Last updated: June 12, 2024

Article

Preserving Two ICBM Facilities

Watch a non-audio described version of the presentation on YouTube.

No Lone Zone: Two Preservation Paths In Preserving ICBM Facilities

Presenters: Eric Leonard and Christina Bird

Abstract

One of the most significant strategic weapons in history, the Minuteman was America’s first push-button—literally turn-key—nuclear missile. This marriage of rocketry and nuclear capacity created a weapon for which there was virtually no defense. Once the launch command was given and the keys were turned, a Minuteman missile could deliver its thermonuclear warhead to a Soviet target within a half hour. Solid-fueled intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) such as the Minuteman and Peacekeeper formed the land-based portion of America’s Nuclear Triad throughout much of the Cold War.

ICBM facilities were built in the 1960s and operated by the US Air Force for thirty years. During the nearly ten years the Minuteman system was under construction, the designs of control centers evolved to take advantage of technology and policy changes. This included a second generation solid fuel ICBM, known as the Peacekeeper, which entered service in the 1980s.

The 1991 Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty allowed for the United States and the Soviet Union to preserve “static displays” of once active ICBM facilities for educational purposes. This allowance created a unique preservation path that has resulted in the development of a small number of former Minuteman Missile facilities being converted to static display as museums and national parks.

The first of these was the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site in South Dakota, authorized by Congress in 1999, and established in 2002. The two preserved Delta were considered the best preserved examples of the initial operational character of the Minuteman system. Built as part of the fifth missile field in 1962 and converted to serve the Peacekeeper missile in 1986, the Quebec-01 missile alert facility was decommissioned in 2005. In the summer of 2019 the State of Wyoming will open the Quebec-01 Historic Site.

Designed to execute a nuclear war, these sites present common preservation challenges. This presentation will explore these common challenges and the often unique solutions these have found to address them. These two places have much in common as well as important design and operational differences. Likewise, as preserved museum facilities, the two places share significant similarities and operational differences. As Quebec-01 was been developed, Wyoming State parks staff have worked closely with the staff of the national park to learn from its developmental experience.

Presentation

Eric Leonard: So we're here again today. Just like yesterday, Christina and I are both aware that we're what stands between the room and lunch. So we're going to tell a compelling story to hopefully balance your hungry stomachs. ICBM facilities are, in many respects on the vanguard of US homeland cold war sites and preservation because they're highly visible. They're a focal point for the public to come see. They represent an entry point into much larger discussions and they're an embodiment of the William Faulkner phrase that the past isn't dead, it isn't even past, in that we're preserving facilities that are no longer used but are nearly identical to facilities still in use. 2019 marks a couple of important anniversaries and an opportunity look forward and backward. This year, this fall will be the 20th anniversary of the Parks Minuteman Missile National Historic sites establishment by Congress in 1999. Two weeks ago, Memorial Day weekend, was the 15th anniversary of the first public operations of the park in public tours at the launch control facility at Delta-01.

Probably sometime this month Quebec-01 will open to the public for the first time. So just like the trajectory of a missile, one site is about to blow off the third stage and going to target. The other site is leaving the launch facility. We're going to tag-team this. I'll talk a little bit about the two Delta sites and then Christina will do the same for Quebec-01.

You can't tell the story of a dispersed weapon system completely in just one place. So the Minuteman Missile as a National Park site is in three locations in western South Dakota, about an hour to the east of Rapid City, immediately north of Badlands National Park. All three sites are along Interstate 90 and that's critically important to that site's selection, and then now it's success as a public facility.

We're Minuteman Missile National Historic Site, and we're unusual because we preserve both a control center and a completely intact missile silo launch facility with a missile inside it. That's Delta-09 and its visitor experience here can be frustrating to the uninitiated because for very obvious safety and enclosed space reasons the visitor does not get to go inside the silo because the silo is a very small, confined space. It's 12 feet in diameter in the launch tube, with a 60 foot missile in it. There's just not a lot of space inside the missile. Then fortunately, for us, one of our partners, the South Dakota Air and Space Museum, just outside Ellsworth Air Force Base near Rapid City, if you take the base tour in the summer, the main attraction to that base tour is a preserved launch facility trainer. It's identical to Delta-09 but it has a convenient, two-story stairwell that allows you to walk into it. As long as that's open to the public, we can continue to preserve this completely intact and deflect the pressure to change it so people can go underground.

What we're most famous for is the control center at Delta-01. These two sites were partially picked for preservation because they're early built in 1962, reflecting the original mutually-assured destruction posture. So Delta-01 doesn't ... from the highway, it looks unremarkable, like a large ranch house or a paranoid rancher's house. The underground portion of it is incredibly small. It's, imagine a prairie submarine that if you're staying in this hotel, the control center is smaller than your hotel room. So one of our challenges is, how do you get people in and out of that, a very small facility that was never, it was meant to execute a nuclear deterrence mission, not tourism. Public tours of this facility have been going on now for 15 years. They're limited to six people and we'll explore why that is in a little more detail and the attraction is again, that underground control center.

Christina Bird: I'm a little shorter than Eric. This is Quebec-01. We call it a missile alert facility because our period of significance is actually for the Peacekeeper missile. The Peacekeeper missile was activated in 1986 and deactivated in 2005 and so it is very, very recent history. The Quebec-01 is located approximately 30 miles north of Cheyenne, Wyoming and 30 miles south of Chugwater, Wyoming along Interstate 25. This project really is not only a preservation of the outside resources, the topside facility as well as the capsule facility, but it also is a restoration project and we'll get to that here in a minute. This is the helipad over at Quebec-01 and it looks like it's standing out in the middle of the prairie, but the site was chosen very specifically because just over this rise sits Interstate 25. We're about a quarter mile off of the Interstate.

This is the 400th Squadron. This is the Peacekeeper Squadron. Peacekeeper is unique in national and global history in that it is the, this is the only place southeast Wyoming, was the only place that Peacekeeper was housed. The Peacekeeper 400th Squadron included Quebec, Papa, Romeo, Sierra and Tango flights. You can see Quebec-01 right here is the missile alert control facility for all of Quebec missiles as well as helping to monitor all of the other missiles in the flights. Peacekeeper was one of the most accurately destructive missiles ever created by the United States Air Force. It could house up to 10 independently targeted warheads and so it really was one of the larger missiles and they were placed inside of Minuteman-01 and Minuteman-02 silos. So instead of rebuilding the silos at all of these locations, they simply modified the silo and placed the Peacekeeper missile inside.

Oh, oh. We got stuck. The Squadron Patch for the 400th shows the 10 reentry streaks coming back down to Earth. This is the Morale patch for the 400th, reminiscent of the Jolly Roger, the bombing squadron from World War II, except we have replaced these with nuclear weapons. Oh, come on. This is some of the original wall art inside the capsule. Quebec-01 was known as the showplace of the 90th because it was the closest missile alert facility to F.E. Warren Air Force base and so it really is only 30 minutes away from the air force base. That's where the VIPs were all brought to tour the sites. So the only 30 minutes out both alludes to its distance to F.E. Warren Air Force Base as well as calculated flight. So it had a double meaning for folks who visited the site.

Eric Leonard: The preservation story of these sites, especially the Minuteman sites begins in 1991 with the signing of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty by the United States and the Soviet Union. Tucked into a thousand-page treaty are single sentences that allow for highly regulated static display of launch facilities, launch control facilities. Then there's a confluence ... in 1992, the teenage son of the Superintendent at Badlands National Park, seeing the news of the dismantlement of the missile field in South Dakota, looked at his Dad and said, "Man, the Park Service ought to have one of those." Coupled with the treaty, by 1993 the sites are already selected and the Park Service and the Air Force are working together to preserve these places.

The Defense Legacy Program was critical to allowing that early work to take place. There's a historic engineering record documentation conducted between 1992 and 1995. In 1995 the Air Force and the National Parks Service published a special resource study that lays the groundwork for the present-day park and then a little time passes and finally in the fall of 1999, the park is authorized. Then a little time passes where some modifications are done to the silo following the installation of a training missile in the silo, and making Delta-09 one of only two places in America where the public can walk to the barrel of nuclear Armageddon and look down at the loaded gun. The other being the Titan Missile Museum in Arizona. That official start of the park is September, 2002 when the Air Force handed over the site to the National Park Service and in the next year you had a Park Service staff established.

Christina Bird: There are various treaties that would both end the Peacekeeper system in the Air Force and be the vehicle to begin the Section 106 process for Wyoming State Parks and our Wyoming SHPO. In order to preserve one of the Peacekeeper missile alert facilities, there was a programmatic agreement written between the Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office and F.E. Warren Air Force Base with several amendments that would allow us to preserve one site. Unfortunately, Quebec-01 will never have a silo. We were not allowed a silo as per the latest treaty and so the only thing that we will be able to preserve in the Peacekeeper story is a missile alert facility. The land conveyance was signed by President Trump on December 12, 2017 and that authorized the Air Force to be able to transfer the property after the Wyoming State legislature had spent some time being able to negotiate. They have a bill being able to negotiate and provide funding for startup and construction at the site.

Eric Leonard: Following the formal establishment of the park, planning began in earnest with a general management plan completed in 2009 that we physically are finishing all of the infrastructure design, envisioned in that time this year. In 2010 we did a historic structure report, cultural landscape report. Our treatment options at the two Delta sites are slightly different. We were intending to preserve and restore a Delta-01 to a ready alert status that reflects its final years of operation between 1990 and 1993. Per that Start One treaty at Delta Nine, our intent is not to preserve a missile ready to go because then the public couldn't see through the glass and that glass enclosure is actually designed to meet treaty requirements to allow Russian overflight verification that the missile is in place and modified for display purposes and cannot ever be used. Our historic structure report, it's only about 10 years old, and we're starting to understand some perhaps unintentional oversights within that document.

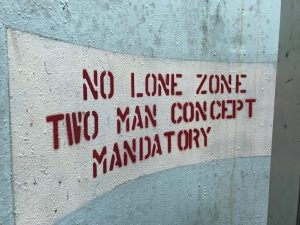

The visitor experience at Delta-09 is strictly above ground and yet Delta-09 has features that are 10 to 15 feet underground, 30 to 40 feet underground and then going all the way to 80 feet underground. The historic structure report ignores anything that is not a surface feature and that's a potential serious challenge that we are working to address because if you don't take care of the stuff underground, that's going to have serious consequences down the road. One of the things that was done last year through our general management plan ... again, this contradiction, we're preserving things the public was never intended to see. The Air Force did not design these as this user-friendly facilities and even today visitors will drive up and become very uncomfortable because along the fence compound are signs that read Use of Deadly Force Authorized.

There's no visitor parking. So last year at both Delta sites, a respectful distance away from each of them, we constructed visitor parking with RV large vehicle turnarounds because in the summer that's a fairly significant part of our business. Then restrooms, because visitors need that and these facilities will allow quite frankly, a significant increase in visitation in summer that we don't yet really understand how much that will be, but it's going to be more people.

Christina Bird: So as Eric showed you earlier in some of his pictures, you saw the capsule at Eric's site, the Minuteman National Park site. In 2005 when the Peacekeeper we just decommissioned, the Air Force came in and stripped out all of the equipment at the Quebec-01 missile alert facility. So this is where I say to you that this is both a preservation project, but it really is a large amount of a restoration project. This is what the capsule looked like when we started, when the Air Force started in approximately 2010-2012. All of the racks had been stripped out. All of the drawers had been stripped out. There's no Deputy Commander's console. There wasn't even restroom facility in the capsule, which would have been original to the capsule. You can however, see that the one thing that did get left was the Commander's console in the back of the capsule.

So it's the Historic Structures report that the Air Force commissions in 2013 that really helps both the Air Force and Wyoming State Parks understand what kind of agreement we're going to come to bring the site back to life. The agreement was is that the Air Force would bring it back to life with all of the equipment that we would need to turn it into a viable historic site for the State of Wyoming. We started working with several of our community partners. We were required to work with Laramie County Planning and Development to do a site plan for the site because we do have to incorporate new parking areas. The new parking areas that we have to incorporate, just to orient you, this is the site back here.

We did not want parking of our visitor on-site and so we had to create parking along our access roads. One of the constrictions to this plan is that we only have, we only own the property from the beginning of the access road to the site and a little bit on either side. So that really did restrict what we could do as far as parking. It's one of the areas that we are fully well aware of that will be underdeveloped for the visitation that we're hoping to get. At the same time, we start work on an interpretive plan, which helps us with our themes and interpretation for the sites. We started working on exhibit plans with a consultant out of Boulder, Colorado, Studio Tectonics as well as interpretive panels. Those interpretive panels are scheduled to be set into production starting next week.

Eric Leonard: The Delta sites were mothballed by the Air Force, following a modified procedure allowing for them to be preserved and that really focused on, obviously the top-secret crypto was removed. Anything that the Air Force could ... internal components that they could reuse were removed, especially from the control center and then certain critical systems were mothballed, however, leaving a number in place, including the original 1962, 3000 foot well. In 2001 the Air Force installed a security system and fire suppression system leading that structure to the original pump system and wiring system that included a waterline going through an electrical panel. By 2015 that system did not want to work because it was a Frankenstein's monster and two years ago we were fortunate in that we pulled that out.

So this room today, everything that's above the red pump is gone except for those two white original water lines. One of our challenges, we're using original heating and cooling systems including a 1960s boiler for heat. At some point, we want to mothball that because in our National Register nomination, one of the things that's true of all of these places, one category is history. The other category, the more significant one in terms of preservation, is engineering. The engineering of these places is really remarkable and an important story to tell. The first tours in 2004, the entire year of the first public tours, the tour of the control center was somewhat misleading because the public was not allowed to go underground.

The park had to execute a series of modifications, safety protocols to address life safety issues because the people using the underground control center were highly trained. They knew where all the risk was. The public doesn't. So above the elevator, we placed a safety gate. In the walkway from the tunnel inside the blast door to the control center itself and similar safety gates were installed. We also restrict tours to six people per tour, the elevator cars, three feet by five feet and we put with a capacity of about 2000 pounds. We put a Park Ranger and six members of the public on that for tours. Then, just the nature of the place, the Air Force essentially, when the last alerts were called, the Air Force locked the doors and walked away. So Delta-01 is a time capsule of its very last years. It is an artifact-rich environment, and the artifacts are, they're mundane and sometimes just crazy making.

In the linen closet it's out of frame, but there's a mouse trap. The mops are artifacts. You can just see it on the edge there. There's a cutoff of a gallon jug that says Do Not Throw Away. It was used for some kind of cleaning procedure and this, these were ... the room feels ordinary and it is, but it's extraordinary. It tells a really important component of the deterrence mission and how it was supported by the Air Force. In the security office as one example, we have paper objects everywhere in this building, many of which are have been for 25 years, exposed to light and that's something we're acutely aware of and have a project in to take those objects out, scan them, replace them, and get the originals out of sight. If by scanning we'd make all of that documentation much more available to the public. Right now it's in there. They don't necessarily see it.

Christina Bird: This is Quebec-01 as we saw it very early on in 2012. Windows boarded up. They had had an incident where a vandal came in and stripped all the copper, between 2005 and in 2010. So we, this is the starting point for us. When we first started at the site there was no electricity, there was no electricity. We're doing site criteria’s in a building that is 30 miles north of Cheyenne, Wyoming. It's got no electricity. It was the middle of winter and it had no restroom facilities. So we were taking groups of legislators, we were taking groups of folks out to the site at this time. Every time we went, the Air Force had to do air quality controls, air quality testing, in the capsule. There was no electricity, so no elevator. So we all had to climb three sets of ladders down to the capsule.

This is the mechanical room. Same as you would find at Delta-01, only the Air Force stripped out all of our original equipment. So what we are doing, preservation of the outer structures, we can only do what we can do with what we've got. It turned out to be a blessing in disguise as I've had many discussions with Eric about his systems that are vintage 1962. This is the security office. This is the launch equipment building. The launch equipment building was stripped of everything usable in the missile field and so the task at hand was to try to put it all back. The tunnel junction, then the capsule, and the capsule really did need a whole lot of love. Middle way through the project, you can see the building. The building is going to be preserved as it is and probably won't even be painted before it's turned over.

This is the topside facility security office, looking at the elevator. We also have a vintage 1962 elevator, a little bit larger than Eric's, and a little bit larger than Rob's back in the back. Then capsule midway through. This is the capsule midway through the process. Deputy Commander's console, which you can see is missing the absolutely valuable red code safe and the launch enable switches. This is Quebec-01 as of two weeks ago. The Air Force has worked very, very hard to try to put it back in place to 2005, including some of the furniture, including the pool table, furnishings in the bedrooms, security office, launch equipment buildings. We've gotten back generators. Thank goodness that we've gotten those back as well.

Then the capsule and we've been working very, very hard to try to get original equipment back from Quebec-01 and we're very lucky in that Cheyenne, Wyoming happens to be a haven for people who retire for the military. So we've gotten several of our actual artifacts back, including the Commander's chair from Quebec-01. So we're really, really thrilled about that possibility. We are also really excited to report that we will have the title to Quebec-01 this week and we will be beginning our process to get our exhibits installed.

Eric Leonard: What we presented today is just two stories of a group, a smaller group of sites and we're very fortunate. I want to acknowledge that we're joined today by David Grisdale who works at Whiteman Air Force Base, preserving Oscar-01 and then Rob Branting, who works for the North Dakota Historical Society and manages the Ronald Reagan Minuteman Missile State Historic Site. But the math is Oscar-0 and as the song says, the cold war in 1980 song by Timbuk 3, the future's so bright, we have to wear shades. There's a lot of promise in the work that's being done at these places and there's a lot of interesting and demand in these sites. One of the things that the four of us talk about ... Rob gets a lot of business by people who try to get to Delta-01 and in the summer, those control center tours are booked eight weeks in advance. So he gets business because people can't get into my place and that kind of mutual support is really important in what we do. Thank you very much and if there's time for questions we'll entertain them.

Questions

Mary Striegel: We have time for two questions.

Eric Leonard: All right.

Mary Striegel: Who has the first question? Here we go.

Speaker 1: So you know for a fact that there's some airman somewhere who is just mad, cussing you guys because he had to pull all that stuff out of there and now he's got to put it right back in again. That's my comment.

Christina Bird: Let's hope so and let's hope he brings the originals back.

Mary Striegel: Next question?

Speaker 2: Having spent all my favorite childhood holidays at launch control facilities visiting my Dad, do you have any oral history programs starting, talking to the airmen or the families that spent time in these facilities?

Eric Leonard: As the longer side, we have oral history. Our oral history program began as the park was authorized in 1999 so we have about 100 oral history interviews and we're acutely aware that our window of opportunity is now and that's trying to find resources to do additional interviews is really important. Last year we finished a two-year project that gained us another 40 interviews and we're still working to make those available on the Park's website because there's a wealth of information in those that connects to a wide variety of stories. Ask me later about Vice-President Dick Cheney's interview.

Christina Bird: As far as Quebec-01 is concerned, our priority right now is of course, getting the site open to the public. We do have an opportunity on our website for Wyoming State Parks to offer your thoughts, your experiences at Quebec-01 in the 400th Missile Squadron or at F.E. Warren Air Force Base. The next step for those is to contact those people and get oral interviews. We have a little bit of luxury in that Peacekeeper deactivation in 2005, if you're in your early twenties still offers me a little bit of time to get to you.

Speaker Bios

Eric Leonard has worked for the National Park Service since 1995 at nine parks in seven states. A practicing public historian, Eric has served as Superintendent of Minuteman Missile National Historic Site since February 2015.

Christina Bird has spent over twenty years in the museum field and has been with Wyoming State Parks, Historic Sites and Trails since 2010. She currently serves as District Manager, overseeing day to day operations at Quebec 01, the Wyoming Historic Governors’ Mansion as well as overseeing staffing at Wyoming Territorial Prison and Curt Gowdy State Park.

Read other articles from this symposium, Preserving U.S. Military Heritage World War II to the Cold War, or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.