Part of a series of articles titled National Register and National Historic Landmarks Celebrate Jewish Heritage Month.

Article

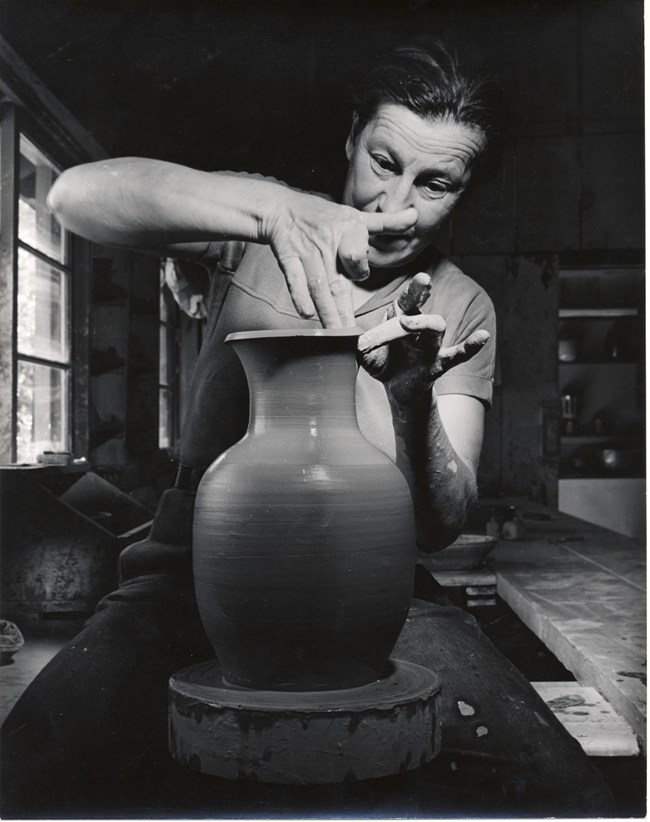

Marguerite Wildenhain, a Life of Renewal at Pond Farm Pottery

Photo courtesy of Birgit Nielsen.

Photo by Otto Hagel, © 1998 Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona Foundation

Early Training

Marguerite was born in 1896 in Lyon, France, to a British mother and German Jewish father. She was brought up speaking three languages because her father wanted her and her siblings to be citizens of the world, rather than of one nationality only.1 Indeed, in her lifetime she lived in five countries, visited many more, and traveled to at least 47 of the 50 states in the United States.2 In 1919, soon after deciding that she wanted to become a potter, she saw a proclamation advertising the new Bauhaus workshops.The Bauhaus was founded at a pivotal time in Marguerite’s young life. The German school of design combined hands-on craft training with fine art instruction. A response to the Industrial Revolution’s widespread mechanization, it emphasized the need to resist lifeless, mass-produced commodities. Its founder, Walter Gropius, sought to reform art education to help artists and craftspeople establish themselves in the new modern world without sacrificing their commitment to art.3 To achieve this, each Bauhaus workshop had two masters, one dedicated to teaching technical craft skills and one dedicated to artistic form. Each object – a building, a tea set, a tapestry – must have an artistic as well as functional value and be skillfully crafted.4

Photo by Otto Hagel, 1950s. © 1998 Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona Foundation

The Bauhaus became a target in the rapidly shifting political climate of pre-war Germany. As more right-wing groups were elected, the art school’s funding was slashed. After Adolf Hitler was elected Chancellor in 1933, the school was raided and closed by the police, acting on orders from the new Nazi government. Though the Bauhaus school only lasted 14 years, the movement had a huge influence on modern design. Its teachings lived on through the work of its exiled students.

Fleeing Germany

During the 1940s, Jewish artists fleeing Nazi Europe brought new artistic techniques and theories to the United States. Marguerite and her husband, Frans Wildenhain, first fled Germany for Holland in 1933. “Everywhere schools were being purged of so-called ‘non-Aryan teachers,’” she recounted, “until one day the mayor [of Halle, Germany] came to me, and with tears in his eyes, asked if I would do the painful favor to resign. I was the only Jewish teacher…. I did not hesitate one minute and left the next day.”6 Frans and Marguerite started their lives over in Holland, opening the Het Kruikje (Little Jug) pottery studio. After seven years, Marguerite fled the Nazi invasion of the Netherlands in May 1940, this time to the United States.By the 1940s, the U.S. established quotas on Jewish immigration and required applicants to sign moral affidavits. American consulates in Nazi-occupied countries shut down, ending the hope of Jewish immigration. French-born Marguerite was able to immigrate in 1940, but her German husband could not. He was drafted into the German Army in 1943 and would not be able to join Marguerite for another four years.

Courtesy the Smithsonian Institute of American Art

Pond Farm

Now in the United States, Marguerite set out to find a place for her husband to teach, a requirement for his eventual immigration. Shefound a position for him at the California College of the Arts in Oakland, where she taught in his place for two years. She came to dislike American academic art education, believing that it valued degrees over true mastery of skill.In 1942, Marguerite accepted an invitation from friends Jane and Gordon Herr to move to Guerneville and help establish an artists’ colony. In 1947, Frans joined them and they started the Pond Farm Workshops in 1949.

It would not last, however. The artists disbanded the workshops after three years. By 1952, Frans had left Pond Farm, accepting a new teaching position at the Rochester Institute of Technology and remarrying.7 At the age of 56, Marguerite had fled the Nazis twice, restarting her life and pottery workshop each time. She watched this new artistic endeavor dissolve with her marriage and was again faced with the challenge of reinventing herself.

Photo (possibly by Otto Hagel), courtesy of David Stone. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Teachings and Influence in America

Marguerite remained at Pond Farm, beginning her own summer sessions the very year the workshops disbanded. Her summer sessions encouraged rigorous discipline and absolute commitment from students, who lived in spartan housing and spent eight hours a day perfecting their craft. Her Bauhaus education influenced her approach, especially the apprentice-master relationship she found lacking in American art education. She strove to teach her students as individuals, as well as artists. She taught many students at Pond Farm, including influential potters Frances Senska, Hui Ka Kwong, Dean Schwarz, and Peter Deneen.“I came back, decided that here was my life, after all, and I would try it alone once more…. Slowly, I found myself again, and strengthened by the misery I had overcome, I felt that one had to face facts with courage.”8

“Excellence will never be a final destination, something that one has reached, and after which one can relax. No. It is a challenge renewed every day, and constantly elusive even to the best.”9

Through the decades Marguerite’s personal artistic philosophy grew and adapted. Still rooted in her Bauhaus teaching, she was inspired by her environment. She started using natural glazes echoing the browns, blues, and greens she saw in the landscape.

Photo by David Stone.

Photo by Leslie Carrow

Learn More

- Documentary | Pond Farm Pottery

- Wildenhain | The Marks Project

- Bauhaus: The School of Modernism — Google Arts & Culture

Citations

1 Wildenhain, Marguerite, The Invisible Core: A Potter’s Life and Thoughts, p. 17.

2 Ibid., p. 177.

3 “Bauhaus,” In Our Time: 25 Perspectives on the Visual Arts, Melvyn Bragg, BBC Radio 4, Nov. 2022, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m001dxtg.

4 Pond Farm Pottery National Historic Landmark Nomination (NHL), December 2023, p. 10.

5 NHL nomination, p. 16.

6 The Invisible Core, p. 35.

7 NHL nomination, p. 17.

8 The Invisible Core, pp. 96-97.

9 The Invisible Core, p.75.

10 NHL nomination, p. 18.

Last updated: January 17, 2025