Last updated: June 18, 2023

Article

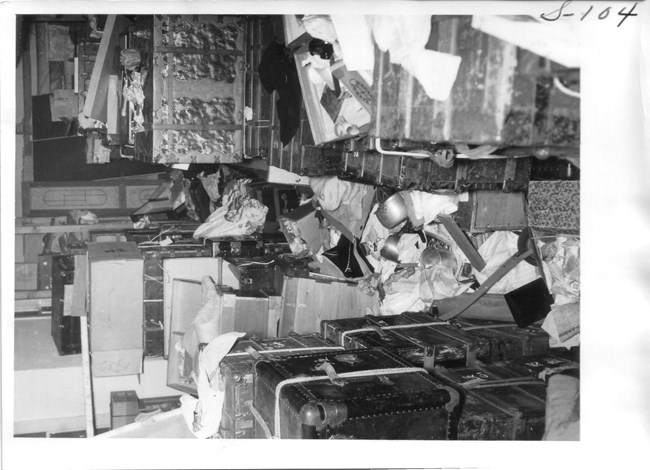

Property Claim of Yasuhei Nagashima

Dorthea Lange, National Archives and Records Administration

CLAIM OF YASUHEI NAGASHIMA

[No. 146-35-8. Decided December 29, 1950]FINDINGS OF FACT

This claim, in the amount of $807.75, is for loss resulting from WRA's erroneous sale at public auction of property stored by claimant in the WRA warehouse at Tule Lake Segregation Center. Claimant originally made claim for his loss with the Department of the Interior under the Act of December 28, 1922 ( 42 Stat. 1066, 31 U. S. C. § 215). The claim, timely filed, had notbeen disposed of at the time of enactment of the Act of July 2, 1948, and it was therefore transmitted to the Attorney General for consideration under the latter Statute by letter from the Solicitor for the Department of the Interior dated August 6, 1948. Claimant was informed of this fact shortly after receipt of the letter and advised to submit a new claim, the necessary claim form being furnished him for the purpose. The form, duly executed by claimant, was received by the Attorney General on December 16, 1949. The statement of claim contained therein was identical with that originally presented to the Department of the Interior, the sole "cause of action" alleged being loss from WRA's erroneous sale of claimant's stored property. Claimant was born in Japan of Japanese parents and has at no time since December 7, 1941, gone to Japan.

On December 7, 1941, and for some time prior thereto, claimant actually resided at 236 East Second Street, Los Angeles, California, and was living at that address when evacuated on May 9, 1942, under military orders pursuant to Executive Order No. 9066, to the Santa Anita Assembly Center. At the time of his evacuation, claimant owned a 1936 Chevrolet 1½-ton truck, together with certain household furniture and effects and a considerable amount of personal clothing. Claimant transported his furniture and clothing to the assembly center on his truck and on arrival at the center retained control over the former but turned the truck over to representatives of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco who sold it to the Army.

Claimant was transferred from the Santa Anita Assembly Center to the Heart Mountain Relocation Center, and from there, later, to the Tule Lake Segregation Center. WRA shipped claimant's furniture and clothing to his new locus on the occasion of each transfer. In November 1944, claimant was permitted to transfer from Tule Lake to the Crystal City Internment Camp, Crystal City, Texas, whither he chose to go as a voluntary internee in order to be with his brother who had been involuntarily interned at this camp and was awaiting deportation to Japan.

At the time of his departure from Tole Lake, claimant desired to take his furniture and clothing with him but was informed that the Crystal City camp had no facilities for their storage. In consequence of this fact, claimant proceeded to store his furniture and clothing in the WRA warehouse at TuleLake. Claimant remained at Crystal City until November 13, 1945, when he was released because of his status of voluntary internee and permitted to return to Los Angeles.

Shortly after his resettlement in the latter city, claimant requested the Los Angeles District Office of WRA to have his furniture and clothing forwarded to him from Tule Lake. Accordingly, on December 4, 1945, the Los Angeles WRA District Office wrote the Tule Lake authorities of claimant's request, informing them of claimant's Los Angeles address. On December 19, 1945, the Tule Lake Evacuee Property Officer replied to this communication by letter stating that claimant "has goods stored in our project warehouse" but that execution by him of the special WRA forms for requesting transportation of property would be necessary before shipment of claimant's goods could be effected. Apprized of this requirement, claimant immediately executed the required forms and on January 8, 1946, they were mailed to Tule Lake by the WRA District Office. Although the forms,properly executed, were duly received by the Tule Lake officials, no action was taken thereon and the matter was permitted to continue dormant through no fault of claimant, and despite the latter's continued appeals to the Los Angeles WRA District Office.

Finally, on April 1, 1946, the officials at Tule Lake, through error in no way imputable to claimant, sent claimant's property to the WRA warehouse at San Francisco where it was thereafter sold at public auction. Claimant had no notice or knowledge of the sale and received no part of the proceeds derived there from. The reasonable and fair value of claimant's property at the time of its loss was $308.75. Claimant was unmarried and sole owner of the property involved at the time of loss, and the loss has not been compensated for by insurance or otherwise.

National Archives and Records Administration

REASONS FOR DECISION

That claimant's $308.75 loss from WRA's erroneous sale of his property is compensable under the Act on the facts found admits of no dispute. As appears from the express terms of the Statute, the parenthesized clause of Section one specifically provides for recovery for "damage to or loss of personal property bailed to or in the custody of the Government or any agent thereof." In view of this fact and since claimant exercised due diligence and in no way contributed to causing the loss, it is clear that reimbursement necessarily must lie.

It should be noted in passing that the hearing in the instant case took place on April 14, 1950, and at that time claimant, in particularizing the property involved in the WRA sale, included certain items which were not listed in his claim form. Since the items all relate to the transaction originally alleged so that the variance is merely one of particularity, it is clear that these items are properly compensable. Kiyoji Murai, ante, p. 45; cf. Shigemi Orimoto, ante, p. 103. In addition to this material, claimant also introduced evidence at the hearing indicating the possibility of loss from the sale of his truck. Thus, claimant testified:

I should like to state here that when I made my original claim, I didn't claim anything for the truck because at that time I didn't know you could claim for anything after you sold it, no matter how little you got. I sold the truck at Santa Anita to the Army [and] I consider that I had a loss. I suppose it is too late now to claim for that loss.

From the foregoing, it would appear that claimant did not intend to present any claim for loss from the sale of the truck. If it be assumed, however, that claimant did intend to present a claim for such loss, there emerges the question of the effect thereon of the provision in Section 2 (a) of the Statute that all claims not presented within eighteen months from the date of statutory enactment shall be forever barred.

As appears from the authorities cited in Shigemi Orimoto, supra, it is elementary in law that an amendment to a pleading which merely amplifies or corrects the original statement of a "cause of action" or claim is not affected by a provision relating to limitation under the doctrine of "relation back." Where, however, such an amendment introduces new subject matter and an entirely new claim for relief limitation does not apply and constitutes an insurmountable bar. Applying these principles to the situation here presented, it is clear that if claimant's testimony at the hearing on April 14, 1950, be construed as an attempt to amend his claim so as to include loss from the sale of his truck, the amendment is barred by the provicisions of Section 2 (a) of the Statute. This is obviously true since the sale of the truck bears no relation whatsoever to the matters originally alleged in the claim, namely, the erroneous conduct of WRA, but represents the introduction of unrelated and entirely new subject matter and, therefore, of an entirely new claim or "cause of action." Cf. United States v. Andrews, 302 U. S. 517.

Despite the patent clarity of the foregoing, in a brief submitted by the Japanese-American Citizens League as amicus curiae, it is nevertheless contended that limitations is not here applicable. The basis of the contention is twofold: first, that the "cause of action" involved is not the conduct, transaction, or occurrence specifically set forth in the claim form but rather the general fact of claimant's evacuation and exclusion, and, secondly, that claimant should in any event be entitled to amend by application of Rule 15 (a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, 28 U. S. C. following § 723 (c).

The contentions require little discussion. The fallacy of the view that a claimant's "cause of action" is the general fact of his evacuation or exclusion was fully exposed in Mary Sogawa, ante, p. 126. As there pointed out, recovery under the Act is not predicated on any theory of recognition of the evacuation as constituting an actionable or tortious wrong in and of itself. To the contrary, the Statute represents an act of grace and recovery there under is restricted to specific items of property that may have been damaged or lost. Necessarily, therefore, the "cause of action" or basis of claim cannot be evacuation per se, but must be specific conduct and specific transactions and occurrences involving such property damage or loss. As for the applicability of the principles of free amendment contained in Rule 15 (a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, it is agreed that liberality in the allowance of amendments to claims should be applied under the instant Statute. The fact remains, however, that this principle is no wise affects the issue here involved, for "it is still the rule" in the Federal courts, as elsewhere, "that an amendment which states an entirely new claim for relief will not relate back" and is barred by limitation. See Moore's Federal Practice (2d ed.), p. 852, together with cases cited in footnote.

In light of the above, it is clear and we accordingly hold that if claimant did intend to amend his claim at the hearing so as to include an allegation of loss from the sale of his truck, the amendment is barred by the provisions of Section 2 (a) of the Statute.

301156-56---11