Last updated: September 6, 2021

Article

Protecting Life and Property: Passing the Ku Klux Klan Act

Library of Congress

Finding Justice During the Reconstruction Era

What is the meaning of justice? Who gets to define the term? During the Reconstruction era (1863-1877), Congress passed constitutional amendments and legislation to abolish slavery, promote equal protection of the laws, establish birthright citizenship, and guarantee fair elections. Not everyone agreed with this vision of justice, however.

Frank Bellew/Library of Congress

A Deplorable State of Affairs

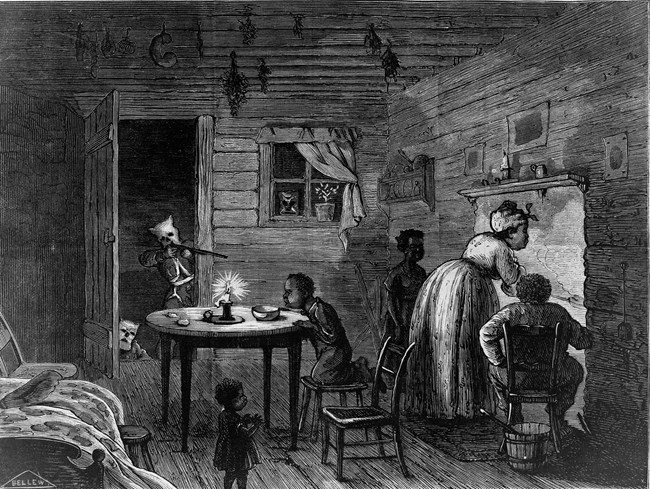

On October 29, 1870, Louis Foy wrote to President Ulysses S. Grant. Foy was a formerly enslaved African American who now owned a twenty-acre farm in Terrell County, Georgia. Facing terroristic threats from the Ku Klux Klan, Foy described his terrifying ordeal. “I was badly beaten and shot in my own house by some white rebels.” Unable to get protection from the local Justice of the Peace, “I [now] wish to appeal to you as my President,” said Foy. During Reconstruction, countless African Americans living in the South sought the help of new federal laws protecting citizenship and voting rights.

Library of Congress

The Power of the Pen

The wounds of the American Civil War were still fresh when Ulysses S. Grant became the nation’s 18th President on March 4, 1869. Addressing the nation during his First Inaugural Address, President Grant acknowledged this pain but asked all citizens to approach the future “calmly, without prejudice, hate, or sectional pride.” He also understood that peace could not be achieved without the enforcement of laws protecting all rights. For the President, “security of person, property, and free religious and political opinion in every part of our common country, without regard to local prejudice” was essential to peace.

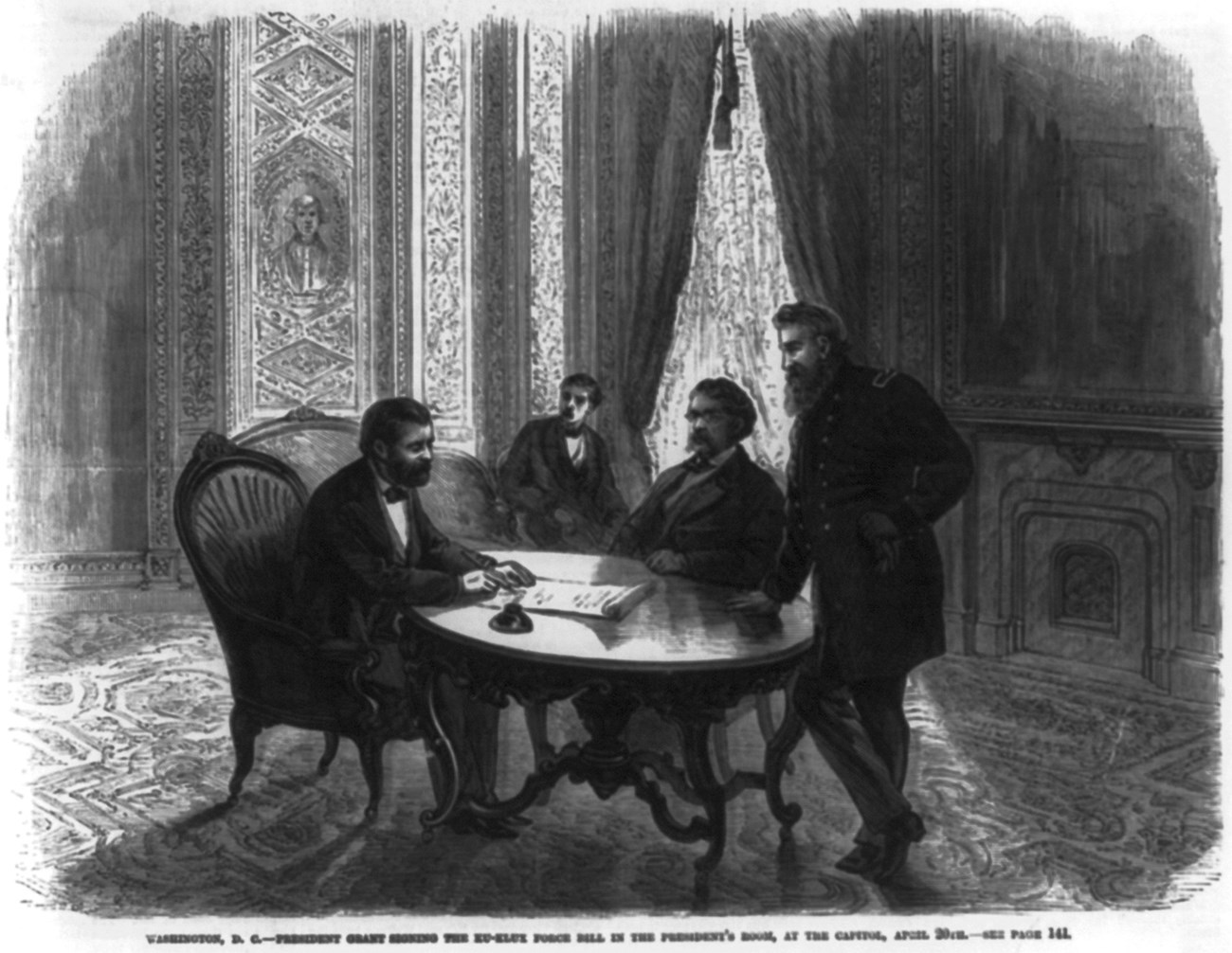

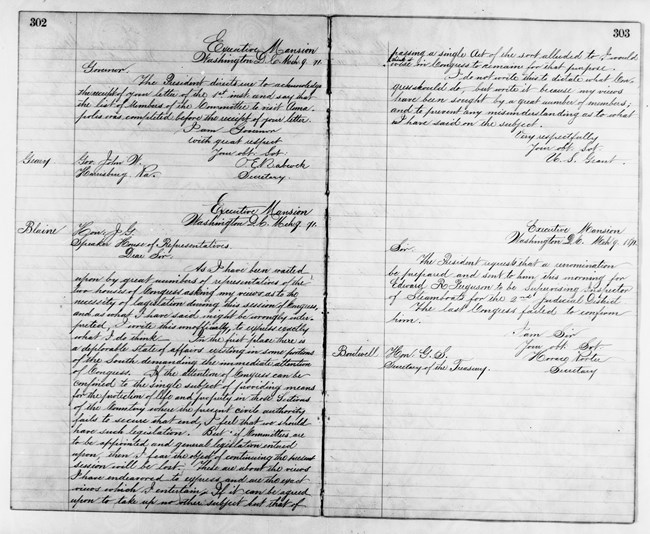

The 15th Amendment was ratified and the Department of Justice established in 1870. Collectively these acts aimed to end racial discrimination at the polls and better enforce civil rights laws at the federal level. But the violence continued. Writing to Speaker of the House James G. Blaine on March 9, 1871, the President suggested that more legislation was necessary. If Congress passed a bill authorizing the use of the military to stop racial terrorism by groups like the Ku Klux Klan, Grant would eagerly sign the bill to ensure “the protection of life and property” for all citizens, regardless of background.

Library of Congress

Enforcing Justice

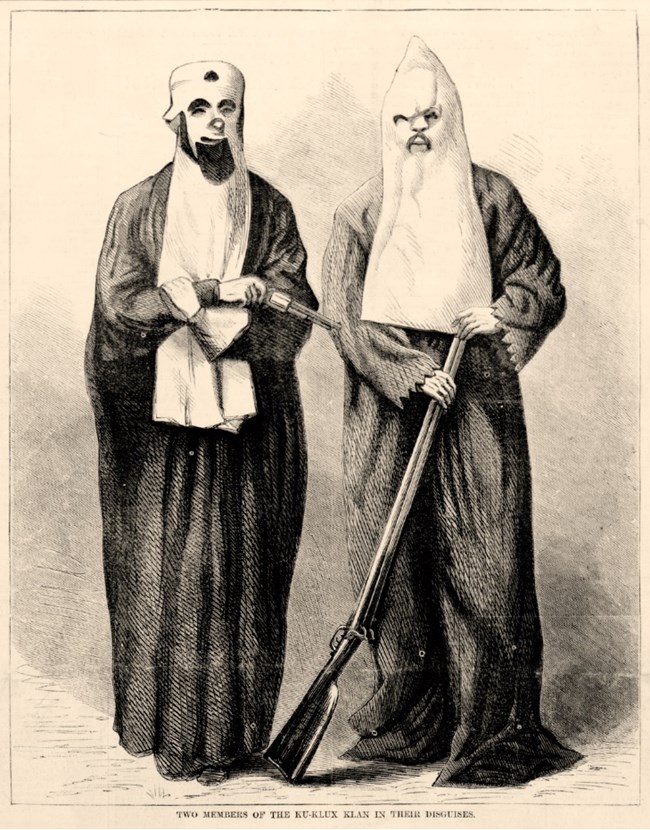

Between May 1870 and April 1871, Congress passed three “Enforcement Acts” targeting white supremacist violence. The first law prohibited voter discrimination and banned the use of terror to prevent people from voting on account of their race. The second law put federal elections under federal supervision in Southern states under military rule. The third law broadened President Grant’s powers to enforce these laws. Six months after the Third Enforcement Act was passed, President Grant mobilized the military in nine South Carolina counties where Ku Klux Klan activity was rampant.

Library of Congress

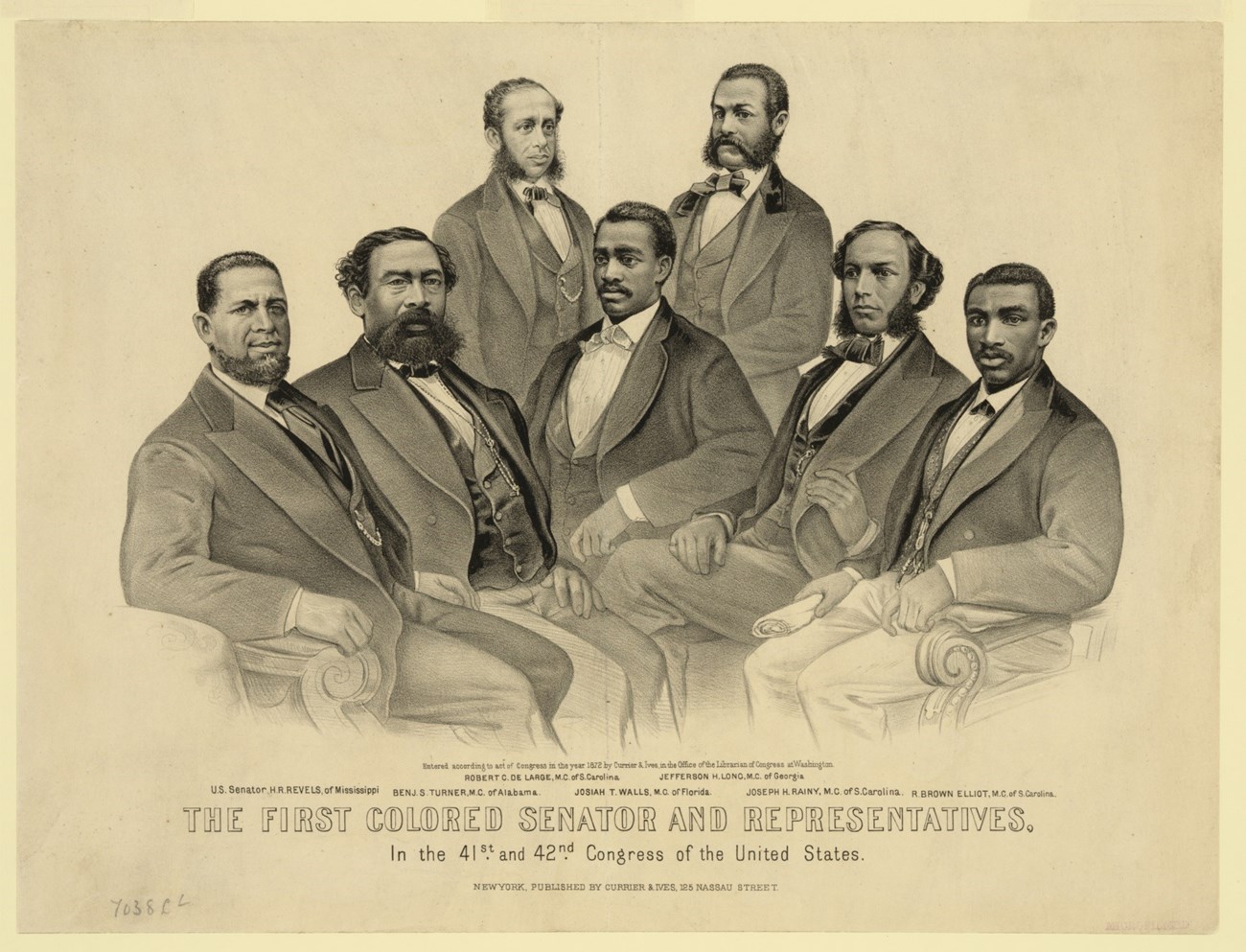

Voting on the Ku Klux Klan Act

Congress voted to approve the Third Enforcement Act, sometimes referred to as the “Ku Klux Klan Act,” on April 20, 1871. This law empowered the President to suspend habeas corpus (the right to challenge an unlawful imprisonment in court) and mobilize the U.S. military wherever vigilante groups committed violence against African Americans. Among those who voted in support of the law were African American Congressmen Robert De Large, Robert B. Elliot, Joseph Rainey, Benjamin S. Turner, and Josiah T. Walls. In the above image from left to right, De Large stands in back left, Turner is seated second from left, Walls is seated in center, Rainey is seated second from right, and Elliot is seated far right.

Library of Congress

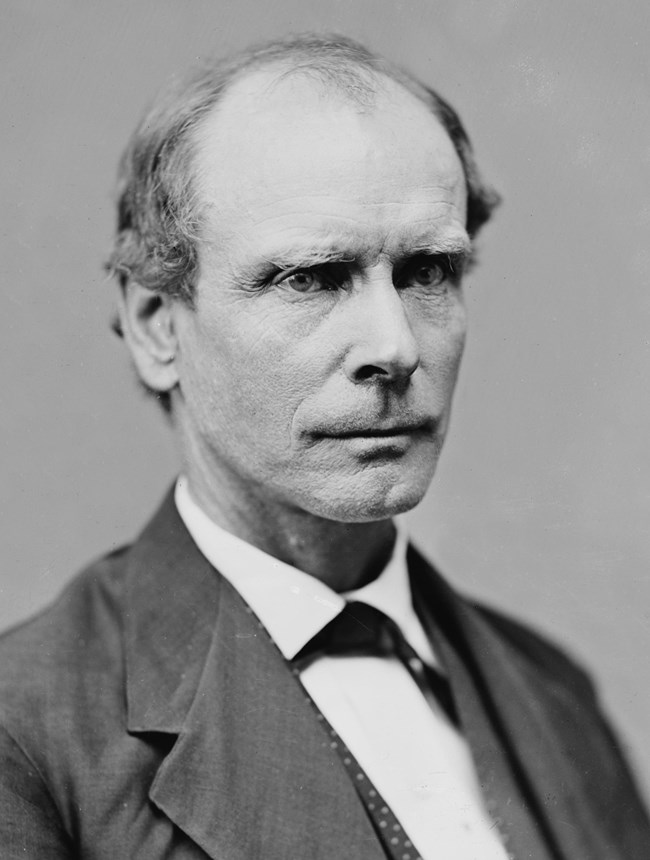

President Grant's Right Hand Man

Amos Akerman was President Ulysses S. Grant’s Attorney General from June 1870 through December 1871. Although born in New Hampshire, Akerman lived most of his adult life in Georgia as a lawyer and farmer. He owned eleven enslaved African Americans and served in the Confederate Army at the rank of Colonel during the Civil War. After the war, however, Akerman joined the Republican Party and supported Ulysses S. Grant for the presidency in 1868. As Attorney General, Akerman oversaw a federal investigation of the KKK. He personally led U.S. Marshals and the U.S. Army against the KKK after President Grant suspended habeas corpus in nine South Carolina counties in October 1871. Over the next few months, Akerman successfully indicted 3,000 KKK members throughout the South, 600 of whom were later convicted of crimes. Akerman’s actions helped destroy the KKK and ensured that local, state, and federal elections in 1872 were free and fair.

Smithsonian National Museum of American History

Was it Effective?

In the short-term, President Grant’s use of the Enforcement Acts effectively destroyed the KKK, partially fulfilling his goal of “securing to all citizens . . . the peaceful enjoyment of the rights guaranteed to them by the Constitution and laws.” However, acts of violence against African Americans continued during Reconstruction and beyond. The Jim Crow Era (1880s-1960s) led to mass voter disenfranchisement, racial segregation, and lynchings against African Americans. Civil Rights legislation in the 1960s created a “Second Reconstruction” for equality and freedom, but debates about justice continue today.

Timeline of Events

-

March 4, 1869: Ulysses S. Grant is inaugurated as the nation’s 18th president and gives his First Inaugural Address, supporting ratification of the 15th Amendment.

-

February 3, 1870: 15th Amendment ratified.

-

May 31, 1870: The First Enforcement Act is passed by Congress and signed into law by President Grant.

-

June 17, 1870: President Grant selects Amos Akerman as U.S. Attorney General.

-

June 22, 1870: Congress establishes the Department of Justice.

-

July 22, 1870: President Grant sends troops to stop KKK activities in North Carolina upon request of Governor William W. Holden.

-

February 28, 1871: The Second Enforcement Act is passed and signed into law by President Grant.

-

March 9, 1871: President Grant writes to Speaker of the House James G. Blaine and suggests that Congress pass another law for “providing means for the protection of life and property” where civil unrest continued.

-

April 20, 1871: The Third Enforcement Act is passed and signed into law by President Grant.

-

October 12, 1871: President Grant suspends habeas corpus in nine South Carolina counties and sends troops to suppress the KKK.