Last updated: June 30, 2022

Article

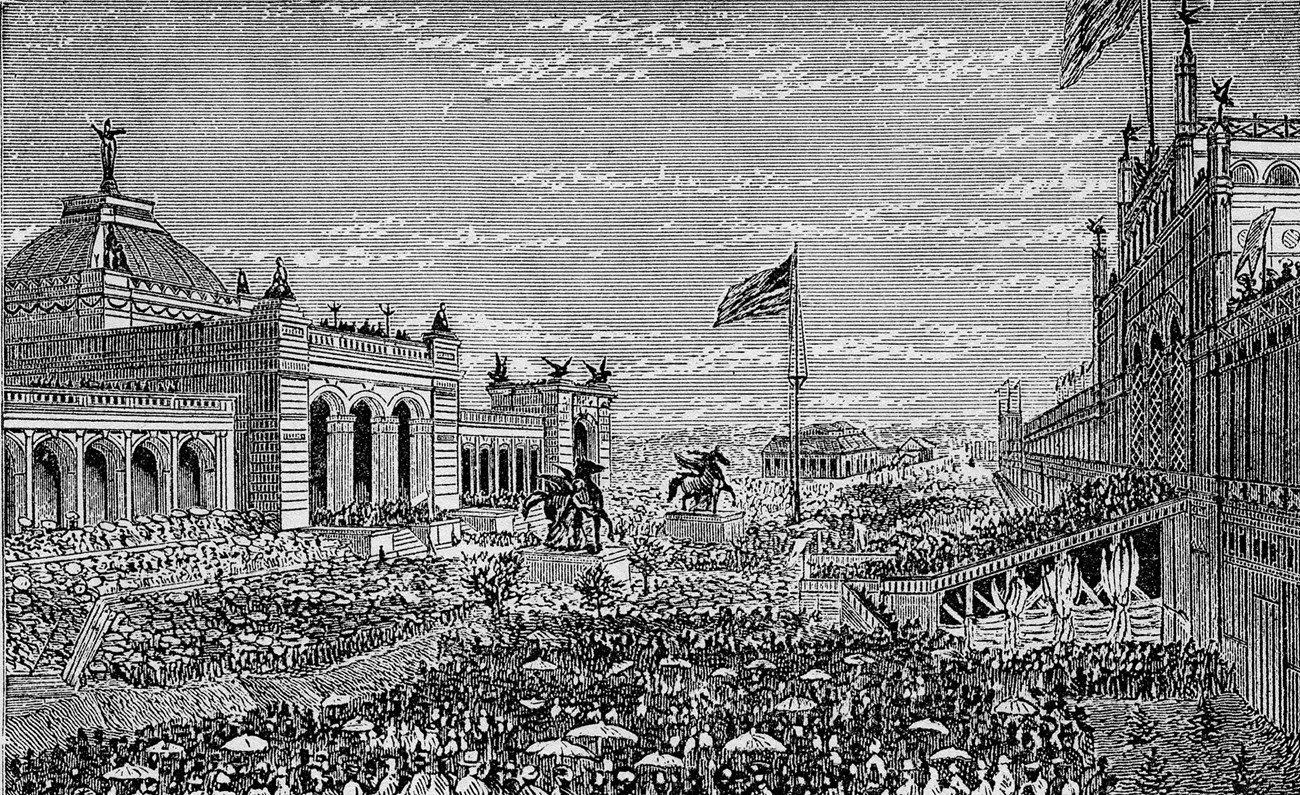

President Grant and the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia

Wikipedia/Public Domain

July 4 has long been celebrated in the United States as Independence Day; however, the date was also significant date in the life of Ulysses S. Grant. On July 4, 1855, Ulysses and Julia Grant’s third child and only daughter was born on the White Haven property. Later, Grant’s famous victory during the Civil War took place on July 4, 1863, when the City of Vicksburg, Mississippi, surrendered to Grant. During his presidency, the nation marked another important July 4th with the Centennial anniversary of the nation gaining its independence.

By 1876 the United States had changed a great deal since its founding. That year, the country had 37 states compared to the original 13. Within a month of the 4th of July, Colorado would enter the union as the 38th state. Despite being just over a decade past the devastating Civil War of 1861-65, the nation was gearing up for celebrations commemorating the centennial of American Independence. President Ulysses S. Grant was nearing the end of his second term in the White House and as President he would have a role in these celebrations. Unfortunately, Grant did not write much about what he was doing during the Centennial. He did respond to a letter from the city council of Birmingham, England, congratulating Grant and the United States on its centennial. Grant expressed his appreciation and the continuing “ties of kindred and interest” between the United States and Great Britain. Thankfully, Grant's wife Julia provides us some insight of their activities during this time in her memoirs.

The celebration of the American Centennial took place throughout the spring and summer of 1876. During this time the Grants were very busy receiving guests and entertaining. Julia recounted that during the opening of the centennial celebrations, the Grants were hosting the Emperor and Empress of Brazil. They then journeyed to Philadelphia, the city where the Declaration of Independence was signed. Here President Grant and the Emperor of Brazil were slated to “open the centennial celebration of America’s independence” by starting the “great Corliss engine.” The Corliss engine was a “specifically built rotative beam engine that powered virtually all the exhibits at the centennial exposition in Philadelphia that year.” Nevertheless, Julia Grant expressed disappointment of not being part of this ceremony. She mentioned that while the Empress of Brazil was allowed to place her hand on the valve which started the engine, she was not. This bitter memory stuck with Julia, who wrote, “I the wife of the President of the United States--I, the wife of General Grant--was there and was not invited to assist at this little ceremony…I wonder what could have prompted this discourtesy to the wife of the President of the United States and at the same time, this honor to the wife of a foreign potentate. She went on to say, “if General Grant had known of this intended slight to his wife, the engine never would have moved with his assistance.”

Meanwhile, during the Centennial the National Women’s Suffrage Association presented a modified version of the “Declaration of Rights of Women.” This document, originally written by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage at Seneca Falls, New York in 1848, was presented to the authorities at the Centennial ceremony in Philadelphia. While the United States Constitution greatly expanded citizenship rights with the 14th amendment and voting rights to African American men with the 15th amendment after the Civil War, Women’s rights to equality and voting were still lacking. The 1876 version of the Declaration of Rights of Women stated, “and now at the close of a hundred years…we declare our faith in the principles of self-government our full equality with man in natural rights; that woman was made for her own happiness, with the absolute right to herself to all the opportunities and advantages life affords for her complete development.” This document concluded, “we ask of our rulers for this hour no special favors, no special privileges, no special legislation. We ask justice, we ask equality, we ask that all the civil and political rights that belong to citizens of the United States, be guaranteed to us and our daughters forever.” It would still take forty-four years for women to earn the right to vote with the ratification of the 19th amendment in 1920.