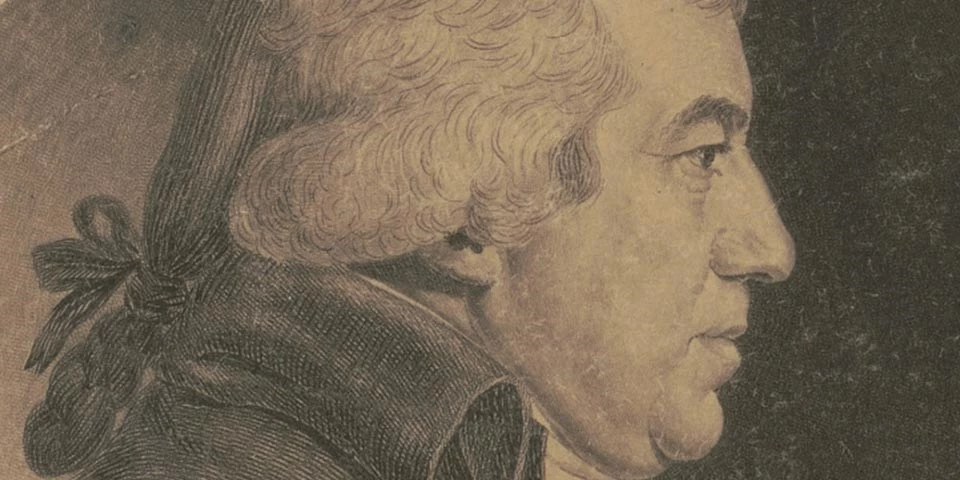

James Iredell by Saint-Memin, 1798 or 1799, courtesy of Library of Congress https://www.loc.gov/item/2007676892/.

Standing in Old City Hall in Philadelphia - where the U.S. Supreme Court held session in February and August each year in the 1790s - it's hard to imagine what life was like for the early Supreme Court justices. Here they shared a courtroom with the Mayor's Court. And, here they enjoyed the comforts that a cosmopolitan city - the temporary capital of the new nation - had to offer. Why did they travel? Just what was a "road trip" like back then?

The Early Federal Court System

The U.S. Constitution established the Supreme Court of the United States, but the Judiciary Act of 1789 established the lower federal courts:

- 13 district courts

- 3 circuit courts

- Eastern

- Middle

- Southern

The Hazards of the Road

The justices traveled in a chiefly rural countryside in the 1790s. It was a land of primitive roads and few bridges. All who traveled were at the mercy of the weather. Justices faced dangers, illness, and harsh living conditions as circuit riders.“The Hon. Judge CHASE very naturally escaped being drowned...He was taken from the river almost lifeless.” -- Philadelphia Gazette, February 3, 1800

Justices spent anywhere from six to nine months on circuit, averaging some 1000 miles for each circuit. In 1792 Justice Iredell suffered a road accident where he injured his leg. He was later robbed while riding circuit. In frail health, he died two weeks before his 48th birthday, worn down by his judicial duties. Iredell's enslaved servant Hannibal also endured the hazards of travel as he accompanied the justice in circuit riding. In April 1798, Justice Iredell wrote to his wife about the difficulties he and Hannibal encountered in trying to pass through a swamp on the way to Circuit Court in Savannah, Georgia. At his slaveholder's direction, Hannibal proceeded first through the swamp waters, stopping just before the water became dangerously deep. Iredell and Hannibal failed to reach Savannah, and the court session was cancelled.

Out of necessity, justices of the highest court traveled and lodged with a whole host of fellow Americans they met along the dirt roads and rivers of a sprawling nation. This mixed medley of classes of people was undeniable proof of a growing democratic spirit. Rooms, food, and service varied in quality at taverns and inns. Rest was not easily achieved in the busy and often crowded public houses. For instance, Justice James Iredell “suffered” when he was forced “to sleep in a room with five People and a bed fellow of the wrong sort." Justice William Cushing once shared a room with twelve other men. If the justices were fortunate, they stayed with friends. They paid their own travel expenses.

In 1793, Congress amended the law, reducing the number of justices riding each circuit from two to one. Designed to allow one justice to stay at home for an entire circuit run, the new law didn't always bring the desired relief for weary justices. Sometimes they had to fill in when their fellow justices were unable to attend sessions.

The Families

“…Suffer not your Spirits to sink; I am in the Course of Duty, and being so, we must bear up under it with Patience and, if possible, with Cheerfulness.” -- Associate Justice William Paterson to Euphemia Paterson, April 3, 1793

John Jay, the first Chief Justice, complained in 1791: “I am now in one [position] which takes me from my Family half the Year, and obliges me to pass to Considerable a part of my Time on the road…” Because of the separation from their families, some justices resigned or declined the appointment. In his resignation addressed to President Washington, Justice Thomas Johnson wrote: “I have measured Things however and find the Office and the Man do not fit – I cannot resolve to spend six months in the year of the few I may have left from my Family…”

Justice William Cushing and his wife Hannah chose to remain together - on the road. They traveled together in a specially outfitted carriage. Hannah Cushing wrote a relative in 1792 about their nomadic existence on the road, saying it made their life like “traveling machines."

Some of the justices had enslaved servants to care for their families and homes while they were away circuit riding. For the enslaved servants traveling with a justice, they too knew the pain of separation from their families.

Circuit Riding Continues...till 1911

Circuit riding continued until 1911. There was one short-lived exception when Congress passed an act abolishing circuit riding for the Supreme Court in 1801. It also established circuit courts staffed by a new group of judges. This “Midnight Judges Act” (so-called because it allowed Adams to appoint judges sympathetic to his party at the close of his administration) was abolished by the incoming president, Thomas Jefferson.

As the country grew, so did circuit riding. Steamboats and trains diminished some of the travel time, but there were still obstacles. In 1863, Associate Justice Stephen Johnson Field had to ride circuit to distant California before the Transcontinental Railroad was completed. Justice Field traveled from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco by way of Panama. On average, the trip took three weeks.

The Judiciary Act of 1869 brought reforms with justices attending their circuit once every two years. The Judicial Code of 1911 finally abolished the need for circuit riding although the justices continued to oversee the circuits.

Sources

Maeva Marcus, James R. Perry, James M. Buchanan, Christian R. Jordan, and Stephen L. Tull. “The Hardships of Supreme Court Service, 1790-1800.” This Constitution, Spring, 1984.Maeva Marcus. The Documentary History of the Supreme Court of the United States, 1789-1800. New York: Columbia University Press, 1985-92.

Linda Greenhouse. “Riding Circuit with Swamps and Yellow Fever.” New York Times, Nov. 2, 1990.

Susan Ballistreri. The Original Supremes. Independence National Historical Park, 2008.

Sebastian Bates. “Riding Circuit: How Supreme Court Justices Can Act Alone.” Penn Undergraduate Law Journal, March 17, 2015.

Winston Bowman. “The Midnight Judges.” Federal Judicial Center.

John Haskell Kemble. “The Panama Route to the Pacific Coast, 1848-1869.” Pacific Historical Review, Vol 7, No. 1 (March 1938), University of California Press, 1938.