Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Potential Future Uses for Laser Scanning Data Collected in Carlsbad Caverns

National Center for Preservation Technology and Training

This presentation, transcript, and video are of the Texas Cultural Landscape Symposium, February 23-26, 2020, Waco, TX. Watch a non-audio described version of this presentation on YouTube.

National Park Service

Erin Gearty: Okay, so I&'m going to wrap things up a little bit, talking about where we&'re going with this data set from here. Julie McGilvrey mentioned sort of how this project began, really as a mitigation project, but one of the great things that this project has allowed us to do is to see the built environment within the cave as historic resources.

And so that we&'re going to be able to treat those resources that way. And I think that&'s really important. It&'s also, as top picture, is a picture of our cultural landscape and historic district above ground that sits right above the cave. It&'s going to really let us connect those two, the historic districts above ground and below ground. And really, be able to allow us to tell the d scanning (TLS) data for creative analysis, precise measurements, maneuvering through and understanding complex and challenging landscapes, and pushing the boundaries of cultural landscape analysis and documentation.

The possible application of the TLS data for Carlsbad Caverns National Park are also wide and varied. The park decided to capture TLS data for the underground cultural landscape inventory (CLI), precisely because the data could have broader use beyond this initial project. And really, nearly every work group in the park could utilize this dataset.

The data, for example, will be used to make important management and facility maintenance decisions within the cave. The TLS data is critically important for the upcoming cultural landscape report (CLR) that Julie McGilvrey mentioned earlier. It's going to provide necessary treatment recommendations within the cave, and these recommendations must help us protect the historic resources, while also not jeopardizing the ecosystem of the cave. This is a really complex interaction between the natural and cultural features of this cultural landscape. Sometimes they're actually competing with one another so having this really robust data are going to be really important for us, moving forward.

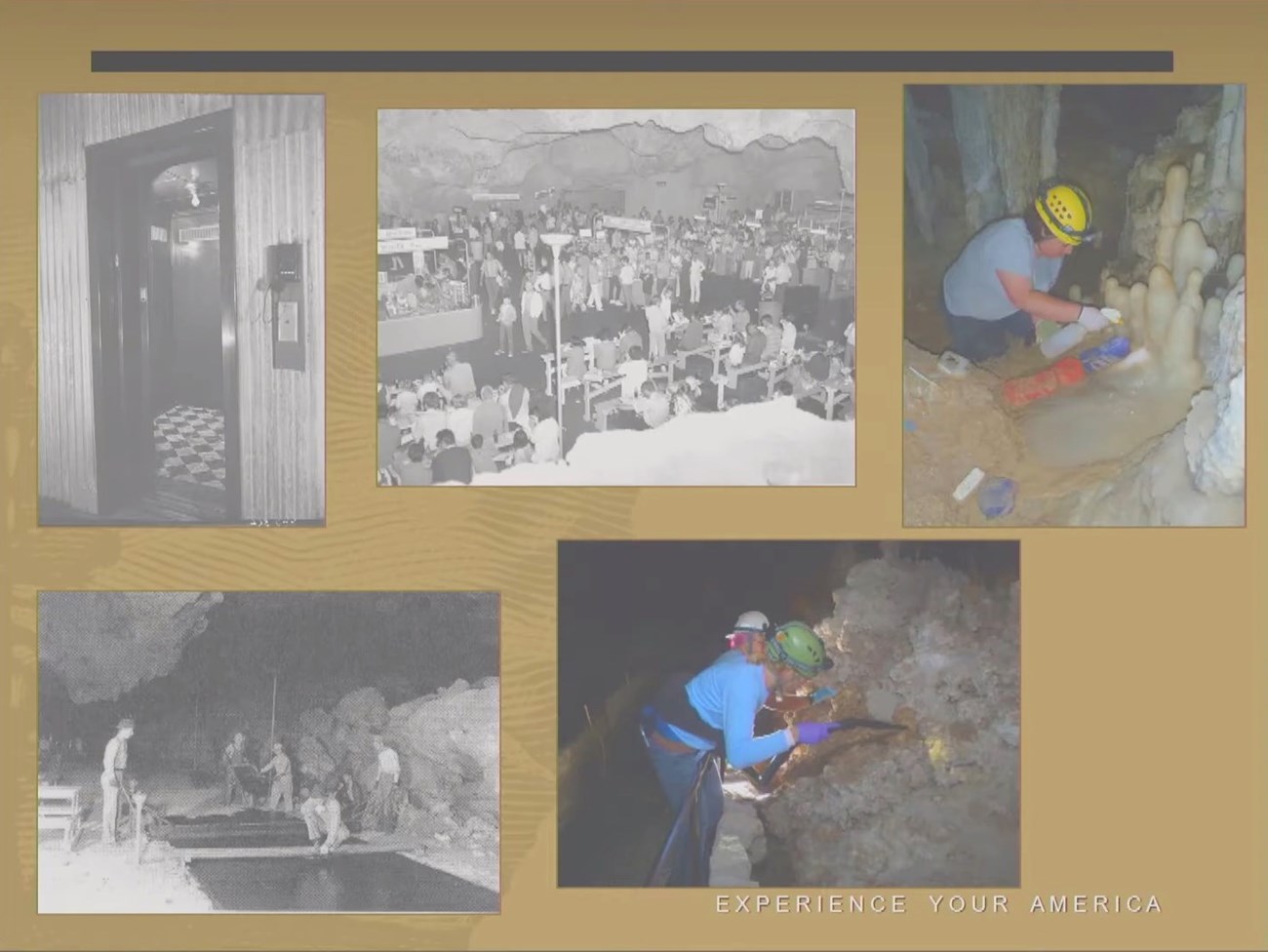

Then also, the data are going to help us with some other studies. We're starting a visitor use management study, so using the TLS data for that, is going to be really important. And so these are just some photos of some of the development with inside the cave, some of the building of the built environment, but then also the two photos on the right will be useful for our visitor understanding with our visitor use management study, things like lint accumulation, that's the bottom. The bottom right one is removing lint that accumulates just from visitor traffic walking down inside the cave. And then the one on the right is, removing some of the algae that grows around the lighting system, especially near pools and wet areas.

An additional potential use of the TLS data relates to public education and outreach. I think it's pretty clear that there's some really good potential there. The Point Cloud could provide a rich interactive experience for the public. I mean we just saw with Malcolm's presentation how great this could be. It could allow the public to learn about the park, both in person and remotely. The data can provide access to the cave when physical presence isn't possible, and it can really enrich the experience of visiting the cave by allowing the public to explore it in a way that's not possible in person, and I think Claire Goreman provided a good example of that.

National Park Service

These experiences can ultimately increase public awareness, knowledge and support for preserving this world heritage site. Importantly, the dataset also contains untapped research opportunities. As discussed, the environment of the cave is conducive to accurate TLS measurements. Additionally, TLS permits access to otherwise challenging or inaccessible locations. These conditions ultimately allow for a reduced impact to cave features, while also generating accurate data. Things like enhanced cave mapping, various forms of monitoring, locating specific features such as algae growth and geologic analysis, are just a few examples of research opportunities that we could use moving forward. I really like these two photos here because the on the left is a historic photo and then the one on the right is the same location, but that's using the LiDAR data set. Pretty amazing, the resolution that we've gotten.

Kimball Erdman showed some of the early maps too, and so this is one of the hand drawn maps. And a really, really great map, but just the resolution that we get with the LiDAR dataset, that same location. Just that enhanced level of detail is really amazing. Beyond Carlsbad Caverns National Park, this project is important, more broadly, for the park service, I think, as a whole. As more parks elect to gather three-dimensional data, there are considerations that the agency should begin to examine. These factors include cost, data processing, data management, storage, training, software, data usage and data sensitivity, and security. Even though the techniques used to generate three-dimensional data are rapidly expanding, and they provide valuable opportunities for documenting cultural resources, these techniques should be employed thoughtfully and carefully.

National Park Service

Three important factors to consider prior to collecting three-dimensional data include data processing, data management and data storage. These data sets, especially those generated through TLS, are large and require dedicated time, expertise and equipment to process, manipulate, analyze and store. These data sets require training and concerted effort to understand and operate the software. In the absence of these requirements, connections with partners are essential, that's why it's been so great to have really great partners with this project.

Parks should understand at the outset how they're going to access and use the data. If three-dimensional data has only one intended product or isn't going to be used long term, TLS may not be a cost-effective option. Using three-dimensional datasets for cultural landscapes projects is an exciting prospect that can greatly expand our analysis and understanding of a cultural landscape, but if we don't consider future data use and management at the beginning of the project, we may fail to realize the many opportunities inherent in these datasets.

While conducting this project, Carlsbad Caverns National Park, we realized that we would need to begin to think about the repercussions of collecting three-dimensional data as it relates to data sensitivity and security. Because cultural resources and areas within caves may contain sensitive information protected by federal law, we would need to understand how we would use the data to ensure protection of sensitive information. This is important for products that are developed for public consumption or by parties with special use permits generating three-dimensional data for private or commercial use. It may not be appropriate to present or allow collection of high definition three-dimensional data if it will reveal sensitive information. There are varied ways to regulate high definition data collection, but I think the important thing is to consider data security at the outset of a project.

I'll just end by saying that the potential for using three-dimensional data to analyze cultural landscapes, there's many factors that we should consider when embarking on these types of projects. But because there is a community of practitioners in this field who can serve as partners and advisors, it's important to reach out because I think you can have some really amazing projects when you have lots of different collaborators.

Thank you.

National Park Service

Speaker Bio

Erin Gearty is the Cultural Resources Program Manager at Carlsbad Caverns National Park where she oversees archeological surveys and research, museum and archival collections, and cultural landscapes and historic districts. Erin works to build relationships with many partners including researchers and universities, Native American tribal partners, park staff, and other parks. She received her Masters degree in anthropology from Northern Arizona University.