Last updated: December 12, 2025

Article

Re-Growing Southeastern Grasslands

L to R: NPS, USGS/Diane Larson, and NPS/Calzarette

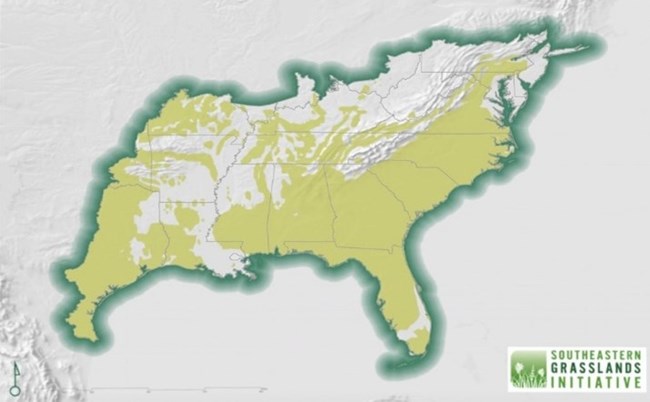

Southeastern Grasslands Initiative

Please DO Disturb

One thing all grasslands have in common is the need for disturbance. Without regular disturbance, grasslands slowly transition into forests through the natural process of succession. As the forest matures and the canopy closes, grassland plants, which require open sunny conditions, disappear. Historically, fires (caused by lightning strikes or Native Americans managing lands for crops and game), grazing by bison and other herbivores, and even flooding kept grasslands open. This allows sun-loving plants (known as heliophytes) to flourish. Within the last 100 years however, human-induced changes to disturbance regimes, including active fire suppression and the loss of large grazers, have resulted in the conversion of many historic grasslands into forests. Although forest ecosystems are invaluable, the replacement of grasslands by forests homogenizes the landscape and decreases biodiversity.

John Burwell

More Than a “Land of Grass”

Despite what the name suggests, grasslands are much more than just grasses. Native grasslands are composed of a rich diversity of non-woody plants, including flowering forbs, sedges, rushes, and grasses, with relatively few or no trees. These plant groups play different functional roles in the grassland ecosystem. Grasses and sedges provide cover for wildlife, forage for mammals, nesting habitat for birds, and overwintering habitat for insects. Flowering forbs also provide cover and forage, but their main role is supplying nectar for pollinators as well as seeds and berries for birds and wildlife. Grasslands with a high diversity of forb species, provide food resources throughout the growing season—from early spring when insects and other animals emerge from hibernation to late fall when many birds are preparing to migrate, and insects are beginning to settle in for the winter. In addition to supporting a wide range of species, grasslands also play a key role sequestering carbon, cycling nutrients, building soil, and contributing to overall soil health and water quality.Disappearing Biodiversity Hot Spots

Unfortunately, more than 90% of native grasslands have been developed or converted for agriculture, making them one of the most rapidly disappearing habitats in the world. This widespread loss of grassland habitats has pushed many grassland species to the brink of extinction. Grassland bird populations have dropped by 53% since 1970—more than any other bird group. In Maryland alone, 70% of the state's rare, threatened, and endangered plant species are associated with open, grassland habitats. The remnant grasslands that persist, however, are considered biodiversity hotspots because they support an inordinate number of species, more than any other ecosystem type in America! The eastern Coastal Plain, for example, contains approximately one-third of the plant species found in North America (Noss 2013).Grasslands in the National Capital Region

Luckily there’s a lot that can be done to protect and restore southeastern grasslands. Many national parks in the NCR are working on conserving, restoring, and connecting grassland habitats. This includes converting agricultural lands into native grasslands, reintroducing fire to the landscape, and studying the flora and fauna of existing open grasslands. Here are a few examples of grassland projects ongoing as of fall 2022.Manassas National Battlefield Park has converted more than 1,000 acres into native grasslands and meadows, including open land within a power line right-of-way. Since the work began in 1996, the park has seen grassland birds, pollinators, and other wildlife flourish.

The Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park, Antietam and Monocacy National Battlefields, and Manassas National Battlefield Park are working with researchers at the US Geological Survey (USGS) to assess the effects of different meadow management strategies on bee communities. As of 2021, more than 200 species of flowering plants and 45 species of bees have been documented!

Rock Creek Park has converted eleven small turf fields ranging from 0.1 to 4.5 acres into native meadows. These meadows support numerous plants and insects and are a highlight for many visitors to the park, showing that grassland conservation does not need to be large to be effective.

NPS

Harpers Ferry has also been working with University of Delaware ornithologists to survey grassland birds and raptors. In 2021 they documented 28 successful nests out of a total of 45 nests found. Breeding species included eastern meadowlark, grasshopper sparrow, red-winged blackbird, and bobolink.

Antietam National Battlefield is converting 43 acres of crop field into grassland in the park’s Otto Farm. This year, the park will plant a cover crop of winter wheat and barley along with native grasses like switchgrass and big bluestem, and then follow up by planting non-woody flowering plants (forbs). The goal is to expand the farm’s native grassland area to 113 acres and create a biodiverse open habitat similar to what was present in 1862 during the Battle of Antietam.

NPS/Strickler, Thiel

Several of these projects are facilitated by agreements through the Chesapeake Watershed Cooperative Ecosystems Studies Unit (CW CESU). To learn more, contact CW CESU Research Coordinator Danny Filer at 301-491-2465.

NPS/Thiel/Strickler

References

Noss, R. F. (2013). Forgotten grasslands of the South: natural history and conservation. Island Press.Rosenberg, K.V., Dokter, A.M., Blancher, P.J., Sauer, J.R., Smith, A.C., Smith, P.A., Stanton, J.C., Panjabi, A., Helft, L., Parr, M. and Marra, P.P. (2019). Decline of the North American Avifauna. Science, 366, pp.120-124.

Tags

- antietam national battlefield

- catoctin mountain park

- chesapeake & ohio canal national historical park

- george washington memorial parkway

- harpers ferry national historical park

- manassas national battlefield park

- monocacy national battlefield

- national capital parks-east

- prince william forest park

- rock creek park

- wolf trap national park for the performing arts

- grasslands

- southeastern grasslands

- meadows

- prairie

- pollinator

- grassland birds

- ncr

- restoration

- natural resource quarterly

- fall 2022

- science

- nature

- pollinators