Last updated: August 15, 2022

Article

Prelude to Gettysburg: The Battle of Brandy Station

“A battle so fierce that friends and foes knew not who they fought, or behind which banner they charged.”[1]

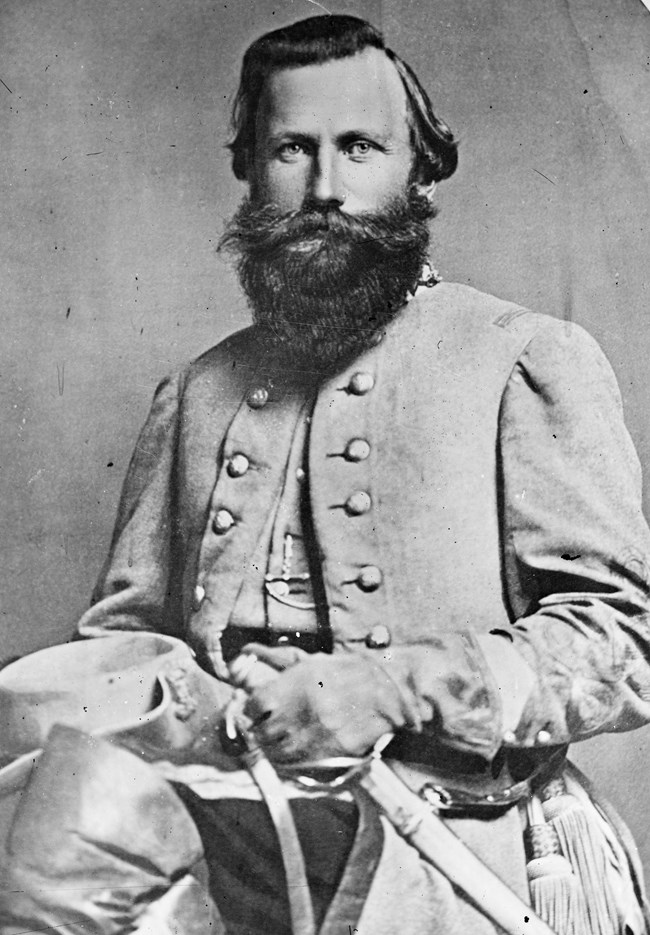

These are some of the words spoken at the dedication ceremony for the Pennsylvania memorial erected in the National Cemetery in Culpeper, Virginia, recalling the great struggle that had taken place there during the Battle of Brandy Station. Unknown to both sides, the Battle of Brandy Station fought on June 9, 1863, would be the largest cavalry engagement ever fought on the North American continent. It was said by one of the aides to Confederate Major General J.E.B. Stuart that “Brandy Station made the Federal cavalry.”[2]

Library of Congress

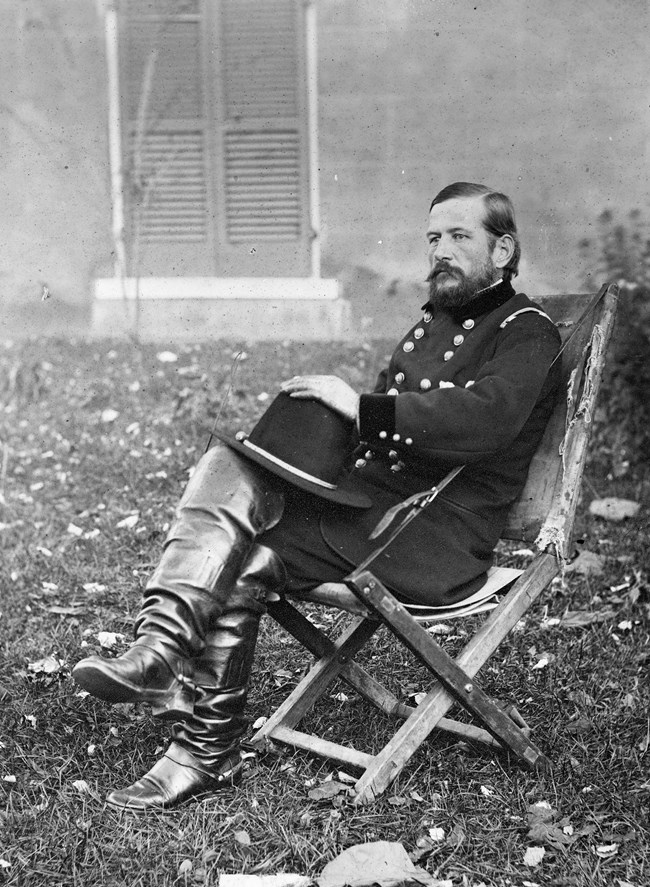

By late spring of 1863, the cavalry branch of the Army of Northern Virginia was practically untouchable by Federal troopers. Previously, the United States cavalry was spread out with no central command system. After Major General Joseph Hooker took command of the Army of the Potomac in January of 1863, he reorganized the army, including the cavalry branch. This culminated in the creation of a separate cavalry corps composed of three divisions. After the Chancellorsville Campaign Hooker chose General Alfred Pleasonton to relieve General George Stoneman of the Cavalry Corps command. Pleasonton was a seasoned cavalier who had fought Mexicans, Native Americans, guerillas in Kansas, and Confederates before his appointment to corps command. He showed skill and courage during the Peninsula Campaign. This experience and a knack for self-promotion impressed his superiors. Under his command he had many able-bodied subordinates including Brigadier General David M. Gregg, and a man who would become a well-known figure at the Battle of Gettysburg, Brigadier General John Buford.

The reorganization was an effort to even the playing field against Stuart’s vaunted cavalry, and helped to create an esprit de corps amongst the horsemen of the cavalry corps. Jeb Stuart was Robert E Lee’s eyes and ears and the Army of Northern Virginia’s cavalry commander who had successfully out matched his opponent continually in the field of battle during the first two years of war. The men of the US Cavalry Corps were now eager for a fight and ready for the campaign season.

The Federal Cavalry Corps’ adversaries in the Army of Northern Virginia were also feeling confident and well prepared for the coming campaign. After their victories at Fredericksburg in December of 1862, and Chancellorsville earlier that spring, the Confederate cavalry under Stuart felt unbeatable. It was at its zenith in terms of numbers, preparedness, and confidence. As Robert E. Lee made his plans to march north, he moved his cavalry to Culpeper County, a region with foraging opportunities and strategic value. Here General Stuart would plan and execute three “Grand Reviews” of his cavalry corps, massing some 11,000 horsemen in the plains of Culpeper. On the evening of June 8th after the final review, Stuart sent orders to his brigades to camp within a few miles of Brandy Station and the Rappahannock River. The plan was for them to cross the river the next morning, screening Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia’s march north.[3]

Library of Congress

Only two weeks after taking command of the Federal cavalry, Pleasonton would be leading his troopers across the Rappahannock River in the opposite direction that same morning to strike Stuart and his veteran horsemen. Reports had come to US headquarters, in part due to the Grand Reviews, that the cavalry of the Army of Northern Virginia was massing in Culpeper County. It was believed by the command staff of the Army of the Potomac that either Stuart meant to make another large-scale raid, or the cavalry corps was the vanguard for another invasion by Robert E. Lee into Northern territory. To combat this move, General Hooker dispatched Pleasonton and his cavalry, to “disperse and destroy the rebel force assembled in Culpeper.”[4] The plan was to divide the Federal force in two and simultaneously cross the Rappahannock River with some 8,000 cavalry, 3,000 Infantry, and 34 pieces of artillery, surprising and if possible, destroying the Confederate cavalry at Brandy Station.

Hundreds of pages have been written about the ensuing engagement across the rolling terrain between Brandy Station and the Rappahannock. This post will focus on the actions of two of the commanders at Brandy Station who would have their names forever connected to the upcoming Battle of Gettysburg, one famously and one perhaps infamously; United Sates division commander John Buford and Confederate corps commander J.E.B. Stuart.

Command of the right wing of the Federal cavalry corps was given to the capable Brigadier General John Buford. This veteran trooper was respected and admired by his men, one going on to say, “it was always reassuring to see him in the saddle when there was any chance of a good fight.”[5] Buford led his 6,000 men across the Rappahannock at Beverly’s Ford early on the morning of June 9, 1863. Being the wing commander, Buford’s division command fell to Colonel Benjamin Franklin “Grimes” Davis, his First Brigade commander, who also continued to lead his brigade during the morning’s battle. Two Confederate pickets of the 6th Virginia cavalry spotted the Federal column crossing the river and quickly fell back to their picket reserve. The first shots of the Battle of Brandy Station were between this 30-man picket reserve of the 6th Virginia and the vanguard of the Federal right wing, the 8th New York cavalry. The pickets caused the Federal advance to pause and deploy skirmishers and then retreated two miles back to the main body of their brigade.

Library of Congress

Several miles away on Fleetwood Hill General Stuart awoke to the sounds of gunfire in the distance. The US cavalry took him by surprise and before the day had begun the renowned Stuart had already made several mistakes. The night before he failed to post an early warning skirmish line of troopers on the north side of the Rappahannock. Another problem was the location of the division’s horse artillery. Other than a couple of pickets at the ford itself, the horse artillery was the closest unit of the division and left unsupported only a mile and a half from where the Federal troopers were crossing. Luckily for these men, Stuart responded quickly as he sought to find out what was happening on the Beverly Ford Road. He assembled the scattered brigades of his division, and looked for defensible ground.

Stuart’s first action was to send messages to his brigade commanders, Wade Hampton and W.H.F. “Rooney” Lee, to ride to the sound of the guns while General William “Grumble” Jones and his brigade deployed on the Beverly Ford Road to check the advance of the Federal horsemen. The US troopers of the 8th New York and 8th Illinois, led by Col. Davis, pressed forward toward the Confederate line of artillery as they made their way up the road from the ford. Just as the guns were about to be overwhelmed, the 6th Virginia cavalry followed by the 7th smashed into the advancing New Yorkers. A melee ensued between the troopers resulting in the withdrawal of the 8th New York and the fatal wounding of Grimes Davis.

As the 8th Illinois checked the Confederate counterattack, Buford was left with a command gap at the division level. With the wounding of Davis, he sought out his Second Brigade commander, Colonel Thomas Devin to take command of the division. A replacement in commanders for both of the division’s brigades then ensued. In two hours of fighting, Buford and his men had made it about one mile into Culpeper County. The Confederate force was giving way, but Buford needed time to reorganize his men and make a plan of attack. After a large clash of cavalry on the St. James Plateau, the Confederates again fell back. Soon Confederate reinforcements arrived and deployed in a line of battle. As two of Buford’s regiments attempted to clear Confederate cavalry from the woods in front of them, they quickly found themselves out numbered and facing this deployed artillery and fresh Confederate cavalry.

Buford quickly realized that he could not take the position held by the Confederate forces at St. James Church. This failure scuttled the battle plan to link up with the other wing of the corps under the command of General Gregg. Buford devised an alternate plan to swing around with half of his force and strike the left flank of Stuart’s cavalry. Over the next four hours, Buford and his men slowly pushed back Rooney Lee and his brigade as they tried to hold on to Yew Ridge and the left flank of Stuart’s line.

Library of Congress

As the Federal horsemen pushed through fields, fences, knolls, and stone walls, Lee’s Confederates grudgingly fell back to the northern end of Fleetwood Hill. By now, Devin had observed the Confederate defenders melt away to his front. This was a result of Stuart’s adept shifting of troops in response to the arrival of David Gregg and his troopers from Kelly’s Ford in Stuart’s rear. Buford led his men again in a push for Fleetwood Hill, claiming that he reached the crest and could see Brandy Station in the distance. But soon after, Rooney Lee mounted a counter charge to take back the hill and after a prolonged melee on horseback, the Federal troopers gave way.

By mid-afternoon man and beast on both sides were exhausted and Buford was unable to break the Confederate line. Pleasonton sent orders for Buford and his men to fall back. The fighting on the other side of the hill was both desperate and bloody and produced a similar effect to that of Buford’s efforts. General Stuart, while caught off guard and initially surprised, responded well to the situation and skillfully maneuvered his troops to defend the position and thwart Pleasonton’s plan. Not only with the advance by Buford to the west but also checking the advance of General Gregg in the rear. Later in the afternoon Gregg sent reports to Pleasonton that Confederate infantry were arriving by train close to Brandy Station and that his division was all used up. Without fresh troops Pleasonton decided to fall back across the river to fight another day, but the lack of a Confederate pursuit showed that they were similarly used up and tired from the days fighting.

The Battle of Brandy Station was a slim Confederate victory, as they remained in possession the of the field at the end of the day. However, the Federal cavalry felt pride having proved themselves equal to their Confederate counterparts. For now, the fighting was over, but these same men would once again find themselves in heated combat on the fields and ridgelines of Gettysburg just weeks later.