Last updated: December 15, 2023

Article

Rev. John Milner: The rector who started the building of St. Paul's Church

National Park Service

Rev. John Milner: The rector who started the building of St. Paul’s Church

Reverend John Milner played an important yet controversial role in the development of the colonial parish of St. Paul’s Church. As a recently installed priest, he welcomed the beginning of the construction of the stone and brick church still in existence. Only two years later, though, amid disputes and conflicting accusations, he left Westchester County for a church in Virginia.

The commencement of work on St. Paul’s Church in 1763 corresponded with a pattern of expansion and vigor under Rev. Milner’s aegis in a parish which had experienced a decline over the previous decade. Rev. Thomas Standard, Anglican (Church of England) rector of the parish of Westchester County, which included St. Paul’s, had been in poor health since the mid1740s, lacking the energy and mobility to effectively minister to the church. In the vacuum, the community experienced a notable decline in Church of England observances. Other denominations -- Deists, Quakers and independents (Presbyterians) -- claimed the spiritual allegiance of more residents, while many people shifted away from religious rituals entirely. Standard’s death at age 80 in 1760 prompted Church authorities to select a new rector for the parish located about 20 miles north of New York City.

Rev. Milner’s youth and background strongly recommended him for the position. He was only 23 at the time of his appointment, predisposed to supply the energy and innovation that had been lacking the previous decade. Born in New York in 1738, he was the first Anglican minister for Westchester County who was raised in the colony; previous rectors assigned to the parish by English religious authorities were born in Britain.

Milner graduated from the College of New Jersey (Princeton) in 1759, an institution designed to train Presbyterian clergymen. His choice of ordination as an Anglican pastor was probably inspired by Rev. Samuel Johnson, among the most influential Church of England ministers in the colonies and the first president of King’s College (Columbia) in New York. Rev. Johnson was apparently a family friend, although it is not clear why Milner didn’t attend King’s College.

Facing the common challenge of colonial churchmen, Milner in 1760 at his own expense sailed to England for ordination as an Anglican priest. Operating from London, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG) selected Church of England rectors for the American parishes. Because of travel distance, uncertain living conditions and inconsistent compensation, these colonial posts were difficult, unenviable assignments, and many Anglican churches in the colonies struggled to retain clergymen. SPG officials were relieved to identify a qualified, highly recommended churchmen and Milner was “promised to be ordained Priest on St. Matthew's day next, immediately after which he would be glad to return home, there being a ship now in the River to sail to New York." The Society agreed “to appoint him to the Mission of West Chester in the Province of New York now vacant by the death of Mr. Standard, for which he will receive a salary of 50 pounds per annum to commence from Christmas last."

After “a long and dangerous passage,” he arrived in New York in the spring of 1761 and, according to his reports, achieved rapid success. He informed London officials about preaching “to crowded audiences,” and confronted with alacrity the challenge of serving a multi- church, widely dispersed parish. Rev. Milner actually lived at Westchester, a town about five miles south of St. Paul’s, and was also responsible for churches in Yonkers, Pelham and New Rochelle, spanning an area of about 100 square miles.

The building of a large church in Yonkers, financed by wealthy landowner Frederick Phillipse, reflected the new energy of the parish, emerging from the economic disruptions and financial challenges of the French and Indian War. Rev. Milner reported little interference from dissenters, or non-Anglicans, citing “a few peaceable Quakers who have a meeting house at West Chester.” Later reports by the community leaders mentioned that even the Friends had started to attend his Church of England services. The measurable statistics of a pastor’s responsibilities were equally impressive, with the young priest citing healthy numbers of baptisms and communicants.

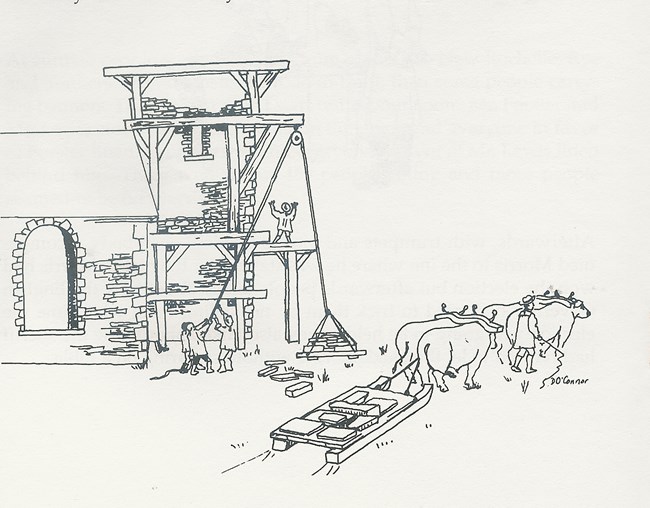

The beginning of the construction of the masonry church at Eastchester, the parish of St. Paul’s, corresponded with this series of developments heralding an expansion of formalized religion in Westchester County. Rev. Milner reported in 1764 that the town has started to build the new church replacing the “present edifice (which) is a mean wooden building erected in the infancy of their settlement,” a reference to the shingle building, measuring 28’ x 18’, placed about 60 yards west of the stone and brick edifice. With obvious pride, he reported in 1765 that the new edifice “will be covered this summer and when finished will make a beautiful appearance being all of stone in which it has the advantage of most country Churches in the province.”

The Westchester County churches, including St Paul’s, functioned as quasi-public agencies under the jurisdictions of the towns. In that context, Rev. Milner was not directly responsible for these projects in the sense that a minister today might solicit funds and assume a leading role in the construction of a new church. Yet, the developments clearly corresponded with a pattern of growth and expansion for the church. While Milner’s reports of greatly increased attendance at services and the yielding of dissenters to the Anglican persuasion were perhaps exaggerated -- the next Anglican rector of the parish, Rev. Samuel Seabury, also confronted a decline in religious observance -- he certainly stimulated new interest and devotion following the long period of decline under Rev. Standard.

What went wrong?

There are really two explanations for his departure from the Westchester churches. One of them involves a serious financial dispute between the minister and the community. At his own expense, Rev. Milner engineered extensive repairs to the parsonage house and built a new barn on church property in Westchester, where the vestry (a council of congregants which administered church affairs) promised to reimburse him “as soon as their circumstances which the late War and the present discouragement upon our trade have greatly impaired will permit,” a reference to the French and Indian War. The decline of religious affairs and the infirmity of Rev. Standard had reduced the maintenance of the church’s physical plant, and upgrades were probably necessary. The value of those repairs is difficult to determine. Rev. Milner indicated he would be satisfied with reimbursement of 100 pounds, or about half of total cost of his expenditure. Conversion rates of the value of money over the centuries depend on a variety of local and national factors, but it is accurate to say we would be talking about thousands of dollars in our contemporary currency.

Initially, the Westchester church leaders agreed to the re-imbursement “with great cheerfulness, as their minister’s (Milner) behavior has very much endeared him to the people.” But these pledges to cover Rev. Milner’s payments were subsequently withdrawn.

Beyond monetary concerns, another development may have influenced the church’s unwillingness to pay Rev. Milner, and contributed to his departure. Rev. Milner wrote in September 1765 that “my character has been traduced in such a manner that I can only indicate it among the few friends that know me best. I hope God who knows all things will deliver me from all my enemies.” In another correspondence with London church officials Rev. Milner claimed that there were “ungrateful as well as unjust aspersions thrown upon my character by a Secret enemy and which he had fixed in such a manner circumstances being altogether in his favor and I at his house that it was impossible for me in any court of justice to obtain the satisfaction that my injuries required.”

The accusations involved charges that Rev. Milner engaged in aggressive sexual advances towards young boys. Rather than face a formal inquiry, which could have led to dismissal from the ministry, Milner agreed to resign the Westchester post. Through informal Church networks in the colonies, Rev. Milner assumed pastoral duties at an Anglican church in Newport, Virginia, situated at the southeastern part of the province, in the county of Isle of Wright. Like many Church of England outposts, the Virginia church had difficulty securing ministers.

Through a lawyer, Milner attempted, unsuccessfully, to press the case against the Westchester vestry for compensation. Details of his ministry in Virginia reveal similar accusations of sexual advances towards young men, specifically mentioning sodomy, leading to his resignation in May 1770. He returned to New York City and lived in his family home. He remained in the city during the Revolutionary War, siding with the British and clearly identifying as a Loyalist. He returned to England after the American triumph in the war, and is believed to have died around 1790.