Last updated: February 19, 2021

Article

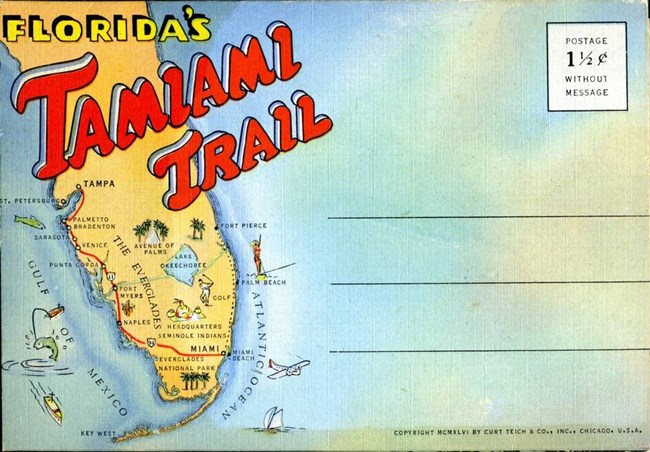

Removing the cork in the bottle: Reconstructing Tamiami Trail to restore water flow to Everglades National Park

Photo courtesy of Collier County Museum

It’s April 26, 1928, and the two-lane Tamiami Trail is finally complete. For the first time ever, people can travel easily by car from Tampa to Miami, hence the name Tamiami.

How did engineers get it done? Time, money and explosives.

Also known as U.S. Highway 41, Tamiami Trail was considered a feat of engineering at the time. It took over 11 years and cost $7 million to complete the 264-mile roadway. The builders used approximately 3 million sticks of dynamite in Collier County alone to create the canal adjacent to the highway and to provide the dirt fill to construct the roadway.

The road was great for the economy of Southwest Florida and allowed this part of Florida to become a center for real estate, business, and tourism.

It was disastrous for the Everglades ecosystem.

Photo courtesy of Tim Long.

The negative effects on the Everglades ecosystem were recognized early. Beginning in the 1940s, a series of bridges, culverts, and conveyance structures were added to help prevent flooding and improve water flow.

These weren’t complete fixes, and the eastern 10.7-miles, located between the L-31N and L-67 Extension levees, still greatly limited the amount of water that could flow into Northeastern Shark River Slough.

This part of Tamiami Trail was so low that it was impossible to raise water levels high enough in the adjacent L-29 canal to allow water to flow into the park without it flooding and damaging the road.

Water levels continued to drop south of the road. Because it was now drier than it should be, there were more wildfires and there were more exotic plants. The ecosystem continued to decline.

But there’s a happy ending to this story.

Starting in 1989, with follow-up efforts in 2009, Congress authorized a comprehensive plan that, although costly, aimed to finally fix the water flow problem created by the Tamiami Trail. The connection between southeastern and southwestern Florida would remain.

NPS photo

They lined up each bridge with historic sloughs, or low-lying areas naturally found in the Everglades, to allow the maximum amount of flow under them and to get the water further south as quickly and easily as possible.

They cut costs and gave drivers a glimpse into the Everglades by “super elevating” the north side of the bridge. This allowed them to spend less money on drainage structures since the road now sloped downward, and it gave many people their first, and perhaps only, window into the River of Grass as they drove by.

NPS photo

The project was only midway complete when they realized they didn’t need more flow, but instead the water needed to be distributed across the Everglades better.

“We did an analysis of the flow under the bridges and found that adding more bridging didn’t increase water flow that much more,” said Charles Borders, who was the National Park Service lead and former project manager on the Tamiami Trail Next Steps Project. “For about half of the money, we could add in culverts which would solve the distribution problem as well.”

With those surprise findings, they changed course and instead of adding more bridges, they started to plan where to add in more cost-friendly culverts, or tunnels that allow water to flow under the Trail.

The remaining 6.7-miles of the eastern Tamiami Trail will be reconstructed with additional culverts, in historic sloughs when possible, and with more structures for roadway safety and stormwater treatment. The entire project will finally be completed by 2024.

We are already seeing some promising results as water is now flowing more freely. This year we’ve seen high water levels throughout the park, definitely helped by high rainfall, but undoubtedly also facilitated by the completion of the bridges on the Tamiami Trail.

NPS figure by Amy Renshaw

Engineers may have made a mistake with the first road, but they’ve fixed it. The metaphorical cork in the Everglades bottle is out: Bring on the water!