Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Podcast 097: Applying Polymer Science in Conservation

North Dakota State University

Science of Art Conservation

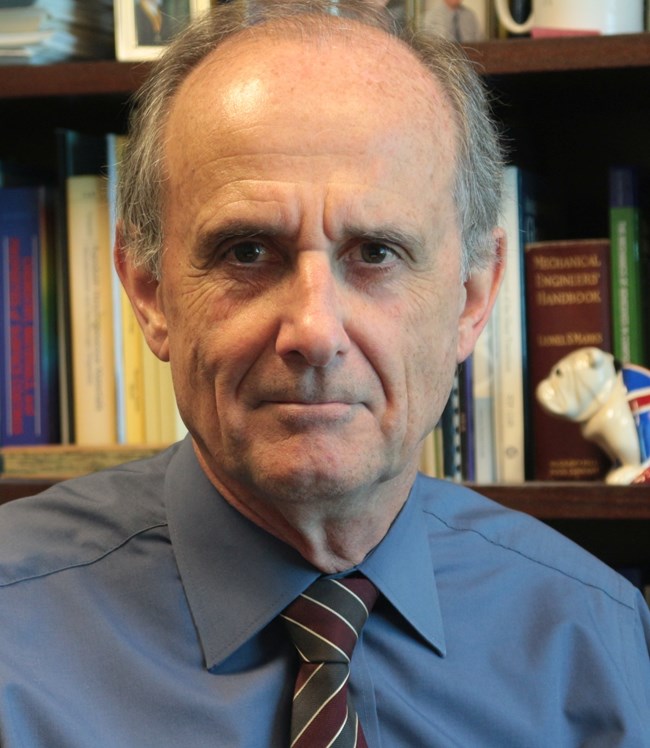

Alison Rohly: Dr. Croll, given your physics background, how did you first become interested in art conservation and how does your background in physics and polymers align with modern art conservation?

Stuart Croll: Well, firstly I have to say that I studied physics because that's the way my brain works. It seems to be what I'm probably best at in terms of the science and technology fields. There's probably no linear connection between physics and art conservation at all. And in terms of how my background applies, I liked and studied physics because I was always interested in how the world around me worked—that's the natural world as well as the technological world. Although I had to study it, I was never interested in nuclear particle physics or quantum theory or anything like that. I was much more interested in what I could see and how it worked and I suppose in that regard there was a natural sort of focus on material science and then polymer science became a natural part of that and coating sciences proved to be a natural part of that and a lot of artwork work is coatings and very similar materials.

Everything, my sort of scientific and interest inclinations, fit very well actually in many ways because a lot of the problems that appear are not only chemical related but they're sort of physics and engineering related too. I actually started my interest in art conservation and when I was about your age. I was at the National Research Council in Canada as my second job actually, ever. And I was studying the internal stresses generated in coatings where they try and kill us. That’s the evaporation of solvent and the cross-linking, densification, and all the rest of it and all these stresses tend to cause cracks and you see that they became brittle. And I published a handful of articles and then the Getty Museum got in contact with me and we exchanged letters in those days. And I ended up going down there. So I was in Canada, in Ontario, and I went down to the Getty.

It was only in the Villa in those days on Santa Monica Boulevard. No, on the Pacific Coast Highway in Santa Monica. And so I went in after hours, and I talked to their one technical person at the time, and he was interested in the work I'd done and why and how paintings cracked and how other works of art are cracking and what might have caused that and all the rest of it. And then he showed me around. I had my own personal tour of the museum and the backrooms where they looked at things and so on. So, and it made a huge impression on me at the time and so I was sucked in there and then.

Then, a few months later, a museum in England got hold of the same articles and we exchanged letters. I didn't actually go there, but… So I was fascinated to realize that there was this world where my research was relevant, that I'd never really thought of before. It's always nice to be appreciated, isn't it? I mean, it just sort of lay in the back of my mind for decades and then we were approached here actually, and that's how the interest here started. So Dr. Bierwagen and I were sitting there doing our booth duty at a paint show about 2002 and then two scientists approached us at the desk. One was from the Tate Gallery in London, England, and one was from the Getty museum in Los Angeles. And it ended up they wanted us to do some work.

Art Conservation Projects

Alison Rohly: So related to that, could you specifically talk about a project or two you've worked on as it relates to art conservation?

Stuart Croll: Well, I could talk about that one actually because it was all about modern art. Turns out modern art is now not so modern anymore. Many of the pieces we think of as modern art are actually 50, 60 or more years old and in need of fixing in some way. And most of my interests actually have been, most of my work has been, on what you would call modern art because of that. So, the project for us here was in two parts. One was to make latex that would correspond to the latex paint that the artists were using basically in the 1950s. So we found an old formulation and Dr. Webster's students made a latex. My part of it was to try to solve some mysteries that they were discovering, because these two places—the Tate in London and the Getty in Los Angeles—had started ramping up their analytical capabilities and so a lot of good spectroscopy and chromatography and they were looking at the materials in modern art, trying to understand what they'd got and how to fix them.

And they were finding all sorts of compounds in the modern paint that they'd never seen in old paintings. So my part of it was to go back—and this is where NDSU played its role because at NDSU in the library we've got all these old books that date from the start of the coatings industry as an industry. All the old books, they could take formulations, a lot of old journals and digests from the Ag. school here—they've all got old formulations and what sort of materials would have been in paint from the nineteen hundreds and then through the 1920s and 1940s and onwards. So my part was to try to look at the formulations of particularly the latex paint that would have been used by artists in the 1950s and 1960s, and deduce which were the most likely ingredients in those formulations.

So I spent months pouring through all the archives of NDSU and what they wanted as the final outcome was the top six most likely latexes, the top six most likely greater TiO2 pigments, the top six most likely surfactants, the top six and so on and so forth. Just to give them a clue as to A. what they would expect to find and get from their analysis and give them a clue as to perhaps where they could go and find more details so they could deal with their art problems with more confidence, I suppose, they were going to do the right thing.

National Park Service

Challenges in Art Conservation

Alison Rohly: What do you think are some major challenges in this field from a scientist's perspective?

Stuart Croll: Well, in many ways they suffer the same challenges that we do. So modern art really I suppose started perhaps between the World Wars and uncertainty boomed hugely after the Second World War. At the same time, the number of different polymers and coatings and plastics and other materials was booming as well.

So the artists had all these materials to try to get whatever effect they wanted to get and combine them in ways they what actually is would offend you and I with other aspects. Since, as I said, these works of art now in need of repair, restoration, conservation and understanding because although the artists might've used materials they bought at a local hardware store, most of the time they never recorded which materials they were. So in order to understand and fix them and so on, conservation scientists need to understand very exactly what the composition is of whatever it is, and why and how it's doing—progressing towards failure the way it is. So they need to be able to analyze the composition of a variety of materials in combination that you and I wouldn't think of, so they're interest in high end spectroscopy and chromatography and microscopy is profound these days.

You and I understand the interest and need for nondestructive testing. But you and I don't care if when we put an instrument on a surface it leaves a small mark. We don't really care, they do. So we must provide them with nondestructive testing techniques that don't touch at all, don't leave any trace of their use. And if we can't do that, art conservation scientists are allowed to take tiny, tiny samples from artworks. Well from places that the owners and viewers don't notice, but they have to deal with tiny, tiny quantities of sample. You and I might think were hard done by if we have to use only a few milligrams or something; I’m talking another order of magnitude or so smaller than that because the job is to do no harm to the artwork but still deal with all the issues.

There's this huge interest in analytical techniques—it’s one of the trends. There are a few labs around the world in partnership with museums and galleries and art conservation scientists, where they're using some seriously big analytical facilities. There are groups in Germany, France, and this country where they go and use the national labs’ synchrotrons to get high beam, high intensity beams, I would say x-rays or something, so they can examine a tiny, tiny samples and get all the information out to it. They can and that was unheard of a dozen, 15 years ago, but now I have such an interest in analytical techniques.

The NSF in this country gives grants for that sort of thing. Occasionally, not often, but occasionally. They have the same sort of interests that we would understand. I suppose in some ways you'd have to say it's slightly more extreme ways. One of the problems that modern materials have brought is fixing waterborne artwork, waterborne coatings, so did latex paint. You've got to be able to repair it in a way that doesn't change or damage the existing. We are intrinsically waterborne ourselves, so every time we touch it… so they have to learn compositions in materials they can use for filling in cracks and so on. They can then remove from a waterborne coating without damaging the original material.

Modern art, since the second World War, has had a lot of organic pigments available. Well, in the old days it was easy to tell whether this pigment was a cadmium based one or an iron based one, something like that. But now you've got all these pigments which are only slightly different one from the other and they're all the same carbons, hydrogens, oxygens and so on. Getting an exact match to the original color that the artist used, it's not trivial when you're faced with all the organic pigments that we know about now.

And in the old days, old masters' paintings were typically varnished, so you could disguise essentially the difference in gloss between the repair and the original material by just covering it was varnish which brought the gloss across the whole thing to the same value as well. If you're trying to touch up, say, a big metal sculpture where there's a bit of rust or something's happened in one corner, you've got to not only get the color exactly right, but you’ve got to get the gloss exactly right. So we have to match gloss as well as match the colors. So this is lots of things to think about.

North Dakota State University

Bronze Art & Architectural Conservation

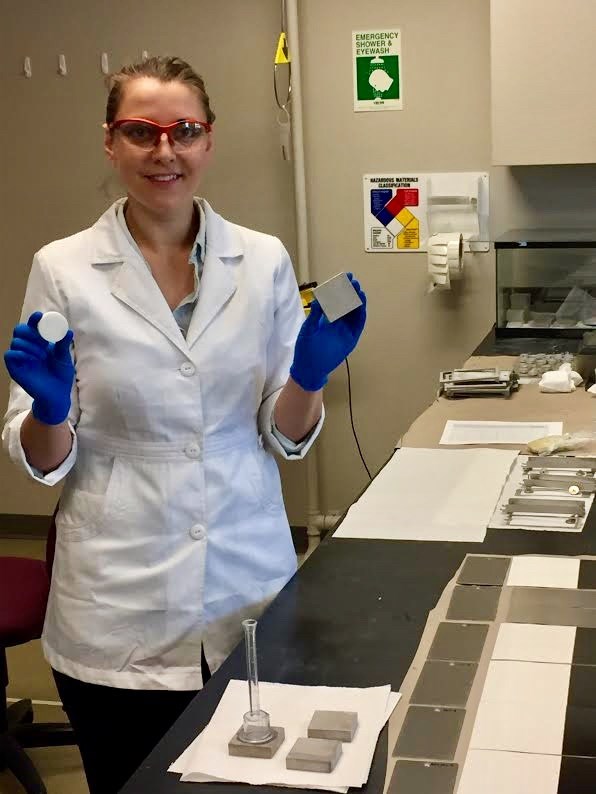

Alison Rohly: Dr Battocchi, how did you first become interested in bronze art and architectural conservation and how does your background in materials and coatings help with your approach to conservation?

Dante Battocchi: My interest in conservation comes from a long time ago when I was a friend with a student who was developing a polymer under a grant from NCPTT; she was an artist and a chemist and so she was developing a selectively removable polymer to be used in art conservation. I was doing another project, but we are very good friends and so I kept learning and listening about what she was doing and got an interest in this bronze art conservation field. And when it was time that I decided to open a small business, Elinor Specialty Coatings, and we were deciding what to produce and what to develop as a product, we decided to go with that particular polymer. We licensed it from NDSU and we developed it into a commercial product. So I'm still in contact with Tara and I keep her informed of what her polymer is becoming. And I discuss pretty regularly with the NCPTT on what's going on and stuff like that.

It's two fold. A friendship and also the commercial opportunity. I am a jack of all trades in materials. I have a couple specific interests, but I pride myself that I can approach different people in different areas. And so conservation, especially metal conservation, has a lot of little aspects. I think that my background helps me to tailor my solutions or my discussions to the specific problem. Conservators have very, very wide, broad interests. Sometimes I think it's good to be a little more of a generalist to understand what they need and what they are looking for.

Bronze Art Conservation Projects

Alison Rohly: Excellent. So could you specifically talk about a project or two related to bronze art protection?

Dante Battocchi: Yes. One of them that we hope is going to give us good visibility is that we provided the product that is called Bronze Shield, based on this polymer that was developed here at NDSU, to a conservation company that applied it to the Arthur Ashe statue at Flushing Meadows in New York. Flushing Meadows is where the US Open of tennis are played. We hope that that is going to be our showpiece to show that the material actually works, and it really does the job.

The second one, my first approach was that I've been invited once to a conservation site and there was a very big statue from the 1800s of the general on a horse. And so I worked with the conservator to clean it and to take out the old coating that we didn't really know what it was. We re-did the patina and we applied a clear coat and then the wax. That one was my first approach to see how conservators worked and how deep they work; even on a big piece of metal it needs to be because the surface needs to be accurately cleaned and worked inch by inch. So I like that.

Alison Rohly: Excellent. And that's sort of where the Bronze Shield developed was initially from the company that you started and now it's being applied currently to various statues and sights.

Dante Battocchi: Yes, we have been in communication with a lot of conservators in the past few years. A few of them and knew about the work at NDSU and now they all know the product from the commercial side. And so we have been giving and selling it to conservators for their projects, mostly for private conservation projects but also for municipalities and stuff like that. So for public art.

Challenges in Bronze Art Conservation

Alison Rohly: So from your perspective, what are some of the most relevant challenges today with specifically bronze art conservation?

Dante Battocchi: Just to take a general approach. I think that every conservator has a personal approach to what product or what solution needs to be applied to the particular [object], so it's kind of a difficult endeavor to give a product and have them test it, because testing takes a lot of time and everybody wants to give it a little of a personal touch. Another way is that there are lots of bronzes that are out in the field, they have old conservations on, so that is a very difficult way to de-paint or to strip the paint on, especially if there are not too many records available for that. Some staff just have more records on previous work than others.

With my commercial hat, one very difficult thing to do is that when we give out the product for testing, it is very difficult to get feedback back. I don't know if that one is a question off the length of the test or because when one project is done it is out of sight and out of mind. But having that feedback will be very important to know if the product or the polymer or the solution needs to be further developed or if it's okay like that. It's challenging on the scientific side to keep the surface protected, but with the ability to remove whatever coating we put on for the future removal, but also, on the product side, it would be good to know if it's working or not in the current time to see if we need to modify something or not.

Alison Rohly: Excellent. Well, thank you so much for taking the time today to talk about your research with us and conservation.

Dante Battocchi: Thank you very much for giving me the opportunity.

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.