Last updated: September 15, 2025

Article

Rapid Riparian Decline in Rocky Mountain National Park: Understanding the Loss—and Pathways for Restoration

E. W. Schweiger

Background

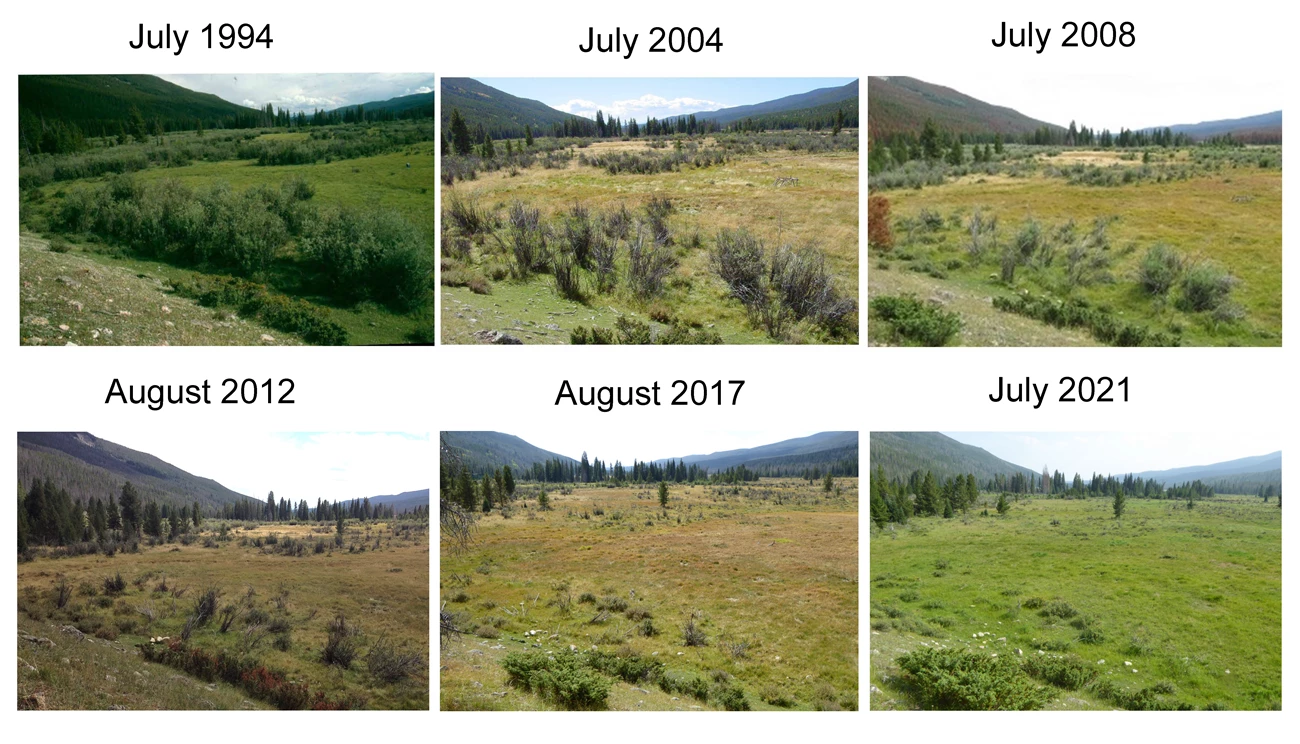

Rocky Mountain National Park (RMNP), one of America's most iconic natural areas, has undergone a dramatic collapse in the biologically rich, riparian, willow-dominated wetlands of the Kawuneeche Valley since the mid-20th century (Figure 1). For centuries, this area was shaped by the close relationship between tall willows and beavers, creating lush ecosystems that supported wildlife and helped buffer the land from extreme climate. But today, the valley tells a different story.

David Cooper

Data collected since the 1950s have revealed a rapid ecological collapse, with a 94% loss of beaver ponds since 1953 and a 98% loss of tall willows since 1999. The likely culprits? A combination of excessive browsing by elk populations and an expanding moose population, compounded by a drying climate and the loss of beavers. Without intervention, this iconic ecosystem may never return.

What Does It Mean for an Ecosystem to Collapse?

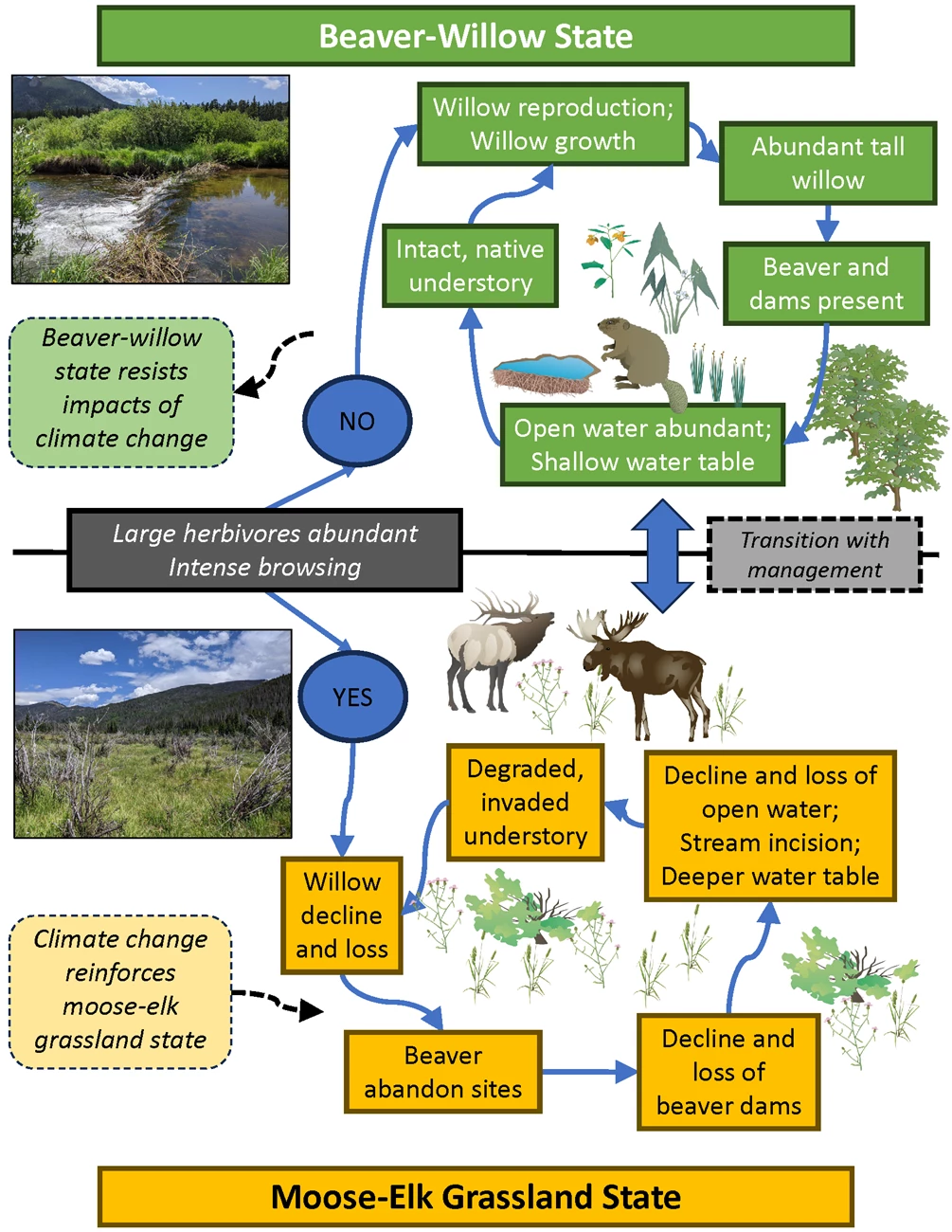

Ecological collapse is the rapid, and sometimes abrupt, loss of ecosystem biodiversity, function, and services. A collapse is a tipping point when ecosystems transition into fundamentally altered states, often characterized by increasingly degraded conditions. In the Kawuneeche Valley, the once-prevalent beaver–willow wetland state collapsed into a moose–elk–grassland state. Dense thickets of willows that once shaded cool beaver ponds are now open grasslands with short, overbrowsed shrubs and non-native, invasive plants. These aren’t just cosmetic changes; they affect how water moves through the landscape, the quality of wildlife habitat, and the ability of the ecosystem to bounce back from drought and wildfire.

Why It Matters

Riparian wetlands cover only a small portion of the park but play an outsized role in supporting more biodiversity than their area would suggest. The shift from willow dominated wetlands shaped by beaver activity to grasslands shaped by large herbivore use isn’t just a local issue, it reflects broader challenges facing protected areas worldwide in a warming, human-influenced world.

This new grassland state is largely stable, meaning natural processes alone are unlikely to restore historical wetlands. Returning to a beaver-willow state will require extra effort, such as active restoration of ground water, supporting the return of beaver, and controlling invasive plants (Figure 2).

David J. Cooper, E. William Schweiger, Jeremy R. Shaw, Cherie J. Westbrook, Kristen Kaczynski, Hanem Abouelezz, Scott M. Esser, Koren Nydick, Isabel de Silva, Rodney A. Chimner

- The Beaver-willow state starts with no large herbivores abundant, intense browsing. It then flows into a circular path that flows as follows:

- Willow reproduction; willow growth

- Abundant tall willow

- Beaver and dams present

- Open water abundant; shallow water table

- Intact, native understory

- And back to willow reproduction; willow growth

- The Moose-Elk Grassland state starts with yes, large herbivores abundant, intense browsing. It then flows into a circular path as follows:

- Willow decline and loss

- Beaver abandon sites

- Decline and loss of beaver dams

- Decline and loss of open water; stream incision; deeper water table

- Degraded, invaded understory

- And back to willow decline and loss

- Between the two states, there is a double-sided arrow indicating that the states can transition with management

- The diagram also shows that climate change reinforces the moose-elk stage, whereas the beaver-willow state resists the impact of climate change.

What Caused the Collapse?

While climate change played a role and may increasingly do so in the future, the evidence points squarely at overgrazing by large herbivores:

-

Elk populations are not regulated by predators. In summer, they occupy the Kawuneeche Valley, where they feed on grasses and willows.

-

Moose feed almost exclusively on willows in summer in RMNP. Their population has grown beyond what the Kawuneeche Valley’s riparian wetlands can support.

-

Together, elk and moose browsing pressure severely reduced the height and extent of tall willows, eliminating the food and building material that beavers require.

- Once beavers disappeared, water tables dropped, ponds dried out, and the entire system shifted.

Can the Ecosystem Recover?

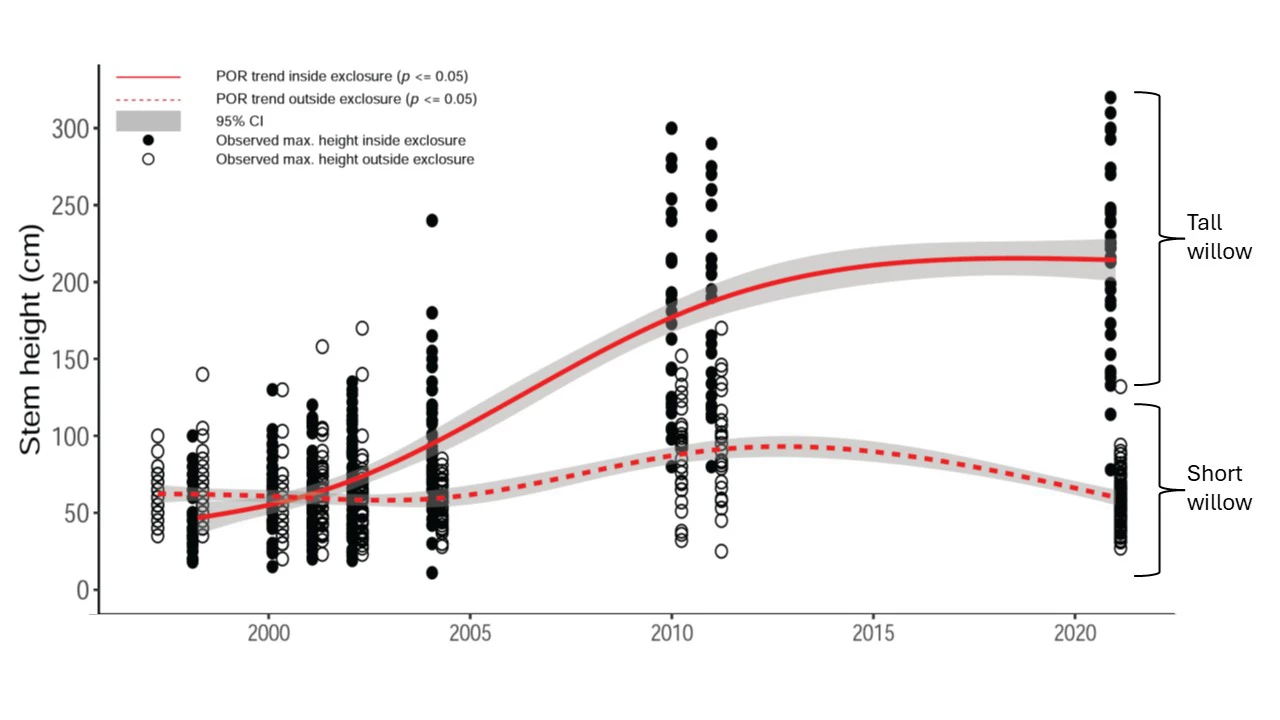

Yes—but not without help from park managers. The good news: where elk and moose browse have been dramatically reduced, willows can grow back. Starting in 2008, the park constructed twelve fences, or exclosures, encompassing a total of 183 acres of willow as part of the Elk and Vegetation Management Plan. After 15 years, willows inside the fences grew 0.91 meters while outside the fences, willows only grew 0.04 meters (Figure 3). One of these exclosures is in the Kawuneeche Valley. Before and after photos show the return of tall willows (Figure 4). With tall willows in place, beavers have returned to this exclosure.

David J. Cooper, E. William Schweiger, Jeremy R. Shaw, Cherie J. Westbrook, Kristen Kaczynski, Hanem Abouelezz, Scott M. Esser, Koren Nydick, Isabel de Silva, Rodney A. Chimner

The graph shows tall willow stems increasing in height inside exclosures, while willow stems outside exclosures remained short or declined.The vertical axis shows willow stem height in centimeters from 0 to 350.

- The horizontal axis shows years from 1998 through 2022.

- The solid red line represents the trend in maximum willow stem height inside exclosures. It begins below 100 cm in the late 1990s, rises steeply after 2005, and levels near 250–300 cm by 2020.

- The dashed red line represents the trend in maximum willow stem height outside exclosures. It begins near 70 cm in the late 1990s, fluctuates around that level through 2010, and then declines gradually to below 50 cm by 2020.

- The shaded gray area shows the 95% confidence interval for the trends.

- Individual data points are shown as black filled circles for observed maximum stem height inside exclosures and open circles for observed maximum stem height outside exclosures.

- Brackets at the right margin mark the separation of tall willow inside exclosures and short willow outside exclosures.

NPS

Recovery takes:

- 2–5 years to see noticeable willow growth.

- 10–20 years for willows to grow tall enough to support the food and dam building needs of beavers.

Restoration will require invasive plant control, less elk and moose browse, better connections between streams and floodplains, planting willows where erosion has occurred, and installing structures that act like beaver dams. These actions could contribute to beavers returning to the landscape, as has occurred in other exclosures in the park.

What is the Park Doing?

The park is at a crossroads due to the urgency required to address ecosystem degradation that has occurred before remnants from the willow state, including old living willows that could produce seed if not heavily browsed, disappear. With the data from this paper, Rocky Mountain National Park has chosen to resist the ecosystem change that has occurred by restoring the beaver–willow ecosystem, where possible, and its associated benefits: biodiversity, water storage, fire resistance, and scenic value. This approach contrasts other potential management actions such as directing change by managing for a more native grassland (even if beavers and willows cannot return widely) or accepting change and allowing the current moose–elk–grassland state to persist.

This study underscores an important truth: even protected areas are not immune to collapse. Factors such as regional wildlife dynamics, changing water balance, and missing predators can unintentionally contribute to ecological imbalances. That’s why active stewardship is essential.

To meet the challenge, RMNP is partnering with several organizations, including Northern Water, Rocky Mountain Conservancy, The Nature Conservancy, Grand County, the Town of Grand Lake, the US Forest Service, and faculty at Colorado State University, who serve as science advisors, to restore ecological function of riparian wetlands in the Kawuneeche Valley.

Restoration is still possible, but the opportunity to act is narrowing.

Information in this article was summarized from Rapid riparian ecosystem decline in Rocky Mountain National Park by D. J. Cooper, E. W. Schweiger, J. R. Shaw, C. J. Westbrook, K. Kaczynski, H. Abouelezz, S. M. Esser, K. Nydick, I. de Silva, R. A. Chimner. Content was edited and formatted for the web by E. Rendleman.