Part of a series of articles titled Women's History in the Pacific West - Pacific Islands Collection.

Previous: Olivia Robello Breitha

Article

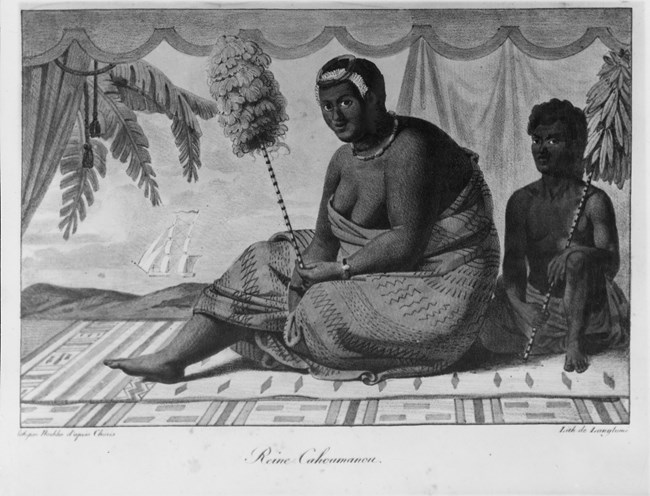

Original drawing by Louis Choris. Hawai'i State Archives (PP-96-6-003).

Queen Ka‘ahumanu was one of the most powerful women in Hawaiian history, whose decisions would affect her people for centuries. As the favored wife of the powerful King Kamehameha I and the kuhina nui (regent or co-regent) of her stepsons Kings Kamehameha II and III, Ka‘ahumanu demonstrated a keen political sense and a strong understanding of power. She also likely spent some time in the area that is now encompassed by Pu‘uhonua O Hōnaunau; the Ka‘ahumanu Stone in the park is named after her.

Ka‘ahumanu’s political experience began during childhood and continued into her young adulthood. She was born in Maui sometime between 1768 and 1777 to noble parents. Her mother, Namahana, was related to the king of Maui and her father, Keeaumoku, was a high chief from Kona and advisor to King Kamehameha I.1 As a child, she was sent to live in the household of the powerful thirty-year-old King Kamehameha I (who was from Hawai‘i Island but was consolidating power over other islands as well) in preparation to become one of his wives. Although he married approximately twenty other women, Ka‘ahumanu was reportedly his favorite. He honored her by designating her as pu‘uhonua, meaning that like the physical place of Pu‘uhonua O Hōnaunau, she could offer sanctuary and absolution with her presence or authorization.2 Kamehameha I also appointed Ka‘ahumanu the guardian of his son and successor, and he allowed Ka‘ahumanu to attend meetings of his high council. When her father died, she took his place on the high council, becoming the only woman at the time to do so.3

According to oral history and European observers, Ka‘ahumanu’s relationship with Kamehameha could be tempestuous.4 The stone that bears her name in Pu‘uhonua O Hōnaunau National Park appears in one of these traditional tales of conflict. According to the story, Ka‘ahumanu fled after a quarrel and swam with her dog to Inanui. Her husband’s agents pursued her and set fire to the village he thought was harboring her. She hid under a large stone—now the Ka‘ahumanu Stone—until the king’s agents saw her dog, found her, and delivered her to the king.5

After King Kamehameha I died in 1819, Ka‘ahumanu consolidated her power and enacted multiple reforms. She asserted that the deceased King Kamehameha I had favored her as regent for his son Liholiho. When Liholiho became King Kamehameha II, he appointed her to be the first kuhina nui of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i.6 Although Kamehameha II was the king, in practice Ka‘ahumanu had as much authority and power governing the islands as her stepson. She played a major role in abolishing the ancient religious ‘ai kapu laws that prohibited men and women from eating together and barred women from eating certain foods.7 She also placed restrictions on chiefs who demanded large amounts of fish from poor subjects as taxation. In 1821 she married the king of Kaua‘i, Kaumuali‘i, to cement her family’s control over that island as well as Hawai‘i and Maui.8

After Kamehameha II died and was succeeded by his brother Kamehameha III, Ka‘ahumanu continued to exercise power. When Christian missionaries arrived in the mid-1820s, Ka‘ahumanu embraced them and their faith, possibly looking to replace the religious laws she and Kamehameha II had abolished. When she adopted Christianity, she ordered that older religious buildings and artifacts, including some at Pu‘uhonua O Hōnaunau, be abandoned and destroyed; it was only through the actions of another Christian chiefess, Kapi‘olani, that the sacred bones of royal ancestors at Pu‘uhonua O Hōnaunau were saved from destruction.9 Ka‘ahumanu also created a new legal system based on the Christian Ten Commandments, encouraged literacy in the Hawaiian language so that people could read the Bible, and supported the creation of schools to teach it. Because she accepted Christianity, more white Protestant missionaries were permitted in the islands, which would have far-reaching and sometimes devastating effects on her people for centuries.10

Queen Ka‘ahumanu was an astute politician and one of the most powerful rulers in early nineteenth-century Hawai‘i. She navigated the reigns of multiple kings and the arrival of Christian missionaries in a period that saw Hawai‘i grow into a larger and more united kingdom. She died on June 5, 1832, leaving behind a society forever changed by her leadership.

Part of a series of articles titled Women's History in the Pacific West - Pacific Islands Collection.

Previous: Olivia Robello Breitha

Last updated: March 29, 2022