Last updated: September 22, 2022

Article

"Raids Have A Wonderful Effect..." - Raids and Panic of the Gettysburg Campaign

Library of Congress

The American Civil War touched the lives of almost every American. Women watched their husbands and brothers march off to war, and fathers and sons fought together on fields of battle, sometimes side by side and occasionally under the enemy’s flag. Factories were built and burned to the ground and millions of enslaved people wondered what this fighting would mean for their futures.

On more than a few occasions, farmers would watch their fields of corn turn to fields of the fallen, and when newspapers reported the movements of either army, the citizens and communities that lived and worked in their path may have let out a collective shudder. Both the Union and Confederate armies brought with them much more than death and destruction. They brought their horses and mules, their wounded and diseased, and their undying hunger. They needed food, water, clothing, medicine, shoes and anything else that was available for the capturing. To meet the ever-growing needs of an army, soldiers, usually cavalrymen, would scout out the surrounding areas for provisions.

Often, local markets, businesses, and farms were thoroughly searched for any useful or necessary goods. Wagon trains and railroad cars were captured, raided, and destroyed when appropriate.

Not only were these raids helpful in replenishing rations and supplies, but they were often also successful in causing panic and chaos among communities. In some cases, raiders would also destroy railroads, bridges, and communication lines to undermine the enemy and weaken support systems. Newspapers often reported on these events and began fostering more fear among communities. The Camden Confederate, a Southern newspaper out of Camden, South Carolina, often updated its readers on the war and the raids that had been happening nearby. In summer of 1863, the paper reported, The Mississippian says no less truthfully than encouragingly:

We believe that one hundred men, with double barrel shot guns, can always out fight five hundred raiders, by ambushing them properly, and evincing the coolness and courage of determination. With the advantages of ambuscades and our knowledge of the country, and facilities for taking the enemy by surprise, one man ought to be equal to five. There is no doubt of the fact that we can prevent these raids, and let every man solemnly resolve to do it.[1]

Since the majority of the war had been fought south of the Mason-Dixon line prior to 1863, Southern cities and towns had most harshly felt the realities of war. As rumors of a new Confederate campaign targeting northern soil began to circulate, panic and fear began to ignite in parts of southern Pennsylvania. Where were the rebels headed? Harrisburg? Washington? What did they want? Is any of this true?

Though General Robert E. Lee began his Gettysburg Campaign on June 3 1863, it’s not until June 12 that Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin addressed the concerns of his citizens. He confirmed rumors that a “large rebel force” was endangering the state and called upon Pennsylvanian men to enlist for the defense of their “own homes, firesides and property.'[2] Governor Curtin immediately began calling for more troops and preparing the state for impending invasion.

As both state and local governments attempted to rally troops and fill new enlistment quotas from President Lincoln in Washington, business owners and citizens began to fear for the safety of their property. The Pennsylvania Central railroad suspended regular work to instead build blockhouses that could be used to defend bridges that would be too difficult and expensive to replace.[3] Businesses packaged and shipped off some of their most valuable merchandise to cities further east. Rural Pennsylvanians also began preparing for the arrival of Confederate forces after General Darius Couch, commander of the Department of the Susquehanna during the Gettysburg Campaign, warned communities of the Cumberland Valley that they may be in harm's way. Reportedly, citizens ran off their horses and cattle and buried tack and tools in haystacks. One man supposedly even hid his work horse in the basement of his home to avoid seizure by the Confederates.[4]

Library of Congress

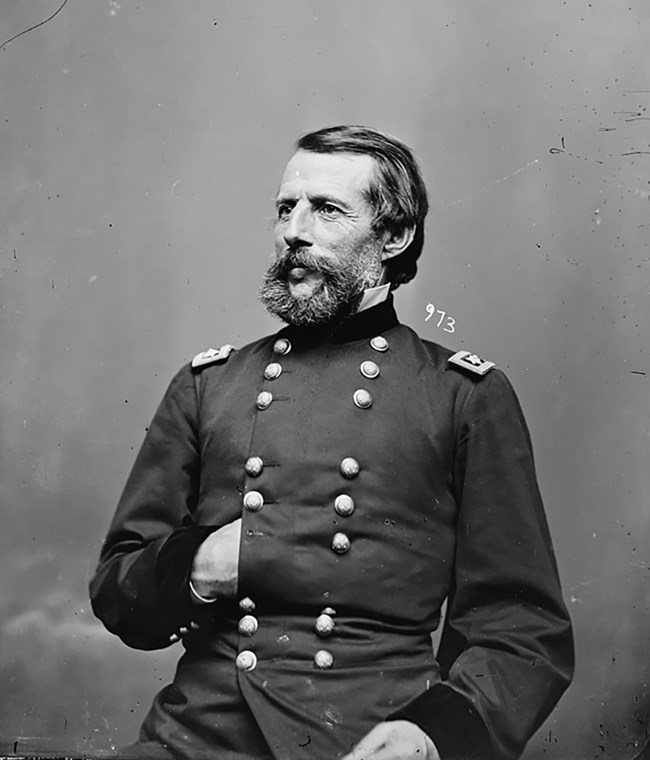

On June 14 1863, reports reached Gettysburg from Chambersburg that growing fears over a potential Confederate invasion were rising, as were rumors that Union General Robert Milroy had been attacked in Winchester, Virginia.[5] The reports were true and rebel troopers recalled being overwhelmed by the supplies found in Milroy’s wagons, including “clothing, corn, flour, bacon, shoes, boots, hats, sugar, tea, coffee, raisins, almonds, Malaga grapes, maple sugar,” and more.[6] Their capture was successful in more ways than one. Not only were they able to replenish their supplies, but they ignited fear in the north.

Just a few days after the capture of General Milroy’s supplies and troops in Winchester, panic in Harrisburg began to spike. Reports capture the chaos, recalling:

At the bridge and across the river the scene was equally excited. All through the day a steady stream of people, on foot and in wagons, young and old, black and white, was pouring across it from the Cumberland valley, bearing with them their household goods and all manner of goods and stock. Endless trains, laden with flour, grain, and merchandise hourly emerged from the valley and thundered across the bridge and through the city. Miles of retreating baggage wagons, wagons filled with calves and sheep tied together, and great old-fashioned furnace wagons loaded with tons trunks and boxes, defiled in continuous procession down the pike and across the river, raising dust that marked the outline of the road as far as the eye could see.[7]

As this panic and fleeing continued in southern Pennsylvania, Union General Erasmus Keys asked for permission to continue raiding the countryside of Virginia stating, “raids have a wonderful effect by producing discontent among the people against the Confederate government. They demand protection, and, if the raids are repeated, the old and sick will call home their sons and brothers to protect their homesteads, and in that way the rebel army will be melted away.[8]

Virginia, which had been devastated until this point in the war, was looking forward to some much-needed relief. Confederate soldiers noticed the difference in Pennsylvania’s fruitful land not long after crossing the Mason-Dixon line. They were said to have an abundance of fresh produce, bacon, eggs, butter and syrup from the countryside and indulge in such a way that Confederate General Richard Ewell voiced his concern that if the men were to carry on in such a manner, they may become fat.[9]

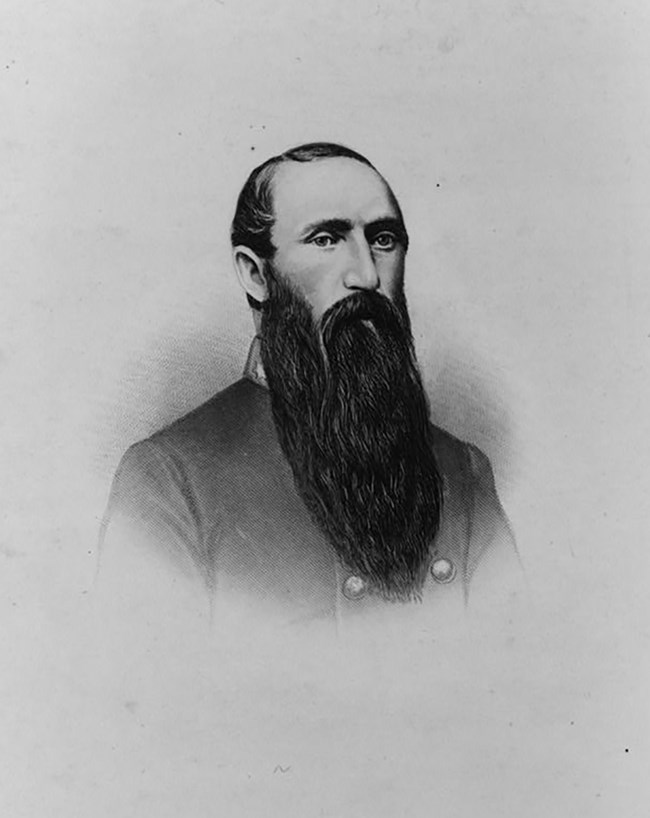

Out of all the southern Pennsylvania communities that saw waves of rebel forces passing through, the city of Chambersburg was hit the hardest by the invasion. Their stores and streets were overrun by rebel soldiers on multiple passes through the area. Most notably, on June 16, 1863, Confederate cavalry commander Albert Jenkins and his two thousand horsemen rode into town with a list of demands. Local merchants were forced to accept Confederate money, all public and private weapons were seized and burned, and a railroad bridge was destroyed. Freed and fugitive African Americans were wrangled up, considered “captured contraband” by the southern army, and sent south. Some were fortunately able to escape, and a few were released, but reports estimate that over fifty people captured during raiding of the area were sent back to slavery.[10]

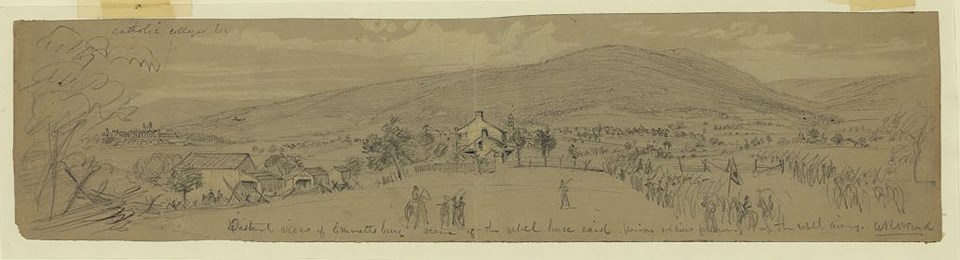

rebel army.” -sketch by Alfred Waud

Library of Congress

In the days leading up to the Battle of Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, Confederate cavalry trampled through the towns and cities of Franklin and Adams county. By the end of June, they would finally arrive in Gettysburg for the first time. On June 26th, local professor and resident of Gettysburg, Michael Jacobs, remembered the arrival of rebels in Gettysburg, recalling, “shouting and yelling like so many savages from the wilds of the Rocky Mountains; firing their pistols, not caring whether they killed or maimed man, woman or child.'[11]

Neither the citizens of Gettysburg, or soldiers in blue and grey could imagine the carnage that would result here just four short days later.