Last updated: August 30, 2022

Article

President Grant's Cold War with Spain

Harper's Weekly/Library of Congress

President Ulysses S. Grant was determined the keep the United States out of a war with any European power during his presidency. The two countries which he faced the greatest prospect for a conflict were Great Britain and Spain. In 1871, his administration successfully worked out an agreement with Great Britain with the ratification of the Treaty of Washington. This treaty brought a successful conclusion to American grievances known as the “Alabama Claims” In which the United States blamed Britain for manufacturing ships used by the Confederacy which caused damages to Union shipping during the US Civil War. The successful resolution of this led to a more productive relationship between the United States and Great Britain. America’s relationship with Spain during Grant’s presidency was a more complicated story.

The major issue in the relationship between the United States and Spain during Grant’s administration involved Cubans struggling for independence from Spanish rule. After longstanding grievances among the Cubans failed to be addressed by the Spanish Empire, revolutionary Cubans erupted in revolt in October of 1868. This revolt would continue throughout Grant’s presidency (1869-77). The Cubans called for three major policy changes: independence from Spain, democratic reforms, and the abolition of slavery. These ideas resonated with a large portion of the American public and money and supplies raised by Americans were sent to help the Cuban revolutionaries. Some Americans even joined the Cuban revolutionaries despite America officially being at peace with Spain. These acts were called filibustering. The challenge for Ulysses S. Grant and his administration was whether to officially support these revolutionaries or not.

The cabinet wrestled with this decision as members split on their course of action. The Cubans fought for ideals which were ideologically close to American ideals (Independence, democracy, and the end of slavery) yet overthrowing Spanish control on the island threatened key US economic trade interests with Spain. Both Secretary of the Interior, Jacob Cox and Postmaster General, John A. J. Creswell supported aid for the Cuban rebels. The strongest voice in favor of Cuba was Secretary of War John A. Rawlings, although it was soon discovered shortly after his 1869 death that he had a financial stake in supporting the Cuban rebels. An important voice on restraint was Secretary of State Hamilton Fish. Fish became engrossed in settling the “Alabama Claims” with Britain and was worried about the hypocrisy of America supporting Cuban rebels while the US was pushing for reparations from Great Britain for its tacit support for the Confederacy in manufacturing ships for use by the Confederacy against Union shipping. Fish felt that intervention would weaken his negotiations with Britain. Grant ordered Secretary Fish to issue a proclamation of neutrality. Yet Spanish heavy-handed methods to put down the Cuban rebellion including executions of some American citizens captured in Cuba, often inflamed American passions and even Grant became exasperated. He remarked, “Not that Spain has not a perfect right to prosecute as vigorous a war as she pleases, upon her own soil, observing the rules of civilized warfare; but that the rights of our citizens have been so wantonly invaded by Spanish troops…that such a course would arouse the sympathies of our citizens in favor of the Cubans to such a degree as to require all our vigilance to prevent them from giving material aid [to the Revolutionaries].”

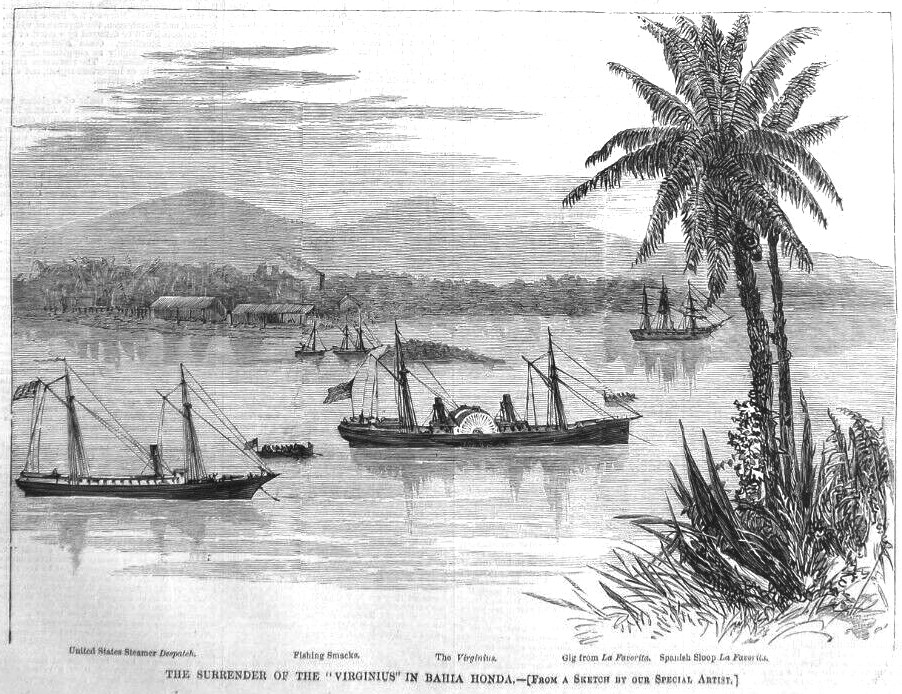

Grant’s neutrality during the Cuban crisis was severely tested by the “Virginius Affair” which brought the United States and Spain to the brink of war. The Virginius was a steamship that started as a Confederate blockade runner during the US Civil War. It was owned by Americans and employed in the Cuban revolutionary cause transporting weapons, supplies and men to aid the revolutionaries against the Spanish. A great majority of the crew were inexperienced seamen and “many of whom did not understand the ship’s true mission.” Spain knew about the ship and endeavored to capture the vessel. In October 1873, the Virginius was captured in waters outside Cuba by a Spanish warship. The Spanish arrested the entire crew and brought them to Cuba to be tried for piracy. One of the leaders of the Revolution, Manuel de Quesada sent a petition to Grant, “the authorities…were about to try the crew and other persons on board the Virginius as pirates…They are sons, brothers, husbands and near relatives, and your Excellency will not wonder, therefore that we as citizens and residents of this country whose chief magistrate you are, apply to you and ask your interference under circumstances of such serious importance.” These pleas for help failed. Spain would succeed in executing fifty-three of the crew including its Captain, Fry. Only the presence of a British warship in the harbor of Santiago, Cuba (the place of Executions) threatening to bombard the city if the executions continue, convinced the Spanish to stop them.

These executions incensed the United States. “Many leading newspapers demanded war against Spain.” Secretary of State Fish, who was a moderate in dealing with Spain, was livid and denounced the executions as, “butchery and murder.” Even prominent Confederate officer, John Mosby offered his military services in event of a war with Spain. Grant, however, maintained a level head and wanted a peaceful resolution. In a letter to Congress on January 5, 1874, Grant laid out his demands. “The restoration of the vessel, [Virginius] the return of the survivors to the protection of the United States, for a salute to the [US] flag, and for the punishment of the offending parties.” When the Spanish captured the Virginius they tore down the US flag. As a result, Grant wanted an assurance from Spain that, “no insult to the flag of the United States had been intended.” Spain agreed to most of Grant’s terms, returning to the US the survivors of the crew and paying an indemnity of $80,000. Grant would later proclaim, “an arrangement which was moderate and just and calculated to cement the good relations which have so long existed between Spain and the United States.”

America would not go to war with Spain over Cuba during the Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant. Yet there were several close calls and the American people had not let go of their desire to free Cuba from Spain. For their part, Spain continued its heavy handiness to oppress Cuban desires for independence. Although Grant succeeded in peaceful means, the United States would later fight a war with Spain that resulted in Cuba’s independence in 1898, thirteen years after the death of Ulysses S. Grant.

Further Reading

Kahan, Paul. The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant. Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme Publishing, LLC, 2018. PP 96-101; 134-137

John Y. Simon, ed., The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume 19: July 1, 1868-October 31, 1869. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1995. pp 234-35

John Y. Simon, ed., The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume 24: 1873. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000. P 245

John Y. Simon, ed., The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume 25: 1874. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2003. pp 4-5