Last updated: August 31, 2023

Article

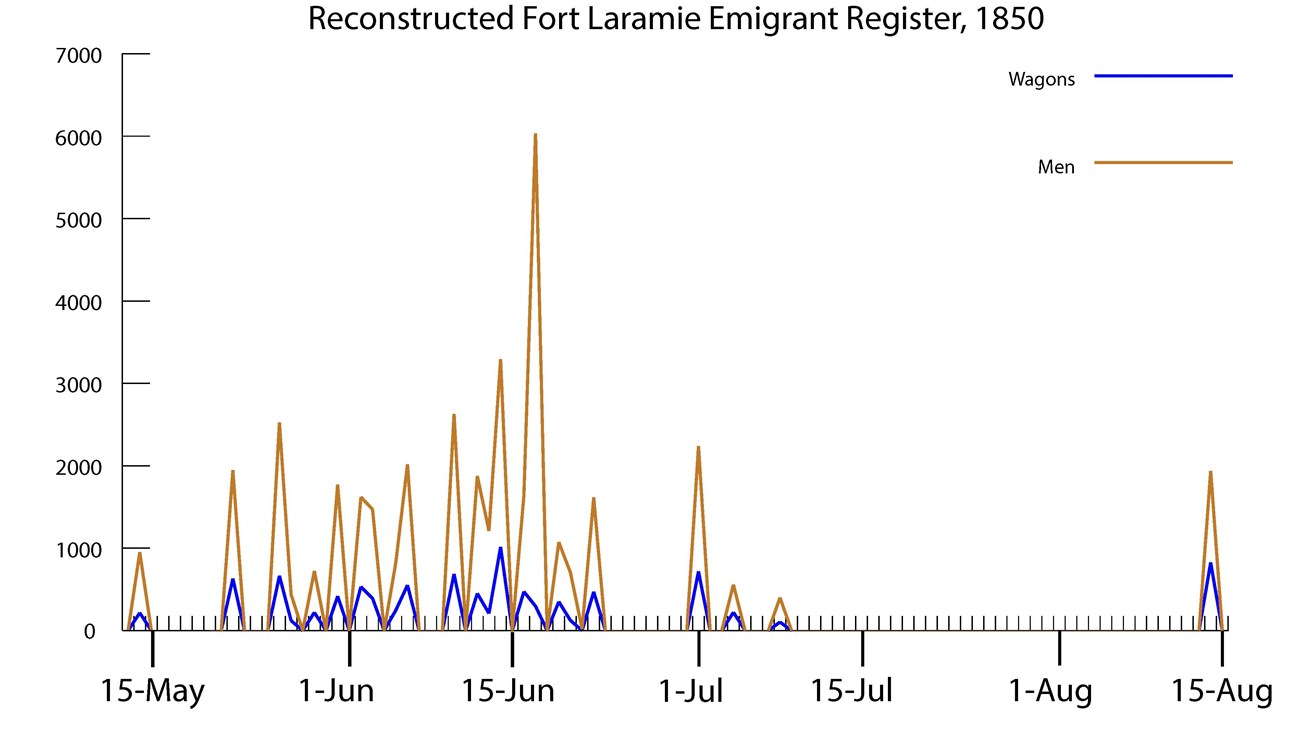

Reconstructed Fort Laramie Emigrant Register, 1850

NPS Image

(Overland travel was largely a matter of timing. As this graph shows, most westward-bound migrants passed Fort Laramie between mid-May and early July, allowing them to reach their destinations before winter weather set in. Although this graph only depicts the 1850 travel season, other years would have followed the same basic pattern. The data in this graph comes from John D. Unruh, The Plains Across: The Overland Emigrants and the Trans-Mississippi West, 1840-60 (University of Illinois Press, 1979), 122.)

Nineteenth-century overland migration is one of the best documented processes in American history. Journals, letters, sketches, and guidebooks paint vivid pictures of the varied landscapes and emotions that migrants experienced on their way west. Yet despite this rich body of evidence, there is no official count of how many people undertook the journey.

Some of the best data we have comes courtesy of officers at Fort Laramie, who counted passing travelers in the year of 1850. Despite the small sample size, the fort—a critical stop for travelers en route to places as far flung as Utah, Oregon, and California—was a good place to gauge the flow of westward migration.

The primary military outpost on the Northern Plains, Fort Laramie also offered supplies, services (like blacksmiths or doctors), and information about traveling conditions. Noticing the stream of migrants, Army officers at the fort tried to maintain an exact tally of westbound traffic; they counted only men and wagons, however, excluding women, children, and livestock from their calculations.

Although there are no known copies of the register itself, migrants cited its statistics in diaries and letters. Newspaper correspondents did the same thing in their articles. In his book The Plains Across, historian John D. Unruh (1937–1976) pieced these numbers together to offer a detailed look at the 1850 travel season.

What can these numbers tell us? For starters, they show that the trail could be crowded; 1850 was, after 1852, the second busiest year on the overland trails. One 1850 traveler reported passing 500 wagons—not people, wagons— in one day. Tempers flared, and incidents of “road rage” were not uncommon.

Migrants traveled in different ways. Take a look at June 17, which saw over 6,000 men pass Fort Laramie—but only about 300 wagons. July 1 saw less than half the men (roughly 2,300) but more than twice the wagons (over 700). What gives?

Unruh estimates that over 80 percent of 1850 migrants were headed to California. On days like June 17, with a roughly 20 to 1 ratio of men to wagons, most travelers were likely gold-seekers traveling light. Making the trip without their families, they opted for mules, wheelbarrows, or even just backpacks. Days like July 1, with an approximately 3 to 1 ratio of men to wagons, tell a different story. Remember, the Fort Laramie register didn’t count everyone. The low ratio of men to wagons suggests more families traveling by wagon, with a lot of women and children left uncounted. Migrants like these probably intended to settle in the rich agricultural valleys of Oregon or California.

Statistics also highlight the importance of timing for overland migration. The 1850 register shows most travelers passing through Fort Laramie between late May and late June, which would have put them on track to reach California or Oregon by early fall. If migrants left too early, the grasses along the trail might not be ready to feed their animals. If they departed too late, however, they might get caught in an early winter storm in California’s Sierra Nevada. Those passing through on August 14 may have suffered such a fate. There is a chance, though, that they intended to winter among the Latter-day Saints in the Salt Lake Valley—a choice made by the roughly 900 who stayed there through the winter of 1850–51.