Last updated: September 29, 2022

Article

President Grant's St. Louis Horse Farm

NPS/ULSG Collections

Long before there was a “Grant’s Farm” animal park managed by Anheuser-Busch in South St. Louis County, there was an actual “Grant’s Farm” along both sides of Gravois Creek. The White Haven farm Ulysses S. Grant owned after the Civil War was supposed to be mainly a horse farm, but there was much more to the place than just horses. Grant wanted to grow grasses and hay for the horses, but he also grew other crops to help support the costs of running a horse farm. Orchards produced a range of fruits, particularly strawberries. Grant also had numerous cows that were raised on his farm. Horses, however, were Grant’s primary focus. Trotters, Thoroughbreds, and Morgan horses grazed the meadows of Grant’s land in the 1860s and 1870s.

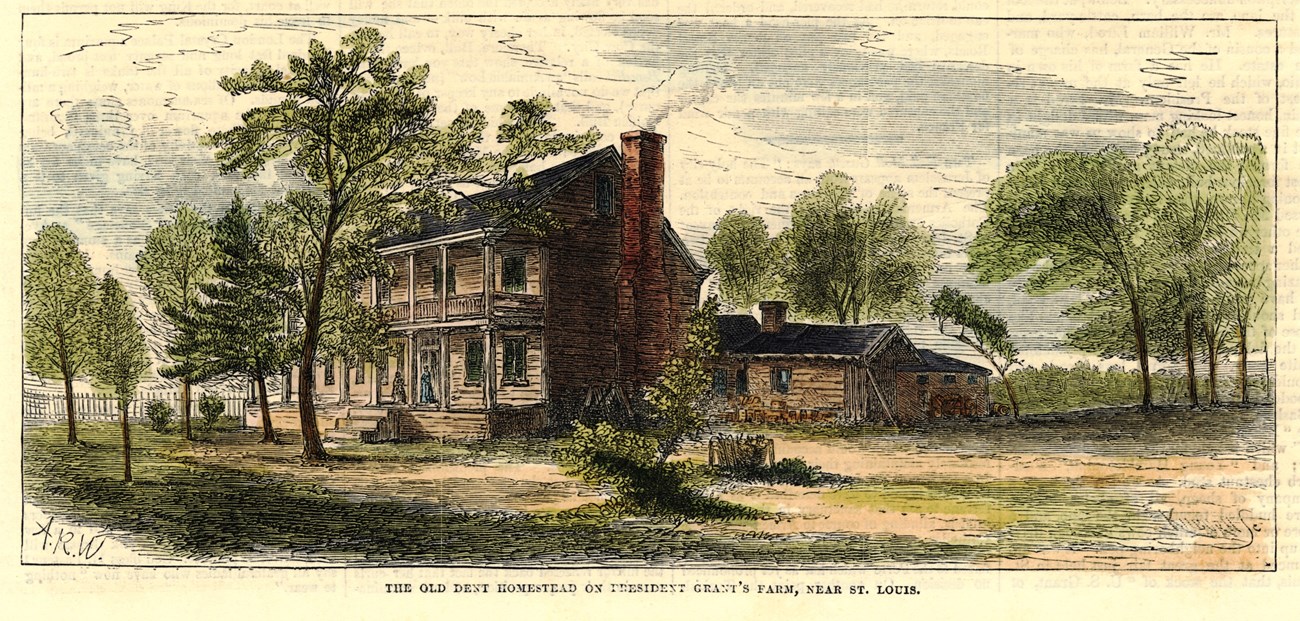

Grant had farmed White Haven prior to the Civil War from 1854 to 1859, when his father-in-law “Colonel” Frederick F. Dent owned the property. Although he struggled to support his family during these years, Grant still had an interest in managing the property. General Grant purchased his in-law’s property in 1866, roughly one year after the end of the American Civil War. In November 1866, Grant wrote to his father Jesse, “I now have some six or seven hundred acres of the Dent farm. It is my intention to stock it in a small way and keep about three men on it to put the place in meadow and to cultivate but very little beyond the orchards. There is now about twenty acres or more young orchard and with a few acres more set out in strawberries and other small fruit the principle work will be marketing hay and fruit and hawling [sic] manure to replace what is taken off the ground.” Before becoming president, Grant intended to visit the farm on a regular basis to provide direction in how he wanted the farm to be run. Being elected to the presidency complicated Grant’s vision of regularly visiting White Haven, but he decided to hire a caretaker to run the property in his absence. President Grant hired William Elrod, an Ohio farmer, to operate the White Haven estate. Elrod’s wife, Sarah Simpson Elrod, was a cousin of Grant’s. The Elrods moved to the main house and followed Grant’s instructions on caring for the property.

One of the first things Grant had carried out was tearing down numerous log cabins behind the White Haven estate. These cabins were the former homes of Colonel Dent’s enslaved farm hands. Grant wrote to Elrod in early 1867 noting that “besides a number of cabins on my place, which by the way I have directed shall all be pulled down, there are three good houses.” Grant had hoped to make the place self-sustaining as soon as possible. “I want to get all the ground in grass as soon as it can be got rich enough, except what will be in fruit. I will put from 25 to 40 acres in fruit as soon as we get possession of the whole place. I also want to get, as soon as I can, all the land fenced, the outside fence with board,” Grant told Elrod. Continuing he remarked, “there is now, or ought to be, a pile of cedar logs about the house which I intend to occupy when there. You might take them, at your convenience, to a saw mill and have them sawed into posts. You can then make plank fence, as far as they will go on the outer line of the farm….” Once the fencing was in place, Grant’s main hope was to have animals on the farm. Grant wrote to Elrod saying, “In the course of the next year I hope to be able to put up good stabling on the place you will occupy and to commence the raising of good stock.”

To raise horses on the farm, Grant needed to convert the bulk of Colonel Dent’s land from fruits and vegetables to grass and hay so they could be fed. He also needed to build a stable for the horses and a lime kiln to make lime for use in the fields. Grant instructed Elrod, “In using lime on the farm I would only put it on the clover fields. At all events try the clover first.” Grant, however, worried about the clover being bad for the horses’ digestive systems. He had Elrod let the horses graze fields of timothy instead. To Grant’s frustration, Elrod did not use the lime correctly. “You spoke of mixing lime with manure before putting it upon the ground! That will not do. Lime and manure should not be used at the same time. The lime would releace [sic] the Amonia, [sic] the most valuable ingredient, from the manure. If you get the lime kiln put about 80 bushels to the acre on all the cleared land as fast as you can and put no manure where you put lime until the latter is all taken up by the soil,” Grant instructed Elrod. Grant was still trying to get the land planted in grasses the horses could eat several years later. “Would it not be well to put in this fall as much wheat and timothy as you can find ground suitable to grow timothy upon? There is no use to attempt to raise grass on poor soil. Has the lime been tried on any of the fields? If so with what success?”

State Historical Society of Missouri

For Grant’s land on Gravois Creek to become a horse farm, a horse stable needed to be built. In 1871, Grant wrote to Elrod, “The stable is really very much wanted. I want it built if I am not to furnish too much money to build it with. I would change the plan however in one small particular. I would make at least eight box stalls, taking the place of sixteen or eighteen of the stalls, thus reducing the capacity of the stable from forty to thirty-two or thirty horses. More stables will have to be built afterwards, and I hope much better ones as the place pays the expense of them.” The stable, once built, would hold many of Grant’s beloved horses, especially the Trotters that he cared for so much. Today, this stable remains standing and serves as the museum at Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site. Even though the farm was intended to be primarily a horse farm, Grant wanted Elrod to raise cattle as well. The cattle would help bring income to the farm to make the place self-sustaining by producing milk and butter for profit. Grant wanted to have the best cattle he could get for the farm. In 1869, Grant let Elrod know he was sending some cattle from his vacation home in Long Branch, New Jersey to the farm. “Whilst at Long Branch I got an Alderny bull and two heifers to send to the farm. They are of the very purest blood. I expect before going back to Washington to stay to buy some four or six more heifers.” Despite these efforts, Grant left the cattle business when the farm began struggling. When William Elrod was replaced by Nathaniel Carlin in 1873, Grant had him sell off the calves and focus on bringing more horses to the farm.

Grant continued growing crops to raise money for the farm. To Elrod he noted that “if your crop of potatoes turn out well it will bring you in considerable money. Potatoes must be high this year for there will be none in this section to send to market-In setting out grapes next year I think I would try about one acre of the [Catawba] . . . Buy enough in the Spring to complete the lot you have commenced planting on, and then from your own cuttings extend as far as looks profitable [sic]”. Grant sought grapes that might be good for making wine. “I find that the Concord grape has no market now, as a wine grape, and to raise more than you have now set out will probably prove a loss. At your convenience some time find out just what grape will find a ready market and plant none other.” Grant also instructed Elrod to grow corn.

A new road and fence were built through the property during this time. Grant wrote Elrod, “I was aware that a new road had been made up Gravois Creek, but supposed it to be far enough from the bank to admit of a fence between the road and the creek. If this is not the case, and you propose to build the fence I spoke of, I would put the plank fence North of the road and take the rails from there to the South side of the creek. I will not have a barn built until I go out and locate it and give the plans.” In 1872, The Missouri Pacific Railroad installed a line through the farm near this fence. In return for the use of Grant’s land, a train station was installed at White Haven. The Kirkwood and Carondelet railroad line offered a direct pathway for President Grant to send animals, supplies, and other shipments from the White House to White Haven.

Grant often asked how his horses were doing. In 1870, Grant asked Elrod, “How is the colt doing? He should be handled enough to keep him gintle [sic]. He is finely disposed and if there is any thing in pedigree or form he should be very fast. I do not want him tried however in the least until I have him put in the hands of a regular trainer.” The farm was still producing horses in 1873, and Grant desired to have them trained properly. “…I want my stallions driven, he told his friend Charles Ford, “and also the colts as they become old enough. I would like also to have the stallions prepared for the fair, together with a suckling, a yearling and a two year old colt of Hambletonian. If Elrod is scarse of horsepower to run the farm I think it will be well to purchase for him two large mares, and let him breed them. They could do full work this year, and by next spring I expect to send 12 or 15 mares from the East….” While the horse “Young Hambletonian” was on the farm, Grant had one of the best trotters in the country. Grant wanted his horses bred to be driven as trotters or bred to produce more fillies that could also be trained and bred. Selling top trotters could bring a good profit when sold to other horse farms. In 1873, Grant’s horses were valued at $25,000. The other animals on the farm, and the equipment, were worth another $11,000. Even though the farm seemed to be producing some very good horses, it barely profited. Grant did not believe that Elrod was keeping a very good account of the records for the property, nor was he keeping Grant informed about issues on the farm. Grant relieved Elrod of his duties in 1873, but Nathaniel Carlin’s management of the farm over the next two years was even worse than Elrod’s. Grant decided to shut down the farm and put its resources to auction in 1875. He lost the farm when he was swindled by a New York City business partner in 1884.

Today, the last ten acres of Grant’s horse farm constitute Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site.

For Further Reading

Brands, H.W. The Man Who Saved the Union: Ulysses S. Grant In War and Peace. Doubleday: New York, 2012.

Grant, Ulysses S. The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant. Edited by John Y. Simon. Vols. 16-25. Southern Illinois University Press: Carbondale and Edwardsville, 1988-2003.

McFeely, William S. Grant: A Biography. W.W. Norton and Company: New York, 1981.