Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Podcast 089: Conserving Captain America: Using Klucel M on Comic Books at the Library of Congress

Claire Dekle, Library of Congress, Conservation Division

Joint Project

Cathie Magee: Well we did the project as interns at the Library of Congress. We were both there as third year graduate fellows. It’s a part of our graduate education to do a third year externship for our conversation degrees. We had both gone to the Library of Congress. I was in the rare book lab and Michiko was in the paper lab. This was kind of a joint project between labs, which happens sometimes. It was the curator who approached conservation?

Michiko Adachi: Well the supervisor, Claire Dekle, who’s a senior book conservator; I think she thought it was a good joint project to do for us. That’s how she brought it to us. It originally came from the serials division who takes care of the comic books at the Library of Congress.

Cathie Magee: Library of Congress has thousands. How many hundreds of thousands?

Claire Dekle, Library of Congress, Conservation Division

Pilot Project to Develop Protocol

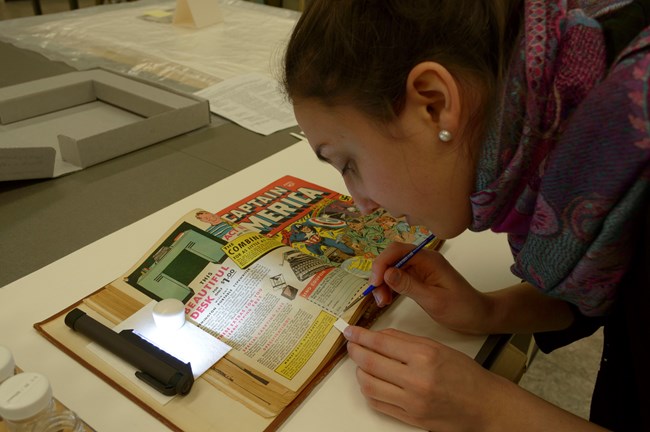

Cathie Magee: This was kind of a pilot project for the lab in a way. One of their hopes for us was to have us develop a sort of protocol for addressing the materials. Most of the comic books are printed on newsprint, which is extremely acidic. I think most people know it doesn’t age well at all. They can be quite fiddly to repair. Some of the challenges are getting tide lines in the paper.

If you use an adhesive that has a lot of water in it, if it dries, you end up with these visible rings of degradation products that form around where the water was. That’s an aesthetic that we want to avoid. We don’t want to cause those. Then the other challenge is just, handling the paper can be extremely delicate. Newsprint as it ages tends to start cracking and then flaking and little pieces will just break off. They are a real challenge to conserve, which is probably one of the reasons why not many of them came to the Library.

Michiko Adachi: Also, the important thing is that the treatment has to be streamlined because there are multiple pages in each comic book. That was also an important factor to consider.

Claire Dekle, Library of Congress, Conservation Division

Careful Disassembly

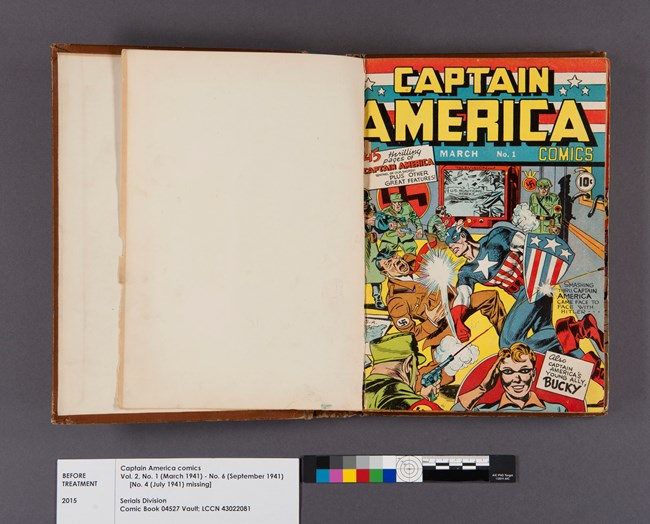

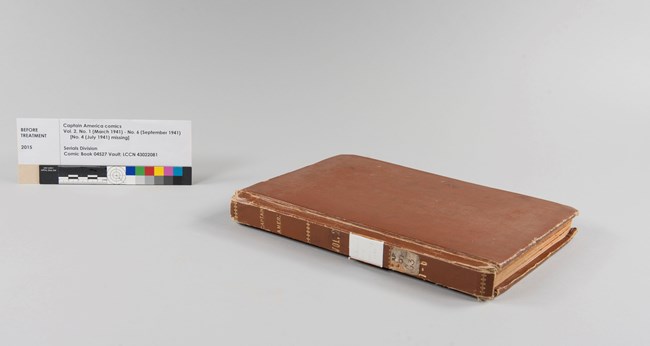

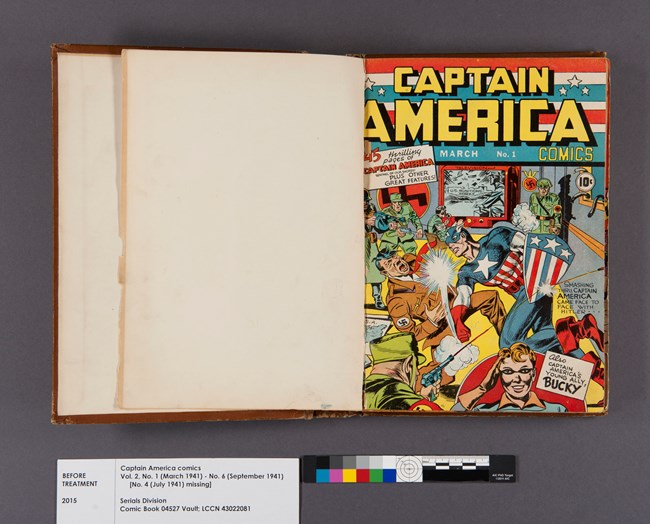

Cathie Magee: They end up being very time consuming because they’re 64 pages in a comic book. The project that we were given were six comic books. They were the first six printed Captain America comic books from 1941. It’s not the original art, it’s just the printed comic books. They had been stapled together through the spine. Each comic book has its own section of newsprint stapled through the fold.

Then those six books had been stapled through the spine with these big, heavy duty staples. I think there were 10 of them. Then that sort of makeshift text block was glued into a case binding. It’s a really common library style binding that’s cloth covered. It was really only bound with adhesive. Getting that off was fairly easy, because it was practically falling off because of the glue had decomposed.

Getting the comic books apart was one of the first steps. One of our supervisors, Claire Dekle, did that part by gently lifting the legs of the staples. She kind of sawed them off because we didn’t want to just lift the comic books up because we really feared we would continue to damage them. Then once they were apart, we could really see that the staples had obviously caused a lot of perforations in the spine.

Cathie Magee, Library of Congress, Conservation Division

Safe Handling, Publicly Accessible

Michiko Adachi: You couldn’t open the comic book from its natural binding because of the staples.

Cathie Magee: That’s why we had just found them in the first place. We should backtrack a little and say that the intention of this project was to treat these as research materials. They’re obviously not circulating, but they are requested by researchers really frequently to be viewed. The researchers get to sit in the reading rooms and leaf through the comic books.

They could not do that with these books in this state, because the paper was very fragile and the binding, these six things stapled together, it couldn’t open wide enough to be read fully. We really feared that if somebody tried to force it open, they’d end up causing a lot of damage. The curator really wanted these in a state where they could be handled safely by researchers.

Michiko Adachi: Also, because it’s the Library of Congress. It does have to be accessible to the public. That’s also important.

Cathie Magee: It is their mission.

Jason Church: Do you know the history of those bindings?

Cathie Magee: No. I don’t think we ever knew who did that. I don’t think it was believed that that happened at Library of Congress. Elsie has been known to rebind things in library bindings and lots of libraries do that, where the books are meant to be more functional than art pieces.

Michiko Adachi: I believe most comic books are stored the way they come in.

Cathie Magee: Yeah. That happens in conservation. You end up discovering some work someone else did, and you have no idea who, but you’re silently cursing them, whoever they are.

Jason Church: Once you got the bindings apart, what was the treatment for the individual comic books?

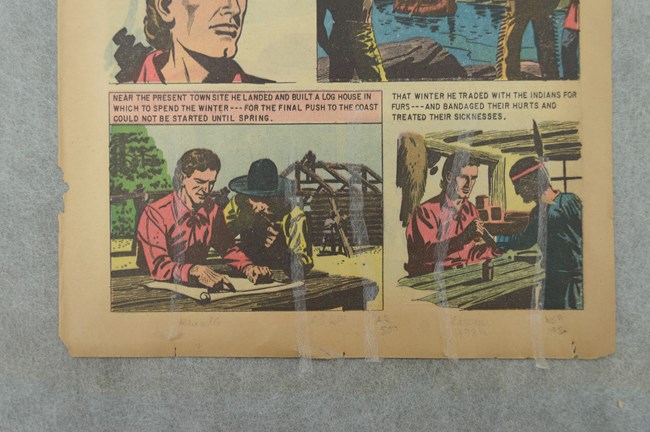

Michiko Adachi: The papers exhibited a lot of tears, losses. We weren’t gonna fill the losses, because that would have been too time consuming and visually just bridging it would have been enough. It was mostly mending the tears so that they could be handled again.

Cathie Magee: We’d call it stabilization.

Michiko Adachi: Yes.

Cathie Magee: Rather than aesthetic compensation.

Michiko Adachi: Yes.

Cathie Magee, Library of Congress, Conservation Division

Testing Numerous Approaches

Cathie Magee: For that we used a solvent reactivated tissue that Michiko and I developed. That was our main role in this development of the protocol for treating these things. I mentioned the tide lines and Claire Dekle had done some testing on the inks and discovered that some of them were soluble in or sensitive to water or ethanol. We didn’t want to just put down wheat starch pastements.

We didn’t want to use a paper that was too thick because that obscures the media. We need these to be legible. We also needed something that would flex. We had to find the right adhesive. We have a standard set of adhesives that are pretty common in almost every paper lab. We can give you a list of those. That includes the wheat starch paste and methylcellulose and some other things, synthetic adhesives.

We tried a number of those. Library of Congress conservation makes its own repair tissues ahead of time, just in bulk, because we go through them so much. We had tried some of those with different adhesives. They just didn’t work the way we wanted them to. They were a little too opaque, and a lot of them were too stiff. They popped off when the paper was flexed. I should also mention that we …

Michiko Adachi: The adhesion strength wasn’t that great.

Cathie Magee: Yes, that’s the reason. To do all of this testing, we were given a discarded comic book from the serials division at LC. It was artificially aged by the preservation and research …

Michiko Adachi: Testing.

Michiko Adashi, Library of Congress, Conservation Division

Klucel M

Cathie Magee: … testing division. Yes, thank you. It was from 1956, so it was a little bit later. They put it in the aging oven for a while to get the paper to a state that was closer to Captain America. Then we used that to do all of our testing. We have this lovely image of these different strips all laid out with the different adhesives. We had settled on one particular kind of paper just to knock one variable out. It’s a paper that we’re familiar with. It’s a machine made Japanese paper. It’s very thin. We were comfortable using that.

Then we were experimenting with these adhesives, and then reactivating those adhesives with different solvents. After a few test runs, we decided that what we were using wasn’t working. Sylvia had this idea to try Klucel M. Sylvia Albro, who’s the senior paper conservator at LC. She had gotten a little baggy for us and we made some up. It’s something I had used previously at the Walters Art Museum, where I am now. I was like, “Oh yeah, that’s a good idea.”

Michiko Adachi: I think Klucel G is a common adhesive used in book and paper conservation, but there is a paper out by Feller that Klucel M yellows a little bit more. I think maybe that is why people have shied away from M, but because of the higher molecular weight, higher tact, we thought we would give it a shot. We did like Klusel G. It was just the adhesion wasn’t strong enough.

Cathie Magee: It was nice and opaque compared to the other.

Michiko Adachi: Nice and transparent.

Cathie Magee: I’m sorry. Thank you. It was nice and transparent compared to the other adhesives, which were a little more opaque. We made up a new set of testing papers. It’s a simple process to make this stuff. You just paste it out and lay on your paper and it’s done.

Michiko Adachi: Yeah, we found that Klucel M worked.

Claire Dekle, Library of Congress, Conservation Division

Toning Repairs

Cathie Magee: Yes, it worked brilliantly with ethanol, which was wonderful for us because that really minimized the tide line formation. Really, it was just wherever there were two inks printed on top of each other, like green is yellow over blue or something.

Michiko Adachi: Was sensitive to ethanol and the latter. The other inks weren’t sensitive to ethanol. That was the solvent we decided on using.

Cathie Magee: We did end up toning the mends with acrylic. We had a spray booth in Library of Congress, and we have an airbrush. We could airbrush our acrylic paint mixtures onto the paper to tone them first. I think that kind of gave that thin paper a little bit of extra structural integrity because it’s so thin. Klucel M is really viscous. We were only using a 2% solution. It’s really quite thick.

Michiko Adachi: And because the paper was white, toning really helped to integrate the mend into the medium.

Cathie Magee: Exactly. We could put it over that colored printed material and you can barely see it. It’s really fantastic. I was delighted how well it worked.

Jason Church: Once the pages were mended, what was next for the comic books?

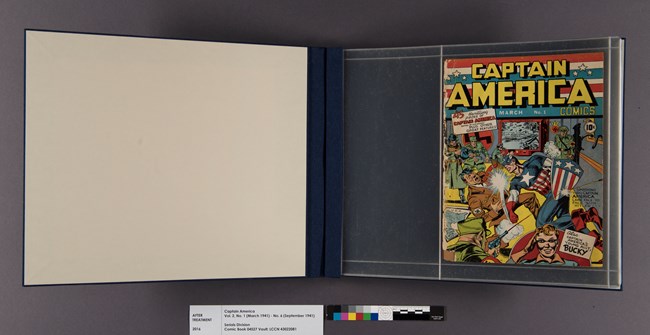

Michiko Adachi: Because it needed to be handled, the decision was made that each sheet would be encapsulated in a polyester film. It won’t be in its original form. It will look a little bit different, but that is the decision that was made. We had to encapsulate each sheet. We actually had to make the mylar encapsulation too.

Cathie Magee: We did. This is high quality. These were custom cut, by us, by hand.

Michiko Adachi: Welded with an electro-, what, oh no, ultrasonic welder.

Cathie Magee: The ultrasonic welder, made by Bill Mentor himself. We did have to cut the comic books down the center fold, which is a step beyond dis-binding.

Michiko Adachi: It’s that the ideal, but if we kept it in a bi-folio form, you wouldn’t have been able to read it in the right order in this binding.

Cathie Magee: Yes. Okay. Let me clarify that. If we had left the comic books stapled together through the center fold, that fold would have eventually failed. I guarantee it because the paper was just so fragile. It had started to tear along that folder anyway. It was really only a matter of time. You can go back and mend those any number of times, but then you risk in doing a lot of damage to the newsprint.

We had observed that this newsprint was so fragile, that if it flexed at all, it really risked exacerbating the existing tears. We really needed to keep them flat. In order to do that, each page was separated from its conjoin and then it was encapsulated between two sheets of Melanex that was much, much wider than the … It’s smaller than eight and a half by eleven, but it ends up the finished book has a margin of 11 centimeters. That’s where the pages flex.

You can turn each page without actually bending the page. You’re bending the Melanex as you flip the page. Then the rigidity of the Melanex really supports the comic book page. These can be accessed really, really easily by researchers. They do have to wear cotton gloves, but that’s to prevent getting fingerprints on the Melanex, which is nice. It’s got a nice margin around each page too, so they have space to grip the Melanex without actually even getting a finger on the, on the newsprint.

Jason Church: How will this be rebound?

Claire Dekle, Library of Congress, Conservation Division

Binding Each Issue

Cathie Magee: Each individual issue was given its own binding. We call it a scrapbook style binding. We took this stack of newsprint pages in Melanex and actually, we stack them and clamp them and then drilled holes with a drill to create sewing holes. We used a linen thread to sew them together. A lot of people do it with posts, with metal posts, like regular scrapbooks. These were actually a little too thin for that. We had to improvise and use linen thread. We made covers out of laminated binders board and covered them in a lovely blue cloth that the curator picked out, because she thought it was appropriate.

Michiko Adachi: For Captain America.

Cathie Magee: Yes. We made our own labels and we bound each one in a big scrapbook. One of the trade-offs is that it’s gone from being this little tiny book object to six, big, hefty scrapbooks. The storage space has gone from this to this, which is something to consider when this kind of treatment is proposed for future objects.

Jason Church: Is this extreme treatment because of the extreme condition that these first six Caps were, or is this something you foresee for other comics in the collection?

Michiko Adachi: I think it was because it was an exceptional … Yeah, the extreme condition, because it was just so deteriorated. The paper was just so brittle.

Cathie Magee: I think this is something that we would avoid if we could, and maybe it would depend on a case by case basis if something was really popular but in bad condition, then this is the route they would ask us to go.

Jason Church: I know you said that these were frequently requested. Do you think the recent popularity of Captain America may have led to this treatment as well?

Michiko Adachi: Yeah, I would assume so.

Cathie Magee: That seems entirely likely. Yeah. These books are available to anyone who requests them.

Michiko Adachi: Yes, yes, again, because the Library of Congress is a public library.

Cathie Magee: Yes. Government institutions.

Michiko Adachi: Yes, it has to be accessible to everyone really.

Jason Church: Very important question. While you’re doing all this work, did you read them?

Cathie Magee: Some of them.

Michiko Adachi: Yes.

Cathie Magee: We have a lot of great pictures of Hitler getting punched in the face.

Jason Church: Yes.

Cathie Magee: I am not a comic book fan, so it was a surprise for me to realize that there’s the Captain America story and then there’s all these other characters that I have never-

Michiko Adachi: Yeah, Caveman and Tuk.

Cathie Magee: It’s a very 1941 cultural aesthetic that was eyebrow raising from a 21st century perspective.

Michiko Adachi: It was interesting. I didn’t know Captain America’s shield wasn’t round.

Cathie Magee: Oh yeah. It started out as not round.

Jason Church: Until later.

Cathie Magee: No, it’s like by issue three or something. It’s a round …

Michiko Adachi: It was interesting to see how he was depicted. Some of the volumes his jaw is more angular, like strong, whereas some of them are softer.

Cathie Magee: There’s that one issue where he disguises himself as a woman.

Michiko Adachi: Oh, that must have been yours.

Cathie Magee: That was one of mine, yeah.

Michiko Adachi: Yeah, it was funny. He had eyebrows over his masks.

Cathie Magee: Really? I hadn’t noticed that.

Michiko Adachi: That’s how they depicted it.

Treatments, Testing, Approaches

Cathie Magee: Yeah. We should also mention that, there were six issues. Michiko and I each treated two. Then one each was treated by Claire and Sylvia. We were constantly consulting with them on our work, and the direction we were going. What was too much? Where should we draw the line in terms of mending? Then ultimately what the goals were from this mending material.

I should also mention that the reason we presented this poster at this conference, which theme is innovation and treatment is that not a lot of people will use Klucel M because of the study that Michiko mentioned. But the PRTD lab at LC is doing more research on that adhesive, and we included some of that in our poster, but they’re going to continue that, to investigate the degradation qualities of Klucel M. It’ll be really interesting to see what they find and maybe more people will start using this stuff as a result.

Jason Church: You said this was an internship. Where are you headed or where are you at now?

Cathie Magee: I’m at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, working on medieval books.

Michiko Adachi: I am a fellow at the MFA Boston, in the Asian conservation studio.

Jason Church: Well hopefully we can talk to each of you at a those locations on projects you’re doing in the future.

Cathie Magee: Yeah.

Michiko Adachi: Yeah.

Jason Church: Thank you very much for talking with us.

Michiko Adachi: Thank you.

Cathie Magee: Thank you.

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.