Last updated: January 12, 2022

Article

Religion in the Wilderness: the Early Years of the St. Paul's parish

Religion in the Wilderness: The early years of the St. Paul’s parish

The early history of the parish of St. Paul’s, from the 1660s through the early 1700s, chronicles a struggle to sustain religious practices in a small community lacking the resources and legal standing to function effectively as a church.

Founded in 1664, the church community correlated directly with the town of Eastchester, a common arrangement when religion was valued as the moral underpinning of civic relations. The original English settlers were Puritans, opposed to the established (Anglican) Church of England. Because of that denominational profile, they experienced continuous difficulties gaining recognition as an official parish from New York’s colonial authorities. The town operated the church on an independent basis, and retained the services of ministers who followed the community’s religious preferences, Presbyterians or Congregationalists.

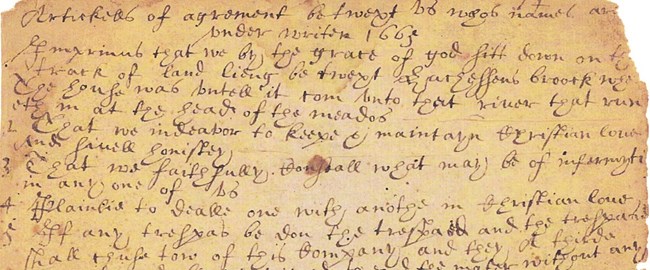

A covenant among the original families implores “that we indeavor (endeavor) to keepe (keep) & maintain Christian love and sivell (civil) honesty” and that we “plainlie (plan) to dealle (deal) one with another in Christian love.” Another article of the covenant instructs “That we give some encouragement to Mr. Brewster eatch (each) other weeke (week) to give us a word of exhortation and that when we are settelled (settled) we mete (meet) togeather (together) etch (each) other weeke (week) one hour to talke (talk) of the best things.” This remarkable document reveals a respect for religion as the organizing principle of moral communal behavior and a goal of conducting formal services on a bi monthly basis. Those themes established the patterns of the community’s early ecclesiastical history.

Through a coincidence of historical timing, the original conception of the settlement as an outpost of English civilization in the Dutch colony of New Netherland was immediately altered by the inclusion of the town into the British colony of New York. This shift in jurisdiction followed the English defeat of the Dutch months after Eastchester was established. While the settlement in Westchester County gained protection and legal advantages through incorporation into a British colony, the transition derailed a strategy to establish a separate parish. Following the English takeover of the province, the town was subjected to the directions of Royal Governors who hesitated to sanction a church of dissenters, or non-Anglicans. Colonial officials also insisted on recognizing the small Eastchester settlement as part of the nearby parish at Westchester Square, about five miles away. Citing difficulties traveling to the other church and a preference to select their ministers, town leaders resisted this arrangement and preferred to operate their own parish.

The refusal of New York’s Crown-appointed officers to recognize an Eastchester parish prohibited the town from raising public revenue for ecclesiastical purposes. This ban prevented the collection of taxes for construction of a house of worship; instead, services were conducted in the larger, more centrally located homes. In addition, the town faced legal obstacles in utilizing public funds to compensate the ministers, and often relied on voluntary contributions by local residents. In 1692, for instance, Samuel Godding, who led Sabbath services, received one bushel of “good winter wheat” from Henry Fowler and “five pecks of Indian Corn” from John Pinckney.

The description of the town’s religious origins presented here could create an impression of an irregular, isolated church, following uncommon beliefs and resisting organization, but that characterization would be misleading. Early Eastchester residents worshipped in conformity with established Puritan religious views, and selected well educated, ordained clergymen through normal channels; several of them were graduates of Harvard University, created as a training ground for Puritan clergymen. Most of the pastors were young men beginning callings as clergymen in the colonies.

Town's First Minister

The profile of Nathaniel Brewster, the town’s first minister, set the pattern for the subsequent clergymen serving the community through the 17th century. Born in 1620, Brewster’s father was a Mayflower passenger from England, and Nathaniel was among the first graduates of Harvard University, created to train ministers who dissented from official Anglican doctrines. Brewster lived in Setauket, on Long Island, and was a relative of Thomas Pell, an English colonist who in the 1650s secured land in today’s Bronx and Westchester Counties. In 1664, Pell sold a portion of his holdings to the original Eastchester settlers; he recommended Brewster as a minister. On a rotating, or itinerant basis, Rev. Brewster visited scattered communities in the area, including the parish of St. Paul’s, to perform divine services.

When Rev. Brewster -- or any of the subsequent ministers -- could not reach Eastchester, townsmen led prayers for the community. A surviving record notes that in 1677 Philip Pinckney, a prominent citizen, presided at a religious service. The format of non-ministerial services can be appreciated through this description of a mid-17th century Westchester County religious meeting by a Dutch traveler:

"After dinner, Cornelius Van Ruyen went to the house where they held their Sunday meeting, to see their mode of worship, as they had as yet no preacher. There I found a gathering of 15 men, and ten or twelve women. Mr. Baly said the prayers, after which, our Robert Bassett read from a printed book a sermon, composed by an English clergyman in England. After the reading, Mr. Baly gave out another prayer and sang a psalm, and they all separated."

The community-organized service acted as an acceptable, temporary measure. Yet, it seems clear from local records that the town preferred to retain a regular minister who would conduct a formal Puritan observance, which usually consisted of a Bible reading, a lengthy sermon, singing select Psalms, and some prayers. Minutes of meetings and other sources document strategies for retaining a minister, and they usually register a compensation package of some kind.

In 1677, town records show “that if it Bee the Will of God to Bring a minister to Settle Amongst us we have engaged to pay him forty pounds a year for his subsistence. Also to provide him a house and land for his uses during the tim (time) he staiteth (stayed) here as our minister.” Also in the 1670s, the town offered an annual salary of the equivalent of 40 pounds in farm produce and a house in a campaign to encourage Rev. Ezekiel Fogge, a dissenting minister born in England, to serve as their resident minister. A similar offer was tendered to Rev. Morgan Jones, who preached to a congregation in Newtown, today part of the borough of Queens in New York City. In 1684, Eastchester, along with the neighboring towns of Westchester and Yonkers, “do accept of Mr. Warham Mather (a Harvard graduate) as our ministers for one whole year, and that he shall have sixty pounds, in country produce, at money price, for his salary, and that he shall be paid every quarter.”

These proposals indicate a goal of retaining a consistent minister, following the pattern of most Puritan communities in New England, but in New York these initiatives were problematic. While the town voted to allocate funds and extend invitations to clergymen, the Royal Governor could invalidate these ordinances using public funds to compensate a non-Anglican minister. This constant concern of nullification of local ecclesiastical laws qualified the stability of the church.

Religious conflict between the town and the colonial government

The Ministry Law of 1693 in New York and the founding in 1701 of the Anglican Church’s missionary wing, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, had an important effect on religious affairs in the town. The 1693 legislation created six publicly supported parishes in southern New York, including Westchester County, and called for “a good sufficient Protestant Minister, to officiate, and have the care of souls,” in each district. Optimistically, the parish of St. Paul’s interpreted the law to mean that their preferred independent clergymen could gain recognition as the official minister. After years of unsuccessful efforts, town leaders utilized the new law to gain permission to build a meetinghouse, an emerging necessity for a town whose population was approaching 200. Completed in 1700, the wooden shingle building measuring 28 ‘x 18’ was situated about 60 yards north of the extant stone St. Paul’s Church.

Colonial officials countenanced the request to use local tax revenue to build the meetinghouse, but they had a different understanding of an official minister who would preside in the rectangular edifice. Part of a strategy to firmly establish the English church in British North America, the Society intended to assign Anglican ministers throughout the Crown’s colonies. This initiative conflicted with a tradition of local religious autonomy in many provinces. It also presaged a bold ecclesiastical strategy of establishing the Church of England in jurisdictions where an overwhelming majority of people, including Eastchester, preferred other Protestant denominations.

A conflict over religious autonomy seemed inevitable, and in the St. Paul’s parish the Church of England’s campaign created a struggle that resonated, in varying degrees, over the next several generations. It began when the Rev. John Bartow arrived at the new meetinghouse on November 19, 1702, and waited patiently for the Presbyterian minister Rev. Joseph Morgan to lead prayers in the morning. Following the conclusion of those observances, Rev. Bartow offered the first Anglican service in Eastchester, signaling the beginning of a new chapter in the town’s religious history.