Last updated: December 30, 2021

Article

Richard Shute: The man under the oldest legible gravestone at St. Paul's

National Park Service

Richard Shute – The Man Under the Oldest Legible Gravestone at St. Paul's

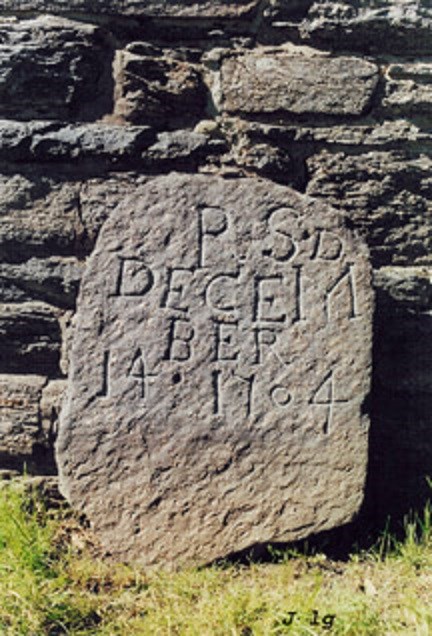

A stone grave marker with the initials R S, and the date, December 14, 1704 rests on a small, wooden platform inside the museum at St. Paul’s Church National Historic Site. The carving was crudely chiseled by the village blacksmith, and it is the oldest legible gravestone in the historic cemetery at St. Paul’s, one of the oldest in New York. Placed inside for preservation and display purposes, it is the gravestone of Richard Shute, whose remains are actually interred in the burial yard.

But who was he? Not anyone noted in a history book. But by exploring the life story of this man, we can almost look through the window into this early Westchester village. For in every new settlement, there are always a few of the most competent who stand out and hold the responsible offices, and so it was in the small colonial town first called The Ten Farms, and whose name quickly changed to Eastchester. One of these leaders was Richard Shute, whose public life would be influenced by his religious beliefs.

Born in 1640, he lived his early years in Fairfield, Connecticut, and already at the age of 24, was involved in the plans of his group of religious dissenters, or Puritans, to move to Eastchester. (It is interesting to note that Fairfield became troubled by delusions of witchcraft – even Shute’s uncle and aunt by marriage were accused, convicted, and presumably executed in 1662 ; but Eastchester was not to be touched by this scourge.) Here, they would form a covenanted village – each member pledged to each other; and governed by “Articles of Agreement” that they had themselves composed. There they would worship in a reformed church separate from the Church of England.

The trail of land ownership began in 1666 with the sale from Thomas Pell, Lord of the Manor of Pelham, to 10 men. Town records show that Richard Shute, at the age of 24, became owner and farmer of 41 acres of land that he named “Bicklye.” His property, along what is today South 3rd Avenue at the intersection of Columbus Avenue, was roughly similar to the other nine, for part of the group’s promise was to treat each other fairly and equally. Thus it, like the others, was divided into planting grounds, pastures for animals, and a lot for his home. Shute’s upland home lot of 10 acres was advantageously bounded on the south by the common and the roadway, on the west by the woods, on the north side by the wastelands and on the east by the King’s highway. But first, Shute’s primary concerns – as were the other men’s -- were housing and food. Most probably, he and the other settlers built basic dwellings and used the animals and other provisions they had brought. Living off the land, the new owners began planting and laying out fences to encircle the fields.

Shute’s village developed along similar lines to those in England and then Fairfield, with homes clustered around a village green. Farther out were to be wheat and corn fields and pastures for the horses, cattle, and sheep; nearby would be the school, fort, and mill. After obtaining a further land grant from the local Indians that were part of the Lenape tribe, Shute built his permanent house, the type that had originated in New England, and known as a “saltbox.” Consisting of a wooden frame building with a long, pitched roof sloping down low to the back with a central chimney, it had one story in the back, and two in front.

Richard Shute began his role as a leading citizen by the age of 36, when he was chosen to act as village representative to the governor, asking for permission to hire a minister, build the meetinghouse, or church, and be relieved from taxation to the established Church. But unlike modern times, wherein political office is largely equated with power and prestige, in the 18th century much was expected of a Puritan town leader. Social virtue was evidence of the faith that procured salvation, and this was expressed by public service. From the year 1676 almost to the year of his death, Shute was active in the affairs of this small rural society.

First in charge of land clearing and fencing, he also became surveyor, and took his turn as what we would today term farm animal health inspector and recorder. Shute also served as village Treasurer, Secretary, and Assessor. His longest office was that of Recorder, or Village Clerk -- in spite of his “horrible handwriting” and careless reporting that were noted. In this, one of the most important positions in the village since there was yet no mayoral office, he served from 1673 to 1703, just two years before his death. Toward the end of his lifetime, Richard Shute saw the beginning of the transition of St. Paul’s church to Anglicanism.

He died in 1704; there is no record of his eulogy. But like Ephraim Wood, a shoemakerfarmer of Concord, Mass., it could be said that, “In him were united those qualities and virtues, which formed a character at once amiable, useful, respectable, and religious. Early in life he engaged in civil and public business, and by a judicious and faithful discharge of duty acquired confidence, and reputation with his fellow citizens and the public…Having lived the life, he died the death of the righteous.” He lies now in the old section of the western side of the cemetery of Saint Paul’s; an image of his gravestone is included in the 18th-Century Stones section of the virtual cemetery tour available on this website.