Last updated: April 4, 2025

Article

Polio

FDR pays a visit to The Pines: West VA Foundation for Crippled Children, at Berkeley Springs, WV, May 12, 1935. Photo courtesy FDR Presidential Library and Museum.

Poliomyelitis, commonly known as polio, is an infectious disease caused by the poliovirus that attacks the central nervous system. Beginning around the 1840s, poliomyelitis began to be referred to as “infantile paralysis,” due to the belief that it primarily affected children. Between 1949 and 1954, children made up sixty-five percent of polio cases. Historians believe polio has been in existence for thousands of years. Although polio has a long history, the earliest written medical description of the virus was not recorded until 1789, when Michael Underwood M.D. in England, described patients who typically had a fever accompanied with a “debility of the lower extremities,” or paralysis of the lower body.1 Although only around one percent of infections result in paralytic poliomyelitis, paralysis continues to be the most well-known symptom of the virus.

The United States experienced its first documented polio epidemic in Vermont in 1894. The disease ultimately became a nationwide health crisis with further outbreaks in 1899, 1907, 1916 and 1949.2 Between outbreaks the number of cases would rise and fall with higher numbers during the summer and lower during the winter. In 1916 there were 27,363 cases of paralytic polio and 7,130 polio related deaths in the United States. The number of cases dropped substantially in 1917, and the U.S. would not see such high rates of infection again until 1948.

The poliovirus is spread via person-to-person contact, often due to unsanitary conditions resulting in contaminated food and water.3 Discrimination against people of color, the poor, and immigrants—people more likely to live in crowded cities—led to cultural beliefs that the poliovirus only affected these groups. However, children living in crowded areas with low sanitation were often exposed to the poliovirus early and developed immunity. As early as 1918, doctors realized isolated and rural areas—often believed to be “healthier” places to live—experienced more intense epidemics due to limited childhood immunity.4 This has been posited as a reason Franklin D. Roosevelt was susceptible to the poliovirus in adulthood, despite him not belonging to any of the categories that were discriminated against.5

Despite the number of cases fluctuating from year to year, the threat of polio outbreaks heavily impacted communities globally. In attempts to reduce infection rates, these outbreaks would result in the closure of swimming pools, movie theatres, places of worship, other public gathering places, and even schools. Some of the cultural impacts of the poliovirus include the revolution of medical philanthropy, the development of intensive care medicine, advancements in physical therapy including the development of equine assisted therapy, and the advancement of the modern disability rights movement, among others.6

Symptoms of poliomyelitis are similar to those of the flu; sore throat, fever, tiredness, nausea, headache, and stomach pain are common. Around 75 percent of cases are asymptomatic.7 The difficulty of distinguishing polio symptoms from the flu, and the prevalence of asymptomatic carriers, often contributed to its spread.8 A common misunderstanding about poliomyelitis is how long people are contagious. Despite the poliovirus only being able to spread up to six weeks after initial infection, many people were stigmatized long after this period and faced prejudice as they tried to re-enter public life.

There are three types of poliovirus that cause distinct forms of the disease—abortive poliomyelitis (a minor illness not affecting the central nervous system), nonparalytic poliomyelitis, and paralytic poliomyelitis. The well-known paralysis of paralytic polio occurs in less than one percent of cases, and most of these patients regain some if not all of their strength and mobility.9 Paralysis occurs when the virus destroys motor neurons in the central nervous system. In extreme cases of paralytic poliomyelitis, the paralysis caused respiratory collapse—a weakening of the chest muscles. In these cases, a patient was placed in a cylinder-shaped device called the iron lung, invented by Philip Drinker in 1928.10 Negative pressure inside the iron lung expanded the patients’ lungs and helped keep them breathing, providing the body an opportunity to rest and repair itself.

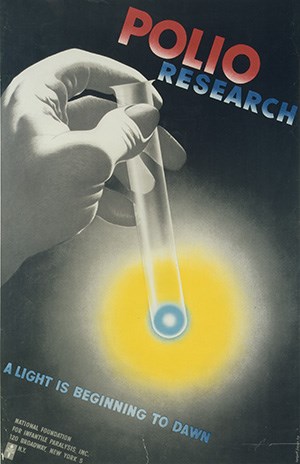

"Polio research a light is beginning to dawn" poster by Herbert Bayer for National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, 1949. Library of Congress.

A key development in the fight against polio occurred when Franklin D. Roosevelt, who became permanently paralyzed by polio in 1921, established the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis in 1938 to fund research for a vaccine (this foundation later became the March of Dimes). This foundation developed out of Roosevelt’s Georgia Warm Springs Foundation, which also operated an institution for post-polio rehabilitation. Roosevelt would not see the vaccine in his lifetime. Virologists Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin, both funded by Roosevelt’s foundation, developed polio vaccines in 1955 and 1961 respectively. The use of polio vaccines greatly decreased the number of polio cases globally, including the eradication of multiple strains of poliovirus.11 The poliovirus has been successfully controlled in the Western Hemisphere since the late 1980s. The Global Polio Eradication Initiative launched a global effort to immunize children throughout the world. Today, “wild” poliomyelitis—that is, poliovirus not spread due to vaccinations—is endemic only in certain countries in Africa and the Middle East.12 A vaccine-derived case of poliomyelitis resurfaced in 2022 in the United States with a confirmed case in New York.13 However, because of aggressive immunization campaigns world-wide, poliomyelitis is a preventable disease that can only circulate and evolve among large pockets of unvaccinated people.

Article revised on July 1, 2024

—Alice Creviston and Shelby Landmark, PhD

Notes

1 Underwood M (1789). "Debility of the lower extremities." A treatise on the diseases of children, with general directions for the management of infants from the birth (1789). Vol. 2. London: J. Mathews. pp. 88–91.

2 Bakalar, N. (2016). The unfolding of polio. The New York Times. The Unfolding of Polio - The New York Times (nytimes.com)

3 Polio (poliomyelitis). (2023). CDC. What is Polio? (cdc.gov)

4 Lavinder CH, Freeman AW, Frost WH (1918) Epidemiologic studies of poliomyelitis in New York City and the Northeastern United States during the year 1916. Public Health Bull 91

5 Tobin, James. The man he became: How FDR defied polio to win the presidency. Simon & Schuster, 2013.

6 Pincock S (2007). Elsevier (ed.). "Bjørn Aage Ibsen". The Lancet. 370 (9598): 1538. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61650-X. S2CID 54311450. Scott, N. (2005). Special Needs, Special Horses: A Guide to the Benefits of Therapeutic Riding. Practical guide series. University of North Texas Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-57441-190-4.

7 "Disease factsheet about poliomyelitis". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 26 March 2013

8 Wilson, D. J. (2005). Living with polio: The epidemic and its survivors. The University of Chicago Press.

9 Cuccurullo SJ (2004). Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Board Review. Demos Medical Publishing. ISBN 978-1-888799-45-3.

10 Gorham, J (1979). "A medical triumph: the iron lung." Respiratory Therapy. 9 (1): 71–73.

11 Two out of three wild poliovirus strains eradicated (who.int)

12 "Progress Toward Poliomyelitis Eradication – Afghanistan and Pakistan, January 2011 – August 2012". CDC.

13 Rai, A. et al. (2022). "Polio returns to the USA: An epidemiological alert." Annals of Medicine and Surgery, 82. DOI: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104563