Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Podcast 092: Creating Coast Salish Imprints: The Public Art of Susan Point

Jeff Cannell, Archives of Coast Salish Arts

Susan Point, Salish Artist

Robert Watt: My first hope was to produce a book that would be a celebration of the public work of a very great artist.

I said several years ago, if we were in Japan, Susan Point would be termed a national treasure. And that's how I think of her.

And so doing this book, I think gives many more people that chance to appreciate the dramatic scale of her accomplishments.

I think it also helps to ensure something that is so important to her and that is the business of a Coast Salish aesthetic and cultural imprint in this part of the world.

I quite often meet people who, if the discussion turns to First Nations art they immediately talk about totem poles.

Well, totem poles were never part of Coast Salish culture.

Carved house posts—typically more internal elements in a big house than external elements—but certainly totem poles were not a part.

And the styling of Coast Salish pieces is very distinctive.

And my hope is that people who have a chance to read this will come away with that understanding. They will understand that the people here, the First Nations here, had their own aesthetic, their own style. I think through her art, Susan has succeeded in achieving that.

Jeff Cannell, Archives of Coast Salish Arts

Spindle Whorl

Catherine Cooper: The spindle whorl seems to be a very important motif. Could you tell us a bit about why?

Robert Watt: I think that's a question maybe best answered by Susan herself.

Early in her researches she discovered and admired the historic spindle whorls in various museum collections and she was inspired by them.

She created new designs using the form.

And of course the circular form as you know for First Nations cultures, not only in this part of the world but in many other parts of the world.

The circle of life and the way it allows you to talk about the importance of four: four seasons, four elements, all those things.

Kenji Nagai

Exploring Different Media

Catherine Cooper: One of the things that sort of struck me with the number of materials she's worked with is it's always: if it's new and she can learn, that also seems to be a bit of a theme.

Robert Watt: Oh yes.

Yeah. She's been a pioneer in using so many different materials, far more materials I think than any other First Nations artist.

Certainly in our area and perhaps right across Canada.

I can't bring to mind any other First Nations artists that has so dramatically and aggressively explored different media.

One minute it's metal and the next minute it's cast concrete and the way that she locates associates and mentors to teach her new techniques and then also people that she can work with to bring her ideas fully to life.

Stained Glass, Christ Church Cathedral, Vancouver

So for example, the great stained glass window—art glass window in Christ Church Cathedral in Vancouver involved a very close working relationship between a glass artisan, Yves Trudeau, and Susan, who did the design and adjusted the design.

Kenji Nagai

But at one point she went to Seattle with Yves Trudeau.

When the design had been completed and accepted by the cathedral people she went to Seattle with Trudeau to work with the glass blowers and I think it was Fremont Glass in Seattle.

And she was there for days with Trudeau, being involved with the process, watching the glassblowers produce the sheets of glass in a range of colors.

That’s been part of, an element of, her career right from the start: working with skilled artisans, in various fields to enable her to produce something in a medium that she wouldn't be able to do if she was working solely by herself.

In that process of collaboration, she's always front and center.

She's always watching and she knows how she wants something to look at the end.

And she's very patient and is always ready to go back at something to achieve a particular result. And she's a real perfectionist and very meticulous. She doesn't stop until she's satisfied that no other result is going to be possible.

Robert Watt

Centered Around Stories of People and Place

I think another part is, and this really struck me, was when she received a commission, one of the first things that she did was to take a very close look at where the work was going to be and what kind of relationship it might have with the building or the landscape that it was going to be part of.

So her initial research was into the Coast Salish aesthetic.

Later researches, piece by piece, were centered around the stories and the history of the places where the work was going to go.

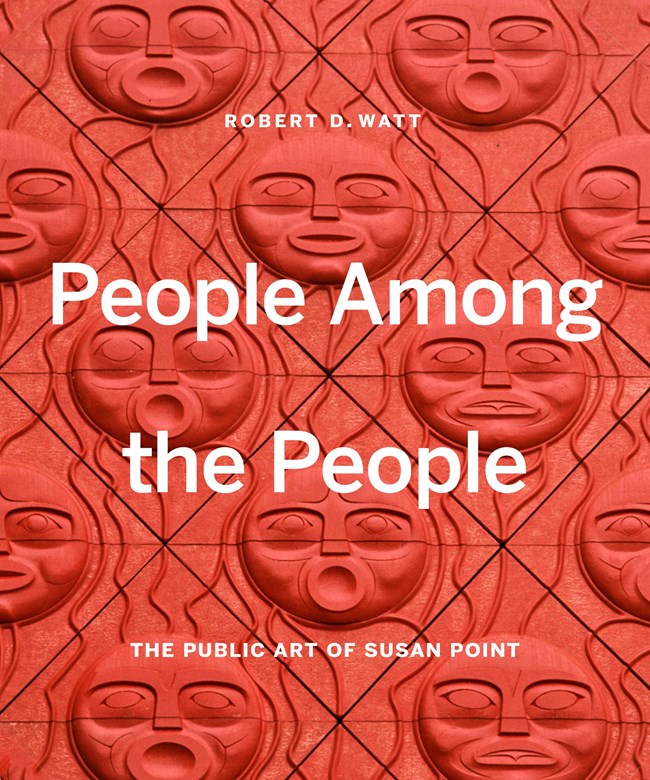

So for example, the dust cover of the book shows the four corners piece, which is on the wall of one of the larger buildings at North Seattle College.

And the coloring, and some of the framing elements in that design, relate directly to a stream and a particular red earth color that was important for the First Nations people who lived in that part of what is now North Seattle.

And that sort of care and attention is very, very characteristic of all her work.

Kenji Nagai, Archives of Coast Salish Arts

Resurgence of Coast Salish Art?

Catherine Cooper: So you've known Susan for many years and watched a lot of this work come about. Have you also seen a resurgence of Coast Salish art since she started?

Robert Watt: I've become aware of it and I remember being on Vancouver Island and visiting friends North of Victoria in Saanichton and I went to do some shopping at a small shopping center or mall, and there were some beautiful carved pieces forming part of the entrance way in one of the larger stores there.

And I could see right away that they were Salish because I saw the elements that I had come to understand as Salish through Susan's work.

And then I found a label identifying them as the work of one of the Marston brothers; and the Marstons, and a number of other young artists, are now all working in using Salish aesthetics and so their work is quite distinctive.

And I think Susan has been at the vanguard of a resurgence, or a Renaissance basically, in Coast Salish work.

Halkomelem Language of the Musqueam

Catherine Cooper: One of the other things that has seemed incredibly deliberate and important about the way you constructed the book is the inclusion of her native dialect.

Robert Watt: Yes. And that was a suggestion that was made to me by the main editor that I worked with: Mike Leyne of Figure 1.

And it was wonderful to work with him.

He's a consummate professional and he made a number of suggestions to me too, that I think were particularly important in giving the book it's final appearance and impact.

And one was his suggestion to organize the pieces rather than chronologically, which was my thought as an historian, to organize it geographically beginning in effect on the Musqueam lands then going out from there in a series of circles.

And taking this geographic look, almost like a giant spindle whorl in a way, reaching out from Musqueam to, in the end, places quite distant.

But his other big suggestion was, he said, Is there not an opportunity here to introduce people to Halkomelem, the traditional language of the Musqueam, the downriver dialect?

And I thought it was a great idea. And he said, well, how can we do that? So I first discussed it with Susan, who was enthusiastic and then with… I was very, very fortunate to be able to enlist the help of elder Larry Grant of the Musqueam people, who is head of their language program.

So Mike and I together settled on the words that we hoped to integrate into the text and then worked with elder Larry Grant to receive the correct Halkomelem word.

And we also had similar help from Dr. Barbara Brotherton, who is the curator of Native American art at the Seattle Art Museum.

And she was very, very helpful in, in effect, doing the matching sort of thing.

But for the First Peoples of what is now Washington state.

Catherine Cooper: And the pronunciation guide in the back is incredibly helpful.

Robert Watt: Yeah. And that was there with the approval and support of Larry Grant who got the agreement of the Musqueam people that it could appear there.

Because it's something created originally for the language program at Musqueam and in effect directly borrowed from their printed resources.

King County Metro Transit Archives

Preservation and Education

Catherine Cooper: Do you view this book as an effort at preservation and education?

Robert Watt: Yes. A very good question. And yes, I do.

Maybe one way of underlining that is, delightfully, Susan's work as an artist continues and as we speak, she is working on a number of large new commissions.

And so the book is a portrait in time. It begins, the earliest work is 1981-82 and the most recent is 2017. And as the decades unfold, it may will be that one or two of the pieces succumb to the elements.

Nobody wants that to happen, obviously, beginning with Susan, but you know, she's nothing if not a realist.

So as you see with the bus shelter piece in Seattle, that's the one in the book that no longer can be seen because it was painted on plywood and it inevitably, because it was open to all the winds that blow in downtown Seattle and the rains that fall, and the sun beats down, it ultimately had to be retired.

I think the book is a very important record of really, really important work by a very great artist.

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.