Last updated: February 14, 2025

Article

The Racial Integrity Act, 1924: An Attack on Indigenous Identity

Document Bank of Virginia, Library of Virginia

At the beginning of the 20th century, the eugenics movement was gaining momentum. Eugenics is the practice of controlling reproduction to alter the genetic characteristics of a population. Some advocates of eugenics believe that methods like selective “breeding” and sterilization would benefit human society by promoting beneficial traits. But who decides which traits are desirable and which are undesirable? Historically, eugenics has been used to justify white supremacy, resulting in discriminatory policies and heinous practices like forced sterilization.

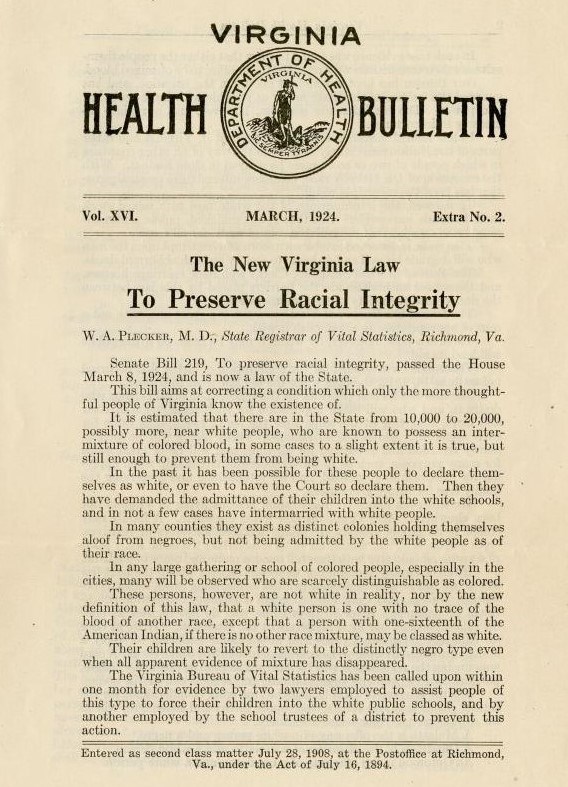

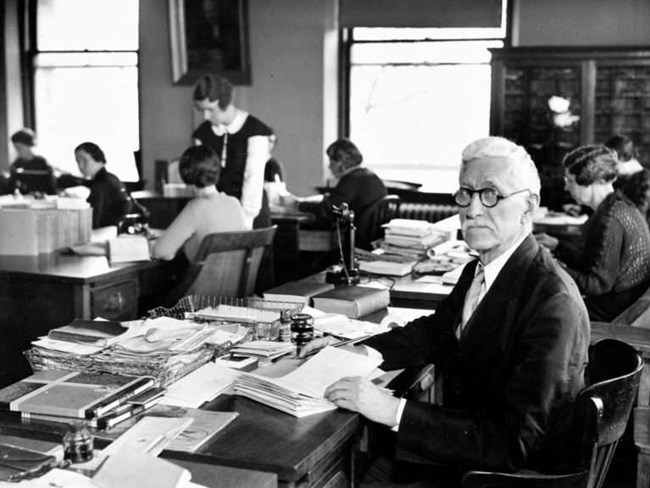

One such policy was the Racial Integrity Act, which was passed in Virginia in 1924. The new law prohibited interracial marriage and ushered in a long period of discriminatory racial designation administered by the government. One of the Act’s main proponents was a physician named Walter Ashby Plecker. As the head of Virginia’s Bureau of Vital Statistics from 1912-1946, Plecker was responsible for ensuring that all infants born in Virginia received birth certificates that included their racial designation. An active eugenicist, Plecker used bureaucracy as a weapon against Black and Indigenous people across the state of Virginia.

It wasn’t until 1967 that the Racial Integrity Act was overturned by the United States Supreme Court in the Loving vs. Virginia case. Nevertheless, Plecker’s legacy of racial discrimination still impacts communities today, in particular Tribal communities. Many find it difficult to document their ancestral lineage due to the “paper genocide” that identified all non-white individuals as “colored” regardless of their identity. Despite this challenge, seven Tribes have gained federal recognition in Virginia.

Eugenic Origins of the Racial Integrity Act

Eugenics argued that “genetic purity” could lead to a more utopian society. The idea was to select and support the proliferation of “desired” heritable characteristics through control over the parental rights of specific communities.

Sterilization had become one of the many tools employed by eugenicists across the world, including Nazi Germany. On July 14, 1933, the Nazi government passed the Law for the Prevention of Genetically Defective Progeny, allowing the mass sterilization of the “hereditarily weak,” such as the deaf and blind, those with physical deformities or mental illnesses, and various groups under persecution such as the gay and lesbian community and Jews.

The United States was no stranger to these cruel “treatments” and likely informed the rest of the world on eugenicist practices. In 1907, the state of Indiana had passed the world’s first sterilization law. And, in 1924, the “The Virginia Sterilization Act” was enacted, initially targeting the intellectually disabled.

Walter Scott Copeland Papers, 1880–1954. Accession #5497. Special Collections, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Va.

Walter Plecker Champions the Act

Walter Ashby Plecker was born in Augusta County, Virginia in the spring of 1861. After securing a medical degree from the University of Maryland in 1885, he relocated to Hampton, Virginia and began working as the public health officer for Elizabeth City County. He took a strong interest in obstetrics and helped reduce birth-mortality rates by 50%. However, he was also a staunch advocate of eugenics and white supremacy.

In 1912, Plecker was selected to serve at the head of the newly created Bureau of Vital Statistics in Virginia. The responsibility of the office was primarily to ensure that all infants born in Virginia received birth certificates, including racial designation. In the following years, Plecker pushed for the creation of Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act.

Passed in 1924, the act outlawed interracial marriage and added strict definitions to racial classifications. It also criminalized the falsification of racial identity on legal documents, stating that, “the term ‘white person’ shall apply only to such person as has no trace whatever of any blood other than Caucasian.” Any who fell outside of this definition were to be identified as “colored.” While registration of racial identity was technically voluntary, it was required for things such as registering for the draft, enrolling in school, marrying, or issuance of a birth certificate. Racial identification was not limited solely to “blood traces.” The law allowed racial identity to be determined by things such as physical features and even family names.

The Pocahontas Exception

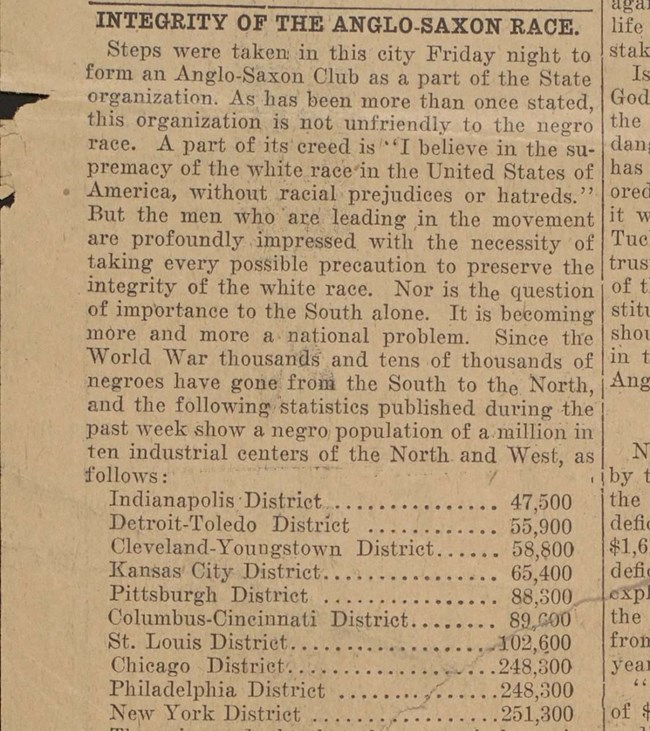

Existing laws had allowed any person with one sixteenth or less of American Indian blood and no other non-caucasian blood to identify as white. This was because many prominent white Virginian families had long espoused themselves to be descendants of Pocahontas and John Rolfe. This became known as the “Pocahontas Exception,” and allowed many white families to maintain their ancestral connection to Pocahontas without nullifying their white racial identity.

Richmond Times-Dispatch, January 8, 1935

However, Plecker feared that this would lead many mixed-race Virginians to pass themselves off as having Native American ancestry instead of black ancestry in order to afford themselves the privileges associated with being identified as white. He writes that “some of these mongrels, finding that they have been able to sneak in their birth certificates unchallenged as Indians are now making a rush to register as white” and that “one hundred and fifty thousand other mulattoes in Virginia are watching eagerly the attempt of their pseudo-Indian brethren, ready to follow in a rush when the first have made a break in the dike.” As a consequence, he decided that “there are no native born Virginia Indians free from negro intermixture.”

In 1930, the General Assembly officially updated the Racial Integrity Act to define a “colored” person as anyone who holds even “one drop” of “negro blood.” As far as Plecker was concerned, this meant that all Native Americans in Virginia would now be identified as “colored.” Any birth certificates predating 1924 that identified a person as “Indian” were overwritten as “colored,” as assigned by the state. His racist investigations and practices were comprehensive, issuing lists of surnames descendant from “free negroes” to be used in the racial identification of “colored” persons.

Impact on Indigenous Identity and Tribal Recognition

“We were the third ranks in what was predominantly a two-race society.”

-Chief Stephen Adkins, Chickahominy Tribe

Plecker’s strict definitions of whiteness and blackness led to a mass erasure of Virginia Indian identity. As a result of his efforts, Virginia Indians often have difficulty in proving an unbroken lineage, one of the many requirements to becoming a federally recognized Tribe. Federal recognition represents a government-to-government relationship between the United States and Tribes. It acknowledges Tribal sovereignty and their ability to self-govern within their community.

In reflecting upon federal recognition, members of many different Tribes discuss the unique requirement of “proof.” Sally Latimer of the Monocan Nation stated in a PBS interview that, “we’re one of the only groups of people, race, that has to prove who we are.” Chief Adams of the Upper Mattaponi echoes this idea, saying that recognition, “is sort of a silly thing if you think about it, being recognized by the state for who you are, because no other culture in this land has to do that to get this recognition that they should have. That should come with just being here.” For some, such as Chief Adkins of the Chickahominy Tribe, federal recognition serves as the Commonwealth’s “day of reckoning” for having allowed Plecker’s “paper genocide” to occur. Chief Branham of the Monacan Nation says that “I didn’t need federal recognition for me, but I wanted it so my grandmother and my mom and dad could be proud of who they were.” As Chief Adams puts it, “it is a pride issue.”

Duane Berger / Chesapeake Conservancy

Furthermore, Indigenous knowledge is being sought out by the federal government to help assess and solve issues like climate change and the pandemic. While celebrating this relationship and recognition, many Tribal members and leaders remember the long path that it took to achieve them. Federal recognition is just one way that a few Tribes have sought to formally reclaim their identity despite the heinous attacks of Plecker and beyond in twentieth-century Virginia.

Today, there are seven federally recognized Tribes in Virginia: the Chickahominy Tribe, the Eastern Chickahominy, the Monacan Nation, the Nansemond Nation, the Pamunkey Tribe, the Rappahannock Tribe, and the Upper Mattaponi Tribe.

Plecker’s Death and Loving vs. Virginia

On August 2, 1947, Walter Plecker was killed by a vehicle strike in Richmond, Virginia. His policies and actions continued to impact communities for decades after his tenure and death. It wasn’t until twenty years later that the prohibition on interracial marriage was overturned in the 1967 Loving vs. Virginia case.

Richard Loving, a white male, and Mildred Jeter, a woman with both African American and Native American ancestry, had left Virginia to get married in Washington, DC. A short time after their return to Virginia, they were arrested for their violation of Virginia’s ban on interracial marriage. After pleading guilty, the Lovings were sentenced to either a year in jail or a conditional ban from returning to Virginia as a couple for the next 25 years. The Lovings established themselves in D.C. and decided to file a suit against the Virginia court that had sentenced them. They sued on the grounds that the condemning sections of the Virginia state code were unconstitutional in their inconsistency with the Fourteenth Amendment, which provided equal protection under the law regardless of race.

The suit was rejected by the state court but was picked up for review by the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals. The appeals court upheld the constitutionality of Sections 20-58 and 20-59. Though sections 20-58 and 20-59 utilized racial classifications in their definition of criminal offense, the appeals court upheld the idea that neither statute violated the guarantee of equal protection, since the sentences were equally imposed upon both Loving (white) and Jeter (Native American and African American). After this ruling, the Lovings decided to take their case to the United States Supreme Court.

The supreme court presented a unanimous ruling that reversed the Lovings’ convictions. Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote that the justices “reject the notion that the mere ‘equal application’ of a statute containing racial classifications is enough to remove the classifications from the Fourteenth Amendment’s proscription of all invidious racial discriminations.” They did not agree that the statutes racial classifications served any “legitimate overriding purpose independent of invidious racial discrimination.” In other words, the racial classification used in statutes 20-58 and 20-59 had no other purpose than racial discrimination, voiding their equal protection under the law.

The Supreme Court’s ruling meant the Lovings had won. They overturned the couple’s conviction and consequently invalidated laws against interracial marriage in 15 other states across the country.

Walter Plecker Asserted that Virginia Indians No Longer Exist, December 1943 (Library of Virginia)

A Conversation with Two Chiefs (Virginia Indian Archive)

Letter from Walter Plecker (1943) (Virginia Indian Archive)

Trump signs bill federally recognizing 6 Virginia tribes (NBC 12)

Tribal nations in Virginia mark five years since federal recognition (Indian Country Today)

A Smithsonian Scholar Revisits the Neglected History of the Chesapeake Bay’s Native Tribes (Smithsonian Magazine)

Walter Ashby Plecker (1861–1947) (Encyclopedia Virginia)

Loving v. Virginia (Britannica)

Forced sterilization policies in the US targeted minorities and those with disabilities – and lasted into the 21st century (The Conversation)

Popular support for eugenics (Britannica)

Tags

- captain john smith chesapeake national historic trail

- george washington memorial parkway

- manassas national battlefield park

- prince william forest park

- star-spangled banner national historic trail

- wolf trap national park for the performing arts

- indigenous history

- captain john smith chesapeake national historic trail

- native american history

- racial prejudices

- eugenics

- discrimination

- african american history

- indigenous chesapeake post 1600

- virginia

- native american

- tribal

- race

- african american

- paper genocide

- ncr

- star-spangled banner national historic trail