Last updated: December 31, 2021

Article

Rev. Samuel Seabury: St. Paul's controversial minister of the era of the American Revolution

Rev. Samuel Seabury: St. Paul’s controversial minister of the era of the American Revolution

Samuel Seabury, a politically active and theologically conservative clergyman, served as the Anglican rector of St. Paul’s Church in the critical period on the eve of the American Revolution 1766-76.

Born in Connecticut in 1729, Seabury was the fourth and final Church of England minister who presided over the St. Paul’s parish through appointment by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG) in Foreign Parts, the missionary wing of the Anglican Church in the colonies. Honoring his oath to the King, a pivotal commitment of Anglican ministers, Seabury was a strident Loyalist, providing political and religious leadership to the Crown’s cause in New York, and was partially responsible for the sizable number of Tories in the St. Paul’s parish.Seabury followed his father, also named Samuel Seabury, into the church, and shared his commitment to the Anglican faith. The elder Samuel Seabury was trained as a Congregational minister at Yale University in New Haven, but upon graduation worked through the theological nuances of committing to the Church of England, and served as the Anglican rector at Hempstead, Long Island. Samuel Seabury the younger graduated from Yale in 1744, at age 15, and began reading prayers for an Anglican parish in Huntington, Long Island.

Sponsored by his father, Samuel Seabury in 1752 sailed to Edinburgh, Scotland to prepare for ordination as an Anglican clergyman. Like many churchmen, he also studied medicine in Scotland, and at various times in his life earned much of his livelihood as a physician. After consecration, Seabury returned to the colonies as an SPG minister, accepting a post in New Brunswick, New Jersey. A barrel-chested man, with a high forehead, broad nose and thin lips, Seabury married Mary Hicks, daughter of a wealthy Philadelphia businessman, in October 1756. They eventually had six children, one of whom, a son, Charles, followed his father’s calling as a clergyman.

In 1758, Rev. Seabury was appointed rector of the much larger parish of Jamaica, New York. A sprawling rural community, comprising all of today’s Queens County, it included churches in Jamaica, Flushing and Newtown, with many dissenters (non-Anglicans, usually Presbyterians) and Quakers. Church of England adherents in all three towns clamored for his attention, and he attempted the exhaustive challenge of weekly services at each. Seabury faced resistance to his high church practices, especially his emphasis on the sacraments. He quarreled with wealthy parishioners who were accustomed to broad influence over church affairs. Well publicized disputes with his father-in-law over debts on property didn’t help his image; Seabury was actually arrested on one occasion.

A transfer to the parish of lower Westchester County, which included churches at Westchester Square (today’s Bronx) and St. Paul’s in Eastchester, was a relief. At the Eastchester church, Seabury confronted lingering attachment to the dissenting Protestant religion of Presbyterianism, a local emergence of Deism, or freethinkers, and many residents who opposed any organized church. A particular problem even among his regular congregants was the reluctance to take the communion, or the Christian sacraments of the Lord’s Supper, which Seabury attributed to a fear of Divine punishment for false testimony about their beliefs, but also reflected deeper traditions of anti-Catholicism. Rev. Seabury arrived when the town had “just completed the roof of a large, well built stone church, on which they have expended, they say 700 pounds currency,” he noted in June 1767, referring to the extant edifice. The project had stalled because of funding shortages, and Seabury tried unsuccessfully to raise additional resources to complete the project.

Seabury seemed more secure, with extra earnings from a private school he administered supplementing his income raised through a tax on local residents to support the official church. Perhaps for that reason, he devoted less energy to local pastoral responsibilities and stepped onto a broader stage. He emerged as a leading Anglican clergyman in religiously diverse lower New York, where the Church of England was often under attack as an established religion which lacked broad support. Rev. Seabury articulated a strong position on the Episcopate controversy, or creating an Anglican Episcopal bishop in the colonies who could ordain ministers and relieve aspiring churchmen of the burden of travelling to Britain for sanctification. While the campaign for an American bishop failed, participation in public and religious arguments increased his proficiency in the pamphlet as a written form of political expression.

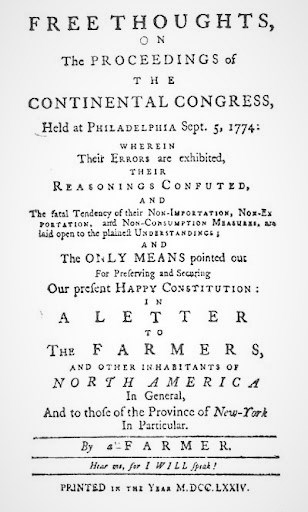

Seabury greatest historic significance was his critical role in 1774-75 in the emerging Loyalist cause in New York, and pamphlets now commonly called “Letters of a Westchester Farmer.” Spurred by boycotts and other restrictions approved by the First Continental Congress, Seabury’s “Farmer” essays -- anonymous, although his authorship was widely recognized -- emphasized a conservatism shaped by religion and tradition, warning about the dangers to life and property that followed an abandonment of vested authority for the uncertainty of a revolution and unknown leaders. These writings, part of a pamphlet competition with the young revolutionary Alexander Hamilton, made him notorious among Patriots, and led to his arrest by militia and brief imprisonment in New Haven, Connecticut in 1775.

Seabury also faced challenges and armed interventions from local Patriot militia over prayers for the King in the standard Anglican service. Beginning in April 1776, as New York prepared for a likely assault by British forces, Seabury’s presence in Westchester County became especially tenuous. His authorship of the “Letters” made him the target of insults and threats from American troops moving through the area to positions in the New York theatre of battle. County vigilance committees observed his movements. The British invasion of Brooklyn in August led to arrests of several Tories in the St. Paul’s area, who were perceived as a rear guard danger to the American army. With assistance from friendly parishioners, Seabury dramatically escaped on Sunday morning, Sept. 1, hurrying to a waiting boat beached near today’s Whitestone Bridge for a short trip through the East River. He immediately reported to the English commander General William Howe, declaring his loyalty to King George III.

Rev. Seabury’s clear support for the Crown and his knowledge of local roads and geography made him a valuable guide and source of information for General Howe during the British invasion of Westchester in October 1776. Seabury would have advised the British and later Loyalist commanders about the nearly completed St. Paul’s church as a potential hospital and military facility; the rector actually accompanied the English army at the Battle of White Plains. The war years were passed in New York City, with many other Loyalist refugees, including some parishioners, for whom he served as a source of comfort, if not support. Appointed by General Howe as chaplain at a Loyalist hospital in Manhattan, the rector also served as chaplain for a Loyalist regiment which included young men from Westchester; he earned additional income as a physician.

In 1783, as the Americans arrived in New York City in triumph, Seabury was preparing to join thousands of Loyalists in exile in Canada, when a chance encounter and discussion about the re-organization of the Anglican/Episcopal church led him to change plans. Connecticut Anglicans were concerned about religious continuity in wake of the Revolution, and needed to secure a Bishop for their state. Seabury, who was from Connecticut, emerged as the consensus choice. Supported by Episcopal clergy from the state, Seabury sailed for England seeking consecration.

Religious authorities in London denied his request, mostly because his American citizenship disqualified him from taking the required oath to the King. Additionally, English officials hesitated because the base of Seabury’s support was Connecticut’s Anglican clergy, not the state government, which did not recognize the Episcopalians as the official religion. He was more successful with the Scottish Episcopal Church, which had an independent, confrontational history with Church of England, and he was ordained at Aberdeen on Nov. 14, 1784, as the first American Episcopal bishop. Samuel Seabury died in 1795.