Last updated: July 22, 2021

Article

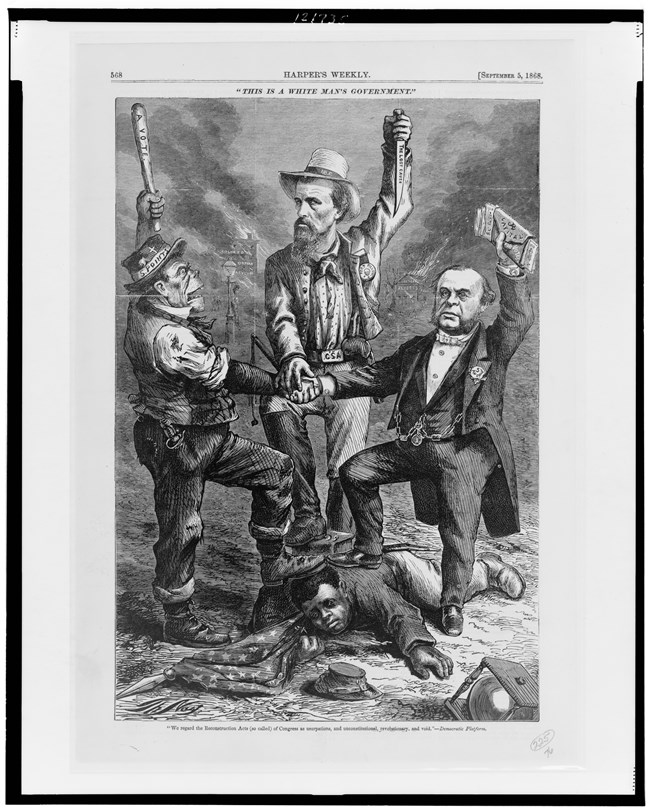

Reconstruction Era

Library of Congress

Difficulty in reconciling goals regarding reunion and emancipation appeared immediately upon Lincoln's death on April 14, 1865. President Andrew Johnson granted amnesty to all persons who had taken part in the rebellion, and restored all of their property. Johnson went on to appoint provisional governors for the former confederate states, but said nothing about accepting voting rights or protective civil rights for freed people.

Grant was uncomfortable with Johnson's Reconstruction policy, but loyally supported the President. Congressional elections in 1866 gave "radical republican" opponents a veto-proof majority and control of reconstruction, and the ten southern states were divided into five military districts. Their commanders, who were ordered to see that federal laws were enforced and the new civil administrations were established, reported directly to Grant. As Congress battled President Johnson through 1866 and 1867, leading to his impeachment, Grant was compared to George Washington as an "indispensable man" who led the nation to victory and could insure peace and stability.

Library of Congress

"I see in him the vigilant, firm, impartial, and wise protector of my race from all the malign, reactionary, social, and political elements that would whelm them in destruction. He is the rock-bound coast against the angry and gnawing waves of a storm-tossed ocean saying, thus far only shalt thou come.

Wherever else there may be room for doubt and uncertainty, there is nothing of the kind with Ulysses S. Grant as our candidate. In the midst of political changes he is now as ever—unswerving and inflexible. Nominated regularly by the time honored Republican party, he is clothed with all the sublime triumphs of humanity which make its record. That party stands to-day free from alloy, pure and simple. There is neither ambiguity in its platform nor incongruity in its candidates. U.S. Grant and Henry Wilson . . .—the soldier and the Senator—are men in whom we can confide. No two names can better embody the precious and priceless results of the suppression of rebellion and the abolition of slavery."

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

The 1868 Republican National Convention unanimously selected Ulysses S. Grant to run for president, and they adopted his quote "let us have peace," at the Republican Convention as their campaign slogan. The Democratic National Convention selected Horatio Seymour, former Governor of New York, as their candidate for president instead of former President Andrew Johnson. Ulysses S. Grant won the presidential election against Democrat Horatio Seymour, winning 52.7% of the popular vote and receiving 214 votes from the electoral college, while Seymour only received 80. At the age of 46 years old, Grant became the youngest President elected.

Library of Congress

Grant emphatically rejected this version of southern defeat, stating in 1878 that “we never overwhelmed the south…what we won from the south we won by hard fighting.”

Gradually, the meaning of “the lost cause” came to refer to a romantic vision of a vanished society based on honor, chivalry, and the pastoral life which was quickly disappearing in industrial America

In addition to lobbying for Veterans’ benefits, the Grand Army Republic kept the memory of the “union cause” alive by contesting the pro-confederate “lost cause” version of civil war history