Last updated: May 17, 2021

Article

Restoration of Ed Galloway's Totem Pole Park

Article from the proceedings from Are We There Yet? Preserving Roadside Architecture and Attractions, April 10-12, 2018, Tulsa, Oklahoma. Watch a non-audio described version of the presentation on YouTube.

Grassroot Art Environments and Ed Galloway’s Totem Pole Park

Erin P. Turner, Ed Galloway Totem Pole Park Restoration Director, Social Practice Queens, Queens College, City University of New York

Abstract

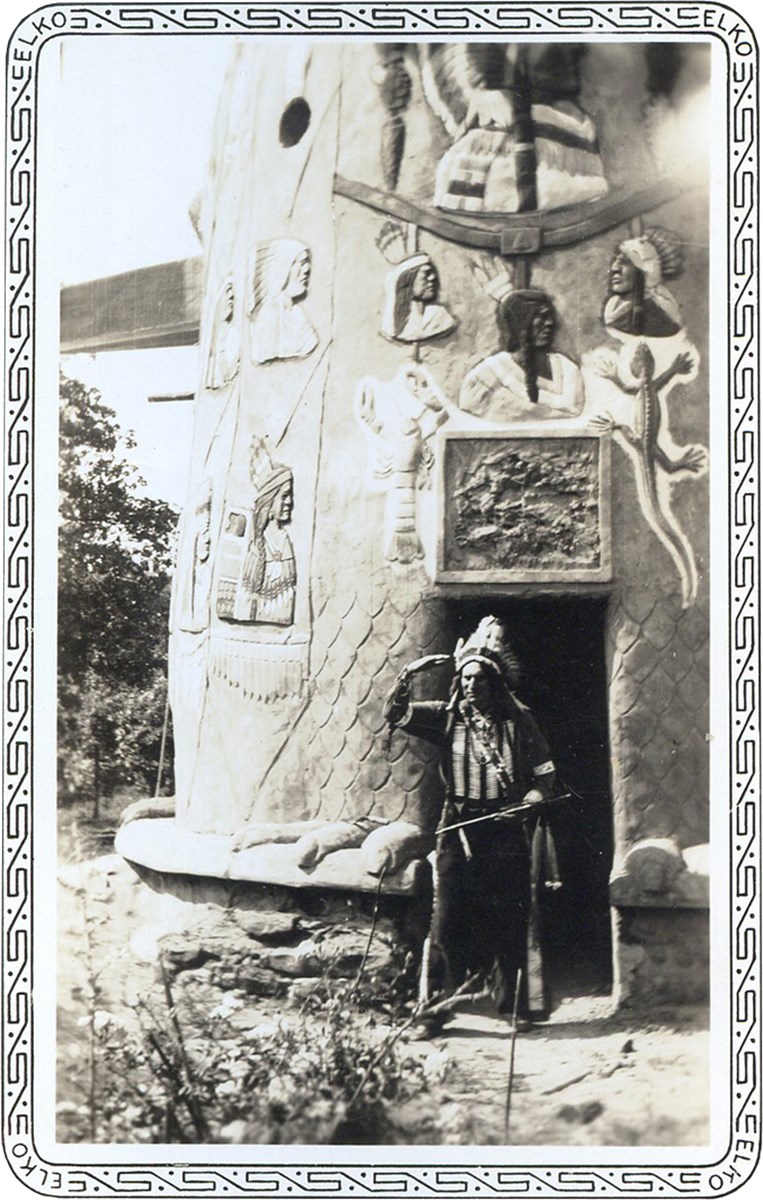

Located in Foyil, Oklahoma, just three miles east of historic U.S. Route 66, stands the largest concrete totem pole in the world measured at seventy-eight feet tall. Constructed between 1937 and 1948, it is estimated that twenty-eight tons of cement, one hundred tons of sand and rock, and six tons of steel comprise this structure. Most of the natural materials were collected from a nearby stream by Ed Galloway, the man behind this incredible sculpture. This large concrete totem rises from the back of an enormous turtle carved from an outcrop of sandstone, in tribute to Native Americans and Turtle Island, the indigenous term used for North America. The concrete totem features over two hundred hand-sculpted bas-relief creatures and Native American portraits, including four nine-foot tall Native American chiefs that stand near the top: Quannah Parker, Sitting Bull, Geronimo, and Chief Joseph. “All carved, and each one means something. Been offered a million but won’t sell. When he dies he will donate it … for a park.”1

This structure is one of fourteen other concrete sculptures that encompass the largest and oldest grassroots art environment in Oklahoma, including Galloway’s eleven-sided studio which now operates as the gift shop and museum. Due to its proximity to U.S. Route 66, Ed Galloway’s Totem Pole Park has become a popular tourist attraction, bringing in thousands of visitors a year from all over the world.

After Galloway’s death in 1962, the Totem Pole Park fell into disrepair. In 1982, the Kansas Grassroots Art Association initiated a restoration project that would take over sixteen years to complete. In 1999 Ed Galloway’s Totem Pole Park became recognized in the National Register of Historic Places.

In 2014 the Totem Pole Park had once again succumbed to severe weathering and bleaching of the painted surfaces. Another restoration project began, spearheaded by David and Patsy Anderson, directors of the Totem Pole Park, Erin Turner, Margo Hoover, and the Rogers County Historical Society. The team has completed two phases of restoration on the large totem. This presentation will discuss grassroots art environments, new preservation standards for concrete structures, and the future restoration phases of the Ed Galloway Totem Pole Park.

“All my life I did the best I knew… I built these things by the side of the road to be a friend to you.” -Ed Galloway

Ed Galloway Totem Pole Park archives

Grassroots Art Environments

Those works created from solitude and from pure and authentic creative impulses - where the worries of competition, acclaim and social promotion do not interfere - are, because of these very facts, more precious than the productions of professionals. After a certain familiarity with these flourishing of an exalted feverishness, lived so fully and so intensely by their authors, we cannot avoid the feeling that in relation to these works, cultural art in its entirety appears to be the game of a futile society, a fallacious part.[2]

Art Brut, folk art, outsider art, intuitive art, marginal art, naive art, neuve invention, visionary environment, grassroots art environment. All of these terms relate to artistic creations that lie outside of the margins of the art world [3] and its academic and market structure. More specifically, these artists are not formally trained in art, therefore do not utilize the same conventions of art, design, or media as an academicized artist would.

Grassroots art environments or visionary environments are collections of “immobile constructions or decorative assemblages” [4] created by self-taught artists and/or craftsman made from a variety of surplus materials that are easily found or collected. These environments are found all over the world in a variety of shapes, sizes, and materials, often built to a monumental scale. The visionaries behind such art environments are oftentimes solitary humans on the fringes of society creating transformative environmental works that speak to a reality of the marginalized human experience. In the American context, the visionary voices behind grassroots art environments includes the mentally ill, “immigrants, African Americans, the poor, women, homosexuals, elderly, and born-again Christians”[5].

Although these works encompass a multitude of perspectives, there are trends within this genre to understand the importance of their function in our society, and about a history that is oftentimes ignored. Measures to preserve these creations fortify the history of multiple dimensions of the American experience. However, due to the unconventional attributes, atypical locations, and the immobile nature of grassroots art environments, preservation is challenging for a variety of reasons. These include funding, public perception, and understanding the historic context of such sites.

I will focus on one such art environment, the Ed Galloway Totem Pole Park, found three miles east of historic Route 66 in Foyil, Oklahoma. Built between 1937 and 1962, it is the vision of its namesake and includes a variety of large and small concrete structures that were hand built and carved with bas-relief embellishments depicting animals, creatures, and Native American portraits. This site is the creation of a poor American man from rural Missouri and Oklahoma whose sculptural work monumentalized both Native Americans and the natural world. Born in 1880, he offers us an interesting point of view, one that saw the shift in social history from Indian Territory to Oklahoma statehood, and who clearly understood the importance of celebrating those cultures who were on this land first.

Ed Galloway’s Early Works

Ed Galloway was a craftsman and artist from a very young age, carving small items such as boxes and buttons out of wood and shell. After serving two years in the Philippine-American War, being discharged in May 1904, he swiftly began making larger carvings. “I spent several months working for the government in Japan and in the Philippine Islands where I became interested in Japanese art. In studying the wood carvings, I decided to try my hand at the art.” [6] The influence of Eastern art is apparent in Galloway’s woodwork, utilizing finely detailed relief and inlay. It was in rural Missouri and Oklahoma where he began to gather the wood for his carvings, which ranged in size from small boxes and figurines to figurative sculptures over twelve-feet tall. He carved ornate fiddles, many of which did not produce sound but functioned solely as the vehicle for the inlaid figure and exotic wood samples he collected from all over the world. Although many of his creatures and designs reference local flora, fauna, and scenes from the heart of the United States, tropical insects and animals, which he would have seen during his enlistment in the Philippines, are also interspersed. These figurative works show his lived world transformed into visual creations.

Ed Galloway Totem Pole Park archives

Galloway’s interest in woodworking developed into a long teaching career. For over twenty years he taught manual arts and woodworking to orphaned boys at the Sand Springs Home, just west of Tulsa. Although he made only a meager wage, he was devoted to helping those who had less means than himself. This perspective was not only his way of life but would also became the mission of the Ed Galloway Totem Pole Park.

Shifts in Material

After Galloway’s retirement at the Sand Springs Home in 1937, he began to utilize concrete as a material for his art objects. Concrete had become popular in the first two decades of the twentieth century and was both widely available and cheap, due to the opening of many Portland cement factories across the United States. The neighboring state of Kansas became the fourth largest producer of Portland cement in North America. Throughout the Midwest, there was an ample supply of the minerals necessary to make cement: limestone and shale. Natural gas fueled production of which Kansas and Oklahoma had an abundant supply. Concrete was shipped from the plants via railway, and widely distributed.[8] Concrete is durable, weather-proof, and enables large-scale construction in a short amount of time. From the increased availability of this material came a rise in concrete art environments.

The Midwest region of the United States saw a number of art environments pop up following the popularization of concrete as a new material. S.P. Dinsmoor’s Garden of Eden in Lucas, Kansas was built between 1907 and 1928 and is comparable in scale to the Ed Galloway Totem Pole Park, however it is unclear if Galloway would have known about this art environment. [He did, however, travel through the Pacific Northwest, and would quite possibly have seen totem poles in their native environment, or perhaps through the photographs found in National Geographic, which he used as reference material.] Perhaps his studio fire influenced the shift in his material choice for the larger public art environment, as he realized the necessity for an indestructible material.

A Monument to Native Americans

Ed and his wife, Villie, bought a parcel of land near Foyil, Oklahoma in the early 1920s. There, Ed slowly built a small stone house where he and Villie would live for the remainder of their lives, post-retirement. After building their home, he began constructing a turtle body from a large outcropping of sandstone near his home. On the back of this turtle he would spend the next eleven years building a seventy-two-foot tall totem pole, all in bas-relief, adorned with over two hundred fastidiously hand-carved animals, creatures, and portraits of Native Americans. At the pinnacle of the totem stand four nine-foot-tall, full-figure Native American chiefs.

Looking into the rising sun is the peacemaker, Chief Joseph, a Nez Perce; ominously watching the setting sun is the stalwart Apache warrior, Geronimo; gazing severely, yet serenely, to the northward is the champion of the historic Battle of Little Big Horn, Sitting Bull, Chief of the Sioux; the grave, intelligent man with the winning personality, Chief of the Comanche, Quanah [Parker], the Eagle, scans the horizon into the Lone Star state and all the southland.[9]

Ed Galloway Totem Pole Park archives

The Totem Pole Park is a monument to Native Americans and the natural world. Although totems are traditionally produced by tribes along the Northwest Coast of the United States and Canada.[10]Ed Galloway took care to include a wide variety of significant Native American figures and tribes, represented figuratively, symbolically, and architecturally throughout the park. The large arrowhead is flanked on one side by Oklahoma’s five ‘civilized’ tribes, the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole, and on the opposite, Western tribes. Important figures from four distinct plains tribes (Nez Perce, Apache, Sioux, and Comanche) look out from the top of the large totem.[11] Representations of the Omaha, Kickapoo, and Mandan tribes have been identified as well.12

The Fiddle House, sitting to the east of the large totem, is an eleven-sided building inspired by the Navajo hogan. This structure acted as a workshop, studio, and exhibition space open to people visiting the Totem Pole Park. Over four hundred fiddles and other pieces created by Galloway with inlaid carvings were on display. Preceding Galloway’s death, the park slowly fell into neglect and several hundred fiddles were stolen. Presently, 135 fiddles hang on display in the Fiddle House.

As the iconic U.S. Route 66 became an attraction in the 1950’s, different businesses and curiosities popped up along the famed highway. Galloway saw an opportunity to share his park with passersby and placed signs along the highway directing them towards the Totem Pole Park. A number of newspaper articles about his creation brought local visitors, while Route 66 attracted people from all over the world. Ed wanted to provide a place of wonder and intrigue, a place where people could come and appreciate the monuments to Native Americans and pay reverence to those who came before us.

Galloway built picnic tables and a barbeque grill so that people would stay and utilize the park. From the beginning of its existence, the park has been free and open to the public 365 days a year.

Kansas Grassroots Arts Association and Other Restoration Initiatives, 1982-2009

After Ed Galloway’s death in 1962, his surviving son and daughter-in-law, Paul and Joy Galloway, found the park difficult to maintain. The park became overgrown with weeds and the sun bleached the paint, which soon started to chip and peel off the concrete. In the early 1980s, the Kansas Grassroots Arts Association (KGAA) became interested in the totem and began the long process of restoration and preservation. The group, based in Lawrence, Kansas, reviewed piles of old photographs to determine how the totem was once painted, because the paint was severely weathered. They conversed with local residents about the brilliance of the colors and memories of Ed Galloway’s construction. They analyzed paint chips and matched these chips to the paint colors found on the interior of the Fiddle House, as these murals had survived with far less damage than their exterior counterparts. They worked with local paint companies that had been in operation when Galloway was painting his structures, and identified eighteen colors that where popular during that period: “brick reds, aquamarines, dark green, bright pinks, chartreuse, and yellows.”[13] They were committed to get as close as possible to the original materials and paint colors used by Ed Galloway. This proved difficult, as Galloway had repainted the surface of the totem several times, when previous colors faded due to sun exposure. He was known to collect old paint cans from anyone that would donate materials and supplies and was repainting the totem up until the day that he died.[14]

The KGAA chose the color of the top layer of the paint chips that they recovered from the structures. “The final coat of paint appeared to be less detailed than earlier layers. A spotted bird with detailed toenails might, at a later date, have been given a single coat of paint. Although the top coat was followed for color, the details were added based on the photographs and relief of the sculpted surface.”[15] Instead of using a lead-based paint, like that which Ed Galloway would have used, they switched to a modern acrylic paint, based on consultations with conservators.[16]

The work that the KGAA did to recover the paint scheme is irreplaceable and is the only compiled record of what is considered to be the original color palette. Hand-drawn diagrams indicated the color codes of each of the figures in a paint-by-number graphic that was used by the volunteer painters for accuracy. The surface of the structure was scrapped with wire brushes to remove the existing paint chips. Exposed metal and rust was cleaned and covered. Holes were caulked with a high-grade silicone acrylic sealer.[17]

This volunteer restoration project spearheaded by the KGAA took over sixteen years to complete, including research, fundraising, stabilization, and restoration. The Rogers County Historical Society (RCHS) purchased the property and eventually took ownership of the Totem Pole Park in 1992, in collaboration with KGAA and Joy Galloway. In 1999, after two previous rejections, the Ed Galloway Totem Pole Park was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

In 2009, the totem needed to be repainted. RCHS had received a grant in the amount of $3500 from Questers, and Virginia Krugloff began to repaint the lower third of the totem pole using again, acrylic latex paints.[18] It was during this restoration that David and Patsy Anderson became involved in the project. They became the new directors of the Totem Pole Park, replacing Carolyn Comfort after a sixteen-year-term as the RCHS project director.

Present Restoration Project, 2014-Present

While Virginia Krugloff had repainted the lower third of the large totem, this still left over 50 feet badly in need of a facelift. In 2014, a new conservation effort began, spearheaded by artists Erin Turner and Margo Hoover, and overseen by Directors of the Totem Pole Park, Patsy and David Anderson and the Rogers County Historical Society (RCHS). The team researched the standards of historic preservation on large concrete totem poles. Due to the unique nature of such structures, following standards for conservation resulted in a variety of interesting resources and procedures.

The KGAA passed down their original color palette and extensive analysis of the site. This information has been invaluable, and it is the current restoration team’s main goal to follow this color scheme as closely as possible.

SPACES: Saving and Preserving Arts and Cultural Environments

Recent restoration has benefited from association with SPACES, a nonprofit public organization created with an international focus on the study, documentation, and preservation of art environments and self-taught artistic activity.”[19] SPACES founder, Seymour Rosen, was instrumental in introducing grassroots art environments as a genre to the world. His life was dedicated to the documentation of art environments and he visited the Totem Pole Park in 1981 to photograph the then weathered and decrepit structures.[20] Rosen’s twenty-two thousand photographs initiated the SPACES online archives, which is now recognized as the most extensive archive of art environments.[21]

Although not alone, he truly can be credited as one of the very few people who defined and clarified an entire genre of art. He celebrated the idiosyncrasy and the obsession, the boundary-breaking, paradigm-ignoring, wonderful excesses of these artists, and through this he has indubitably—and perpetually—changed our cultural landscape.[22]

The SPACES archive presently provides information on over twelve hundred art environments located all over the world. Part of the recent restoration efforts has included growing the online archive of the Totem Pole Park, including digitizing all photographs, preservation diagrams, and other pertinent information and contributing these images and documents to SPACES online archive. Contributing this information to the public domain may promote future conservation acts and provide greater protection for the Totem Pole Park.

SPACES also provide extensive resources for preservation of concrete art structures. Researchers were put in contact with Keim Mineral Coatings, a company that specializes in silicate-based paint.[23] These mineral based paints petrify into the concrete substrate through a natural chemical bond. The paint is environmentally safe, anti-static (keeping the surface clean, as dirt cannot cling), lightfast (color is unaffected by UV rays and will not fade), water vapor permeable (allowing the surface to breath), non-film-forming (surface will not peel), water repellent, does not contain solvents and plasticizers, and algae and fungi resistant. This paint lasts more than double the length of time that latex would last under the same circumstances. The variety of silicate-based paint colors available is limited, due to the constraints of mineral colors, however, new paint colors were able to be closely match the latex colors through a thorough selection process.

To date, two phases of the restoration of the large totem have been completed, which includes the top two-thirds of the structure. The surface was cleaned down to the concrete substrate using a low-pressure power wash, working in small sections so that the concrete would not be left bare for extended periods of time. In areas where exposed metal was found, the metal was cleaned and coated with a rust converter. In areas where there was damaged concrete, it was patched and repaired.

Erin P. Turner

This restoration project has been supported through small fundraisers including local asks, the annual Totem Pole Barbeque and Music Festival, a Kickstarter campaign, and donations made to the Totem Pole Park through the gift shop. Fundraising for the next phases of restoration are underway, which includes completing the restoration of the large totem, the remaining concrete structures in the park, and the Fiddle House.

A Closer Look at Our Restoration Goals

Phase Three

The next phase of the project is to remove the latex paint from the lower twenty-five feet of the large totem and replace it with the silicate-based paint. The majority of this work will need to be done on a small lift for ease of accessing the higher parts of this level. It is important to complete this phase as soon as possible so that the age of the paint is consistent throughout the entire structure. Completing the last phase of large totem restoration will take about six weeks.

David Anderson

Phase Four

The goal of this phase is to replace the latex paint from the rest of the smaller structures in the park. These include the small bird totems, two totem gates, a bird bath, a large concrete tree, a large arrowhead, fireplace and barbeque, two picnic tables and chairs, two large bird totems, and the exterior of the Fiddle House.

It’s hoped community members will be involved in this phase by providing hands-on support. A goal is to partner with a local university and offer a class on grassroots art environment restoration. They would learn preservation methods and standards, and aid in the removal of the paint and then in repainting the structures. The class could build community involvement to protect regional treasures and to help secure the future of the Totem Pole Park.The class would educate on not only the Totem Pole Park, but about the relevance and importance of other grassroots art environments. A common consensus is that by promoting a national context for art environments, this will help in the evaluation and preservation of many other visionary art environments.[24]

Margo Hoover

Phase Five

This phase focus on the interior of the Fiddle House. Wooden art objects, old photographs, the remaining fiddles, and other displays from Ed Galloway’s life are currently exhibited in the house. Project goals are to stabilize the archival prints, design a better display for the ‘museum,’ create an educational component available for visitors and school groups, and digitize all information available on the park and the preservation process.Another goal is to continue Galloway’s commitment to the education of children by working with educators to develop curriculum focused on cultural history and creative activities. Through this outreach, it’s hoped that more schools and organizations will utilize the park. The proposed curriculum will uphold both the Oklahoma Academic Standards, as well as build context of the local grassroots art history. Also, under development is a walking tour for visitors. As part of the educational mission, the Fiddle house could possibly serve as a small library focused on visionary art environments, Oklahoma history, and Native American tribes. This would not only give context to the Totem Pole Park, but also create a resource for those interested in the preservation of similar sites.

Included in this last phase is a digital, open access web source to house all pertinent information on the Totem Pole Park and the restoration process. Making the resources available for future generations will further protect and promote the survival of this amazing visionary environment. Project information will not only be contributed to SPACES but will also push other digital content within the in the public domain.

the Ed Galloway Totem Pole Park archives

Ed Galloway Totem Pole Park archives

Conclusion

This project has been committed to furthering not only the mission of Ed Galloway, but also Seymour Rosen and SPACES, the KGAA, Carolyn Comfort, Virginia Krugloff, John Wooley, and David and Patsy Anderson. Each of these people, or groups, has shown considerable commitment to the protection and preservation of the Totem Pole Park. Without the commitment of the KGAA to arts environments, and the acquisition by RCHS, the work would be far more difficult. The future of the park is also more secure because it is owned by an historical society committed to its preservation.

Ed Galloway built his park to be free and open to the public year-round so that everyone could enjoy his creations in nature. He was not only committed to the education of all children, especially those who experienced adversity, but also to the education and monumentalization of all Native American tribes. A project goal is to establish more relationships with Native American artisans and to sell their handiwork in the Fiddle House. Another goal is to continue to educate visitors not only on the history of Native Americans, but also the vibrant present and future of these tribes, and their role in Oklahoma and the nation.

Finally, the project seeks to promote more pride and understanding of the importance of visionary art environments and to make the Totem Pole Park a site for education not only about Ed Galloway’s life and art, but also on the genre and importance of these sites as American treasures and non-institutionalized art practices.

Endnotes

- Unidentified handwritten text found on the back of an old photograph of the totem pole, courtesy of the Totem Pole Park archive.

- Jean Dubuffet, “Place à l’incivisme” (Make Way for Incivism), Art and Text, No. 27, December 1987-February 1988: 36.

- These genres include marginalized persons, noninstitutionalized artists, and/or artists who exist outside of the art market. This, however, is starting to change as these artists are increasingly making their way into the market in such ways as the Outsider Art Fair.

- “What is an Art Environment,” SPACES: Saving and Preserving Arts and Cultural Environments, accessed March 11, 2018. http://spacesarchives.org/about/what-is-an-art-environment/.

- Keith S. Hébert, “The Psychedelic Assisi in the Southern Pines: Pasaquan, Visionary-Art Environments, and the Na-tional Register of Historic Places” In: World Heritage and National Registers: Stewardship in Perspective, edited by Thomas Gensheimer and Celeste Lovette Guichard (New York: Routledge), 37.

- Opal Bennefield Clark, A Fool’s Enterprise: The Life of Charles Page (Sand Springs, Oklahoma: Dexter Pub. Co., 2001), quoted in John Wooley, Ed Galloway’s Totem Pole Park (Claremore, Oklahoma: Rogers County Historical Society, 2014), 14.

- From 1910 to 1914, Galloway prepared sculptures for exhibition at the Panama Pacific International Exhibition in San Francisco. Around 1913, a fire broke out down the hall from Galloway’s studio. Reportedly, he ran into the burning studio to save his work, but only managed to push this one sculpture from the window, rescuing it from the flames. It rolled down the street and still has gravel imprints from the tumble. John Wooley, Ed Galloway’s Totem Pole Park (Claremore, Oklahoma: Rogers County Historical Society, 2014), 18.

- Cathy Dwigans and Ray Wilbur, “Survival of Grassroots-Art Environments” In: Backyard Visionaries: Grass-roots Art in the Midwest, edited by Barbara Brackman and Cathy Dwigans (Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 1999), 127.

- Joe Zodrow, “Smoke Signals,” Claremore Daily Progress (Claremore, Oklahoma), November 6, 1960, quoted in John Wooley, Ed Galloway’s Totem Pole Park (Claremore, Okla-homa: Rogers County Historical Society, 2014), 38.

- Wright, Robin K. (n.d.), “Totem Poles: Heraldic Columns of the Northwest Coast,” University of Washington, University Libraries, American Indians of the Pacific Northwest Collection, accessed March 11, 2018. https://content.lib. washington.edu/aipnw/wright.html.

- John Wooley, Ed Galloway’s Totem Pole Park (Claremore, Oklahoma: Rogers County Historical Society, 2014), 44.

- Barbara Brackman, “Ed Galloway’s Totem Pole: A Case Study in Restoration” In: Backyard Visionaries: Grassroots Art in the Midwest, edited by Barbara Brackman and Cathy Dwigans (Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 1999), 102-103.

- Ibid., 105-107.

- John Wooley, Ed Galloway’s Totem Pole Park (Claremore, Oklahoma: Rogers County Historical Society, 2014), 47.

- Barbara Brackman, “Ed Galloway’s Totem Pole: A Case Study in Restoration” In: Backyard Visionaries: Grassroots Art in the Midwest, edited by Barbara Brackman and Cathy Dwigans (Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 1999), 105.

- Ibid., 106.

- Ibid., 106.

- John Wooley, Ed Galloway’s Totem Pole Park (Claremore, Oklahoma: Rogers County Historical Society, 2014), 71.

- “What is SPACES,” SPACES: Saving and Preserving Arts and Cultural Environments, accessed March 11, 2018. http:// spacesarchives.org/about/what-is-an-art-environment/.

- His photographs show the Fiddle House at that time with major roof damage, exposing the interior murals to the same plight as the exterior painted structures: the inclement weather of Oklahoma. “Ed Galloway Totem Pole Park,” SPACES: Saving and Preserving Arts and Cultural Environments, accessed March 11, 2018. http://spacesarchives.org/explore/collection/environment/totem-pole-park/.

- Jo Farb Hernandez. “Seymour Rosen Biography,” accessed March 11, 2018. http://spacesarchives.org/about/seymour-rosen/seymour-rosen-bio/.

- Ibid.

- Although there are many silicate paint companies it was determined that Keim had the largest color range in their product, obviously important for the eighteen-color com-position found in the park.

- Keith S. Hébert, “The Psychedelic Assisi in the Southern Pines: Pasaquan, Visionary-Art Environments, and the Na-tional Register of Historic Places” In: World Heritage and National Registers: Stewardship in Perspective, edited by Thomas Gensheimer and Celeste Lovette Guichard (New York: Routledge), 36.